For the first time ever, 49 tanks took part in the Battle of the Somme on September 15, 1916, during World War I. Soon, these “tracked armored vehicles” would develop into tanks that could traverse rivers and dense woodland. Although the tank has a lengthy history, it wasn’t until the introduction of the internal combustion engine and tracks at the start of the 20th century that it was able to become a functioning armored vehicle. The tanks altered the fate of two global wars, ended positional warfare, and completely changed the way that war is fought.

- From siege towers to the first armored vehicles

- Tanks to end positional warfare

- The first “tracked armored vehicles” prototypes

- The first French tanks

- The first British tanks

- General Haig deploys the first tanks in history on the Somme

- The Battle of Flers-Courcelette

- The British tanks at the front, from Bullecourt to Cambrai

- The Battle of Cambrai

- The Renault tank is adopted by the French

- Like a historical irony

From siege towers to the first armored vehicles

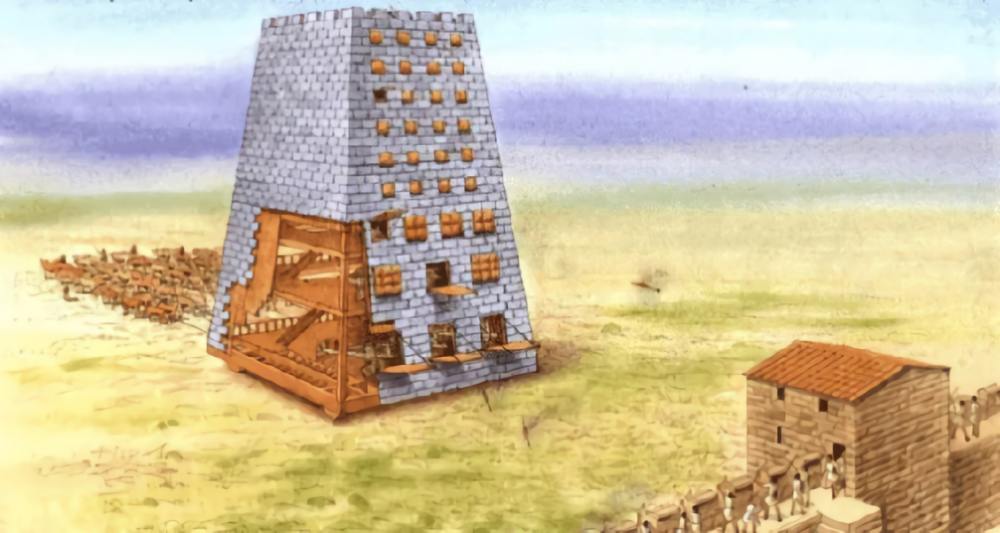

How do you advance while hiding from enemy fire? Military strategists have been plagued by this absurd question throughout history. In fact, it seems that the concept of a mobile weapon defending its passengers predates the very concept of combat. The Greeks constructed enormous siege towers known as Helepolis in antiquity. The Assyrian archers used mobile defenses, siege engines that could hold two men, and enormous water ladles that enabled them to put out a potential fire.

To shield their warriors on the battlefield, the Chinese created the Dongwu Che. The Romans possessed movable turrets that were on wheels, shielded, and catapult-equipped. War elephants were successfully deployed by the Persians and Indians. The Czechs and Poles possessed steel “battle chariots” in the Middle Ages. Eventually, Leonardo da Vinci drew up designs for a wheeled combat vehicle with guns that could be propelled by human strength.

The majority of these weapons were used during sieges, when tactical formations and movements weren’t as crucial. However, the Industrial Revolution’s technical advancements threatened to transform combat into a massive siege, anticipating positional warfare and trench warfare, making this issue urgently in need of solving. Armored trains are another example of mobile weaponry. Even though they are capable of carrying large loads, railways continue to influence how they travel. They are also quite defenseless.

Although they are capable of assaulting ground targets, aircraft cannot take over land. The British were the first to utilize armored vehicles, which were excellent in battle but unsuited for navigating rivers, marshes, uneven terrain, or even trenches (due to the small contact area between the wheels and the ground).

