Yule Goat, also known as Julebukk and Christmas goat, is an umbrella term for a variety of traditional winter solstice practices that focus on goats in Norway, Scandinavia, and Northern Europe. In Swedish, it is referred to as julbock and julgumse in the Dalecarlian dialect.

In Danish, it is called julebuk, juleged, and nytårsbuk. In Estonian, it is called joulosak, while in Latvian, it is called joulopuk. Although the Yule goat’s precise origin is unclear, the many traditions surrounding it as a representation of Yule, a Yule spirit, a leader of carnival processions, a giver of presents, and other similar roles have their origins in both pre-Christian and Christian traditions. Religion, festivals, and subsequent agricultural practices are all part of the Yule goat, as are beliefs from the Germanic and Norse cultures.

Origins of the Yule Goat

Was the Yule Goat a Sacrificial Goat?

The term Yule goat or “julebukk” might have originated from the pre-Christian practice of slaughtering a billy goat in honor of “jól,” which means “Midwinter Day,” in order to guarantee a prosperous year. This practice was favored either to celebrate fertility, wish for a happy year, or signal the end of the harvest season.

Thor’s Goats: Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr

Another origin theory of the Yule goat lies in mythology. Some have seen the Yule goat as a symbol of the Norse deity Thor. Two goats, Tanngrisnir (gap-tooth”) and Tanngnjóstr (“teeth grinder”) dragged Thor’s chariot. Even if he ate the goats, they would revive the next day, provided he collected all the bones from their skins. The terrifying sound produced by his chariot as he raced across the sky is called Thor’s thunder (torden). When the giants heard Thor, they would duck for cover.

Perhaps as figures of abundance and holy protection, these two goats may have made it into Christian Christmas decorations. At one point, the Yule goat was the bringer of gifts in Nordic regions before Santa Claus became a more popular Christmas figure.

Goats may have stood for virility in Norse mythology, but in ancient Greek mythology, for instance, goat-like satyrs were symbols of intense desire. Goats were associated with negative and animalistic ideas, which were particularly prevalent in medieval Christian beliefs about sexual restraint. Other representations of the goats throughout this period included the devil, witches, and people damned to hell. Krampus is a half-goat Christmas figure, and he is the polar opposite of Saint Nicholas or Santa.

The Yule Goat and the Wild Hunt

Folklore has it that “julebukk” (Yule goat) may also mean “Julebukking,” or someone who gets into the spirit of the season by dressing up as a billy goat and begging for food and drink. This person’s attire is often a furry hide. The myth of “Oskoreia,” or Wild Hunt, describes a variety of specters that wandered around during the midwinter night, often accompanied by a horned figure like a goat. It is an old belief recognized from the Middle Ages and here we find a potential link between the Yule goat and the Wild Hunt.

The leader of the Wild Hunt is often a figure associated with Odin in Germanic legends. In this theory, the origin of the Yule goat may lie in this group of demonic or ghostly huntsmen. Because in the later centuries, the celebrations of the Yule often saw a person with a billy goat mask and animal hide leading a group of people in old clothing, which symbolized the dead.

They celebrated Yule by dancing and making a racket. At this period, the Yule goat was more of a nuisance than a kind spirit, and he often wanted more than just a handful of sweets.

His appearances at parties were unannounced, and while everyone knew he was really only a friend in a horny guise, the fearsome beast still frightened kids and even adults.

Different Norwegian towns, cities, and generations have their own unique customs when it comes to celebrating Yule or Christmas with goats. Traditionally, both adults and youths would go out “julebukking” during the Christmas season in search of sweets as a reward, but nowadays, the practice is largely associated with kids. The main part of the excitement in julebukking was trying to identify the person behind the Yule goat disguise. Whenever adults went somewhere, they would historically be given a dram or a small quantity of spirits (liquor).

Features of the Yule Goat

Bringer of Gifts

One of the many Victorian-era uses for the Yule goat was as a gift-bringer, where he later became the helper of Santa Claus and the puller of his sleigh.

