What was Yuri Gagarin’s background, and how did he become a cosmonaut?

Yuri Gagarin was born in the village of Klushino, Russia, in 1934. He grew up in a farming family and later studied at a technical school. He joined the Soviet Air Force in 1955 and was selected for cosmonaut training in 1960. Gagarin was chosen for the first manned spaceflight, Vostok 1, in 1961.

How did Yuri Gagarin influence the Cold War rivalry between the Soviet Union and the United States?

Yuri Gagarin’s flight took place during the Cold War, when the Soviet Union and the United States were competing to demonstrate their technological and military superiority. The success of Gagarin’s mission was a major propaganda victory for the Soviet Union, and it fueled fears in the United States that the Soviet Union was winning the race for space exploration.

What was the scientific significance of Yuri Gagarin’s mission and how did it contribute to space travel?

Yuri Gagarin’s mission was significant because it demonstrated that human beings could survive the rigors of space travel and paved the way for future manned missions. Gagarin’s flight also provided valuable data on the effects of microgravity on the human body, and it helped to establish the basic principles of orbital flight and re-entry.

What were the challenges Yuri Gagarin faced during his mission and how did he solve them?

Yuri Gagarin faced numerous challenges and risks during his mission, including the potential for his spacecraft to malfunction, the possibility of being stranded in space, and the danger of re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere. Gagarin relied on his training and the support of ground control to successfully navigate these challenges and complete his mission.

How has Yuri Gagarin’s flight affected space exploration and scientific research since then?

Yuri Gagarin’s flight was a watershed moment in human history, and it helped to inspire a new era of space exploration and scientific research. Gagarin became an international hero and a symbol of the Soviet Union’s technological prowess, and his legacy has continued to inspire new generations of space explorers and scientists.

How did Yuri Gagarin’s life and career change after his spaceflight?

After his spaceflight, Yuri Gagarin became a national hero in the Soviet Union and a symbol of the country’s technological achievements. He received numerous awards and honors, including the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Gagarin continued to serve in the Soviet Air Force and was involved in the Soviet space program. He also traveled extensively, promoting Soviet space achievements and international cooperation in space exploration.

On April 12, 1961, Yuri Gagarin (1934–1968), a Soviet cosmonaut, made history. He is the first human being to leave the gravitational pull of the Earth behind and enter space. Gagarin launched human space travel by making the first orbit around the Earth in his Vostok-1 spacecraft. He is the first human to reach into outer space and make a flight in space.

Yuri Gagarin’s space flight, however, not only ushered in a new era but also served as the pinnacle and turning point of a bitter, decades-long rivalry between two countries and two men: Wernher von Braun, a German rocket pioneer, on the side of the United States, and Sergei Korolev, a Soviet rocket engineer, on the Soviet Union’s side. Both were excellent engineers and planners, and since they were young, they only had one dream: to get to space.

It was a close race, and it was unclear who would win the race for the first human space flight until the very end. However, with the launch of the Sputnik satellite on April 12, 1961, the Soviet Union surpassed the ostensibly technologically superior United States by achieving a significant space travel milestone. The question is, how was this ever possible? Before getting into how Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space, let’s recall the events leading up to that point.

The First Man in Space

Tyuratam, rocket test site, April 12, 1961, 9:06 p.m.

The first human journey into space was now taking off from this remote location in the Kazakh steppes. A 131-foot (40-meter)-tall rocket was perched on the launch pad of the military complex, which was surrounded by launch towers and is still classified today. A person was inside the 7.5-foot (2.30 m) tall Vostok-1 capsule. The cosmonaut, Yuri Alexeyevich Gagarin, is 27 years old.

The countdown approached zero. The exterior auxiliary nozzles ignited loudly as kerosene and liquid oxygen poured into the main engine. As the rocket body, which was still mounted on the launch tower, vibrated, smoke and flames burst out of the back and surrounded everything at a height of several feet.

“Poyekhali!”

59 seconds after launch, now that the engines had enough power to maintain the rocket’s weight, the critical moment had come. For a short period of time, the Vostok rocket seemed to float weightlessly on its own jet of fire. The launch arms all opened at that precise time, allowing the last brackets to release the rocket. Yuri Gagarin informed the ground station, “Poyekhali!” (Off we go!) Gagarin’s ascent in Vostok-1 began. The orbit of the Earth was Gagarin’s stop.

Only a small number of individuals at the highest levels of the KGB, military, and party were now aware of what was occurring outside of Tyuratam. The people of the Soviet Union, the alliance nations, and most definitely the people of the archrival USA were unsuspecting of anything. The night shift was just starting at the CIA and other surveillance units. It was just after eleven o’clock in the evening on the American East Coast.

Vostok-1 is in Orbit

11 minutes and 16 seconds after launch.

