What was the role and life of women in the Middle Ages within medieval society? Their existence varied according to age and social status, their place within the family, their role in the couple, their relationship to sexuality, and the fundamental role of motherhood. The very mystery of childbirth inspired fear in men and, by itself, justified the idea that women were demonic beings, capable of enchanting and bewitching. From young girls to grandmothers, from peasant women to nuns, including noble ladies, it is an entire world—long overlooked—that is only now being rediscovered.

- The Young Woman in the Middle Ages

- Women’s Work in the Middle Ages

- Beauty Standards

- Witches

- Marriage in the Middle Ages

- The Married Woman’s Code and Domestic Violence

- The Church and Sexuality

- Pregnancy, Childbirth, Contraception, and Intimate Hygiene

- Rape and Prostitution in the Middle Ages

- Religious Life of Women in the Middle Ages

- Entertainment and Leisure

- Widowhood and Old Age

- Noble Women and Women of Letters

The Young Woman in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, a young woman’s life was divided into three stages: childhood, which lasted until the age of seven; youth, until fourteen; and womanhood, from fourteen to twenty-eight. After this, a woman was considered old, whereas a man was not deemed old until he reached fifty. Canon law set the age of majority at twelve for girls and fourteen for boys. Once past the dangers of early childhood, girls were still regarded by clerics as imperfect beings, little creatures devoid of reason. However, they were granted a degree of purity and innocence, which had to be preserved through strict discipline.

At birth, well-born children were entrusted to a wet nurse, while poor women raised their own newborns. The baby was bathed and then wrapped in linen if they were wealthy, or in hemp if they were not. A diaper cloth was placed over this, crossed at the front. The baby was swaddled with bands of linen or hemp to keep them upright, and in winter, a small cap called a béguinet covered their head. When little girls began to walk, they wore a shirt like boys, along with a long, split robe in red, green, or striped fabric. Poor families made these from old garments. Around the age of two or three, the child was weaned— a crucial stage, as one in three children died before reaching the age of five. Poverty often led to abandonment, especially of girls.

At seven, boys and girls followed different paths. In wealthy families, girls learned to spin with a distaff, embroider, or weave ribbons. This was also the age at which they could be offered to a monastery or betrothed. In rural areas, girls remained with their mothers, helping with household chores, farm work, weaving, and tending animals. They grew up within large sibling groups, where older children played an important role. In the 12th century, the Dominican Vincent of Beauvais advised educating girls in chastity and humility. Mothers therefore ensured that their daughters were modest, hard-working, and obedient.

As for noble girls, they were often placed in convents from an early age, where nuns taught them reading, writing, and needlework. The jurist Pierre Dubois even suggested that they should learn Latin, sciences, and some medicine in the Middle Ages. As a result, they were often better educated than boys, who were primarily trained for war. However, the destiny of a medieval woman was focused on a single purpose: marriage and motherhood.

Women’s Work in the Middle Ages

Even after marriage, women engaged in many professions during the Middle Ages. In towns, they could work in trade, textiles, and food production—such as baking, brewing, and dairy processing—or as laundresses, seamstresses, bonnet-makers, washerwomen, and servants. However, their wages were significantly lower than those of men.

In the countryside, women participated in farming, animal care, household management, spinning and weaving linen, baking bread, preparing meals, and maintaining the fire. And of course, they cared for children. While peasant women were expected to run their households, bourgeois and aristocratic women had to learn how to manage servants, acquire skills in singing and dancing, behave properly in society, and master sewing, spinning, weaving, embroidery, and estate management—especially in their husband’s absence.

The Church viewed educated women with suspicion, emphasizing religious instruction above all. A young girl who had reached puberty was a source of fear and was closely watched by her parents. Female beauty, both feared and desired, was an object of fantasy for men. Clerics associated it with the devil, temptation, and sin, yet it was also celebrated in the ideals of courtly love, inspiring knights and troubadours alike.

Beauty Standards

In the 12th century, the ideal medieval woman was expected to be slender, with a narrow waist, wavy blonde hair, a complexion like lilies and roses, a small rosy mouth, white and even teeth, long black eyes, a high and smooth forehead, and a straight, delicate nose. Her hands and feet were refined and elegant, her hips narrow, her legs slender yet shapely, her breasts small, firm, and high-set, and her skin extremely pale. These beauty standards remained unchanged from the 12th to the 15th century. By the late Middle Ages, the preference for a broad forehead became so extreme that women pulled their hair back excessively and resorted to hair removal. They used various cosmetic tricks to conform to the male ideal.

