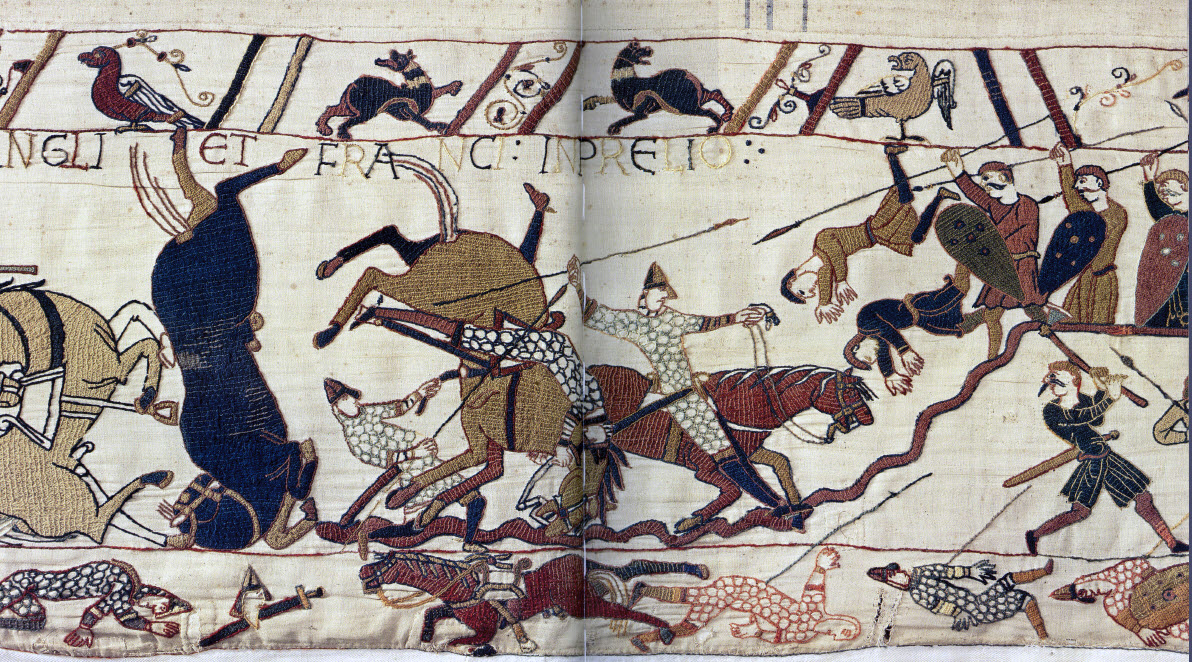

After his victory at the Battle of Hastings on September 28, 1066, William the Conqueror (1027-1087), the most renowned of the Dukes of Normandy, was crowned King of England. On Christmas Day of the same year, he was crowned in London, marking the beginning of the first Anglo-Norman dynasty. Once his new realm was at peace, William instituted the feudal system and proved himself to be an able ruler. The “Bayeux Tapestry“, an iconic needlework measuring 70 meters, would depict the fantastical narrative of William the Conqueror. This tapestry, both a piece of beauty and a crude means of political expression, would ensure this Viking’s great-great-place grandson’s in history.

The origins of William the Conqueror

William was born at Falaise in 1027. Robert the Magnificent, Duke of Normandy, had an extramarital affair with the daughter of a tanner in Falaise and produced a son. No matter the reason, Robert married William’s mother in accordance with the Viking custom of having several wives. Both the father and the son can trace their ancestry back to Rollon, a legendary Viking leader who eventually made his home in Normandy. Many obstacles stand in the way of the young Norman nobleman who is the product of an illicit affair.

In 1034, Duke Robert made a religious journey to the Holy Land. Just before he left, he called a meeting of all the major Norman lords at Fécamp and requested that they acknowledge his only son, William, as his successor. Unfortunately, Duke Robert became sick on the return trip from Jerusalem and passed away at Nicaea, in July 1035. William was then elevated to the position of Duke of Normandy. He was only 7 or 8 years old.