Yule Inspector

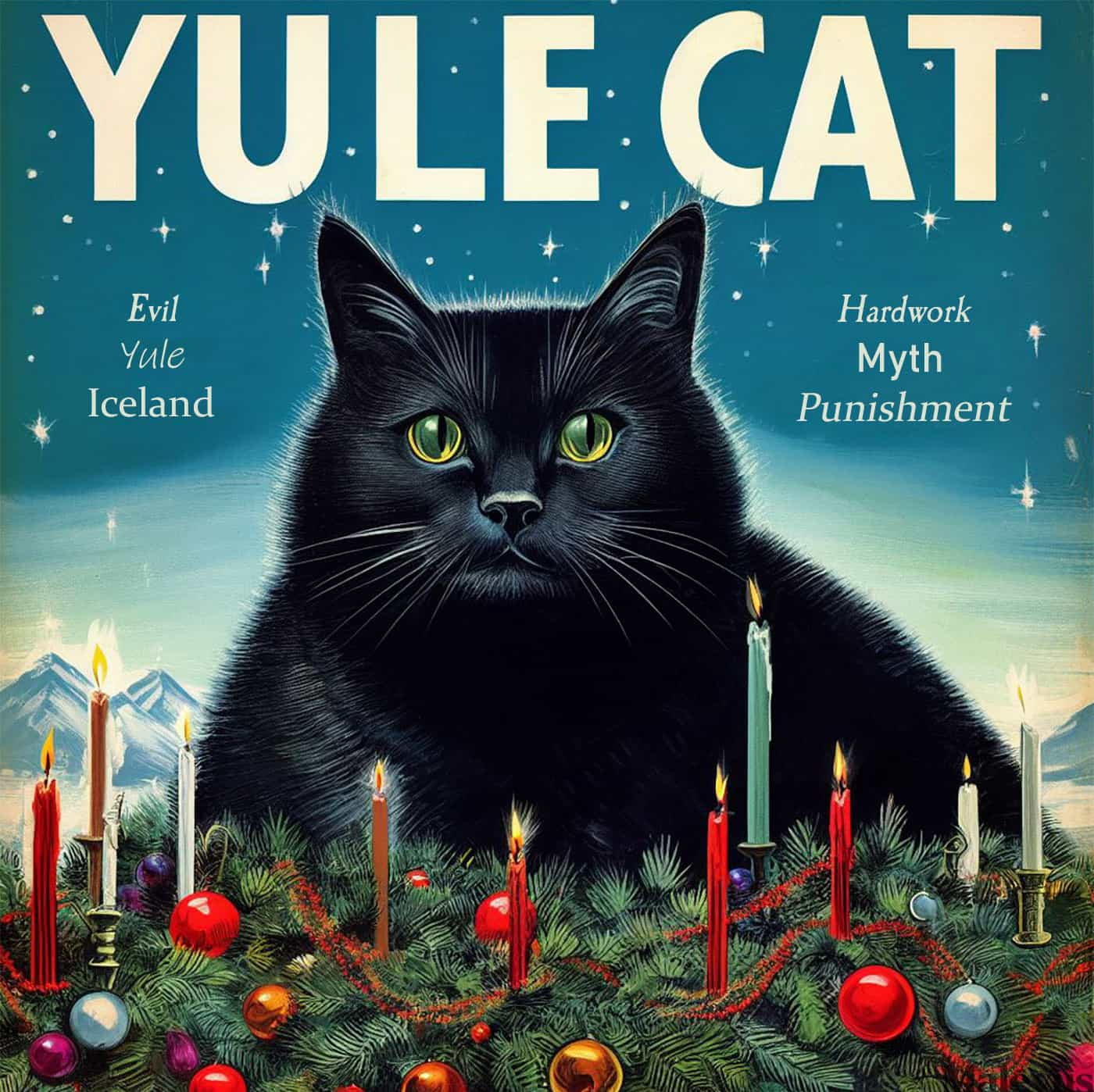

Older stories also associate Yule goat with a malevolent spirit or wight (Danish: “julevaette”) that, like Christmas elves and Lussi, kept tabs on everyone’s holiday preparations, had the power to punish those who disobeyed, and frightened youngsters, just like the Icelandic Yule Cat.