Yuri Gagarin entered Earth’s orbit after the third burn stage, and the protective nose over the Vostok spacecraft was jettisoned as planned. A human left the pull of the Earth and felt the weightlessness of space for the first time in history. “I see the Earth!” Gagarin remarked on the view of Siberia from the viewport of the spacecraft: “I see the Earth! “I can see the clouds; it’s admirable; what a beauty!” Siberia was 124 miles (200 kilometers) below him.

Vostok-1 moved across the Pacific coast and crossed the ocean to South America a little while later. It was still unclear at this time if the probe’s orbital characteristics matched the intended path. Gagarin asked whether or not everything was proceeding according to plan, but he got no response.

The Adversary is Paying Attention

However, Yuri Gagarin’s query was picked up by a different electronic monitoring station on the Alaskan shore, which notified American intelligence and military personnel. Nevertheless, the Soviet news agency TASS eventually reported 55 minutes after Vostok-1’s launch: “The world’s first satellite-ship Vostok with a human on board has been launched into orbit from the Soviet Union. The pilot-cosmonaut of the spacecraft is a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Aviation Major Yuri Alexeyevich Gagarin.”

After the launch of the first man-made satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, the Soviet Union once again outperformed the United States in reaching a significant spaceflight milestone in 1961. The heated competition between the two political regimes for influence, power, and scientific prowess—both on Earth and in space—had reached its current height with the launch of Vostok-1 with Yuri Gagarin as the first man in space. Since the conclusion of World War II, both governments have made every effort to surpass one another in both military and civilian technology, eager to prove their respective dominance.

Yuri Gagarin orbited the globe an hour and 48 minutes after takeoff. The Soviet Union achieved the ultimate victory when Gagarin also landed safely. But how did the Russians defeat the USA with a technologically less advanced system on paper?

Even though the United States and the Soviet Union were rivals during the height of the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s, their respective rocket and space technologies had common origins. They trace their roots back to one man—German engineer Wernher von Braun—in the closing stages of World War II.

Von Braun created his wonder weapon for Hitler first at the Peenemünde Army Research Center and then at the “Mittelwerk” close to the Thuringian town of Nordhausen. The engineer had pushed the development of his “V-2” rocket so far forward in the last year of the war by dishonestly exploiting prisoners from concentration camps that it served as the foundation for the devastating V-2 rocket assaults on London and other Allied objectives in 1944. The missiles caused more than 7,000 deaths in the English capital alone. V-2 was also known as “Aggregat 4” or A4 for short.

With a maximum range of 185 miles (300 km) and the capacity to fly to heights of up to 55 miles (90 km), the V-2 outperformed anything previously seen in more ways than one. It was the origin of the most ambitious and sophisticated missile program in the world for both the United States and the Soviet Union. Their pursuit of sought-after technology is likewise frantic.

Russians Discover a V-2 Wreckage

Moscow, summer 1944, the secret research facility NII-1.

To unmask the V-2’s mystery, the Soviet Union brought some of its most gifted engineers to NII-1. A V-2 wreckage was found following an accident beyond Soviet lines. A heap of steel, broken glass, electrical cables, and smashed cases were taken to the conference room of the institute. The chamber was transformed into a laboratory over the course of the next two months as rocket engineers pieced together pieces of aluminum, electron tubes, and metal plates to recreate Hitler’s “wonder weapon.”

Meanwhile, the Americans captured von Braun, the majority of his staff, and a large number of intact V-2 rockets and brought them to the U.S. The Soviets, upon reaching Nordhausen in Germany after the withdrawal of American troops, once again discovered only half-destroyed V-2 fragments, some of which were purposefully rendered unusable. Stalin said, “This is absolutely intolerable.” “We beat the Nazi armies; we took Berlin and Peenemünde, but the Americans get the rocket engineers.”

Korolev, the Russian “Wernher von Braun”

There were only a few Nazi engineers left, and the Soviets sometimes forced them into helping. The Soviet rocket design agency OKB-1, led by Sergei Korolev, started developing its own version of the V-2 rocket, the R-1 series, in the years that followed. These rockets were mainly developed for military applications, such as intercontinental ballistic missiles.

As part of Stalin’s “great purges,” Korolev was condemned to 10 years in a labor camp in 1938. He wasn’t released until 1944, when aeronautical engineer Andrei Tupolev helped arrange it. Korolev was then given a job working on the Soviet Union’s missile program. He was now seen as the “Wernher von Braun of the Eastern Bloc.” Both historians and contemporary scholars believe that without him, the first man in space would not have had a Russian name. But until his death, his contribution to Soviet spaceflight remained a secret. At most, “Mister X” was how Western intelligence agencies referred to him.

Korolev was acknowledged by the Russian scientist and objector Andrei Sakharov, who worked with him for a time, as “a brilliant engineer and a dazzling personality […].” Korolev dreamed of the cosmos, and he held on to that dream throughout his youth and during his time with the famous GIRD rocket propulsion research group.