Anarchy wins the duchy of Normandy

Archbishop Robert the Dane of Rouen, the duke’s uncle, assures the rule of Normandy during Robert the Magnificent’s absence and later becomes a teacher to young William after the death of his father. The seneschal, Osbern the Crépon, whose grandfather, Herfast, was a brother to Gunnor, the duke’s concubine, and the duke’s grandson, Gilbert, Count of Brionne, helped him accomplish this goal. After the death of the archbishop on March 1, 1037, his position was filled by Mauger, the son of Duke Richard II and his mistress Papia. But he lacked his predecessor’s power, and conflicts among the great lords of Normandy flared up rapidly.

Counts, viscounts, and lesser lords, who had been ruled with an iron hand by the dukes Richard I and Richard II, seized the opportunity presented by the seigniorial authority’s temporary absence to indulge their lust for power and break the shackles of feudalism they had found so limiting. Rivalries and animosities amongst the Norman lords, whose position and origins were highly varied (the initial Scandinavians were joined throughout time by men from all areas, particularly Bretons and Angevins), erupted in broad daylight, and the lack of punishment swiftly strengthened their daring. Each settlement put up its own set of fortifications, called a “motte-and-bailey castle”, to show the world who was in charge and to make it easier to attack their neighbors.

In the period of Duke Richard, the duke held sole jurisdiction over significant breaches of public order, including armed house invasions (known as “Hamfara” in Scandinavian law). In this case, the duke did not impose any kind of penalty. As long as people were allowed to get even, violence would continue to escalate.

The conspiracy against Duke William

William, Duke of Normandy, turns 15 in the year 1042. It was at this point that complaints of bastardy first surfaced, and the revolt morphed into a plot with the boy as its target. Up until this point, none of the lords who are very close to William had seen this. All or almost all of the most powerful were descendants of Frilla, therefore the news that Duke Robert’s wife Herleue wasn’t a devout Christian had little impact on them.

Guy of Burgundy or Brionne, the duke’s grandson from his mother Adelaide, is at the center of a well-planned plot to usurp the duke’s position. As the duke’s familiar and the son of count Reginald of Burgundy, he grew up alongside the duke. Once Gilbert, Count of Brionne, passed away, William gave him control of the strategically significant castles of Brionne and Vernon. Hamon Dentatus, Renouf de Bricquessart, Néel de Saint-Sauveur, and the viscounts of Cinglais were all involved in the plot, as was Raoul II Taisson, lord of Cinglais, and another of the duke’s familiars, Grimout de Plessis, who was in charge of an estate of 10,000 acres. The men took an oath to “fervor William”.

What little we do know about these events comes mostly from Wace’s Roman de Rou, which was composed in the c. 1170s. Most of the plotters had returned to the duke’s favor by the time William of Jumièges (Guillaume de Jumièges) wrote in 1070, so he is more evasive. “If I didn’t want to avoid their unwavering hostility, I’d identify them here. Nonetheless, I tell you in my ear, all of you who surround me: it was exactly these individuals who today pretend to be the most devoted, and upon whom the duke has showered the highest honors, “to paraphrase Guillaume de Jumièges (William of Jumièges), who composed it.

The duke’s life was the target of the conspirators’ desire to take his life. The duke, aged 19 years old, went hunting near his Valognes castle in 1046. Duchess’s idiot Golet barged into his master’s bedroom one night while the duke and his family were sound asleep. Ahead of his assault, he overheard the conspirators making their intentions clear. Anxious, the duke springs to his feet with a start. He doesn’t bother putting on his shoes, just grabs a hat and rides out on his horse. The conspirators immediately set out in hot pursuit.

On the run, Guillaume used the great Vey’s path, cutting through Montebourg and Turqueville before entering the Veys Bay late at night via Brucheville, when the tide was low and the fords were safe. After crossing “with great dread and rage at night the fords of the Vire” (Roman de Rou), he arrived at Saint-Clément, where he reflected and prayed to God for safe passage.

Finally, he got back on his horse and continued north, using a route that took him about midway between the coast and Bayeux. Upon waking, he found himself in the little town of Ryes. Both he and his horse had clearly reached their limits. The duke was escorted by Lord Hubert of Ryes to his estate, where the lord presented the duke with a new horse and instructed his three sons to drive them to Falaise. The four men set off and Hubert takes charge of sending the pursuers on the wrong road.