Yule Ornament

The Yule goat later became a Yule ornament made of straw with curled horns and red ribbons. There is now a giant straw Gävle Goat built each year for Yule. Interestingly, the Yule goat has also been used to describe certain kinds of bread, pastries, and even social activities.

These traditions have carried on into Christmas.

A Straw Figure

The goat was an important aspect of pre-Christian Nordic culture, and its influence lives on in the form of a straw figure that is part of the Yule décor today. The significance of the goat is also shown by traditions like hiding a straw goat in a neighbor’s home and then trying to return it in the same way.

The Yule Goat Language

A characteristic derived from old and common masquerade customs is that the Yule goat, like Santa Claus, speaks “gnome language,” “Yule goat language,” or “troll language,” which is a distorted, high-pitched voice. This is also mentioned in the Norwegian writer Alf Prøysen’s well-known Christmas song “Romjulsdrøm” from 1968, which is about being “four years old during the Christmas season” and encountering a “Yule goat at a grandmother’s home.”

Christmas Figures Similar to the Yule Goat

Initially, the timing of the Yule celebration was not fixed, with each village celebrating when the work of harvest and threshing was complete and the livestock had been brought in from pasture. It was only during the first half of the 19th century that the festival began to be celebrated on November 1. Since it coincided with All Saints’ Day, it partly took on a celebration for the deceased.

Krampus

There are many parallels to the Yule goat tradition, especially in the Alpine regions, where a similar pre-Christian figure has survived in a disguised form with goat horns and animal skins named Krampus. He is known by many names according to the countries and regions, such as Klaubauf, Bartl or Bartel, Niglobartl, Wubartl, Pelzebock or Pelznickel, Gumphinckel, Parkelj, Čert, Badalisc, and so on.

Grýla

In Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Shetland, the Christmas goat tradition is linked to Grýla, a troll woman in folklore. People go Yule goat-ing (Julebukking) dressed as supernatural beings. Horns and animal hides are also recurring features of Grýla.

Santa’s Horned Helpers

There are also many figures who accompany the “goat.” St. Nicholas himself brings Krampus to deal with “naughty” youngsters in large regions. A little kid dressed in white with lit candles is worshipped in the Protestant North instead of Krampus, known as the Christ Child (Christkindl).

Zwarte Piet (“Black Peter”), who originally wears horns and is tasked with frightening misbehaving youngsters, is always accompanying St. Nicholas (Sinterklaas/Santa Claus) in the Netherlands. Over the past 150 years, he has become less menacing by assuming the appearance of an African, often in a childlike manner, dressed in exotic servant attire.

What is the Julebukking?

Julebukking is the Norwegian trick-or-treating at Yule in Nordic countries, which is when children dress up to go caroling door-to-door and these kids are called “Yule goats.” Julebukking is a game for kids, also practiced on the 13th day of Christmas (Epiphany), in exchange for treats like cookies, juice, and soda.

Nowadays, “julebukk” (Yule goat) mainly signifies “Julebukking,” a term for a small group of people who went door-to-door dressed for Yule. Once upon a time, there was a group or procession whose members wore shaggy fur and a goat or horn mask for this occasion. Nowadays, it is more common for costumed adolescents to visit farms, where they sing, dance, joke, accept beverages, and receive Yule food.

Despite a gradual decline in popularity since the 1980s, the practice is still alive in Norway and a few other Baltic republics. Kids nowadays can dress as elves, but in newer adaptations, they don’t use masks to hide who they are.

It is speculated that the practice of Julebukking originated in medieval dramatizations of Oskoreia or Wild Hunt, a kind of winter solstice myth, or as a holdover from Catholic processions featuring devil images or southern European mask traditions.