Desiderius (Died 607)

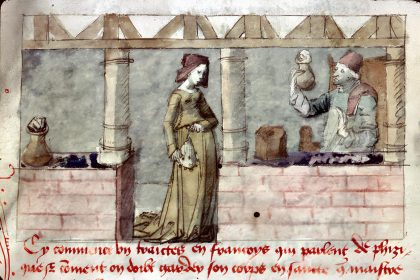

Desiderius, Archbishop of Vienne, was not only a well-educated man but also a righteous one. However, because he advocated for teaching grammar based on secular literature, the church authorities accused him of an inappropriate love for pagan poets. Additionally, Desiderius openly condemned what he saw as the debauched lifestyles of King Theuderic II, his grandmother Queen Brunhilda, and other secular authorities.

The archbishop’s real troubles began after he quarreled with Prothadius, an official with connections to the royal family (it is believed that Prothadius was the lover of the elderly queen). In 603, a noblewoman named Justa, one of the parishioners, suddenly accused Desiderius of rape. Not long before, several similar scandals had erupted in the Frankish kingdoms, and Vienne was the capital of their religious life, so Queen Brunhilda could not ignore this case. Desiderius did not deny his guilt or comment on the incident at all, yet historians believe the accusation was completely fabricated.

A church council was convened to judge Desiderius. The case was examined in Cabillonum (modern-day Chalon-sur-Saône), the royal residence of Burgundy. The presiding bishop was Aredius of Lyon, who did not like Desiderius. In the presence of King Theuderic II and Queen Brunhilda, the council quickly found the archbishop guilty and sentenced him to removal from office, deprivation of civil rights, and exile to a monastery on the island of Lérins.

Four years later, Prothadius died, and doubts were raised about the truthfulness of the accusations against Desiderius. Theuderic and Brunhilda restored the exiled archbishop to his post — but not for long. Desiderius again turned the queen against him, was arrested, and taken to a village near Lyon (which still bears his name). There, royal soldiers, without trial or investigation, beat him to death. Later, the church canonized Desiderius.

Conradin (1252–1268)