At the conclusion of the war, when Korolev was finally permitted to resume his rocket research career, he was determined not to let this chance be lost to him again.

Tikhonravov and the First Manned Spacecraft Ideas

While a scientist at another Soviet research facility was already dreaming about the next major step in rockets, Sergei Korolev and his colleagues were still largely focused on the advancement of the German V-2. Mikhail Tikhonravov, who had previously created the first two-stage rocket engine for the Soviet Union before the war, now aspires to carry humans by rocket in the future, not only across continents but also into space.

His design would place two cosmonauts in the “nose” of a strong, multi-stage launch vehicle, allowing them to reach orbit and be returned to Earth’s surface in a unique landing capsule. The capsule would need to feature parachutes for landing, a heat shield, life support systems, maneuvering thrusters for small trajectory adjustments, a jettison mechanism for burn stages, and unnecessary modules.

“We Should Speak”

Tikhonravov eagerly and persuasively advocated in a speech at the beginning of 1948 for the creation of launch vehicles that could go to Earth’s orbit and carry satellites or possibly people into space. He claimed that the tremendous speeds and altitudes needed for this were technologically possible. But the party leaders and military personnel in his audience, drawn from various institutions, responded to his words with frigid silence.

A senior commander was quoted as saying, “The institute apparently hasn’t had enough to do and has therefore decided to move into the realm of fantasy.” The military’s top priorities from Tikhonravov at the moment are strong multistage engines that would enable long-range missiles to fly even further and navigational equipment that would increase targeting precision.

However, one of the visitors had a different perspective: “We have some serious things to discuss.” Korolev said as he pulled Tikhonravov away. By this time, Korolev had long started to investigate the potential for human space travel. He approached aerospace doctor Vladimir Yazdovsky in January 1949 and asked him to lead a working group on the biological implications of space travel.

Dogs and Rockets

The partnership was successful: on July 22, 1951, Korolev’s team successfully launched two dogs 68 miles (110 km) into the air atop an R-1 research rocket. The dogs named “Dezik” and “Tsygan” were dressed in protective space suits with helmets constructed of acrylic glass just for them. Both animals and their capsule were safely landed by parachute at the conclusion of the rocket flight. They are the first animals to have made it to and returned from such an altitude.

Later, the R-1 alone conducted 14 additional dog flights, while the successor versions, the R-2A and the R-5A, conducted many more. They all demonstrated at least one thing: Flying in a rocket was not inherently fatal for a live organism; in fact, up to a certain point, even the intense acceleration experienced during the launch was practically survivable. This was just the inspiration Korolev and his group needed to go on. A rocket that can also lift heavier payloads to orbital heights was just in need of more thrust.

