What Does the Word “Inquisition” Mean, and Who Invented It?

The word “inquisition” comes from the Latin word inquisitio, which means “investigation,” “inquiry,” or “search.” We know the Inquisition as a church institution, but initially, this term referred to a type of criminal process. Unlike an accusation (accusatio) or denunciation (denunciatio), where a case was initiated as a result of an open accusation or a secret denunciation, in the case of inquisitio, the court itself started the process based on known suspicions and requested confirming information from the population. This term was coined by lawyers in the late Roman Empire and became established in the Middle Ages in connection with the reception, that is, the discovery, study, and assimilation in the 12th century, of the main monuments of Roman law.

- What Does the Word “Inquisition” Mean, and Who Invented It?

- Why Is It Called “Holy”?

- Who Became Inquisitors, and to Whom Were They Subordinate?

- Where Did the Inquisition Exist?

- Why Is the Spanish Inquisition the Most Famous?

- Who Were They Hunting, and How Was It Determined Who to Execute?

- Why Were Witches Hunted?

- Why Did the Inquisition Torture People?

- Could Inquisitors Accuse a King or, for Example, a Cardinal?

- Did Witches Really Exist, or Were They Just Burning Beautiful Women?

- Why Were Witches Burned?

- Is It True That the Accused Were Constantly Tortured Until They Confessed?

- How Many People Were Burned in Total?

- How Did Ordinary People View the Inquisition?

- When Did the Inquisition End?

Judicial investigations were practiced by both the royal court — for example, in England — and the Church, in their fight not only against heresy but also against other crimes within the jurisdiction of ecclesiastical courts, including fornication and bigamy. However, the most powerful, stable, and well-known form of church inquisitio became inquisitio hereticae pravitatis, or the search for heretical depravity. In this sense, the term “inquisition” was invented by Pope Lucius III, who, at the end of the 12th century, obliged bishops to search for heretics by traveling around their diocese several times a year and questioning trustworthy local residents about the suspicious behavior of their neighbors.

Why Is It Called “Holy”?

The Inquisition was not always and everywhere called “holy.” This epithet does not appear in the term “search for heretical depravity,” nor in the official name of the highest body of the Spanish Inquisition — the Council of the Supreme and General Inquisition. The central authority of the papal Inquisition, established during the reform of the papal curia in the mid-16th century, was indeed called the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition. However, the word “sacred” was similarly included in the full names of other congregations or departments of the curia — for example, the Sacred Congregation of Rites or the Sacred Congregation of the Index.

At the same time, in common usage and in various documents, the Inquisition began to be called Sanctum Officium — in Spain, Santo Oficio — which translates as “holy office,” or “department,” or “service.” In the first half of the 20th century, this phrase entered the name of the Roman congregation, and in this context, the epithet does not cause surprise: the Inquisition was subordinated to the Holy See and was engaged in the protection of the holy Catholic faith, a mission that was considered not just holy but almost divine.

For example, the first historian of the Inquisition, himself a Sicilian inquisitor — Luis de Paramo — began the history of religious investigation with the expulsion from Paradise, making God himself the first inquisitor: he investigated the sin of Adam and punished him accordingly.

Who Became Inquisitors, and to Whom Were They Subordinate?

Initially, for several decades, the popes tried to entrust the Inquisition to the bishops and even threatened to remove those who were negligent in cleansing their dioceses of heretical contagion. However, the bishops were not well-suited to this task: they were busy with their routine duties, and, more importantly, their efforts to combat heresy were hindered by established social ties, primarily with the local nobility, who sometimes openly supported the heretics. Thus, in the early 1230s, the pope entrusted the search for heretics to monks of the mendicant orders — Dominicans and Franciscans.

They had several qualities necessary for this work: they were loyal to the pope, independent of local clergy and lords, and popular among the people for their demonstrative poverty and asceticism. The monks competed with heretical preachers and ensured public cooperation in the search for heretics. Inquisitors were given extensive powers and were independent of local ecclesiastical authorities or papal legates. They were directly subordinate only to the pope, held their powers for life, and in any force majeure situations, could travel to Rome to appeal to the pope. Moreover, inquisitors could justify each other, making it almost impossible to remove an inquisitor, let alone excommunicate them from the Church.