Battle of Val-ès-Dunes

Duke William arrived unharmed at his castle in Falaise. His next move was to seek aid from his suzerain, King Henry I (1008–1060). During the upheaval that rocked Normandy, King Henry did not step in to protect the duke. In fact, he brought in several of the Norman lords who had been expelled for their perfidy at his court. Perhaps under pressure from them, about 1040, he launched an effort to reclaim for himself the fortress of Tillières-sur-Avre, a major obstacle to the expansion of Capetian territory. This castle was built by King Richard II on the border of his state to protect himself from the Count of Blois.

Then the count of Blois ceded the town of Dreux and its surrounding land to the king, bringing the castle of Tillières nearer to the domain of the Capetians. So the King mustered his army, marched up to the castle, and demanded that Lord Gilbert Crespin surrender. Crespin, who knew his way around the ducal court and was friends with Robert the Magnificent, said no. Raoul de Gacé and Duke Guillaume, however, had the king swear that he would demolish the stronghold rather than rebuild it on their behalf, and so they gave him their orders to do it. Gilbert caved, and the king burned the castle, invaded Normandy, pillaged Argentan, and then headed back to Tillières with his spoils. Despite earlier assurances, he had the fortress repaired and a garrison stationed there.

Nonetheless, Henry did not turn down his help back in 1047. Certainly, he had no desire to see Normandy weaken, since it would benefit the Capetian-pressed holdings of the Counts of Blois and Chartres. During the summer of 1047, King Henry I’s army landed on the banks of the Muance River, close to Caen. The King was present during the Mass at Saint-Brice de Valmeray. Duke William’s men joined the king’s that morning. The rebels, meanwhile, had amassed about a league away.

Both armies moved forward and eventually met in the middle, close to the town of Billy, at a location once known as Val-ès-Dunes. Raoul II Taisson is reluctant to act as one of the conspirators. Among the conspirators, Raoul II Taisson hesitates. His knights urged him to go back on his word to “fetch Duke William” and not to go further in the treason. He gave orders for his troops to stand still just as the battle was about to commence, and then he rode to the Duke.

When he got close, he smacked him with his glove and said, “I’m keeping my end of the bargain. When I finally located you, I vowed to strike you. Because I took an oath and I don’t want to lie to you, I struck you. But don’t worry; my erratic behavior is not indicative of my becoming a criminal (Roman de Rou).” The duke expressed his gratitude, Raoul Taisson returned to his soldiers, and the retreating army left.

Battle has officially broken out. Néel de Saint-Sauveur, an infantryman, threw King Henry I from his horse, and the king only survived because the quality of his haubert stopped the spear from penetrating him. Duke Guillaume showed great valor in killing Hamon Dentu. The tide of the battle then changes in his favor. Renouf de Briquessart fled; the rebels turned back and many of them drowned while crossing the Orne at the ford of Athis because the rush was so great.

Restoration of peace in the duchy

The Duke’s triumph quickly put an end to the years of unrest that had plagued the duchy. As a result, nobody questions the duke’s authority any more. Insurgents were put in their place. As a result, Grimoult du Plessis was captured before he could reach his citadel, taken to Rouen, and discovered dead in his cell that very same day. Néel de Saint-Sauveur had his fiefs taken away from him and was exiled to Brittany as a result. Finally, Guy of Burgundy shut himself up in his Brionne fortress. The Duke of William arrived to lay siege to him, but he didn’t bother attempting to seize the formidable citadel. There was a pause of three years. Guy surrendered and the Duke offered him a pardon in exchange for the destruction of the castle. But Guy of Burgundy preferred to leave Normandy and return to his native Burgundy.

The Duke of Normandy called for a Council of Peace and Truce of God in 1047, and with the help of his relations, Archbishop Mauger and Nicolas, abbot of Saint-Ouen, it was held in the brand-new city of Caen, only two locations from the Val-ès-Dunes battlefield. Leaders from the church and the nobility of Normandy met at the gathering. From Sunday night through Monday morning, as well as during major religious holidays, violence was strictly prohibited.

In times such as these, only the Duke would be able to muster an army. The penalties for breaking this ceasefire were excommunication and banishment. Innocent individuals, women priests, and infants were designated as “inermes,” or off-limits. The pledge to uphold divine peace was made on the relics of Saint Ouen, brought from Rouen especially for the occasion, by William’s vassals. In this way, the duke had some chance of restraining the unrest caused by private warfare and, by enforcing the Peace of God, combating the pervasive practices of “hamfara” and personal retribution.

