The German Campaign of 1813 was led by Napoleon Bonaparte from April to October 1813 against the armies of the Sixth Coalition. Like a phoenix rising from its ashes, the Grande Armée, which had disappeared in the snows of Russia in 1812, suddenly seemed to be reborn in the plains of Saxony. The Russians saw their march on Paris abruptly halted by the resurgence of the French Empire: thousands of young conscripts blocked their path, led by the greatest general of the time. However, victories were not enough in the face of shifting alliances, with Prussia, Austria, and numerous German states turning against Napoleon.

Context of the 1813 Campaign

The elite of the Grande Armée had been lost during the disastrous Russian campaign, falling victim to both the Russian army and, more so, the harsh winter and diseases. In France, the attempted coup by General Malet had forced the Emperor to return hastily by sled. Marshal Joachim Murat, whom Napoleon had entrusted with command of the army, abandoned his post to return to his Kingdom of Naples, leaving Eugène de Beauharnais to take command of the retreating troops.

Upon returning to Paris, Napoleon reasserted his power and made every effort to rebuild an army capable of halting the Russian advance. He organized mass conscriptions in France, enlisting young, inexperienced men aged 17 to 18, who were sent quickly to the Rhine before they could receive proper military training. These 1813 levies gave rise to the image of the ogre associated with Napoleon, which royalist propaganda would continue to propagate.

On the other side, Tsar Alexander was jubilant. His armies continued advancing westward, and he began to imagine himself as the mystical liberator of an enslaved Europe. In February, he entered Warsaw, declaring Poland “liberated”—though it had merely shifted from French to Russian domination, which did not sit well with the Poles. French troops, having been overwhelmed, had to retreat to the Oder, then the Elbe. However, the Russians could not continue their relentless advance.

The Tsar’s army had also suffered heavy losses, both in battle and due to the harsh winter. Strategically, Alexander had to leave troops in garrisons along his route to secure his supply lines. With his forces now far from Russia, he found himself with only 80,000 men at the front. Without a doubt, Alexander risked finding himself in Poland in the same predicament Napoleon had faced in Russia. To change the situation, he urgently needed to shift alliances, particularly with Austria, but first and foremost with Prussia.

Sweden, led by the French Marshal Bernadotte, who had been elected Crown Prince of Sweden, had allied with Russia. In return, Bernadotte hoped to annex Norway to his kingdom. He also harbored ambitions that he might be called upon to restore the monarchy in France.

Prussia, though hostile to Napoleon, hesitated to join the war alongside the Russians. However, General Yorck defected, aligning with Russia through the Tauroggen Convention and taking Königsberg, creating the first de facto starting point for a national war of liberation. He was joined by intellectuals like Baron von Stein, who called for German unity, a national revival, and a general mobilization to drive out the French occupiers.

His call resonated strongly among students and academics. On February 27, the King of Prussia, Frederick William, signed the Treaty of Kalisch in Breslau, sealing his alliance with Russia, and on March 17, he declared war on France.

The Prussian army was hastily rebuilt through the conscription of thousands of Jägers (“Hunters”), light infantry from the rural middle class (who had to pay for their own equipment), but above all through a general mobilization of men aged 17 to 40 to form a militia, the Landwehr.

Though some of these soldiers were also inexperienced, the enthusiasm surrounding the war of liberation made them a formidable force.

The imposition of conscription, the effects of the Continental Blockade, and the demands for soldiers had so aggravated the Germans that some northern regions rose up on their own. The Prussian monarchy could have taken advantage of this anti-French nationalist fervor, but its primary goal was to drive out the occupier and restore a monarchical and aristocratic system (in both Prussia and France). Thus, it was wary of these armed nationalist movements.