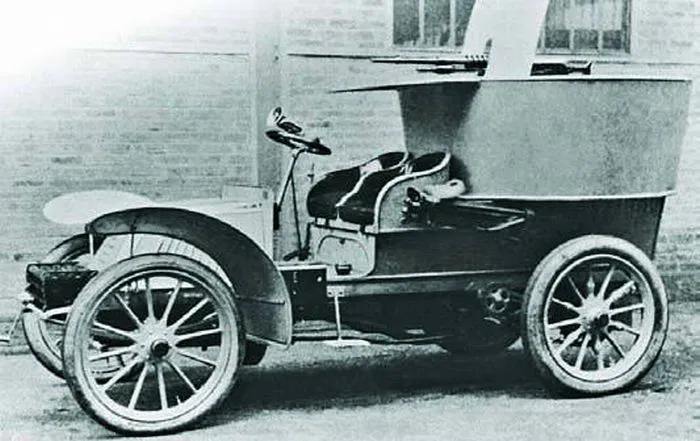

This field made considerable advancements in the years before World War I, especially with the widespread use of automobiles and the development of spark-ignition engines (gasoline engines). Along with the development of armored vehicles, new vehicles known as machine guns or self-propelled weapons (which were effectively machine guns or cannons mounted on vehicles) were also created. The Motor Scout (the first armed petrol engine powered vehicle ever built), a quadricycle flanked by a Maxim machine gun and partially covered by light armor, was created by Frederick Richard Simms in 1898 and was the first armored vehicle in Britain.

Tanks to end positional warfare

In reality, the British were the first to think of developing a new kind of vehicle with tracks, armor, turrets, and numerous weapons to address the issue of moving forward under enemy fire. The Land Ironclads, a short story by British author Herbert George Wells that appeared in The Strand Magazine in December 1903, described the use of enormous, heavily armored vehicles that could maneuver over any terrain, be armed with cannons and machine guns, and be able to cross a system of fortified trenches in order to clear the terrain and aid the advance of the infantry.

Military historian Ed Ellsworth Bartholomew wrote about an armored car built in 1902 by the French firms Charron and Girardot & Voigt that included a Hotchkiss machine gun and 7 mm of protection. According to Spencer Tucker and Priscilla Mary Roberts’ World War I encyclopedia, the Austro-Daimler turreted armored vehicles were created by the Austrians in 1904 (based on the designs of Lieutenant Colonel Graf Schonfeld of the Austro-Hungarian army), and these vehicles were used in the Italo-Turkish War in 1911–1912.

According to military historian Bruce Gudmundsson, who wrote the book On Armor, World War I contributed to the emergence of a new need for heavily fortified self-propelled weapons that could traverse any terrain, bringing about the inevitable development of “tanks,” which were first used by the British against Dutch colonists during the Second Boer War in 1902. Thus, during World War I, the deployment of armored vehicles was a response to the pressing need to end positional warfare, a necessity that itself repeated the old issue of moving forward while hiding from enemy fire. Because armored vehicles are difficult to handle, except on flat ground, additional advancements seemed to be required.

These “tanks” function on the premise of deploying firepower comparable to that of artillery and machine guns across the void between the trench networks while shielding their passengers from enemy fire. The infantry was to be accompanied by the tanks in order to penetrate the front, allowing the cavalry to take advantage of the opening. It was essential at all costs to produce an all-terrain vehicle that could guard against infantry assaults, cut through barbed wire, eliminate machine gun nests, and march alongside the men.

Few military strategists of World War I realized that the internal combustion engine would usher in a change in the art of battle, despite being presented with the horror of the war of position after a few weeks of combat. The advent of vast mechanized forces that would replace the cavalry in battle was foreshadowed by the installation of this engine in tanks and aircraft, which would shortly boost their mobility and combat effectiveness. These mechanized units would develop into World War II’s armored divisions twenty years later.

Any-terrain armored vehicle development intensified during World War I, as stated by French Army Colonel Jean-Baptiste Eugène Estienne on August 23, 1914: “Gentlemen, the victory in this war will belong to which of the two belligerents which will be the first to place a gun of 75 [mm] on a vehicle able to be driven on all terrain.”

In Collision of Empires: Britain in Three World Wars, 1793–1945, Arnold D. Harvey explains how the British and French developments were almost simultaneous in this regard. Indeed, Colonel Estienne was struck at the same time as the British with the notion that a weapon with the characteristics of the future tanks was required to aid the infantry, according to the British war correspondent on the Western Front, Ernest Dunlop Swinton (he was chosen by the Minister of War, Herbert Kitchener).

Two months before the Little Willie, the prototype Mark I tank, was tested in England, the French began exploring armored vehicle designs in January 1915 and started testing them in theory in May. In January 1915, the French started researching and planning for armored vehicles, with testing beginning in May. This was two months before the English tested the Little Willie, the Mark tank I prototype. French military planners were putting the Schneider CA1 prototype armored vehicle—the first French tank—through its paces at Souain as the British Little Willie was being produced as the first-ever tank prototype and the first working tank in the world.