Nonetheless, problems remained. As a result, in 1048, Yves de Bellême, lord of Bellême and bishop of Sées, battled out opponents of his family who had taken up residence in the church he had built. Yves de Bellême was so unimpressed that he set fire to his own chapel in order to get rid of them. William was honored by all his lords in 1049. His half-brother Odon, to whom he had granted the see of Bayeux, was now assisting him.

When William’s authority matched that of the French monarch, competition between the two men ensued. William’s focus is taken away from the Capetians in 1066 thanks to events across the Channel. There is no straight line of ancestry between King Edward the Confessor of England and William. Edward, though, had already promised William the throne a few years before. When the latter started asserting his rights, a local nobleman named Harold came up and took the kingdom with the blessing of the ancient Anglo-Saxon parliament.

Conquering the Kingdom of England

The Norman has no plans to give up and end things for himself. At the end of September 1066, he set sail with his army aboard drakkars and crossed the English Channel to reclaim what was rightfully his. He had rediscovered the warrior air and the spirit of conquest of his Viking forebears. After fending off yet another Scandinavian assault, Harold hurried to see the Duke of Normandy.

On October 14, 1066, during the bloody and drawn-out Battle of Hastings, which eventually went in favor of the Normans, Harold died. On his march to London, a victorious William was given the moniker “Conqueror.” Despite the fact that “conqueror” is more complimentary than “bastard,” the next monarch of England will refuse to accept the moniker since he sees himself as a rightful successor rather than an invader or usurper. An air of Viking-ness, but not an excessive amount.

It is widely agreed that 1066 marks the beginning of England as a country and a major force in Europe. With a new monarch at the helm, England was able to emerge from centuries of internal strife and foreign invasions in a completely different light. While he was in power, several fortifications, notably the Tower of London, were constructed throughout the island to ensure its safety. William immediately went out to assert his dominance and shore up royal power.

He eventually replaced the ancient Anglo-Saxon nobility with Normans, who had joined his cause when he overcame their opposition. The Norman invasion was finally successful in 1070. Two years later, William invaded Scotland and forced King Malcolm III Canmore to pay him tribute.

William the Conqueror: Clever administrator

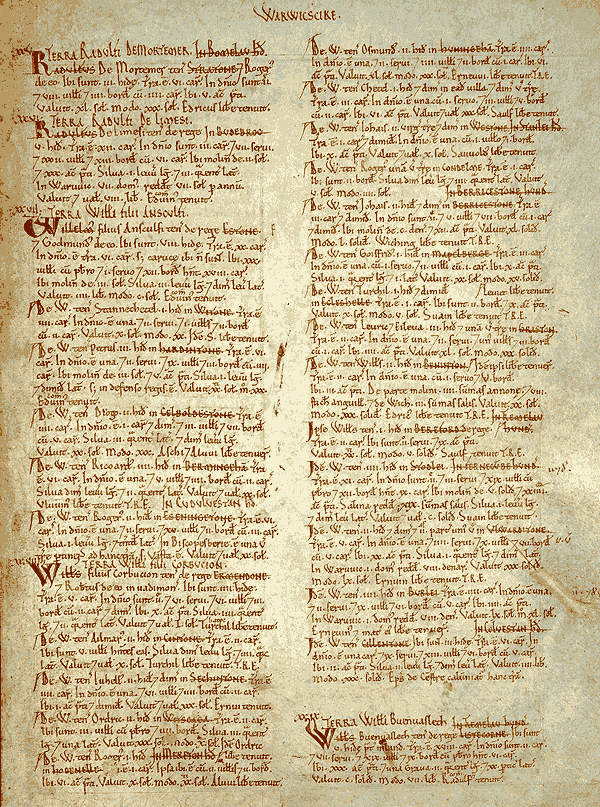

The “Domesday Book,” a census of commodities and people whose rights and obligations were standardized in accordance with the Norman law that he incorporated with the preexisting local norms, was particularly significant. The modern English language has its roots in the (nearly) French he brought with him (the English monarchy still has as its motto in French “Dieu et mon droit”). In addition, he split up the big counties that had been semi-independent under their previous rulers and gave the stolen territory to his obedient Norman slaves. A strong new country emerged under the leadership of a Norman and his wife, Queen Matilda.