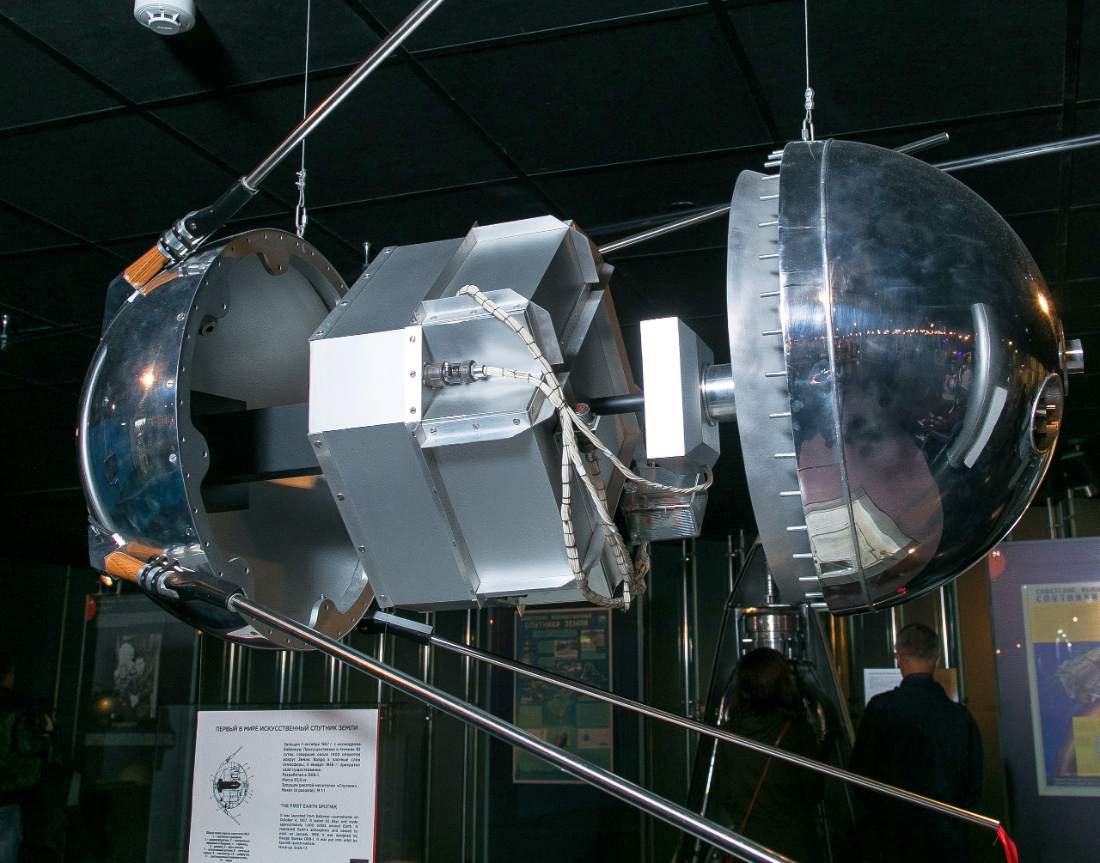

The Sputnik Surprise

Tyuratam test location for the rocket, October 4, 1957, 22:28 Moscow time.

When a rocket launched from launch pad number one into the nighttime darkness, the sky in Europe was just turning dark and it was still afternoon on the East Coast of the United States. It was one of the greatest products Korolev and his team had created and had proven its effectiveness several times. But this time, the R-7 rocket, often known as “Semyorka” or “digit 7,” was transporting a very unique payload: the first satellite, Sputnik.

The First Satellite From the Reds

Sputnik, the first artificial satellite in Earth orbit, began broadcasting a steady “beep” around five minutes after the launch, which was picked up by Soviet ground station receivers. The Sputnik was really just a glossy aluminum alloy ball, barely 22.8 inches (58 cm) in diameter, and weighing just 184 lbs (83.6 kg).

The satellite was pressurized with nitrogen gas and contained a battery, a radio transmitter broadcasting on different frequencies, a simple fan that activates when internal temperatures reach 97 degrees Fahrenheit (36 degrees Celsius), and a switch that alters the frequency of the radio tones when pressure is lost. There was nothing fancy or original about it. But the world was about to hear the “beep” of the first satellite, sent from far-flung antennae.

Sputnik proved to Korolev and Tikhonravov, two Russian space experts, that their efforts were worthwhile despite widespread doubt and early disappointments. The successful testing of their idea of a strong launch vehicle meant that it might be used to deliver things or even humans into orbit. And now, their hasty choice to proceed with the simpler Sputnik rather than the more sophisticated Object D satellite was paying off. The later test flight of the American launch vehicle Jupiter-C on September 20, 1956, led by Wernher von Braun, proved that the United States had the capability to launch a satellite as well.

A Warning to the USA

Sputnik, on the other hand, was a major surprise to the United States and its Western allies. The Soviet Union demonstrated that it could compete with the technological powerhouse USA with a small beeping metal ball. The allegedly “troubled” communist economy was actually a formidable opponent. Furthermore, the communist adversary now had access to missile technology via the R-7 launch vehicle, possibly putting any nation within its range.

These revelations had shaken the Americans, who were now ramping up their missile development. In order to at least be ahead in the first human space mission, they were consolidating research institutions under the auspices of the recently established NASA and thereby pooling resources. On December 6, 1957, a Vanguard rocket was used to try to send a satellite into orbit. But this effort soon failed. Von Braun did, however, succeed in doing so with the Juno C and Explorer 1 satellites four months later.

Monkeys and Dogs in Outer Space

However, the Soviet Union did not remain content. Korolev and his team had been attempting to convert Sputnik technology for human flight for many years. A dog named “Laika” and a barely altered Sputnik-2 spacecraft launched the first animal into orbit in November 1957.

The USA and the Soviet Union engaged in a tight head-to-head competition with their respective “Mercury” and “Korabl-Sputnik” projects in the years that followed. The Americans were successful in launching two monkeys to suborbital altitudes and returning them safely down to Earth at the end of 1959 and the beginning of 1960. Korolev and his colleagues adopted the dogs “Belka” and “Strelka” in the middle of 1960 and forced them to complete four orbits before returning to Earth. Life support and reentry systems were already present in the “Mercury” and “Korabl-Sputnik” capsules.

Experts on both systems concurred that it was just a matter of time until humans, rather than dogs and monkeys, would be sitting in one of these capsules. But who would be the first?

Choosing the Cosmonauts

West of Moscow, September 3, 1959, an air base.

A group of aspiring pilots sat in the corridor outside a briefing room, the majority of them seeming a little uneasy. The door opened from time to time, and one of them was summoned within. They were aware that it must be related to a significant task or objective. But they were all male, healthy, no older than 30, no taller than 1.75 meters (5.74 feet), and no heavier than 72 kilos (159 lbs). The one-on-one interview was about to determine whether or not they would be selected, for whatever reason.