The first “tracked armored vehicles” prototypes

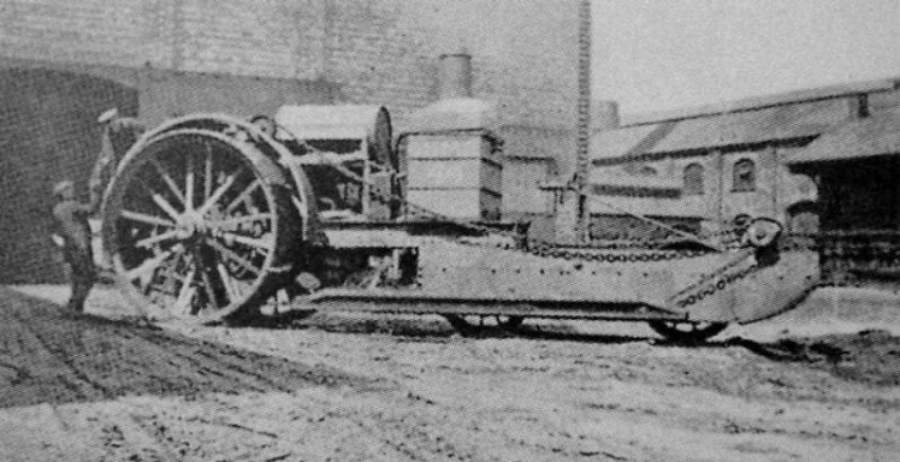

These “tracked armored vehicles” were originally constructed as prototypes around the turn of the century. Captain Léon Levavasseur of the French Army and a polytechnician proposed a vehicle project to the Ministry of War in 1905 that was later renowned as having all the characteristics required for tank design, including a 75mm gun mounted in front of a sort of steel box and self-propelled by articulated wheels. Three men and ammo could have been carried by this self-propelled artillery, which could be used on any surface. On August 13, 1908, the Ministry’s plan for a “mobile artillery piece” was officially discarded since British engineer David Roberts had previously created a vehicle with a similar function, the Hornsby. A few years later, in 1911, the ideas for tanks that the Australian civil engineer Lancelot de Mole and the Austrian military engineer Günther Burstyn were to build were similarly rejected by their respective governments.

Nevertheless, tracked armored vehicles began to be marketed in 1908, particularly in the US. They were also utilized by the French Army to transport their large artillery pieces through difficult terrain from the start of World War I.

The Boirault machine, which was intended to cut through barbed wire and gain ground on the battlefield, was also tested by the French between 1914 and 1915. This vehicle’s parallel tracks revolved around a powered triangle center. But since it was still too flimsy, sluggish, and impractical to control, it was swiftly given up.

The first French tanks

The French construction engineer Paul Frot presented the French Ministry with plans for an “armored roller” in December 1914, despite the fact that it lacked tracks. On March 18, 1915, he tested his Frot-Laffy prototype, which managed to cut through the barbed wire but was found to be excessively sluggish and not particularly agile. Thus, the “Estienne Tractor” developed by General Estienne took the place of this project.

The Aubriot-Gabet Fortin, which was propelled by an electric wire and equipped with a 37-mm naval cannon, was one of the 1915 French attempts to construct massively armored and armed vehicles placed on tractor chassis, but it proved to be useless.

In the same year, in January, the tracked tractors made by the American company Holt were to be studied by Eugène Brillié, project manager for the armaments manufacturer Schneider & Co. After his return from the New World, Brillié, who had previously assisted in the design of armored vehicles in Spain, was able to persuade his business to begin a development study for an armored and armed tractor based on the Baby Holt tractor chassis.

The Schneider factory’s experiments, which started in May 1915, showed how excellent the 45-hp tracked Baby Holt was. New tests were conducted on June 16 in front of Raymond Poincaré, President of France. Finally tested in front of French Army officials at Souain on December 9, 1915, it was the first finished French armored vehicle.

On December 12, Colonel Estienne submitted a concept to the General Staff that aimed to establish a tracked vehicle-equipped armored army. Generalissimo Joseph Joffre authorized the building of 400 tanks in a letter dated January 31, 1916, indicating that the design had been accepted (the order for the production of 400 Schneider CA1s was nevertheless given on February 25, 1916). On April 8, 1916, 400 more Saint-Chamond tanks—the second French tanks—were ordered shortly after. Schneider, however, struggled to fulfill the manufacturing goals; therefore, the tank deliveries from September 8, 1916 were spaced out across many months. On April 27, 1917, the first Saint-Chamond tanks were delivered.

The first British tanks

One significant power to test a number of tank prototypes during the early years of World War I was the United Kingdom. British Army Major Duncan John Glasfurd proposed the notion of a machine with a chain of wheels (referred to as “pedrail wheels“) capable of striking enemy lines as early as June 1914. Lieutenant-Colonel Ernest Swinton, an engineer and war reporter, was only dimly aware of the development of the American Holt tractors and their capacity to traverse difficult terrain in July 1914. However, he freely admitted that he did not realize until September how the tracked vehicle concept related to the need for an all-terrain armed vehicle.