William is remembered for forcibly imposing the feudal system on the European continent. To cement the notion of the direct devotion of each lord to the royal authority, he had all the lords swear fealty to him in the oath of Salisbury (1086). William I maintained numerous Anglo-Saxon institutions, including the municipal courts, and the lords were required to accept their jurisdictional power. Courts of ecclesiastical and secular law were kept distinct, and papal influence in English politics was severely curtailed.

William brought over the Channel in his longships more than just a new language and a new law. He was still the duke of Normandy, but his competition with the King of France over the duchy was fierce. With the help of the new French king, Philip I, William I’s oldest son, Robert Courteheuse, instigated a rebellion in Normandy beginning in 1075. So, William made regular trips to the continent to engage them in battle. In 1087, in response to the plundering of Evreux, William burned down Mantes (modern-day Mantes-la-Jolie).

William the Conqueror died on September 9, 1087, at Rouen, after falling off his horse. At the Abbey Church of Saint-Etienne in Caen, he was laid to rest. His son William II took over the leadership of their vast empire after his death.

I. WILLIAM (WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR)

1027 : Birth of William the Conqueror

Around the year 1027, William the Conqueror was born in the town of Falaise in Normandy. He was of the Norman Viking dynasty that Rollon founded in 911.

1047 : Victory of William the Conqueror at Val-des-Dunes

William the First of Normandy, at the time still known as William the Bastard, used his coming of age to fight the rebels who had been ganging up on him ever since Robert the Magnificent’s murder. William, who had narrowly survived an earlier attempt on his life, had the backing of Henry the First and later of Raoul Taisson, a former conspirator, in his effort to win the battle against the vassals at Val-de-Dunes. Many of the defeated drowned in the River Orne, but the triumph was decisive and merciless. The reign of the future William the Conqueror over all of Normandy could then begin.

1053: Marriage of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders

Even though the Pope forbade it, William of Normandy and Matilda of Flanders went ahead and tied the knot nonetheless. William and Matilda were motivated by more than just politics, however. Nonetheless, Pope Leo IX held that fact of a fifth-degree family relationship against them. They constructed two beautiful abbeys at Caen so as not to offend the Church: the Abbey of the Holy Trinity, also known as the Ladies’ Abbey, and the Abbey of Saint-Etienne, also known as the Men’s Abbey. They will receive, respectively, the tombs of Matilda and William.

September 29, 1066: William the Conqueror invades England

At Penvensey Bay in England, William, Duke of Normandy, and his 650 ships disembarked their occupants. After defeating King Harold II’s army at the Battle of Hastings (October 14, 1066), William the Conqueror was crowned king of England.

October 14, 1066: Battle of Hastings

William of Normandy, or the “bastard,” landed in England with a force of four thousand soldiers intending to overthrow King Harold. He had a decisive win and invaded the nation. William, a direct descendant of the Viking duke Rollo, was an excellent choice to succeed to the English crown. Along with the King of Norway and Harold, Earl of Wessex, he is vying for the position of ruler of England. The latter fell in combat after taking an arrow from a Norman archer. After that, William became known as King William I of England. His death resulted in the moniker “William the Conqueror.” One of the 58 scenes on the Bayeux tapestry, created between 1066 and 1077, will depict the Battle of Hastings.

December 25, 1066: William the Conqueror becomes King of England

After his victory at the Battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror was crowned king of England in Westminster Abbey. Thus, he pioneered the use of a gesture that would come to be associated with English monarchs. But there were still challenges for the nascent Anglo-Norman state; England wasn’t fully conquered until the year 1070. Also unique to this kingdom was the fact that William, while being crowned king of England, was still subject to the King of France with regard to the Normandy provinces. This latter group did not welcome the rise of the strong Anglo-Norman monarchy, and Philip I of the Capetians quickly became William’s most formidable enemy.

Bibliography:

- Lawson, M. K. (2002). The Battle of Hastings: 1066. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1998-6.

- Lewis, C. P. (2004). “Breteuil, Roger de, earl of Hereford (fl. 1071–1087)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9661

- Barlow, Frank (1979). The English Church 1066–1154: A History of the Anglo-Norman Church. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-50236-5.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1988). The Kingdom of Leon-Castile Under Alfonso VI. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05515-2.

- Rex, Peter (2005). Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7394-7185-2.

- Bates, David (2001). William the Conqueror. Kings and Queens of Medieval England. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1980-3.