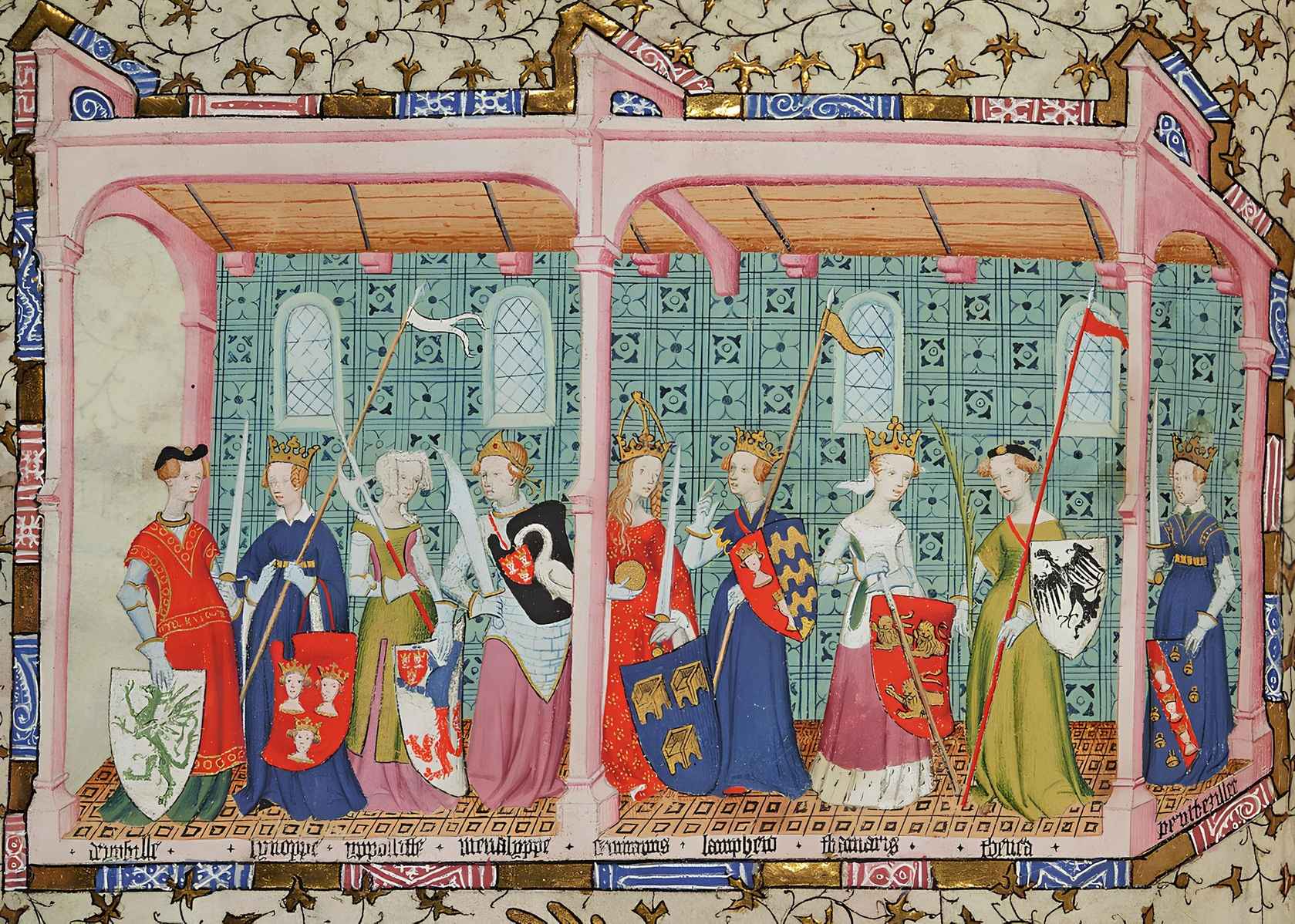

Conradin, Duke of Swabia, King of Jerusalem, and Sicily, lost his father at the age of two and inherited the throne. In Sicily, his father’s brother, Manfred, became regent. Upon receiving a false report of his nephew’s death, Manfred declared himself king. When it was revealed that Conradin was still alive, he decided not to return the throne to his nephew but promised to make him his heir.