In a letter to Secretary Maurice Hankey from October 1914, Sinwton urged the British Committee for the Defense of the Empire that tracked tractors be armored and equipped for use in battle. Hankey persuaded the War Office in the end, and despite their skepticism, they agreed to test a Holt tractor on February 17, 1915. The War Office temporarily stopped any further development after the project was abandoned because the project’s chain was hindered by mud.

Nevertheless, he continued his testing in May 1915 with the Tritton Trench-Crosser, a machine with enormous tractor wheels with a diameter of 8 feet and carrying beams 15 feet long to enable it to traverse trenches. But since it was too heavy, the vehicle was also left behind.

First time using the word “tank”

British Army officer Ernest Swinton coined the term “tank” in 1915. And the Landships Committee, which the Royal Navy and Winston Churchill established on February 20, 1915, officially agreed to support the testing of armored tractors as “tanks.” Churchill ordered the creation of 18 experimental tanks in March of that year, 12 of which used Diplock tracks (a concept particularly supported by Royal Navy commander Murray Sueter) and 6 of which had big wheels (an idea advocated by Royal Naval Air Service officer Thomas Gerald Hetherington). Despite this, their manufacture was stopped because the rails were too heavy and ineffective, and the wheels were too broad and brittle.

The British gave up on the idea of large tanks in June 1915 due to the failure of so many prototypes. The Landships Committee would now conduct research on scaled-down prototypes. In July 1915, the Bullock Creeping Grip, an American tracked vehicle, similarly failed its test. After being altered, the machine was constructed again as the Lincoln No. 1 Machine on August 11th, 1915, and tested on September 10th. Again, this test was unsuccessful.

Nevertheless, progress was made, with a focus on new track layouts. On December 3, 1915, Little Willie was put to the test. The Centipede or Mother was the first of the Big Willie tanks, and it was designed as a rhomboid to make up for its subpar all-terrain performance. The tests carried out starting on January 29th, 1916, proved to be successful, and on February 12th, the War Office ordered 100 units for deployment in France. In April, 50 brand-new units were ordered. The first British tanks were born.

The British were the first to utilize these tanks on the front in 1916 after becoming convinced of their value. The British referred to these vehicles as “tanks” rather than by their official designation of “landships” in order to conceal their presence in France. Thus, they indicated that the armor plates were created with oil tanks in mind. The Admiralty Secretary of the Landship Committee, Albert Stern, testified that various words like “water tank” or “cistern” had been taken into consideration in his evidence, as described by the Tank Museum in London.

In order to engage these machines in large numbers without the Germans being aware of them beforehand, the British military planned to amass these machines in France in strictest secrecy. Additionally, some of these “tanks” were constructed at the ironically named “tank shops” of Glasgow’s locomotive builders. Despite this, little preparation was given to infantry personnel for battle with tanks because of the secrecy surrounding the construction of tanks and the distrust of most infantry commanders.

General Haig deploys the first tanks in history on the Somme

In order to make progress during the Battle of the Somme, British General Douglas Haig, who oversaw the British troops in France, insisted on having access to the first 60 tanks. After many weeks of attrition struggle, General Haig began a fresh attack southwest of Bapaume on September 15, 1916. 49 tanks were involved in combat between 11 divisions, including 2 Canadian ones. Only 32 made it to the starting line, and only 21 were eventually engaged. The newly formed 41st division was helped by some of them and was able to advance more than three kilometers (1.9 miles).

The 2nd Canadian Division captured the French Courcelette commune with the aid of two of these tanks, and the Germans ultimately lost High Wood during the Attacks on High Wood in the Battle of the Somme. The tanks could not go forward in the forested area, however. Though the conflict lasted for many days, despite these early triumphs, the German defense structure once again showed its power. Additionally, General Haig erred by failing to launch an artillery bombardment prior to the attack in order to shield his tanks from allied fire. German resistance proved to be particularly significant in the places where the tanks were engaged. The bulk of the tanks were rendered inoperable after 10 days of combat.

Obviously, everyone was taken aback when the first tanks appeared on World War I’s battlefields. However, the tanks did not significantly influence how the battle turned out on the Somme. The Allied General Staff had scattered them too far, and the terrain did not favor an armored attack. In fact, the tanks themselves found it impossible to go forward due to the mud. Additionally, the conservative officers’ disdain for them only grew as a result of their underwhelming performance.

Winston Churchill bemoaned, “They have squandered my landships by launching them in tiny numbers. Yet there was a real victory behind this idea.” After that, Ernest Dunlop Swinton was let go as commander of the British armored forces. The War Office even attempted to cancel 1,000 new tank orders after the Somme. And the ministry took advantage of the chance to decrease production from 4,000 to 1,300 tanks when some of them sank, unable to move, during the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917.