Witches

For centuries, women were seen as embodiments of evil. Witch trials, which were an outpouring of hatred against women, were the culmination of long-standing clerical misogyny. As daughters of Eve, women were blamed for humanity’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden in collusion with the serpent, and they were believed to be unable to resist casting spells. It was even thought that they could magically “steal” a man’s virility through a spell known as the nouement de l’aiguillette. Accused of black magic, sorcery, and enchantments, so-called “heretical” women were burned by the thousands during the Inquisition.

The first witch condemned by an ecclesiastical court was burned in 1275.

Until the 15th century, many nervous disorders were attributed to demonic possession, provoking fear and loathing. These afflicted individuals were thought to be creatures of the devil. In 1330, Pope John XXII intensified witch trials. In 1487, two German Dominican monks, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, wrote Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), which became the standard legal text for witch trials for the next two centuries. This work fueled an unprecedented witch hunt in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was not until the 18th century that these monstrous trials ceased, thanks to the rise of rational thought and the influence of Enlightenment intellectuals.

Marriage in the Middle Ages

Marriage in the Middle Ages was arranged by parents in all social classes. Among the nobility, it was a means to strengthen or create alliances between territories, increase landholdings, and amass wealth. Women were the subject of negotiations, sometimes even before they were aware of it. If a wife failed to produce male heirs, she risked repudiation—something not condemned by the Church. In 15th-century Flanders, the average age of marriage for women was between thirteen and sixteen, while for men, it was between twenty and thirty. This age gap had two major consequences: short-lived marriages and frequent remarriages. In other social groups, it was the father who chose a husband for his daughter, with negotiations taking place between the respective families.

The bride brought a dowry from her parents, following the Roman tradition, which could take the form of property, land, or livestock. The groom also provided a dowry for his wife.

During the Merovingian era, an additional “morning gift” was given the day after the wedding. Together, the husband’s dowry and the morning gift formed the dotalicium or douaire, which served as a form of financial security for the widow. In rural areas, families often had to save or go into debt to cover the wedding feast, the bridal trousseau, and the dowry. Marriage was as much a social act as a private one. This is why female relatives, friends, and neighbors accompanied the bride in preparing for the wedding night, offering her a lesson in sexual education. She was now ready to fulfill her duties as a wife and mother.

The Married Woman’s Code and Domestic Violence

Charter of the Married Woman and Domestic Violence

The author of the Ménagier de Paris outlines the behavior expected of a good wife: after her morning prayers, she should dress appropriately for her social status, and she should leave the house accompanied by respectable women, walking with her eyes lowered, avoiding looking to the left or right (many representations from this time depict her with her eyes modestly lowered).

She is to place her husband above all men, with the duty to love, serve, and obey him, refraining from contradicting him in all matters. She should be gentle, kind, and amiable, and when faced with his anger, she should remain calm and composed. If she discovers his infidelity, she should confide her sorrow only to God. She must ensure that he lacks for nothing, maintaining an even temper.

It was common, and sometimes even recommended, for husbands to beat their wives during the Middle Ages. In the 13th century, the customs of Beauvais allowed a husband to correct his wife, especially in cases of disobedience.

Brutality and depravity were often exemplified by many of the Merovingian kings. It was easy to accuse a wife of adultery and imprison her, or even kill her, to remarry, since legislative sources confirmed the supremacy of the husband within the home, which he abused with impunity. This violence was found across all social classes.

However, there were instances of happy marriages, but it was considered inappropriate to speak of them—such matters were not to be discussed. Among the aristocracy, courtly love, with its rules and customs, allowed young people to experience the emotions of love without overstepping the boundaries.

The Church and Sexuality

In the Middle Ages, the Church only sanctioned sexuality for the purpose of procreation. Even in antiquity, Stoic philosophers opposed bodily pleasures, and this view persisted into the medieval period. A woman was considered impure during her menstrual cycle and was expected to avoid intercourse, as was the case during pregnancy.

The Church also imposed strict restrictions on sexual relations between spouses, forbidding them during religious holidays such as Lent, Christmas, and Easter, on saints’ feast days, before communion, on Sundays (the Lord’s Day), and on Wednesdays and Fridays (days of mourning). Clergy members sought to contain excessive passion by severely limiting its expression. Failure to adhere to these rules could even lead to an accusation of adultery—between husband and wife!