Unknown Objectives and Duties

The chats had nothing to do with space. Some officers didn’t understand what the experts were trying to convey or why they were here. Others, on the other hand, understood the situation immediately and requested permission to speak with their family. But it was disallowed. The applicants had to make their own decisions without outside assistance since it was a brand-new, top-secret initiative.

After interviews held throughout the western Soviet Union, there were still 200 candidates left out of the original 3,000. The candidates were invited to the Research Center for Aviation Medicine in Moscow for a series of physical and psychological stress tests. The 25-year-old Air Lieutenant Juri (Yuri) Alexejewitsch Gagarin was also one of them. Born in a small town around 93 miles (150 km) west of Moscow, he switched to a piloting career after completing a technical education. He had been employed as a fighter pilot in Murmansk, Alaska, for the last two years.

The test results and the names of the 20 future Soviet cosmonauts were formally announced by the selection committee in February 1960. They also included Yuri Gagarin. His desire, intellect, and dedication left a lasting impression on the Russian examiners.

Gagarin was modest, had a high level of intellectual development, and had an exceptional memory. He distinguished himself from his peers by paying close and thorough attention to his environment. He was also meticulously planning out his activities and training, and he had no trouble with higher mathematics, mathematical formulas, or celestial mechanics. Finally, he seemed to have more practical experience than most of his competitors.

Meanwhile, NASA unveiled the “Mercury Seven,” the organization’s first astronauts, a little over six months earlier than the Russians. In contrast to their Russian counterparts, Alan Shepard, John Glenn, and the others were on average several years older and had at least 1,500 hours of flying experience. At slightly over 200 hours, Yuri Gagarin and many of his colleagues were not all fully qualified test pilots.

However, as proven numerous times in automated flights and those with animals on board, the Russian technology did not need highly competent engineers. At every step of the flight, American astronauts must assist in controlling their rocket systems. The cosmonaut, on the other hand, was mostly just an observer, except when unplanned things happened.

But there was one exception: the manual controls, which were usually locked in flight, could be unlocked by the cosmonaut by inputting a three-digit code. Just before takeoff, cosmonauts would get the code in the form of a sealed envelope, but they could only open it with the explicit permission of the ground station.

The First Test and the Catastrophe at Baikonur

Summer 1960.

The Space Race was progressing more quickly. Both the United States and the Soviet Union had now launched test flights of their rockets and space capsules in quick succession, sometimes with and occasionally without animal passengers. But at the same time, the Cold War was becoming worse. The military, which still formally commanded Korolev, wanted to launch additional surveillance satellites rather than squander time and money on human spaceflight experiments. However, as it was a private organization, NASA was free to focus only on “Project Mercury.”

“Vanguard Six”

The 20 cosmonauts were now being specially trained in Moscow for a voyage into orbit in a spacecraft simulator. However, there was just one test device available for all of them. Korolev and the program’s directors decided to select six cosmonauts to go through expedited training since they were concerned that this bottleneck might cause the program to stall. Once again, exams and interviews were conducted to identify the six “vanguard” members: they included Andriyan Nikolayev, Pavel Popovich, Gherman Titov, Grigory Nelyubov, and Valery Bykovsky, in addition to Yuri Gagarin.

The cosmonauts were making progress, and the most recent test flight of the spacecraft and Vostok launch vehicle was going well. Everything was still on track. Moreover, the program’s directors were recommending that the first cosmonaut launch into space in December 1960. Before that, they just wanted to do one more test flight, but it now seemed too likely that the Americans could overtake the Russians at any moment.

The Nedelin Catastrophe

Around 6:30 p.m. Moscow time on October 24, 1960, at the Tyuratam test site.

On the launch pad, the R-16 military intercontinental ballistic missile was prepared and seemed to be in perfect condition. The control center, however, was the scene of a contentious debate. Because there were issues with the electronics and a fuel leak, and launch preparations were abandoned, the technicians claimed that the rocket was anything but ready for launch. But Mitrofan Nedelin, commander of the Strategic Missile Forces and a special visitor from Moscow, was unwavering. This rocket had to launch in time for the anniversary of the Russian October Revolution for propagandistic purposes.

Nedelin, settling down on a chair a few feet from the rocket, said: “What exactly should I fear? I’m an officer, am I not?” Not wanting to look scared, some 150 other engineers and military personnel decided to stay at the launch site as well. He had scheduled the launch of the R-16 for 7:30 p.m., and there was a little under three-quarters of an hour to go. But a little while later, the unexpected occurred: The second-stage engine caught fire during the test, rupturing the first-stage tanks underneath it, which were packed with highly flammable gasoline, and the whole thing exploded in a massive flame. Nedelin perished along with everyone else on the launch pad.

Vostok Delays

The biggest disaster in the history of rocket science did not spell the end for Korolev’s Vostok program, but rather a definite postponement. Since several other top officials also died in the blast and left the equipment in pieces, nothing occurred for two priceless weeks. But a manned flight would still be feasible, no later than the end of February.