The General Staff increasingly lost faith in the tanks rather than challenging their own judgment. More critically, however, was the fact that the Germans had managed to seize three of these British tanks and were working on a missile design to destroy them. In actuality, Haig’s defeat on the Somme was also a tactical catastrophe. Therefore, any unexpected impact brought on by the engagement of armored vehicles was lost.

The French’s first experience wasn’t particularly decisive either; on April 17, 1917, during the massive Nivelle operation, they engaged their tanks. The massive 27-ton Saint-Chamond tanks turned out to be quite weak. Of the 120 tanks, 60 were destroyed by German heavy machine guns and artillery. The crews were burned alive, and the soldiers, who were now without protection, were murdered. The Germans came to the conclusion that a gun would always defeat a tank. But they made an error that would end up being deadly.

The Battle of Flers-Courcelette

The third and last significant attack carried out by the British Army during the Battle of the Somme was the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, which started on September 15, 1916, and lasted for one week.

Haig planned to breach German lines and end the battle of position, much like the first two British offensives during the Battle of the Somme (the Battle of Albert on July 1 and the Battle of Bazentin Bridge on July 14). Haig intended for the 15th Corps to break through the German lines northeast of Flers, enabling the cavalry to penetrate the enemy rear by committing General Rawlinson’s IV British Army and a portion of the Reserve Army (which would later become Gough’s V Army). Most of the forces were given three or four objectives, most of which, if a breakthrough was made, were to be taken on the first day of the fight.

A heavy artillery barrage was fired before the opening assault. A field gun was placed every 65 ft (20 m) from the front of the attack on July 1, while a heavy cannon was placed every 165 ft (50 m). At Flers-Courcelette, where there was a field gun every 30 ft (9 m) and a heavy gun every 85 ft (26 m), these figures were significantly higher. However, one drawback of the artillery barrage was that, since tanks moved slowly, the infantry had to be engaged before the tanks. The artillery barrage must thus spare some of the front so that the tanks could advance. This tactic prevented the tanks from bombing locations where the German resistance would likely play a significant role.

The 14th Corps’ progress on September 15, the opening day of the fight, was uneven. The 56th Division, which was supposed to protect the attack’s right flank, was stopped. The 6th Division confronted an intimidating German defensive position known as the “Quadrilateral” on its left flank, to the north of Leuze Wood. Despite hard fighting, it was unable to make much progress. The Guards Division did not have any trouble capturing its first goals. The battling up to that point had been so taxing that it paused the advance.

The 15th Corps onslaught on the right was more effective, although it fell short of the anticipated victory. 14 tanks were used to assist the assault (4 others were also allocated but could not take part). East of Delville Wood, the 14th Division had to eliminate a concentration of German resistance. Two companies from the 6th Battalion of the Light Infantry Division, “King’s Own Yorkshire,” and one tank were in charge of this assault. Despite losing all of the men, the 5.30 am attack was a success.

The 14th, the 41st, and the New Zealand Division, three divisions of the 15th Corps, mostly succeeded in achieving their goals. The 41st Division, which was tasked with capturing Flers, was given the most tank assignments in the center. Early in the day, the infantry was able to push down the main avenue undercover and conquer the settlement of Flers thanks to one of the tanks. Once the settlement was taken, the advance was nonetheless stopped. The fourth goal, which represented a breakthrough, was not possible to accomplish.

On September 15, the 3rd Corps had both successes and failures. On the left flank, the 15th Division was successful in seizing the settlement of Martinpuich, while on the right flank, the 50th and 15th Divisions were only able to make slow headway. By 8:25 a.m., General Gough’s Canadian Army Reserve Corps had completed its last goal, the capture of the village of Courcelette on the extreme left flank of the British onslaught.

On September 16, the assault was attempted once again without much success. Heavy casualties forced the relief of the Guards Division. At 9:25 am, the 15th Corps began its assault on the center. The 14th Division was unable to advance after an unsuccessful artillery barrage. At Flers, the 21st Division’s advance, which was being spearheaded by the 64th Brigade under General Headlam, was stopped. An artillery round destroyed its only tank. At Flers, artillery also damaged the signal brigade headquarters. Because of the failure on the right flank, the Allied leadership forced the New Zealand Division to cease after repelling a German counterattack and making some small gains. The 3rd Corps, likewise, didn’t make much headway.

On September 17, General Rawlinson ordered the onslaught to resume the next day. Nevertheless, the intended assault was delayed until September 21 before being abandoned. Only the Fourth Army front in the eastern region of Morval saw further fighting. The British conducted a number of small assaults in the last seven days of the Battle of Flers-Courcelette to strengthen their positions, particularly in the area of “High Wood,” where the Germans formed a bulge after the defeat of September 15. Beginning on September 18, the rain became harder, making all attack attempts futile.