Where Did the Inquisition Exist?

The Inquisition — episcopal from the late 12th century and papal, or Dominican, from the 1230s — appeared in southern France. Around the same time, it was introduced in the neighboring Crown of Aragon. In both places, the problem was the eradication of the Cathar heresy: this dualistic doctrine, which came from the Balkans and spread across much of Western Europe, was especially popular on both sides of the Pyrenees.

After the anti-heretical Crusade of 1215, the Cathars went underground, and the sword proved ineffective; what was needed was the long and tenacious hand of the church investigation.

Throughout the 13th century, at the papal initiative, the Inquisition was introduced in various Italian states: in Lombardy and Genoa, the Inquisition was managed by the Dominicans, while in Central and Southern Italy, the Franciscans were in charge. Towards the end of the century, the Inquisition was established in the Kingdom of Naples, Sicily, and Venice. In the 16th century, during the Counter-Reformation, the Italian Inquisition, led by the first congregation of the papal curia, gained new momentum in combating Protestants and various free-thinkers.

In the German Empire, Dominican inquisitors operated from time to time, but there were no permanent tribunals due to the centuries-long conflict between emperors and popes and the administrative fragmentation of the empire, which made any initiatives at the state level difficult. In the Czech Republic, there was an episcopal Inquisition, but it was not particularly effective — at least in eradicating the heresy of the Hussites, followers of Jan Hus, the Czech Church reformer burned in 1415, they had to send specialists from Italy.

At the end of the 15th century, a new, or royal, Inquisition emerged in unified Spain — first in Castile and then again in Aragon. In the early 16th century, it appeared in Portugal, and in the 1570s, in the colonies — Peru, Mexico, Brazil, and Goa.

Why Is the Spanish Inquisition the Most Famous?

Probably because of its negative publicity. The fact is that the Inquisition became a central element of the so-called “black legend” of Habsburg Spain as a backward and obscurantist country, ruled by arrogant nobles and fanatical Dominicans. The “black legend” was spread by both political opponents of the Habsburgs and the victims — or potential victims — of the Inquisition.

Among them were converted Jews — Marranos, who emigrated from the Iberian Peninsula, for example, to the Netherlands, where they cultivated the memory of their fellow martyrs of the Inquisition; Spanish Protestant emigrants and foreign Protestants; residents of non-Spanish possessions of the Spanish crown: Sicily, Naples, the Netherlands, and England during the marriage of Mary Tudor and Philip II, who either resented the introduction of the Inquisition by the Spanish model or only feared it; and French Enlightenment thinkers, who saw the Inquisition as the embodiment of medieval obscurantism and Catholic domination.

All of them, in their numerous writings — from newspaper pamphlets to historical treatises — worked long and hard to create the image of the Spanish Inquisition as a terrible monster threatening all of Europe.

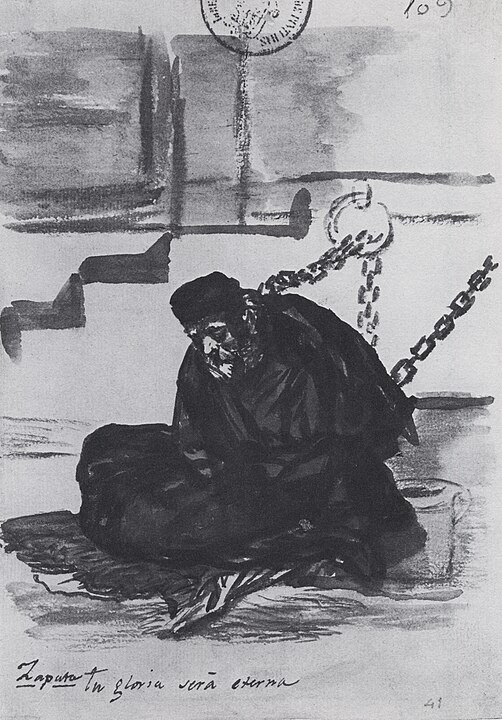

Finally, by the end of the 19th century, after the abolition of the Inquisition and during the collapse of the colonial empire and deep crisis in the country, the demonic image of the Holy Office was adopted by the Spaniards themselves, who began to blame the Inquisition for all their problems.

