What was Williamina Fleming’s background and how did she become an astronomer?

Williamina Fleming was born in Scotland in 1857 and later immigrated to the United States. She began working as a maid for the director of the Harvard College Observatory, Edward Pickering. In 1881, Pickering hired Fleming to work as a human u0022computeru0022 at the observatory, where she would assist in the analysis of astronomical data. Fleming quickly demonstrated a talent for the work and was eventually promoted to head of the photographic stellar spectroscopy department.

What were Williamina Fleming’s contributions to the field of astronomy?

Williamina Fleming made significant contributions to the field of astronomy, particularly in the area of stellar spectroscopy. She developed a system for classifying stars based on their spectral characteristics, which is still in use today. Fleming also discovered 300 variable stars and 10 novae, and she was the first to discover a white dwarf star.

How did Williamina Fleming’s work influence the field of astronomy?

Williamina Fleming’s work had a significant influence on the field of astronomy. Her system for classifying stars based on their spectral characteristics is still in use today and has helped astronomers better understand the properties of stars. Fleming’s discovery of variable stars and novae also contributed to our understanding of the evolution and behavior of stars.

What was Williamina Fleming’s legacy and impact on the history of science?

Williamina Fleming’s contributions to the field of astronomy paved the way for future generations of women scientists and helped to break down barriers to women’s participation in scientific research. Her work continues to be recognized and celebrated today, and she is remembered as a pioneering astronomer who made important contributions to our understanding of the universe.