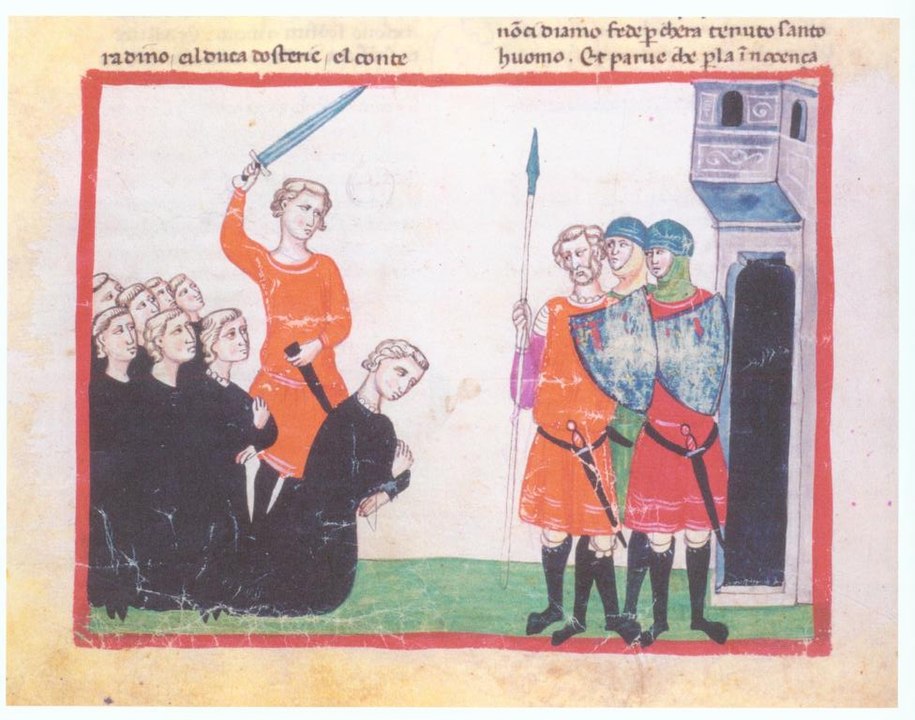

Meanwhile, Pope Clement IV did not recognize the right to Sicily for either of them and blessed Charles I of Anjou to the throne. Charles defeated Manfred’s forces and took possession of the Kingdom of Sicily. Then, Conradin, who was already fifteen years old, won several important battles, but his army was eventually defeated, and he was captured. Most of his supporters were immediately executed, while Conradin and his close associate, Frederick of Baden, were taken to Charles in Naples to be executed following a court ruling.

In Naples, a public and allegedly impartial hearing was organized, where the prosecution’s lawyers presented Conradin’s invasion as an act of treason and robbery. They argued that the accused had gone against the Pope, resulting in the deaths of civilians in the area of Tagliacozzo (an Italian town near the site of Conradin’s decisive battle), which was outside the disputed territory of Sicily. They characterized these deaths as murders and crimes against divine and human laws.

The defense was represented by a Neapolitan lawyer who claimed that Conradin was the legitimate heir to the throne, and thus his actions should not be seen as defiance of the Pope’s will or as aggression. As for the civilian deaths, he argued they were the result of a military conflict, and Conradin should not be held responsible.

Ultimately, four judges found Conradin guilty, adding the charge of insulting the Pope, for which Conradin was first excommunicated. Additionally, the court sentenced Conradin and Frederick of Baden to death. The execution was carried out in 1268: Conradin and several of his associates were beheaded. This execution shocked all of Europe. Conradin was later mentioned as an innocent victim by Dante and Heinrich Heine.

Jacques de Molay (1244–1314)

In the early 14th century, rumors spread throughout France that the Templars, members of one of the largest and wealthiest military-monastic orders, were forcing new members during initiation to spit on the cross, worship idols, encourage “unnatural lust,” and commit other indecencies and blasphemies. Jacques de Molay, the 23rd and last Grand Master of the order, first appealed to King Philip the Fair and then to Pope Clement V to investigate the defamatory rumors about the order.

Both promised to comply with his request, but instead, the king secretly instructed his officials to begin mass arrests of Templars. De Molay was among those arrested. The order’s property was confiscated and added to the royal treasury. Furthermore, Philip sent letters to other European monarchs demanding the extradition of knights who were outside France.

At first, they refused, but after the Pope, who was trying to lead the persecution of the Templars, issued a bull essentially requiring compliance with the king’s request, they handed over a few people.

This was followed by a lengthy trial during which the original five charges grew to an unprecedented number.

During the investigation, the defendants were subjected to the harshest torture, explaining why Molay changed his testimony several times. In October 1307, he admitted that there was indeed a custom in the order to renounce Christ and spit on the cross. He wrote a letter to the members of the order, urging them to follow his example and confess to the offenses described in the letter; many knights followed his advice. But at the first hearing held by the papal commission, Molay recanted his testimony, and Clement V suspended the investigation.

Soon, Philip forced the Pope to reopen the hearings. The process was now divided into two parts: the papal court dealt with the cases of individual members, while the fate of the order as a whole was to be determined by a specially convened Council of Vienne. In August 1308, Molay was interrogated again, this time in the presence of royal agents, and returned to his confessional statements, but in 1309, before the papal commission, he denied the charges against the order.