The conservative Catholic thinker Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo parodied this line of liberal thought: “Why is there no industry in Spain? Because of the Inquisition. Why are Spaniards lazy? Because of the Inquisition. Why the siesta? Because of the Inquisition. Why the bullfight? Because of the Inquisition.”

Who Were They Hunting, and How Was It Determined Who to Execute?

At different times and in different countries, the Inquisition was interested in different groups of people. What united them was that they all, in one way or another, deviated from the Catholic faith, thereby damaging their souls and causing “harm and insult” to this very faith. In southern France, these were the Cathars, or Albigensians; in the north, the Waldensians, or Lyonese Poor, another anticlerical heresy striving for apostolic poverty and righteousness.

In addition, the French Inquisition persecuted Jewish converts who returned to Judaism and Spirituals — radical Franciscans who took the vow of poverty seriously and were critical of the Church. Sometimes the Inquisition was involved in political cases like the trial of the Knights Templar, accused of heresy and worshiping the devil, or Joan of Arc, accused of roughly the same; in reality, both represented a political obstacle or threat to the king and the English occupiers, respectively. In Italy, there were Cathars, Waldensians, and Spirituals; later, the heresy of the Dolcinists, or Apostolic Brethren, was persecuted. During the Counter-Reformation, they sought out various types of reformers, from the real Protestants who joined Luther and Calvin to the German merchants in Venice who smuggled heretical literature into Italy.

The Spanish Inquisition initially opposed the conversos, descendants of converted Jews who were suspected of continuing to practice their former religion in secret. Later, the Inquisition spread to the Moriscos, converts from Islam. In the 16th century, it hunted Protestants and various free-thinkers, including the supporters of Erasmus of Rotterdam. In the 17th century, it prosecuted Jews who migrated from Portugal to Spain and those who were only accused of Judaizing. In the 18th century, it focused on enlightened intellectuals and secret societies like the Masons.

In the New World, the tribunals hunted conversos — mainly immigrants from Portugal — and Protestant foreigners.

The Inquisition identified its suspects in several ways. There were public confessions — an annual ceremony of denunciation — and regular purges of monasteries. There were denunciations by neighbors and hired informants who received a percentage of the confiscated property or even a salary. There were also denunciations by slaves against their masters, and vice versa, denunciations in the Inquisition could only be canceled by another denunciation. Inquisitors themselves traveled around the country, summoning people for interviews and interrogations. Finally, inquisitors read books and decided whether to initiate a trial based on what they found.

Why Were Witches Hunted?

At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, there was a strong belief in the existence of a secret conspiracy of witches that arose in society — first in the areas most affected by the religious wars of the 16th century, then in other parts of Europe. It was believed that witches and sorcerers made pacts with the devil and periodically gathered at witches’ sabbaths to have orgies, kill and eat babies, and commit other atrocities. Against the backdrop of the rising Protestant and Catholic Reformation, the secular and ecclesiastical authorities simultaneously felt the need for uncompromising methods to restore and maintain order — hence the hunt for witches.

Interestingly, the witch hunt was carried out primarily by secular authorities; the Inquisition, although not opposed to persecuting witches, was more interested in combating heresy and did not have the same fervor or resources for a mass hunt. The Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions were generally skeptical of witches and sorcerers, considering many of the accusations to be exaggerations.

Moreover, in several cases, inquisitors opposed the local authorities, who were eager to execute witches. For example, in 1610, the Spanish Inquisition intervened in the witch trials in the Basque region, where local officials had already executed several people. The inquisitors argued that there was insufficient evidence and released most of the suspects.

Why Did the Inquisition Torture People?