Pregnancy, Childbirth, Contraception, and Intimate Hygiene

Since a married woman’s primary role was to bear children, infertility was highly stigmatized. However, pregnancy and childbirth were life-threatening experiences for young mothers and their babies due to a lack of medical knowledge, proper resources, and especially poor hygiene. Many women died during labor or from postpartum infections such as puerperal fever.

Even minor complications—breech births, twins, or prolonged and difficult labor—could be fatal for the mother. Thus, the joy of fulfilling their societal role was accompanied by deep anxiety. Maternal mortality peaked between the ages of twenty and thirty. If a woman died in childbirth, the midwife had to quickly perform a cesarean section to extract the baby and administer an emergency baptism (ondoiement), as the Church believed this would prevent the child’s soul from wandering in limbo.

Childbirth was the exclusive domain of midwives, whose knowledge was passed down through generations. After delivery, the mother was considered impure and was forbidden from entering a church for forty days, at which point a priest would perform a purification ceremony known as les relevailles. The new mother, guided by the experienced women in her family, was expected to care for her child, with boys being valued more highly than girls. If both parents were absent, the child was placed under the protection of godparents, sometimes multiple, to increase the chances of survival.

To avoid frequent pregnancies, women relied on herbal concoctions, potions, amulets, and even induced trauma—methods strictly condemned by the Church. In desperate situations, some resorted to abandoning their newborns or, in extreme cases, infanticide. To prevent such tragedies, the Church decreed in 600 AD that impoverished mothers could leave their infants on church doorsteps, allowing priests to arrange adoptions among parishioners.

Rape and Prostitution in the Middle Ages

A constant threat to young girls and married women, rape was committed both in times of peace and war. Rarely punished, it left victims to bear the shame of dishonor and the fear of pregnancy. Feudal lords often exercised droit de cuissage (the so-called “right of the first night”), which allowed them to sleep with a newlywed bride without her or her husband’s consent. Only the rape of a high-ranking noblewoman was punishable by death.

If a woman became pregnant from rape, she was often blamed, as society believed she was somehow responsible. During wartime, sexual violence was tragically common, and no woman, regardless of age or status, was spared. Conquering forces engaged in pillaging, arson, rape, murder, and brutality with impunity, making medieval life especially dangerous for women, who bore the heaviest burden of these atrocities.

During the Middle Ages, both the Church and secular authorities held an ambiguous stance on prostitution. While they officially condemned it, they also considered it a necessary evil. Many women who turned to prostitution had been dishonored by rape, abandoned after bearing the illegitimate children of their masters, or forced into destitution as laborers. The rise of urban centers from the 12th century onward led to the establishment of brothels, where prostitutes were confined to specific areas to prevent them from roaming the streets and setting a “bad example” for other women.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, widespread war and epidemics pushed more women into extreme poverty, leaving them with few options for survival other than prostitution. Medieval society viewed women in rigid dichotomies: they were either pure or public. A girl who was raped, regardless of her innocence or ignorance, was often permanently labeled as a “fallen woman,” making reintegration into society nearly impossible. Many women who began as chambermaids in public bathhouses (étuves) found themselves coerced into brothels.

Wealthier prostitutes attempted to dress like bourgeois women, despite sumptuary laws requiring them to wear distinctive clothing. The writer Christine de Pizan, an early advocate for women’s rights, denounced such societal hypocrisy and the degradation of women. Eventually, the Church established charitable institutions for repentant prostitutes, offering them an opportunity to escape the cycle of vice, take religious vows, or even marry.

Whether noblewomen, peasants, craftswomen, nuns, recluses, “fallen women,” or accused witches, medieval women lived vastly diverse experiences. Their lives merit continued exploration, especially the contributions of educated and literate women. Through their writings—poems, psalters, and various treatises—they left a lasting imprint on history. Alongside these manuscripts, inquisitorial trial records offer valuable insights into the daily lives and struggles of women during the Middle Ages.

Religious Life of Women in the Middle Ages

The first monastery was established in Gaul in 513. In the 6th century, during the Merovingian kingdom, religious communities, often founded by women, multiplied: Queen Radegund founded Sainte-Croix, Queen Bathilde established an abbey in 656, and others appeared in Normandy. The Carolingian era saw the creation of numerous monasteries thanks to donations from royal families. After the violent period of Viking raids, new abbeys emerged around the year 1000, followed by Benedictine communities affiliated with the Cluny order. Women’s monasteries primarily recruited daughters from noble families, as a dowry was required to enter the convent.