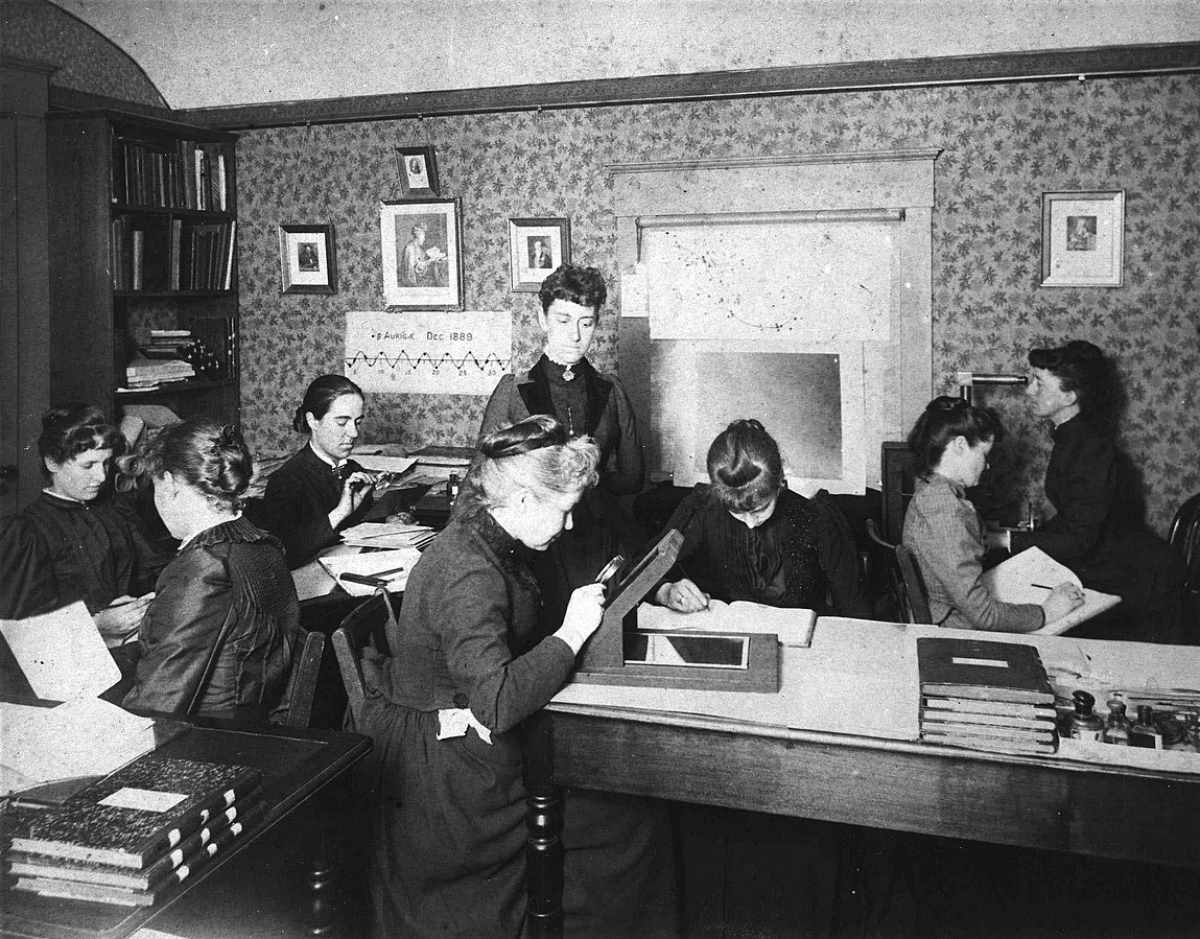

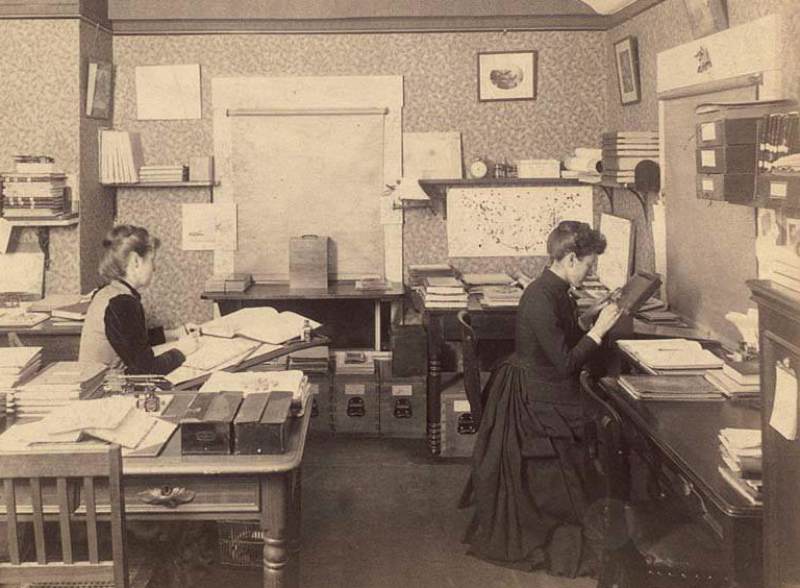

Initially just a maid, the Scottish Williamina Fleming (1857–1911) became a pioneering astronomer in the classification of stellar spectra. Women pioneered astronomy research at Harvard. However, the majority of “Harvard computers” were denied a career. Not so long ago, computers used to sit in front of desks rather than stand on them. Since the early 17th century, the word “calculator” has been used in the English-speaking world to describe someone who does calculations regularly, such as in accounting. Because females could be paid far less than their male counterparts for the same job, an increasing number of women were hired for such computer tasks during the nineteenth century. Additionally, there was a great need for computer power at the time.

Nothing had changed in science, especially not at the Harvard College Observatory (HCO). The reason for this had to do with photography, a cutting-edge technique that had completely new applications for astronomy and was starting to gain traction at the end of the 19th century.

The Harvard Computers

Following his appointment as HCO director in 1877, Edward Charles Pickering and his staff started taking regular pictures of the night sky. The HCO is still renowned for its huge collection of photographic plates. The cabinets of the archive there are stocked with more than 500,000 thin glass plates. Because it used to be possible to take pictures of the stars every night when the sky was sufficiently clear of clouds.

The photographic plates were then examined throughout the day by the Harvard Computers, a division comprised of only female computers. They carried out computations, mapped the night sky, or measured star brightness. They were in charge of extracting the information from the photos, which were afterward examined for scholarly publications. Edward Pickering chose women over men because they were less expensive to purchase than the latter.

The Night Sky Map

The age of astrophysics was ushered in by the advent of photography in astronomy. For example, it was now feasible to learn about a celestial body’s attributes, rather than having to be satisfied with monitoring its location and speed. Things that the human eye is unable to see become apparent thanks to photography.