This desire to mobilize the entire populace, alongside the fear of losing control over it, was evident in the creation of the Landsturm (“Irregulars”), composed of all men aged 15 to 60 who had not been conscripted into the army and were tasked with harassing the enemy. Though the Landsturm existed on paper, they received neither uniforms nor weapons. In any case, with the Coalition advancing and Germany aflame, Eugène de Beauharnais was forced to abandon Berlin, while the French army retreated from Hamburg and Dresden. Arndt, Körner, and Rückert sang of the “holy war”…

Meanwhile, Austria watched the events of early 1813 with interest but hesitated. Tied to France by marriage, Austria, which Napoleon had defeated and spared twice, knew it stood to lose greatly if it joined the Coalition and lost. Moreover, its interests did not necessarily align with Russia’s. However, Austria also realized that if the Russians and Prussians won, it would have to answer for its loyalty to France. Caught between two fires, Austria took a “neutral” stance, acting as an arbiter while rearming itself, preparing to join the winning side when the time was right.

The United Kingdom, for its part, supported the Coalition and allied itself with Bernadotte’s Sweden, already allied with Russia. The country was still engaged in a conflict with the United States, but this was a distant war in which the Navy had the upper hand, a conflict that did not overly concern the Crown. In Spain, Wellesley’s troops (the future Duke of Wellington) had gained the upper hand, making an invasion of France via the Pyrenees a real possibility.

The Empire Strikes Back

On April 25, after entrusting the regency to Empress Marie-Louise, Napoleon takes command of the army at Erfurt. As he wrote, he intends to “put on the boots of Italy”! He has assembled four army corps and the Guard, totaling about 80,000 men. Young conscripts from 1813 have been joined by some veterans from the armies of Spain and Italy. The French army seems to have quickly healed its wounds, and Napoleon is ready to face his enemies. However, while infantry, artillery, and cavalrymen have been found in France (the imperial army is regaining a very national character that it didn’t particularly have in 1812), there is a critical shortage of horses and thus cavalry.

Napoleon joins forces with the troops of his former stepson, Eugène de Beauharnais, giving him 120,000 men, plus garrison troops. He has managed in a short time to reverse the trend and impose numerical superiority over the coalition, which at that moment has only 100,000 men. The Emperor knows he should rush towards Prussia, take Berlin to force the Prussians out of the coalition, and simultaneously intimidate the Austrian neighbor who might join the Russians at any moment. However, precisely to encourage Austria to join them, the coalition is campaigning near the Austrian border, in Saxony.

Napoleon cannot abandon his Saxon ally, risking seeing his other German allies turn away from him. And, since the enemy is there, he hopes to annihilate them in a decisive battle that he will constantly seek through multiple maneuvers.

On May 2, Napoleon marches on Leipzig and defeats the coalition at Lützen! The Prussians and Russians resist valiantly, losses are very heavy on both sides (the French lose 18,000 men, the coalition 20,000), and due to lack of cavalry to pursue the enemy, Napoleon cannot complete his victory. Paradoxically, as they had already done at Borodino, the Russians, although retreating and abandoning Leipzig to the French, consider the battle a victory…

The Grande Armée continues its counterattack, on May 8 it retakes Dresden, on the 10th it recrosses the Elbe, on the 21st it defeats the coalition again at Bautzen and Wurschen (another 40,000 dead in total, equally distributed between the two camps). Further north, Davout retakes Hamburg and Lübeck! In the southeast, French troops under Lauriston’s command advance to Breslau!

Sudden and brutal, the imperial counterattack is a frank success. Napoleon has recovered the territories he controlled in 1812, except for Poland. But, due to lack of cavalry (Napoleon has only 5,000 mounted cavalrymen), Napoleon is unable to achieve the decisive victory he hoped for. Moreover, the losses have been extremely heavy, a third of the Grande Armée is out of combat (dead and wounded), and, due to lack of cavalry, Napoleon has always been unable to exploit his victories as he would have liked.

On the evening of the Battle of Bautzen, he exasperates: “A butchery, and not a cannon taken, not a flag!” He knows he would need a respite to reform his army once again, so he accepts an armistice on June 4 at Pleiswitz, which is supposed to lead to a congress for peace.

From the Armistice of Pleiswitz to the Congress of Prague

While officially the Armistice of Pleiswitz aims to facilitate peace negotiations, in reality, no one is fooled; it is mainly a truce allowing each side to regroup its forces. For Austria, it is also an opportunity to officially contact the coalition as part of the talks. Taking advantage of the lull, Russia, Prussia, and the United Kingdom sign a pact on June 14. Victorious in Spain, England senses the moment for the spoils has come and offers two million pounds sterling to finance the war effort of the continental coalition, thus encouraging Austria to join their ranks.