In this era deeply marked by faith, some women had a genuine religious calling, while others saw monastic life as a way to escape marriage, secure a safe and comfortable existence, or gain access to education and culture. Abbeys could also receive widows and noblewomen along with their families in the absence of their husbands. Candidates for the veil had to renounce all their possessions and follow the strict rules of Saint Benedict. After the noon mass, one hundred strikes were sounded on a cymbal to signal the sisters to prepare for the meal, giving rise to the expression “être aux cent coups” (literally, “to be at one hundred strikes,” meaning to be overwhelmed).

The abbess, who governed the monastery, was often appointed by princely families and had to be over thirty years old. She oversaw a staff of assistants, including officers, prioresses, portresses, cellaresses, and nuns. Professed nuns held authority over novices, lay sisters, oblates, and servants. This hierarchy ensured the proper functioning of the community. A few men were admitted to monasteries as well, including farmhands responsible for agricultural work and the priest who officiated mass. Monasteries also served as educational centers where girls and boys, starting at the age of seven, were taught reading, writing, the Psalter, and sometimes painting.

Abbeys lived in self-sufficiency. In the 11th century, double monasteries began to develop—on one side lived monks, and on the other, nuns, separated by enclosures and grilles. However, the Church viewed this arrangement with suspicion, and it eventually became subject to conciliar and civil prohibitions. (It was even reported that many infants were secretly entombed as a result of this cohabitation.) Some women, seeking to atone for their sins and devote themselves entirely to God, practiced strict reclusion, living in a small stone cell called a reclusoir. The door was sealed, leaving only a small opening to receive food. This choice was preceded by a solemn ceremony of definitive renunciation of public life.

These cells were often built near a church, cemetery (such as the Cemetery of the Innocents), or a bridge where passersby could consult the recluse and ask for prayers on their behalf. The golden age of reclusion lasted from the 11th to the 14th century. By the 12th century, nuns belonged primarily to the Benedictine or Cistercian orders, followed later by the Dominicans and the Poor Clares. All monasteries were required to provide shelter for travelers and pilgrims. Religion permeated cultural life and played a fundamental role in the lives of medieval women, whether they were nuns or laywomen.

Entertainment and Leisure

Despite being deeply occupied with their work, rural women still found opportunities to converse at the village fountain or the mill. In the evenings, they gathered in small rounded rooms called écraignes, spinning wool with their distaffs while chatting together. Others spent their evenings with family by the fireside.

The Évangiles des quenouilles (literally, “The Distaff Gospels”) depicted elderly women discussing a wide range of topics during gatherings between Christmas and Candlemas, reflecting many popular beliefs widespread in Flanders and Picardy at the end of the 15th century.

Festivals, both religious and secular, provided opportunities for entertainment. In May, village boys had the right to esmayer the young women—an old custom in which they would gather with the girls’ consent and, on the first Sunday of May at dawn, place tree branches in front of the door of the one they admired. This charming tradition is referenced in literary and artistic documents. Family celebrations brought together both aristocrats and peasants, with women playing a prominent role.

During agrarian festivals, queens were sometimes elected. Rural dances, called caroles, brought men and women together in circles and processions around trees and fountains, moving to the rhythm of love songs. Other dances included the tresque or farandole, the trippe (similar to a jig), the vireli (a turning dance), the coursault (a type of gallop), and the baler du talon. These dances provoked the ire of moralists, as the touching of hands and feet, along with the close proximity of dancers, was believed to encourage sin! Fortunately, these condemnations had little effect.

Lords and sovereigns organized lavish banquets followed by sophisticated dances, where ladies adorned themselves in their finest attire. The highlight of a medieval feast came during the entremets, when entertainers such as singers, jugglers, storytellers, and minstrels showcased their talents. In 1454, nobles and aristocrats eagerly attended the famous Feast of the Pheasant. Board games were also popular, including chess, jonchets (similar to pick-up sticks), and card games, which emerged in the 15th century. The jeu de paume, the ancestor of tennis, remained a favorite pastime among the nobility. Some noblewomen engaged in falconry, hunting with hawks or sparrowhawks.