The news from the United States was at least “encouraging.” The first Mercury capsule flight on a “Redstone” launch vehicle failed during liftoff on November 21, 1960. That allowed Korolev and his peers to catch their breath. Then, in December 1960, two consecutive Soviet test flights failed. Due to an engine failure, the first flight, Korabl-Sputnik-3, and the two dogs on board burned up in orbit. The second, Vostok-1K-4, remained in suborbital flight but successfully landed.

Not exactly promising prospects for Yuri Gagarin and his five cosmonaut coworkers.

One Last Run Into Space

Events on both sides of the Iron Curtain reached a boiling point at the start of 1961. The Mercury program was having success after success in the USA. NASA successfully tested the new Atlas launch vehicle and Mercury capsule combo in February after sending the first chimpanzee into space with Mercury-Redstone-2 in January.

However, Sergei Korolev and his colleagues in the Soviet Union were still furiously analyzing the December failures and addressing their causes. It won’t be until March 9 for the subsequent test flight. But if NASA decided to send a human on the next Mercury mission, the Russians would lose everything.

Wernher von Braun, Korolev’s American opponent, stepped in to unknowingly help the Russians. According to von Braun’s engine specialists, one further automated Redstone flight was necessary before a manned space mission. The earliest launch date for a human mission is now set for early May after NASA authorities approved the suggestion.

A Triumph for the Gatekeepers

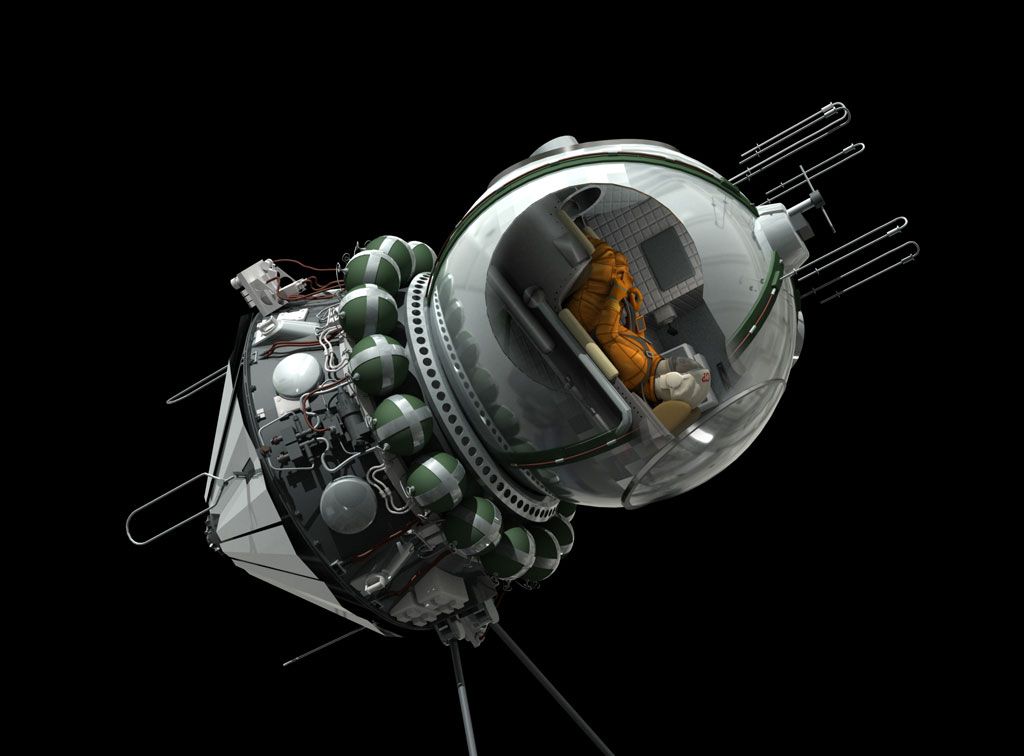

This provided Korolev with the necessary time. On March 9 and 25, 1961, two Korabl-Sputnik missions were simultaneously launched, each carrying a dog and a human dummy. Both went exactly as planned, signaling a significant turning point in the Soviet space program. Gagarin’s mission was made possible by the world’s first crewed spacecraft, Vostok 3KA-2 (or Vostok 1).

Korolev offered “Labor Day” as a potential launch date to Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, the president of the Soviet government. Khrushchev, however, believed that this was too sensitive since he did not want to risk the chance of failure overshadowing the festivities. He offered Korolev the option of starting before or after May 1. Korolev chose to move it up to mid- or late-April since he was under pressure from the Mercury program’s development.

Titov or Gagarin?