Although officially neutral, Austria seriously considers entering the war on their side if the Prague peace negotiations do not succeed. It must be said that for the coalition, the news is good; on June 21, Wellesley crushed the French in the Iberian Peninsula at the Battle of Vitoria.

During the meeting between Metternich and Napoleon in Dresden on June 26, the Emperor clearly states that he does not intend to cede everything to the coalition. The ambassador reports these words:

“What do they want from me? That I dishonor myself? Never! I will know how to die, but I will not cede an inch of territory. Your sovereigns, born on the throne, can be beaten twenty times and always return to their capitals; I cannot, because I am a soldier who has risen through the ranks. My domination will not survive me; from the day I cease to be strong and therefore feared.”

From then on, all that remains is to make unacceptable proposals to France so that it refuses and the moral responsibility for the war can be placed on him. This is done when the abandonment of Holland and Germany, which France has just reconquered, is demanded. On the French side, no concessions other than Poland and the Illyrian provinces, already lost, can be accepted. Napoleon tries to negotiate, but the coalition has no intention of negotiating piecemeal what they can now take by force: on August 11, the Congress of Prague ends.

Despite letters from his daughter, Empress Marie-Louise, and under pressure from Metternich, Emperor Francis, who had already committed to the coalition on June 27, declares war on France, and thus on his son-in-law, on August 12. From then on, victory seems assured for the coalition; the arrival of reinforcements and Austria’s rallying give them a large numerical superiority over the French Empire. Indeed, Napoleon has managed to raise an army of 200,000 men for the campaign, mainly positioned in Saxony, but facing him, the coalition opposes three large armies:

- Bernadotte’s army in the North with 100,000 men, including Swedes, Russians, Prussians…

- Blücher’s army in the center, in Silesia, also composed of about 100,000 men.

- The Army of Bohemia in the South, commanded by Schwarzenberg, which alone counts 200,000 men.

The coalition also counts on the rallying of the German states.

The Allied Offensive

Napoleon disperses his forces, which may be a mistake. He sends Davout to march on Berlin, Ney against Blücher, and personally launches against the bulk of the allied forces: the Army of Bohemia, which he defeats. On August 27, Napoleon wins an important victory at Dresden, which the allies were trying to retake from Gouvion-Saint-Cyr, but for once, Schwarzenberg’s army manages to withdraw in good order. Although vastly outnumbered, the French lose “only” 8,000 men, while 27,000 allies are out of action and they abandon about forty cannons. During this battle, General Moreau, a Frenchman who had rallied to Russia, is mortally wounded by a cannonball that shatters his right knee.

However, Napoleon’s successes do not erase the setbacks of his marshals: Vandamme is defeated at Kulm, Macdonald is beaten on the Katzbach, Oudinot at Grossbeeren near Berlin, and Ney at Dennewitz. The allies only attack from a position of strength; they fear Napoleon and avoid confronting him personally. Each battle thins the ranks of the Grande Armée while the allied ranks seem to always replenish thanks to the mobilization of the Prussians.

Among the young French conscripts, the setbacks directly impact morale; many decide to desert, or even mutilate themselves to be discharged. Extreme fatigue linked to forced marches, diseases (fevers, typhus…), bivouacs in the open air in increasingly harsh weather, and lack of supplies also contribute to defections.

Napoleon orders deserters to be decimated, meaning that for every ten deserters caught, one is shot. But this does not address the root of the problem; the Grande Armée is forced into rapid and exhausting marches to surprise the enemy, and logistics can’t keep up: while the French lack light cavalry, this is not the case for the allies, who are thus able to constantly threaten and harass supply lines. Russian Cossacks excel in this area, charging at full speed on convoys, attacking isolated groups and lost soldiers… Supply wagons that have time form circles to repel the assaults of those whom Sergeant Faucheur nicknamed “the Mohicans of the North”.

By the end of September, Napoleon finds himself forced to adopt a defensive position, with the bulk of his army in the city of Dresden (130,000 men), and the rest around Leipzig (72,000 men). Davout also has 30,000 men, but far away in Hamburg. In early October, the allies launch a massive offensive on the Elbe.