Torture was used to obtain confessions from suspects. The justification for using torture was based on the Roman legal tradition, where it was an accepted practice for extracting confessions in cases of serious crimes. The medieval Inquisition adopted this practice, considering heresy to be a severe crime that endangered both the individual soul and the Christian community. The Inquisition believed that it was better to extract a confession under torture to save the soul of the accused, who might otherwise be condemned to eternal damnation.

However, the use of torture by the Inquisition was regulated by a set of rules. Torture could not be applied without sufficient evidence or indications of guilt, and it could not be used repeatedly on the same individual. Moreover, the torture methods were generally less severe than those used by secular authorities at the time. The Inquisition was also concerned with the possibility of false confessions obtained under torture, so it often sought corroborating evidence before proceeding with punishment.

While the use of torture by the Inquisition is often highlighted in historical accounts, it is essential to note that it was a common practice in many judicial systems during the Middle Ages and the early modern period, both secular and religious.

Could Inquisitors Accuse a King or, for Example, a Cardinal?

Everyone was subject to the Inquisition: in cases of suspicion of heresy, the immunity of monarchs or church hierarchs did not apply. However, only the Pope himself could convict people of such a rank. There are known cases of high-ranking defendants appealing to the Pope and attempting to remove their case from the jurisdiction of the Inquisition.

For example, Don Sancho de la Caballería, an Aragonese grandee of Jewish origin known for his hostility toward the Inquisition, which violated noble immunities, was arrested on charges of sodomy. He enlisted the support of the Archbishop of Zaragoza and complained about the Aragonese Inquisition to the Suprema — the supreme council of the Spanish Inquisition, and then to Rome.

Don Sancho insisted that sodomy did not fall under the jurisdiction of the Inquisition and tried to transfer his case to the Archbishop’s court, but the Inquisition had received appropriate authority from the Pope and would not release him. The trial lasted several years and ended in nothing — Don Sancho died in confinement.

Did Witches Really Exist, or Were They Just Burning Beautiful Women?

The question of the reality of witchcraft obviously goes beyond the historian’s competence.

Let’s put it this way: many — both the persecutors and the victims, and their contemporaries — believed in the reality and effectiveness of sorcery. Renaissance misogyny considered it a typically female activity. The most famous anti-witchcraft treatise, “The Malleus Maleficarum” (“Hammer of Witches”), explains that women are overly emotional and not sufficiently rational. Firstly, they often deviate from faith and succumb to the devil’s influence, and secondly, they easily get involved in quarrels and brawls, and due to their physical and legal weakness, resort to witchcraft for protection.

Women were not necessarily “appointed” as witches simply because they were young and beautiful, though young and beautiful women were also targeted — in such cases, the accusation of witchcraft often reflected men’s (particularly monks’) fear of female allure. Elderly midwives and healers were also accused of consorting with the devil, likely due to the clergy’s fear of their unfamiliar knowledge and the influence these women held in their communities. Furthermore, single and poor women — the most vulnerable members of society — were frequently accused of witchcraft.

According to the theory of British anthropologist Alan Macfarlane, witch hunts in England during the Tudor and Stuart periods (16th–17th centuries) were driven by social changes, such as the breakdown of traditional communities, rising individualism, and increasing economic inequality in rural areas. Wealthy individuals, seeking to justify their prosperity amidst the poverty of their neighbors — particularly single women — began accusing them of witchcraft. The witch hunts thus served as a means of managing communal conflicts and alleviating social tensions.

In contrast, the Spanish Inquisition pursued witches far less frequently. Instead, “new Christians” often became scapegoats, especially “new Christian women,” who were sometimes accused of quarrelsomeness or witchcraft in addition to Judaizing.

Why Were Witches Burned?

The Church, as is known, should not shed blood; therefore, burning after strangulation seemed preferable. Moreover, it illustrated the Gospel verse: “If anyone does not remain in Me, he is thrown away like a branch and withers; such branches are gathered, thrown into the fire, and burned.” In reality, the Inquisition did not carry out executions themselves but “handed over” unrepentant heretics to the secular authorities. According to secular laws adopted in Italy and then in Germany and France during the 13th century, heresy was punishable by loss of rights, confiscation of property, and burning at the stake.