The six “vanguard” cosmonauts were now practicing putting on their SK-1 spacesuits and boarding the Vostok spacecraft at Tyuratam. All six remained candidates for a spot on the first Vostok mission. Gherman Titov and Yuri Gagarin, on the other hand, were Nikolai Kamanin’s current two favorites in the cosmonaut training program. Both were outstanding, but over the last few days, more and more people came out in favor of Titov. However, the necessity to utilize a resilient person for the one-day trip was the only thing stopping Nikolai Kamanin from choosing Titov over Gagarin.

On April 9, 1961, Kamanin called the two cosmonauts to his office and informed them of the decision, saying that Titov would serve as Gagarin’s backup on April 12 for the Vostok-1 mission. Titov was given the second trip, which included a full-day flight in addition to the first Earth circumnavigation. Years later, when asked how he felt about the decision, Titov said, “What a question! Painful or not, it was definitely uncomfortable.” Gagarin received all the publicity with the first flight, even though Titov’s assignment was actually by far the most difficult.

Tyuratam Cosmodrome, 11th of April 1961.

It was the night before the launch. The two cosmonauts, Gagarin and Titov, were already sound asleep in their beds in a modest home next to launch pad 1. Sensors on their bodies kept track of each of their vital signs, and pressure sensors in the bed determined if they were sleeping or turning restlessly. They were both sound asleep.

Now, a few hours ago, they received the last set of instructions from the space engineers Konstantin Feoktistov and Boris Rauschenbach. Rauschenbach later recalled, “I looked at Gagarin, and I realized that this boy would wake up the whole world tomorrow.” At the same time, however, I simply could not make myself understand that tomorrow something would happen that the world had not yet experienced, that this lieutenant sitting there in front of us would become the symbol of a new epoch.” But nothing seemed to bother Gagarin himself, and he was just smiling.

Statistically, It’s A Toss-Up

On the other hand, Sergei Korolev did not sleep through the night. He was the chief engineer in charge of the whole program, so he was well aware of the potential pitfalls. In the space capsule Vostok-1 alone, there were 241 vacuum tubes, almost 6,000 transistors, 56 electric motors, 800 relays and switches, and more than 880 connections. The separate components were connected by 9.3 miles (15 km) of cable. A total of 36 more independent propulsion and control units were included aboard the launch vehicle. The mission could be canceled or Yuri Gagarin’s life could be in danger if even one of these components malfunctions.

Korolev was concerned about the third burn stage of the launch vehicle because if it did not ignite, the cosmonaut would crash land somewhere in the vast Southern Ocean near Cape Horn. As the capsule was not designed for a sea landing, it would sink fast, and a recovery in “unfriendly terrain” would be a disaster as well. At least Korolev succeeded in getting the self-destruct feature removed from this flight, unlike the previous test flights. Previously, if it hadn’t been disarmed, the capsule would have detonated 60 hours after landing. Gagarin was also given “proper instructions” on what to do in the event that Western countries recovered him.

Korolev was well aware that the entire situation was a coin toss. Because everything was in need of a lot more testing, but there was not enough time.

What Were the Specifications of the Vostok 1 Spacecraft?

There wasn’t much inside the first spacecraft to carry a human, Vostok 1. There was a tiny panel of switches to the pilot’s left, a tiny viewing port through which to look outside, and a tiny control panel ahead. A modest toilet and a manual control for the Vostok 1 spaceship’s settings were located to the right. Vostok 1’s launch mass was 4,725 kg (10,417 lb), landing mass 2,400 kg (5,290 lb), and diameter 2.30 m (7 ft 6.5 in).

Final Seconds

Tyuratam, April 12, 1961.

The launch pad was already getting ready, while the cosmonauts were still sleeping. The formal announcement of “all set” occurred at 6:00 Moscow time. Before long, the head of the cosmonaut center personally woke up Gagarin and Titov. They had a quick meal and began to get dressed after a last medical check. Titov and Gagarin were helped into the light blue pressure suit, followed by the orange overall. Gagarin’s face wasn’t showing any signs of stress; instead, he seemed happy.

Gagarin entered the spacecraft at 7:10. From this point forward, the radio would be his sole means of communication with Earth. When shutting the access hatch, a screw became stuck, delaying the start of the countdown. Speaking to the cosmonaut inside the capsule were Korolev and Pavel Popovich, who would serve as the “voice” of the ground station in order to maintain communication with Gagarin.

Yuri Gagarin’s pulse was just 64, yet he nevertheless exuded an air of serenity. Gagarin put on his gloves 15 minutes before liftoff and his helmet 5 minutes earlier. The access tower was removed from the rocket at the same moment. Korolev, on the other hand, had experienced a heart attack in the past and now took some sedatives for the launch.

The Takeoff

Tyuratam Cosmodrome, 09:06:57 Moscow time.

The launch was successful. With Yuri Gagarin aboard, the Vostok-1 launched successfully and made its way into space.