Consider the light spectra of stars, which provide details about the chemical components they are composed of. It was rapidly discovered during the analysis of the nighttime photographs that not all stars had the same spectra. There were, it seemed, many distinct kinds of stars.

One employee who carried out groundbreaking scientific research at the HCO was Antonia Maury, Henry Draper’s niece, who achieved the first-ever success in photographing a star’s spectrum in 1872. The orbits of so-called spectroscopic double stars were first calculated by Maury.

These are double stars, but because of how closely they circle one another, a telescope’s resolving power is insufficient to tell them apart. They can only be told apart as two stars when their light spots are broken up into their different colors.

From Being a Maid to Being an Astronomer, Williamina Fleming

About 80 women worked at the observatory as “Harvard Computers” in the decades before and after the turn of the century. Williamina Fleming was among those in a unique position. She began working for Institute Director Pickering as a domestic worker, then, after a while, switched to secretarial duties, and finally started producing star classifications.

She cataloged more than 10,000 stars in nine years, finding 59 gas nebulas, 310 variable stars, and 10 novas in the process. She was the first woman to join the Royal Astronomical Society of London as an honorary member.

A suggestion for star categorization based on the observed spectral classifications was also made by Williamina Fleming. One of the most well-known female astronomers at Harvard Observatory, Annie Jump Cannon, then decided to pursue this suggestion.

She invented a technique for classifying star spectra and was the foremost authority on the subject. She was also the first woman to win the prestigious Draper Medal from the American National Academy of Sciences and an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford.

The Henry Draper Catalog, which Annie Jump Cannon maintained after Williamina Fleming’s death in 1940, is the product of the HCO’s mammoth effort in star categorization. The Henry Draper catalog is the first in recorded history to contain the spectral class of innumerable stars in addition to their location and magnitude.

It was solely based on sky surveys. These days, HD numbers are often used to identify many stars. Thus, one of the pillars of contemporary astronomy is the star catalog. But for a long time, scientists didn’t recognize the hard work of most of the Harvard Computers team, which laid the groundwork for the project.

Williamina Fleming’s Life

On May 15, 1857, Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming was born in Dundee, Scotland. From the age of fourteen, the young Mina attended a public school where she alternated between being a student and a teacher. She married James O. Fleming on May 26, 1877, and moved to the US with him. The next year, the young couple made their way to Boston.

Williamina Fleming had to look for employment after her marriage fell apart in 1879, so she accepted a maid position from astronomy professor and director of the Harvard College Observatory Edward C. Pickering. She was given a temporary job at the observatory by Pickering, and by 1881 the young woman had accepted a permanent research position. She took engaged in the study of stellar spectra throughout the next 30 years. Williamina Fleming was chosen as the Harvard astronomy collection’s curator in 1898.

However, the work of this astronomer in classifying star spectra is what has made her most well-known. She examined the tens of thousands of celestial photos taken for the Draper Catalog, a project honoring New York amateur astronomer Henry Draper. Williamina Fleming found more than 300 variable stars, 59 nebulas, and 10 novas throughout the course of her research. She also developed the first photographic magnitude scales for gauging stars’ varying brightness.

The Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra (1890), A Photographic Study of Variable Stars (1907), and Stars Having Peculiar Spectra (1912) are a few of her more notable works. Scottish Williamina Fleming was the first American citizen to be chosen for membership in the Royal Astronomical Society of London in 1906. Later, Annie Jump Cannon drew inspiration from her work and created a brand-new system for identifying stars. On May 21, 1911, Williamina Fleming passed away in Boston, at 54 years old, due to pneumonia.

References

- Smith, Lindsay (14 March 2015). Williamina Paton Fleming. Project Continua. Vol. 1.

- Barker, George F. (1887). “On the Henry Draper Memorial Photographs of Stellar Spectra”. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 24: 166–172.

- Alex Newman (28 August 2017). “Unearthing the legacy of Harvard’s female ‘computers'”. BBC News.

- Ogilvie, Marilyn Bailey (1986). Women in Science: Antiquity Through the Nineteenth Century: a Biographical Dictionary with Annotated Bibliography. MIT Press. p.