Is It True That the Accused Were Constantly Tortured Until They Confessed?

There was some truth to this. Although canon law prohibited the use of torture in ecclesiastical court proceedings, in the mid-13th century, Pope Innocent IV legitimized torture in the investigation of heresy through a special bull, equating heretics with robbers who were tortured in secular courts. As we have said, the Church should not shed blood, and inflicting severe injuries was also forbidden, so methods of torture were chosen that involved stretching the body and tearing muscles, crushing certain parts of the body, breaking joints, as well as torture with water, fire, and red-hot iron. Torture was allowed to be applied only once, but this rule was circumvented by declaring each new torture a continuation of the previous one.

How Many People Were Burned in Total?

Apparently, not as many as one might think, but it is difficult to calculate the number of victims. Speaking of the Spanish Inquisition, its first historian, Juan Antonio Llorente, who was himself the general secretary of the Madrid Inquisition, calculated that in over three centuries of its existence, the Holy Office accused 340,000 people and sent 30,000 to be burned — about 10%. These figures have been revised many times, mainly downward.

Statistical research is complicated by the fact that tribunal archives were damaged, not all have survived, and only partially. The Suprema archive, with reports on cases reviewed by all tribunals sent annually, is better preserved. Usually, data are available for some tribunals over specific periods, and these data are extrapolated to other tribunals and other times. However, this reduces accuracy because the level of severity likely decreased over time.

Based on reports sent to the Suprema, it is estimated that from the mid-16th to the end of the 17th century, inquisitors in Castile and Aragon, Sicily and Sardinia, Peru and Mexico considered 45,000 cases and burned at least 1,500 people — about 3%, but half of them in effigy. “At least” because information for many tribunals is available only for part of this period, but one can form an idea of the scale.

Even if this figure is doubled and it is assumed that in the first 60 and last 130 years of its activity, the Inquisition killed as many, it would still be far from the 30,000 named by Llorente.

The Roman Inquisition of the early modern period is believed to have considered 50,000–70,000 cases and executed around 1,300 people. Witch hunts were more destructive — with several tens of thousands burned. But in general, inquisitors tried to “reconcile” rather than “hand over.”

How Did Ordinary People View the Inquisition?

Critics of the Inquisition, of course, believed that it enslaved the people, binding them with fear, while the people, in turn, hated it. “In Spain, where fear muted voices, / Ruled Ferdinand and Isabella, / And the Grand Inquisitor reigned with an iron hand over the land,” wrote American poet Henry Longfellow.

Modern revisionist researchers refute such a view of the Inquisition, including the idea of violence against the Spanish people, pointing out that in terms of its bloodthirstiness, it was noticeably inferior to German and English secular courts dealing with heretics and witches, or French persecutors of Huguenots, and also that the Spanish themselves never seemed to have anything against the Inquisition until the Revolution of 1820.

There are known cases where people tried to bring themselves under its jurisdiction, considering it preferable to the secular court, and indeed, if you look at cases not involving Marranos and Moriscos, but “Old Christians” from among the common people accused, for example, of blasphemy out of ignorance, coarseness, or drunkenness, the punishments were relatively mild: a number of lashes, expulsion from the diocese for several years, imprisonment in a monastery.

When Did the Inquisition End?

It hasn’t really ended — it just changed its name. The Congregation of the Inquisition (in the first half of the 20th century — the Congregation of the Holy Office) was renamed the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith at the Second Vatican Council in 1965, and it still exists today, dealing with the protection of faith and morality among Catholics, in particular investigating sexual crimes by clergy and censoring works by Catholic theologians that contradict Church doctrine.

As for the Spanish Inquisition, its activity declined in the 18th century, and it was abolished in 1808 by Joseph Bonaparte. During the restoration of the Spanish Bourbons after the French occupation, it was reinstated, abolished during the “Trienio Liberal” of 1820–1823, reinstated again by the king returned on French bayonets, and finally abolished in 1834.