Korolev sat in the ground station’s bunker and kept a careful eye on the telemetry data shown on the screen in front of him. If the number five appeared on the screen, this meant everything was going well and the third burn stage was ignited. However, if it was two, then something was wrong. Five started appearing first, as expected, a little under two minutes after the launch. Then, the display abruptly switched to three. But what did this even mean?

While everyone was still transfixedly staring at the TV, the numbers finally returned to five and remained that way, signaling that everything was good and that Gagarin was still on target.

Gagarin was now in space, orbiting around the Earth and unaware of the problems. He enjoyed the view and the abnormal sense of weightlessness: The braking thrusters fired for precisely 40 seconds at 10:25 a.m. to get the capsule ready for re-entry into the atmosphere. It seemed that everything was going as planned. But suddenly something unexpected occurred:

Gagarin is Spinning in Space

The moment the brake jet stopped, there was a sudden shock, and the spacecraft started rotating on its axis very quickly. At least 30 degrees were rotated every second. Gagarin dictated this into his tape recorder since he was not currently in direct communication with the ground station.

Gagarin waited for separation while pondering what was happening. There was no separation. The instrument module was planned to be launched from the landing capsule exactly 12 seconds after the ignition of the brakes. The metal clamps had to be opened, but a few electric wires were keeping the two together. It was not until 10 minutes later that the frictional heat of the upper atmosphere burned through the wires, barely in time to avert a deadly fall on re-entry.

Gagarin was the first human to see the phenomenon of an object entering the Earth’s atmosphere, and he described it as follows: “Suddenly, a bright, violet glow appeared at the edges and also in the small opening of the right porthole. I felt the movements of the spacecraft and the burning of the coating. I heard cracking sounds. “I felt the temperature was very high.” Gagarin was temporarily subjected to up to 10 g when the spacecraft’s increasing pressure forced him into his seat while he was still reeling: “There was a moment of about three seconds when the instrument readouts blurred before my eyes. “My vision went gray.”

Yuri Gagarin Has Landed

At 22,300 feet (7,000 meters) above the Earth’s surface, on April 12, 1961, at 10:50 am, Gagarin’s Vostok-1 began preparing for its landing. The primary parachute deployed as the capsule decelerated. Gagarin was launched out of the capsule with his ejection seat a few seconds after the hatch was removed. To complete the journey from takeoff to touchdown, the total flight lasted 108 minutes.

While on the phone with Khrushchev, Korolev could be heard saying, “The parachute has opened; he is landing!” Khrushchev excitedly asked back, “Is he alive? Is he sending signals? “Is he alive?” Gagarin, in the meantime, had just separated from his seat, and he was descending on his parachute gently toward the Earth. Below him, something seemed quite familiar:

“I recognized the railroad line, a railroad bridge over the river, and a long strip of land reaching into the Volga. […] I landed in Saratov.” The cosmonauts had already made a number of practice jumps in this vicinity. Gagarin landed in a field close to the town of Smelovka just before 11:00 a.m., although it took him almost five minutes to remove his spacesuit. I climbed up a small hill and saw a woman with a child walking toward me. “I went to her and asked where I could find a telephone,” Gagarin said. His biggest concern right now was to report his successful and safe landing.

When the wonderful news reached Tyuratam, Sergei Korolev seemed to have lost all anxiety. He felt both relieved and validated at this moment, since he had sent the first man into space against all odds. And even into orbit, rather than just on a straight ballistic trajectory, as the Americans had planned.

Korolev worked on the Soviet N-1 lunar rocket’s development in the years that followed, but he passed away from heart failure in 1966 while undergoing surgery. His funeral made his contribution to Soviet spaceflight public in the West for the first time.

Gagarin Was to Be Remembered

On the other hand, April 12, 1961, was a painful day for Wernher von Braun in the United States, who had been Korolev’s longstanding rival. He had lost the Space Race to Korolev. Nobody was interested in the fact that this only occurred by a small margin. As a result, instead of the American Alan Shepard, who became the second man in space in the Mercury-Redstone 4 on May 5, 1961, only the Russian Yuri Gagarin was to be remembered in history books. Just under a year after Yuri Gagarin’s space voyage, in February 1962, John Glenn became the first American astronaut to reach orbit.

Yuri Gagarin himself continued to be a cosmonaut, but during the next several years, he was sent on global publicity tours. He died on March 27, 1968, when his fighter jet crashed while he was on a training mission.

Bibliography:

- Burgess, Colin, 1947, “The first Soviet cosmonaut team : their lives, legacy, and historical impact“.

- Andrew Jenks, 2012, “Conquering space: the cult of Yuri Gagarin“ .

- Francis French, 2010. “Yuri Gagarin: the first person into space (1934–1968)”

- Rex D. Hall, David J. Shayler & Bert Vis, 2007. “Russia’s Cosmonauts: Inside the Yuri Gagarin Training Center“

- New York: Crosscurrents Press, 1961, “First man in space“.