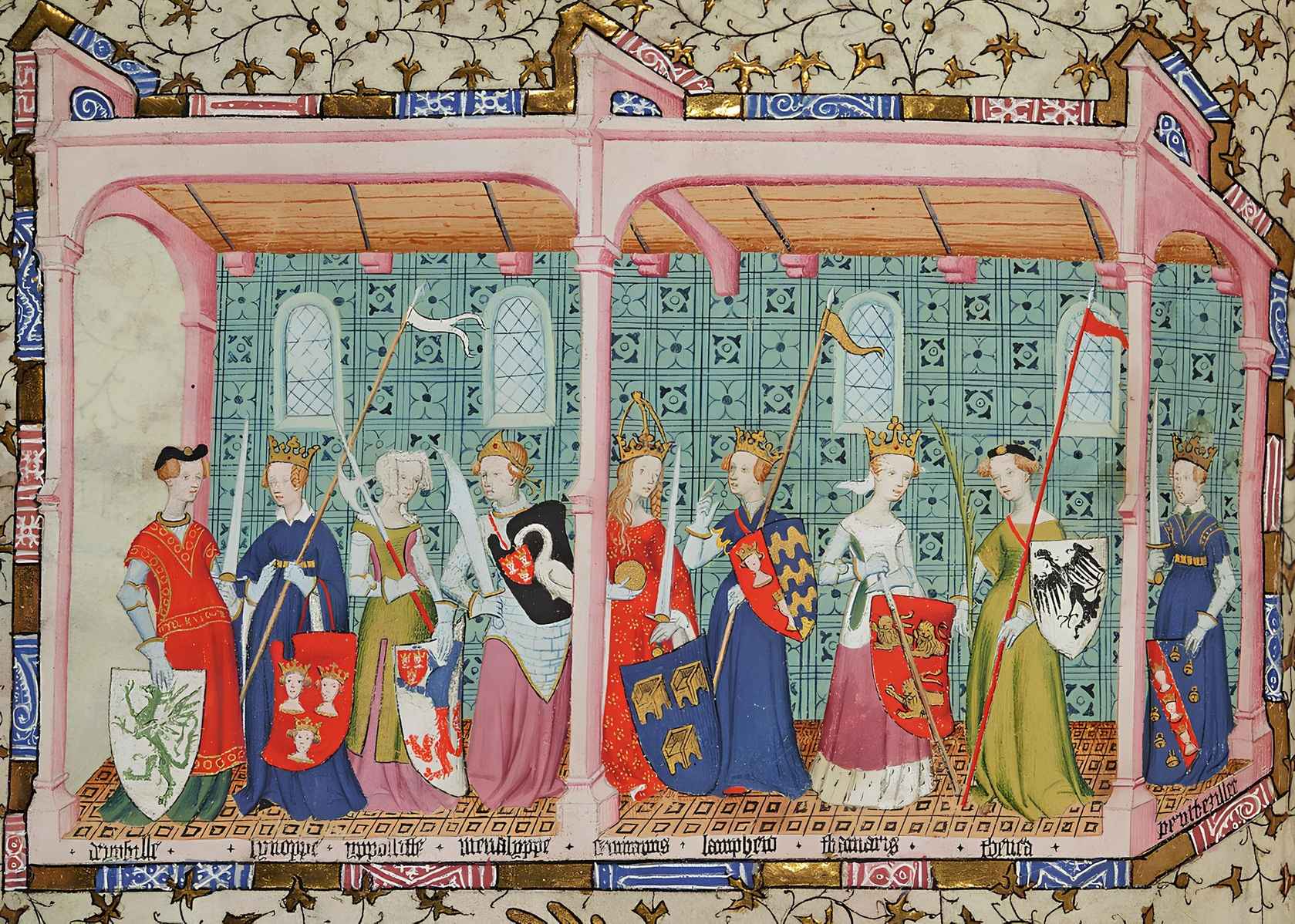

Travel, while primarily undertaken for business or official matters, also served as a form of leisure. Jousts and tournaments provided lords with an opportunity to test their skills and offered a grand spectacle for noble ladies. These events were strictly governed by the codes of chivalry, with women honored as the audience.

Street performers—including animal trainers, acrobats, jugglers, musicians, and storytellers—attracted crowds of onlookers. Processions and princely entrances dazzled the public, with streets cleaned for the occasion and decorated with flowers and draped fabrics. Small theatrical performances, known as histoires or mystères, were held near churches or at crossroads. Theater was a major attraction in medieval towns, with women attending alongside their noisy children. Medieval music, singing, and public readings were highly appreciated by the nobility, and young girls received musical instruction as part of their education.