To try to prevent the reunion of the allied armies, the Emperor directs his forces towards the city of Leipzig.

Leipzig: The “Battle of Nations”

Napoleon failed to unite all his forces in Leipzig when the fighting began on October 16, finding himself at a significant numerical disadvantage: 250,000 coalition troops against 185,000 French. The battle started around 9 am on October 16, 1813, under a low, gray sky and in the rain. Napoleon positioned himself around the city, with Marmont facing Blücher’s troops in the North, while in the South, Poniatowski, Victor, and Lauriston, supported by Augereau and Macdonald, faced Schwarzenberg’s imposing army. The fighting on the 16th for control of the southern villages was extremely violent, with the village of Wachau, defended by Victor’s men, changing hands several times throughout the day.

However, around 11:30 am, the Grande Armée seemed to have repelled all the coalition attacks, and Napoleon decided to take advantage by launching a counterattack with 12,000 cavalry and two divisions of the Young Guard! But the enemy, in turn, absorbed the blow without breaking its line, the Austrian reserve entered the fray, and the Grande Armée was cut short in its momentum. At the end of this deadly day, neither side had gained the upper hand, with Napoleon losing 20,000 men killed or wounded, and the coalition 30,000. Faucheur, promoted to sergeant-major, offers us a grim snapshot of one of the many tragic scenes of the day:

We were on the march […] when we were very vigorously attacked from the front and flank by an enemy two to three times more numerous than us. We quickly formed into squares by battalion to withstand the charges of cavalry that threatened to assault us vigorously. My captain, behind whom I was standing, had just instructed our men to fire on the cavalry only at his command, when a shell took off the back of his head and covered me in blood. The shell, continuing its path, passing a few centimeters from my face, fell into the square and took off a foot of the drum major. We waited for the charge without flinching and only firing at about twenty-five or thirty paces, we stopped the cavalry’s momentum. During the evening, we endured three or four cavalry charges that were no more successful. Our artillery didn’t let them get as close as the first time and sent them a barrage of grapeshot. The enemy artillery returned the favor; we received our fair share, but nevertheless not as much as a square of a marine regiment that was near us and one of whose faces was somewhat demolished.

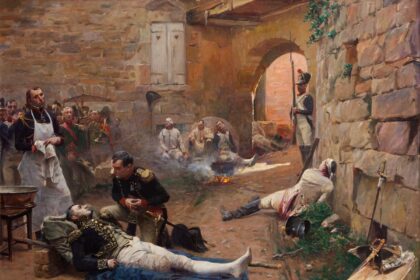

In the city of Leipzig, the wounded were pouring in, churches were transformed into makeshift hospitals where amputations were performed constantly. Prisoners were herded into cemeteries, and to shelter them, vaults were even opened, and some cooked their meals among the skeletons. For Napoleon, the situation was becoming complicated, and he knew it: while tactically there was a stalemate, with each side having repelled the other’s assaults, strategically the coalition had the advantage. They would indeed have time to receive reinforcements from Bernadotte and Bennigsen, while Napoleon would only receive Reynier’s corps, partly composed of unreliable German troops.

The troops slept on the battlefield, and the next day, October 17, Napoleon requested an armistice from the coalition with a view to peace. They refused. Napoleon, although decided to withdraw, remained in his positions waiting for Reynier’s arrival. He assumed that the coalition would not be able to attack again before the 19th. On the night of October 17-18, the Grande Armée and its 150,000 men retreated to Leipzig, Napoleon, with his back to the city, tightened the ranks. The French army formed an arc around the city: Ney and Marmont in the North faced the armies of Blücher and Bernadotte, in the East Sébastiani positioned himself against Bennigsen, in the South Poniatowski, Victor, and Lauriston continued to face Schwarzenberg’s army, in the West Bertrand was tasked with guarding the only retreat route.