Overall, the fight of Flers-Courcelette was a lot more successful than the onslaught of July 1st, although it fell short of its primary goal of breaching the German defenses. The British forces were very close to reaching the German rear, but the German General Staff had shown that it still had enough reserves to re-establish its defenses. Due to the great hopes for this new weapon, this fight also saw the introduction of tanks to World War I battlefields.

The British Mark I tanks performed poorly in action, and General Douglas Haig, the head of the British troops in France, received harsh criticism for using this covert weapon so soon. The French government had sent Colonel Jean-Baptiste Eugène Estienne and Under-Secretary of State for Inventions Jean-Louis Bréton to London to persuade the British government to revoke Haig’s order, and he had also been forewarned by the commanders under his command, including Ernest Dunlop Swinton. However, it was conceivable that the German High Command’s perception of tanks as inefficient weapons was incorrectly reinforced by their poor performance on the Somme, causing them to postpone their own tank development initiatives. The knowledge obtained from the Flers-Courcelette Battle also helped to enhance tank design.

The events of the Battle of Cambrai (November 20 to December 7, 1917) needed a more nuanced explanation, notwithstanding the possibility that the confrontation of tanks on the Somme could support the hypothesis that the surprise effect was lost. The tanks gathered in Cambrai were able to breach the German defenses. Even though the German counterattack prevented this victory from being capitalized on, it showed that the Germans had not created an anti-tank weapon that was sufficiently potent.

The Courcelette Memorial, located on the D929 (Albert-Bapaume), south of the town of Courcelette, is the ultimate memorial to the deeds of Canadian troops on the Somme.

The British deployed their Mark tanks on the Somme in 1917 despite the uncertain beginning. After the Battle of Cambrai, it became clear to all the staff that using tanks in large numbers was the most effective way to cut through enemy lines while causing the fewest number of losses, especially in front of trenches that were very strongly defended.

The British tanks at the front, from Bullecourt to Cambrai

The Allies in 1917 contemplated a rupture in the front line due to two offensives—one French at the Chemin des Dames and the other British in front of Arras. During the attack on the small town of Bullecourt, which is southeast of Arras, the British General Staff used Mark tanks again.

With 12 tanks and no artillery backup, two Australian brigades assaulted Bullecourt on April 11th, 1917. The Australians were forced to leave after coming under enfilade fire. Out of a total strength of 3000 troops, the 4th Brigade suffered casualties amounting to 2258. In addition, the Germans seized 1137 soldiers and 27 officers while only suffering 750 losses. The 62nd and 2nd Australian Divisions launched a second assault on the village’s sides on May 3, 1917. Bullecourt was eventually taken, although the Hindenburg Line prevented the British from doing so. 14,000 troops were lost by the British and Australian forces combined.

The MK-I tanks and a few new MK-II vehicles dispatched to Bullecourt’s wintry terrain were likely nailed to the ground. Not because of the terrain, but rather because the tanks’ armor was penetrated by the new German ammunition. Five of these “K” type ammunition were seen by the German infantrymen to be mounted on machine guns.

The British did, however, learn their lesson. They went through how to attach the armor plates. As a result, the new MK-IV tank had stronger armor that could withstand the Germans’ unique ammunition. The tanks’ interior ventilation systems were also enhanced and overhauled. At Messines, the MK-IV saw combat in June 1917.

General Philippe Pétain made the decision to stay on the defensive while anticipating the arrival of the American tanks and infantry after the failure of the Nivelle attack and the slaughter at the Chemin des Dames. The head of the British Expeditionary Force, General Douglas Haig, decided to launch a significant attack in Flanders. His first maneuver was to seize the Wytschaete Ridge (5 mi/8 km long and sometimes 276 ft/84 m high). The British General Staff believed they could lessen the salient at Wytschaete since the settlement of Messines (south of Ypres) was encircled by merely a hill and no ridge. This was the assignment given to General Herbert Plumer’s Second Army.

About 75 MK-IV tanks were involved, and their purpose was to assist the troops rather than to actually manage the breakthrough (their main task was to clear the machine-gun nests). This time, there had to be extensive artillery preparation. In fact, General Herbert Plumer had mandated a 17-day buildup up to the assault, which was scheduled for June 7.

“Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography,” Marshal Herbert Plumer told his staff before the combat.

To avoid being seen, the tanks had to arrive the day before the combat. Additionally, any communication between the tanks was masked by the noise produced by their movement. So that the armored forces could get to their positions, ground markers were required. Guides were required to lead the tanks since there were no markers. Some armored crews were forced to locate their locations independently using drawings or the infantry’s climbs as they were without both markers and guides. They were fatigued before the combat even started after they reached their objective.