Widowhood and Old Age

As a consequence of epidemics and wars, many women who married very young found themselves widowed with young children in difficult financial conditions, which pushed them to remarry. Aristocrats had little choice, as they needed support to defend their domains, and they also faced pressure from their families who wanted to use them to form new alliances. When children were adults, their mother could remain with them, her assets remaining incorporated into the family patrimony. If she wished to remarry or enter a convent, she could reclaim her dowry or dower, but her heirs preferred to pay her an annuity.

These situations often generated conflicts of interest and endless lawsuits within families. A young unmarried widow was viewed with suspicion, with doubts about avarice or lust weighing upon her. In towns, however, she could continue to run her workshop or business, or establish a small enterprise. In her book “The Three Virtues,” Christine de Pisan, herself widowed very young, advises women to ignore gossip, to show wisdom, to pray for their deceased husband’s salvation, and encourages young widows to remarry to escape poverty and prostitution.

Women of the time experienced several matrimonial lives and had children from different fathers. Wealthy widows attracted covetousness; they were often kidnapped and remarried against their will. By the end of the Middle Ages, family control was so strong that women had no choice; parents took charge of arranging their successive unions. How was a widow who managed to remain one supposed to behave? She had to wear simple black clothing, conduct herself with dignity, and frequently attend church services.

The elderly woman was rather denigrated; at sixty, she symbolized ugliness and was associated with witchcraft, religious art attributed her with an evil role. The age of mortality was between thirty and forty years for women, forty to fifty years for men on average. Gregory of Tours cites cases of women of advanced age for the time: Queen Ingegeberge, wife of Caribert, the nun Ingitrude… Some Abbesses reached seventy or eighty years in the countryside or among the aristocracy.

Noble Women and Women of Letters

Two categories of women participated in medieval cultural life: secular women of noble birth and nuns. Educated, they protected writers and artists, composed scholarly works, and studied languages and poetry. At King Clotaire’s court, Radegund received extensive literary education; Fortunatus speaks of her readings from Christian literature. According to Einhard, Charlemagne desired the same liberal arts education for his daughters as for his sons. Dhuoda in 841 composed a work for her son William and appreciated poetry.

Around the year 1000, the Ottonian court included many educated women, Adelaide, wife of Otto I, Gerberga, niece of this emperor who spoke Greek and studied classical authors. In the 12th century, Heloise knew philosophical and sacred quotations, spoke Latin, and according to Abelard had studied Greek and Hebrew. Adela of Blois in 1109 is cited in Hugh of Fleury’s work “Universal History.” The love of letters and arts is found among the ladies of the 14th and 15th centuries.

Eleanor of Aquitaine reigned over troubadours around 1150. She protected courtly poetry and rendered judgments in André the Chaplain’s treatise on “Courtly Love.” Writers orbited in her circle under the influence of the Latin poet Ovid. Her daughter Marie of Champagne would write numerous works and also protect letters. In the 12th and 13th centuries, female literature was represented by many writers addressing religious or secular themes.

Hildegard of Bingen, called the prophetess of the Rhine, born at the end of the 11th century to a noble Rhineland family, was offered to the Lord at eight years old, took her vows at fifteen, then was elected Abbess around forty. She authored three works: “Know the Ways,” “The Book of Life’s Merits,” and “The Book of Divine Works,” born from her visions. She traveled extensively, corresponded with the great figures of the earth – emperors, bishops, lords, and noble ladies. She also composed the “Book of Simple Medicine” illustrated with herbals, a bestiary, and a lapidary. Her “Causae et curae” is a manual of practical medicine and pharmacology.

At the end of the Middle Ages, Christine de Pizan would become the first woman to make a living by her pen. Herself the daughter of an astrologer and physician, becoming widowed very young with a family to support, she created works in verse and prose dealing with love and wisdom, emphasizing loyalty and fidelity. Ballads, rondeaux, virelais, and other lyrical pieces allowed her to exercise her rhetorical virtuosity.

She would be protected by French princes: Charles V’s brother, Duke of Berry, Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, Charles VI, Louis of Orleans, Louis of France…. Several of her works would be translated. It was therefore not uncommon to encounter educated women writers in these periods of history.

The medieval period covering ten centuries, the role of women evolved, sometimes regressed depending on laws and economic or demographic realities. Eventually, women would become the subject of passionate debate at the center of a Christian West that doubted and questioned… Since then, the “quarrel” of women has never ceased to stir society.