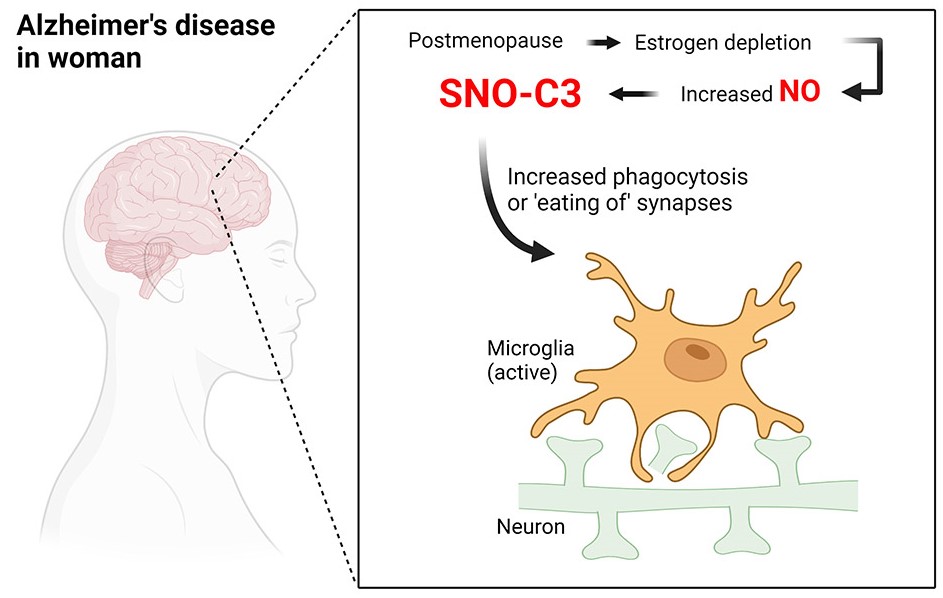

The higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease in women compared to men may be due to a difference between the sexes that manifests as a protein shift in the brain. Specifically, it is found that C3 protein changes occur more often in female dementia patients than in male ones. This immune protein leads to synaptic atrophy when it undergoes a change. Proteins adapt to their new environment in part because estrogen levels diminish after menopause.

Nearly 4 million women are among the more than 6 million Americans aged 65 and over who have Alzheimer’s disease. About twice as many females as males are afflicted. Nobody knows for sure what causes this neurological illness. The usual plaques in the brain are known to be formed by misfolded amyloid beta proteins. Moreover, tau protein filaments, or fibrils, develop inside the nerve cells. Both are known to increase the risk of brain cell death and subsequent cognitive decline. However, additional systems that are poorly known seem to be implicated in the illness as well.