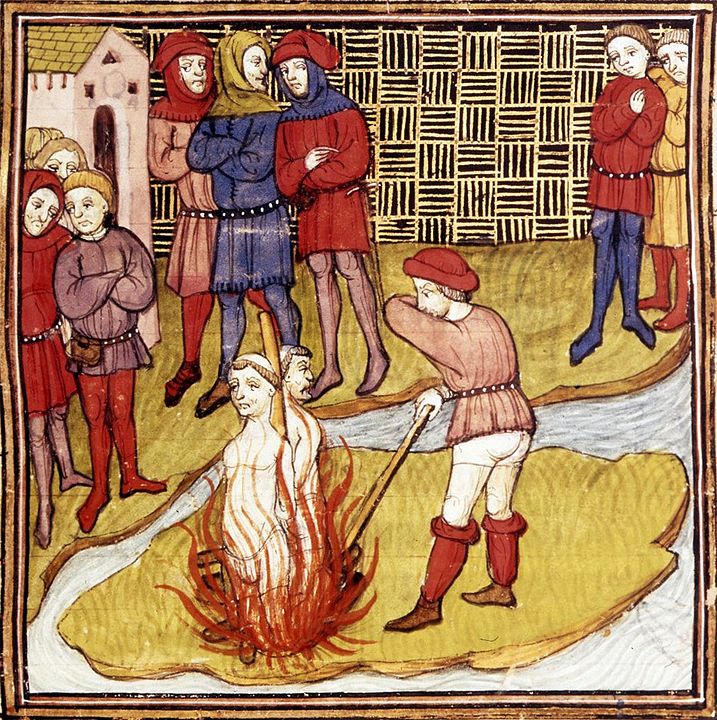

Other members of the order began to join him, claiming that their confessions had been extracted under torture. In response, Philip IV executed 54 knights of the order, burning them at the stake as relapsed heretics. In 1312, the Pope finally dissolved the order.

The hearings continued for another two years. Finally, Molay and his closest associates were sentenced to life imprisonment. Most Templars listened to the verdict in silence, but Molay and a member of the order, Geoffrey de Charney, declared that they were guilty not of what they were accused of, but of renouncing the order in an attempt to save their lives. The Grand Master stated that the order was holy and innocent. This enraged Philip. Molay was swiftly condemned and burned at the stake as a heretic without further investigation. Before his execution, he was offered a quicker death if he confessed his guilt, but he refused.

William Wallace (1270–1305)

In 1296, King Edward I of England proclaimed himself King of Scotland. The following year marked the beginning of the First War of Scottish Independence. The war began with the murder of the English sheriff of Lanark by William Wallace, a member of the lower Scottish nobility. According to legend, Wallace was avenging his wife’s death. The war gradually spread throughout Scotland, and the Scottish nobility began to join the rebels. The struggle proceeded with varying success, and at one point, only a few castles remained in English hands.

However, in 1305, Wallace was captured near Glasgow and taken to London.

His trial took place in Westminster, presided over by King Edward I of England himself. Wallace was accused of treason, the murders of royal officials and civilians, sacrilege, and the burning of churches and relics. He was not allowed to defend himself; instead, he had to silently listen to the full list of actions for which he was blamed. Nevertheless, in response to the accusations, he uttered the famous phrase that he could not be a traitor because he had never been Edward’s subject nor sworn allegiance to him.

This remark, essentially true, changed nothing: in front of a large crowd, it was announced that Wallace was sentenced to the punishment reserved for all traitors to the crown. He was tied to a horse and dragged through the streets from the Tower to Smithfield, the execution ground in London. There, he was hanged, drawn, and quartered, and his head was cut off. Parts of his body were displayed in major Scottish cities to intimidate their inhabitants.

John Ball (1330–1381)

The English priest John Ball preached social equality and sympathized with the emerging ideas of Protestantism. Due to his radical views, he was repeatedly imprisoned for heresy. At one point, the Archbishop of Canterbury even banned him from speaking and forbade the congregation from listening to his sermons, apparently excommunicating him from the church. However, this did not stop Ball; he became a wandering preacher without a parish and continued to enjoy popularity among the public.