One of the Allies’ most effective offensives of the war was the Battle of Messines. Following the explosions, the Australian and New Zealander forces of the British and Commonwealth launched an offensive and rapidly succeeded in capturing the southernmost tip of the ridge. Some forces broke through the second German line in under two hours, and the Allies secured Messines and Wytschaete at 7 a.m. with the aid of Irish soldiers from the 16th and 36th divisions. The cannon was advanced as the British soldiers began to retreat down the ridge’s eastern side.

The tanks and the reserve infantry started to engage in combat early in the afternoon. Finally, the goals were accomplished at around 3:10 PM. The British were successful in holding the crest, burying themselves, and stopping the German counterattacks. Compared to earlier tank battles, the MK-IV tank and infantry teamwork at Messines was far better. The German machine-gun positions were destroyed by the tanks, making it simple for the troops to take over the area. They offered the infantry support points, even though they were slowed down. However, this attack did not demonstrate their entire capability. Again, supplementary goals were given to the tanks. But they demonstrated that they were capable of more than just aiding the troops.

For a while, armored commanders had been pressuring the general staff to drastically alter how tanks were used. They were satisfied when they specifically requested that the tanks be utilized on relatively level ground that had not previously been artillery fired. The first Cambrai fight established their accuracy.

The Battle of Cambrai

The western front appeared to stay frozen until the weather improved during the third Ypres combat in 1917. The German and British personnel, however, had different plans. To undo the disaster of Flanders, General Haig planned a fresh course of action. As the German lines were not as strongly guarded as they were elsewhere, he came to the conclusion that the Cambrai area was the most appropriate for such an onslaught. As a result, Haig put up an army with substantial artillery and tank support, but because of the severe casualties in Flanders and the activity on the Italian front, he was unable to accumulate reserves. He had the benefit of surprise due to the lack of reserves, but he was unable to make use of it.

Due to how little artillery fire it had endured, the Cambrai area was selected. Its open and level terrain seemed perfect for large-scale combat with armored vehicles. In Cambrai, new methods for firing artillery were also used. Now that enemy locations could be predicted, firing was adjusted using maps rather than merely by looking at the sites of impact. As a result, artillery barrage fire was more precise and effective, and the bombardments’ surprise factor was reinstated since firing preparatory salvos was no longer required.

Despite this, the Germans had created broad and deep anti-tank trenches. The British planned to line up three tanks, each with a large fascine. The first person would pitch his fascine into the trench, followed by the next two people who would walk over it.

The Battle of Cambrai began with the British Third Army under General Julian Byng. The main assault, spearheaded by Mark IV tanks, targeted a portion of the Hindenburg Line guarded by the German Second Army under General Georg von der Marwitz. The goal of General Byng’s strategy was to breach the German defenses positioned between the North and Scheldt Canals. The troops and tanks were to capture the Bourlon crest before moving northeast into Valenciennes, while the cavalry was to move quickly on Cambrai.

On November 20, 1917, a short bombardment of 1,000 artillery pieces was fired in an effort to crack the Hindenburg Line’s defenses. 476 tanks spearheaded the main onslaught (about 380 in the front line and 100 in reserve). It was the first significant use of tanks in the World War I . Six of General Byng’s 19 divisions moved 5 mi (8 km) down the front in front of these tanks. The first assaults were successful. The Hindenburg Line was breached by 5.5 mi to 7.5 mi (9 to 12 km) in certain locations, with the exception of Flesquières, where the Germans vigorously fought and neutralized numerous tanks. Additionally, the British tanks’ lack of effective communication with the troops slowed their advance.

The British struggled greatly to keep up their rate of advancement despite the significant success they had achieved since the first day of the fight. Numerous tanks had mechanical issues, were caught in cracks, or were destroyed by German artillery fire at close range. West of Cambrai, the action was centered on the Bourlon mountain.

The German forces fighting against General Byng’s Third British Army started launching counterattacks on November 30 in an effort to reclaim lost territory. The Second Army under General von der Marwitz, which had so far resisted most of the offensive, received a significant amount of reinforcements from Prince Consort Rupprecht of Bavaria, commander of the endangered region.

The employment of a brief barrage, the introduction of new stormtrooper formations (Sturmtruppen, as against the Russians in Riga), and the assistance given to the front-line soldiers by low-flying aircraft all contributed to the German counterattacks’ exceptional effectiveness. The British were obliged to give up a lot of the hard-won land because they were overextended and short on reserves. On December 3, General Haig gave the order to leave the salient, and on December 7, all of the British-conquered territories were abandoned, with the exception of a section of the Hindenburg line at Havrincourt, Ribécourt, and Flesquières. The Germans took control of some territory south of Welsh Ridge.