Post-translational changes

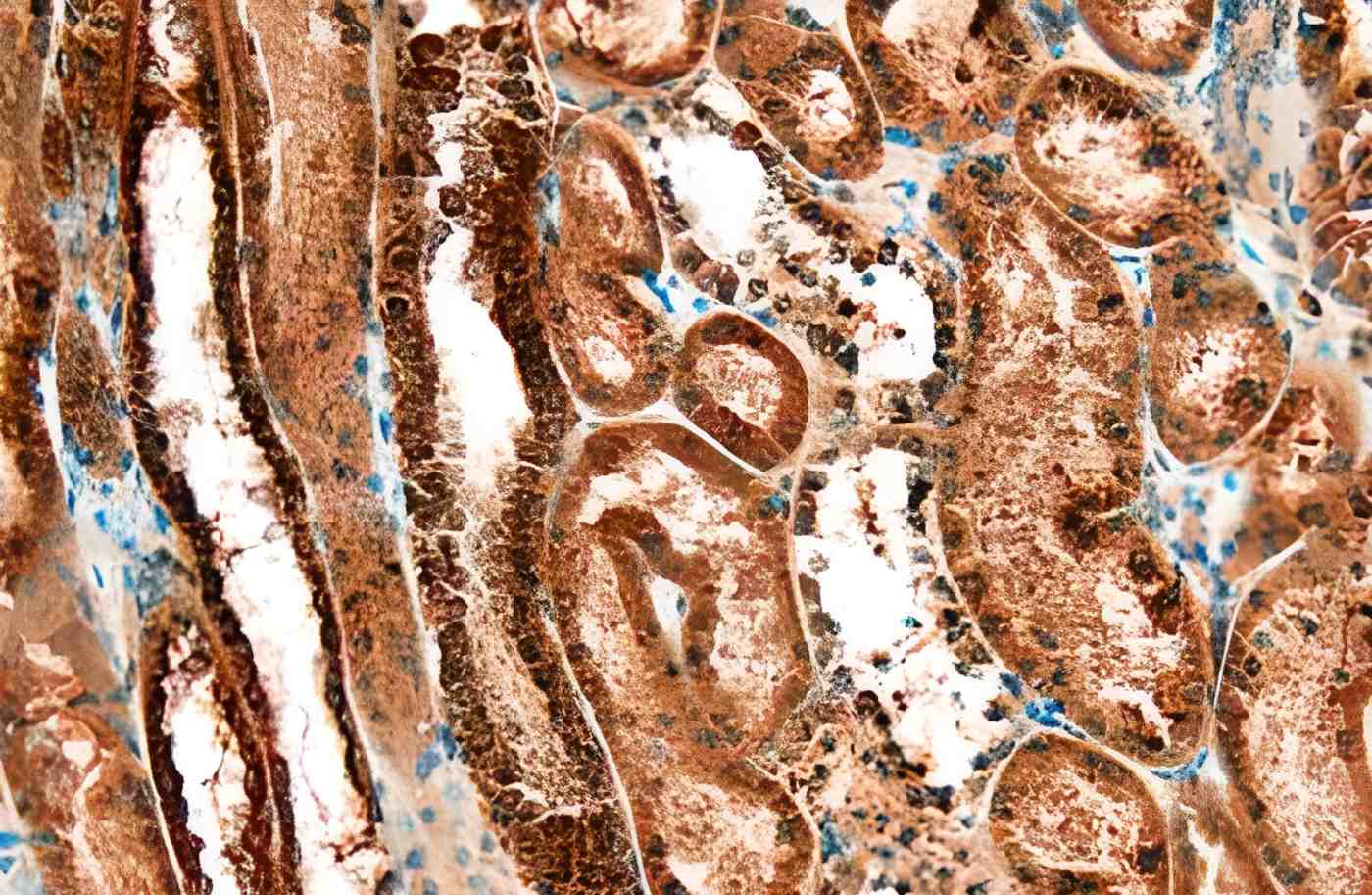

Researchers from China’s Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, led by Hongmei Yang, have shifted their focus to other processes that may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease. Post-translational changes were investigated by the team studying the human brain. These are protein extensions that can change how the protein works.

S-nitrosylation (SNO) is one example of such a change. In this situation, a nitric oxide group serves as the appendage. The potential involvement of this alteration in neurodegenerative illnesses was suggested by previous research. Yang and his colleagues looked into the brains of 10 men and women who had died with and without Alzheimer’s disease to see whether there were any differences between the two groups.

Distinct variations

Researchers found a total of 1,450 SNO-modified proteins across all human brain tissues. Despite the fact that Alzheimer’s brains had just slightly more SNO proteins, their composition was very different from brains without Alzheimer’s. They utilized statistical techniques to figure out which proteins were more likely to be S-nitrosylated in Alzheimer’s brains.

The researchers used this information to create a ranking of proteins that may have a role in Alzheimer’s disease. They discovered alterations in proteins associated with autophagy, a cellular mechanism that eliminates unnecessary or broken pieces. This finding has the potential to shed light on previously unrecognized mechanisms through which Alzheimer’s progresses.

The majority of these alterations concern females

The so-called complement factor C3, a protein with a crucial function in the innate immune system, showed the most dramatic modifications. The investigation revealed that altered C3 proteins were mostly found in the brains of females with Alzheimer’s disease. Female brains with Alzheimer’s disease exhibited a 34-fold increase in SNO-C3 compared to the brains of women without Alzheimer’s disease. Male Alzheimer’s brains increased just 5.6-fold.

Although C3 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, its S-nitrosylation and differential distribution between the sexes were previously unknown. Scientists used human stem cells to show that the altered C3 proteins increase neuronal deterioration by leading immune cells to erroneously attack healthy synapses.

Beta-estradiol could shield premenopausal women

The data demonstrated that beta-estradiol, a female sex hormone, may inhibit C3 modification, a process critical to the proper functioning of the immune system. This may explain why postmenopausal women have a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s than men do. The findings imply that beta-estradiol could shield premenopausal women against S-nitrosylation of C3.

However, this defense diminishes when estrogen levels decline after menopause. Therefore, C3 proteins in women’s brains undergo greater pathogenic alteration, making women more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. Together, these discoveries improve our capacity to comprehend Alzheimer’s disease’s progression and, maybe, to design more effective strategies for early diagnosis and treatment.