In the spring of 1381, the first major peasant uprising began, led by a village craftsman named Wat Tyler. According to one version, at this time Ball was once again in prison, where he was to remain for three months, but was freed by the rebels. The preacher then joined the uprising and became its ideological leader, proclaiming that slavery was unnatural because all people are born equal, and therefore, serfdom in England should be abolished. In his most famous sermon, he said, “When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?”

By the summer, the rebellion had reached London. The young King Richard II, concerned by the scale of the revolt, sought to appease the rebels, assuring them that he would meet their demands. However, during one of his meetings with Tyler, the latter was killed. Deprived of their leader, the rebellion gradually subsided.

The peasants, trusting the king’s promises, dispersed and returned home.

After this, John Ball was arrested and brought to trial the very next day. Many of the rebels were merely fined or given short prison sentences. However, Ball, who at the trial did not deny the charges against him, refused to renounce his ideas, express regret, or show any doubt in his actions, fully acknowledging his authorship of the speeches and letters, was sentenced to death as a traitor. In the presence of King Richard II, he was hanged, drawn, and quartered, and his head was displayed on London Bridge as a reminder of the fate that awaits rebels.

Girolamo Savonarola (1452–1498)

At the height of humanism, with its cult of classical literature, pursuit of spiritual pleasures, and proclaimed freedom of human will, Savonarola, a Florentine Dominican priest, delivered sermons at the church of San Marco, denouncing vice and predicting divine punishment that would befall Italy for its sins. He openly criticized Lorenzo de’ Medici, the ruler of Florence, and later his son Piero the Unfortunate, accusing them of debauchery, lack of piety, and passion for luxury. He also spoke out against the Pope and prelates who were excessively fond of Greek poetry and the arts.

Savonarola became an extraordinarily influential preacher. He claimed that God’s words descended directly to him from heaven, thus placing himself on par with Old Testament prophets. His credibility was strengthened after several of his prophecies came true.

In 1494, the French King Charles VIII invaded Italy and ousted Piero de’ Medici. Savonarola became the de facto ruler of Florence and began its purification. He reformed the governance of the republic and punished impious citizens—fashionistas, gamblers, blasphemers, and the depraved. In February 1497, a massive “Bonfire of the Vanities” took place in the city, in which expensive clothes, mirrors, playing cards, books, musical instruments, paintings, and sculptures were burned—several of Botticelli’s works are believed to have been burned in this fire.

During his fanatical activities and uncompromising sermons, Savonarola made many enemies. In May 1497, Pope Alexander VI excommunicated Savonarola from the church and demanded that the Florentine authorities either imprison him immediately or send him to Rome, threatening Florence with a ban on religious rites if they disobeyed and excommunicating anyone who listened to the priest.

Eventually, under pressure from Rome, the city authorities banned Savonarola from preaching. In response, the priest wrote a letter to Charles VIII, proposing to depose the Pope, but the letter never reached the king as it was intercepted and delivered to the Pope himself.

Savonarola was challenged to prove his righteousness through an ordeal: he and a Franciscan monk were to pass through several fires—it was assumed that the one on God’s side would remain unharmed. Without notifying Savonarola, one of his followers volunteered to undergo the ordeal. On the day of the test, the whole city gathered in the square, but rain prevented the ordeal from taking place. The absence of the promised miracle and the fact that another person was to undergo the trial instead of Savonarola led to a loss of popular support. He had to take refuge from the angry crowd in the monastery of San Marco. The next day, the crowd besieged the monastery, and, choosing between the enraged people and the authorities, Savonarola chose the latter.

Contrary to the Pope’s wishes, the trial took place not in Rome, but in Florence. However, the Pope established a special commission of seventeen of Savonarola’s opponents to review the case. During the investigation, he was subjected to torture fourteen times a day, during which he repeatedly confessed that all his teachings, visions, and sermons were false, but as soon as the torture stopped, he retracted his words. This could not serve as convincing evidence, so the defendant’s testimony was eventually falsified and published in a more consistent form. The court sentenced him to death. Before a large crowd, Savonarola and his followers were hanged, and their bodies were then burned. Two centuries later, the church exonerated Savonarola, and today there is discussion about his canonization.