The tanks at Cambrai had to retreat if they couldn’t hold the position by themselves. But as time went on, it became more evident to all the staff that mass tank engagement was the most effective means to breach enemy defenses while causing the fewest possible casualties, especially in front of fortified trenches.

The Renault tank is adopted by the French

Due to their slowness and poor maneuverability, the heavy Saint-Chamond tanks were swiftly favored over the light Renault, Berliet, and Schneider tanks by the French General Staff; yet, the Saint-Chamond tanks, which could traverse the 6.5 ft (2 m) cuts alone, were not abandoned. The Renault FT-17 and Schneider C.A.1 in particular were mass-produced, allowing the Allies to assist its offensives with substantial armored vehicle deployments.

During the second Marne counteroffensive on July 18, 1918, in Villers-Cotterêts, French tanks achieved their first significant victory. From then on, the tanks took part in all assaults despite the significant damage inflicted on them by the Germans (50 percent per engagement). Without them, no new discoveries were ever thought of.

The rotation was also guaranteed by the 500 brand-new tanks that arrive at the front each month. Thus, 1,500 French tanks were put on the line in August 1918 against equal numbers of British tanks, and on August 8, at Amiens, the British tanks, commanded by General Rawlinson, had a major strategic victory. The Germans had controlled a sizable portion of the railway line between Paris and Amiens since Operation Michael in March 1918, and the goal of the allied offensive was to free it.

General Rawlinson’s Fourth British Army, which had to move slowly over a 16 mi (25 km) front, was in charge of the attack. A short artillery bombardment preceded the assault before the 11 British divisions involved in the initial phase of the assault advanced in a little over 400 tanks. The British onslaught was backed by the left wing of General Eugène Debeney’s First French Army.

The Second Army of General Georg von der Marwitz and the 18th Army of General Oskar von Hutier supported the German defenders. There were 14 divisions in line and 9 divisions in reserve for the two German generals. The German forces were forced to retire 9 mi (15 km) as a result of the Franco-British onslaught, which was a full success.

The General Staff was really concerned about how the German army was acting since it looked to portend a terrible outcome for the continuance of hostilities. Despite the new German anti-tank weaponry, several frontline troops simply left the battle without putting up much of a fight (Gewehr 1918). Others—roughly 15,000 soldiers—quickly abdicated. After hearing the news, General Ludendorff, Deputy Chief of the General Staff, characterized August 8 as a “dark day for the German army.” But nothing changed for the better. The next day, several further German troops were captured.

The Battle of Amiens shifted south of the salient controlled by the Germans on August 10. The Germans were compelled to leave Montdidier as the French Third Army advanced against it, letting the Amiens-Paris railway route reopen.

On August 12, the Allied offensive’s initial phase came to a halt due to heightened German resistance. But it was evident that they had lost. 40,000 German soldiers were killed or injured, and 33,000 were captured. 46,000 men were lost by both the French and the British.

The Battle of Amiens, where the new British MK-V tanks made up the majority of the assault battalions, went down in history as the largest tank fight of World War I. The armored tanks seemed to already be in control of the battlefields, with the cavalry alone having been annihilated in certain locations or forced to escape in front of German machine gun positions.

Like a historical irony

Instead, the German army was a latecomer to this area and never accepted the armor’s effectiveness. There were just 20 German A7V tanks made in 1918; they were “armored boxes” with little agility. The usefulness of tanks was nevertheless verified in the last battles of World War I.

Under the command of a certain Lieutenant-Colonel George Patton, who would go on to make a brilliant distinction during World War II, the American Army engaged 267 French-made tanks, including FT-17s, during its first major “independence” operation at the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in September 1918. More than 2,000 French tanks were on the front lines in November 1918, with the French having manufactured 4,146 tanks during the whole World War I as opposed to 2,542 for the British.

The Allies in WW1 produced around 6,700 tanks. The tanks that would soon be called “the victory tanks.” Tanks that a handful of zealous German officers, including Heinz Guderian, studied after the war in order to avenge the defeat of 1918. Heinz Guderian described them as “if they succeed, triumph will follow.” Ironically, these same tanks were used to destroy the French Army two decades later, giving the German Army their retaliation.

Bibliography

- Charles River Editors and Colin Fluxman. The Tanks of World War I: The History and Legacy of Tank Warfare during the Great War (2017)

- Watson, Greig (2014). “Hotel where warfare changed forever”.

- Harvey, A. D. (1992). Collision of Empires: Britain in Three World Wars, 1793-1945. A&C Black. ISBN 9781852850784.

- Foley, Michael. Rise of the Tank: Armoured Vehicles and their use in the First World War (2014)

- Townsend, Reginald T. (1916). “Tanks” And “The Hose Of Death”.