At dawn, the coalition, with 250,000 to 300,000 men, advanced in a general offensive along the entire French line: the objective was thus to engage the entire Grande Armée in the melee and prevent Napoleon from attempting skillful maneuvers. The same scenes of fierce fighting that had taken place on the 16th were repeated on the 18th around the villages south of Leipzig, still in the South…

But always a little closer to the city… In the North, Ney repelled the enemy’s assaults as best he could. But suddenly, what is considered one of the greatest tragedies of the battle for Napoleon occurred: the Saxons and Württembergers serving in the Grande Armée betrayed and turned their weapons and cannons against their former comrades (only the Saxon Royal Guard, which was alongside Napoleon, remained loyal; the Emperor later sent them back so they could rejoin their sovereign who had remained faithful to Napoleon and would be treated as a prisoner of war by the coalition).

The betrayal opened a real breach in the French lines, the coalition tried to exploit it, General Bülow took the initiative and was only stopped at the last moment by Nansouty’s cavalry, which managed to outflank him. The village of Schönefeld changed hands no less than seven times! In the South, the cannonade was terrible, a witness recounts that in the city itself it would have been impossible to hold a glass full of water, so much did the ground shake. The battle only ceased with nightfall, the soldiers spent the night on the battlefield itself.

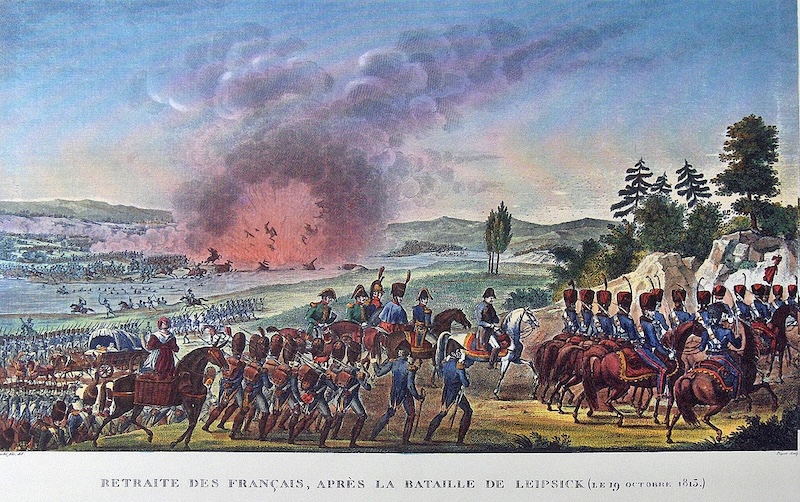

The French had lost 50,000 men during the day, the coalition 60,000. Napoleon, having returned to Leipzig, organized the retreat which seemed the last option to save the Grande Armée while there was still a road to the West.

On the night of October 18-19, 1813, the Old Guard crossed the bridges over the Elster to establish themselves west of Lindenau. They were followed by Kellermann’s cavalry, Augereau’s and Victor’s corps, Sébastiani’s cavalry… But an improvised bridge for the retreat collapsed, leaving only one bridge for the entire Grande Armée to cross the Elster! Inevitably, bottlenecks occurred.

Meanwhile, Dombrowski and Reynier protected the North, Marmont the East, and the trio of Macdonald, Lauriston, and Poniatowski the South. Seeing that the Grande Armée might escape them, the coalition rushed towards Leipzig and reached the suburbs, bloody fighting took place at the gates of Leipzig while the Grande Armée slowly retreated across the single bridge. Sergeant-Major Faucheur, defending in the East in Marmont’s sector, reports:

In the morning, we were furiously attacked by Blücher on our front, and on our left by the Swedes […]. Sheltered by the houses, we firmly awaited the enemy’s attacks. Each time they tried to force their way into the village, we covered them with our fire, then we charged at them with bayonets, but when we had the misfortune to leave the village and show ourselves in open country, in pursuit of our assailants, we were immediately riddled with grapeshot and forced to return to the village. Then the enemy would reform its columns and, throwing themselves at us headlong, would push us back sometimes to the middle, sometimes to the last houses of the village. In turn, we would charge back with cries of ‘Long live the Emperor!’ and we would retake the lost ground […]. We lost Scönfeld seven times and […] seven times we retook it.

To prevent the coalition from pursuing him, Napoleon had ordered the bridge to be blown up as soon as his army had crossed. Colonel Montfort, commanding the engineers, entrusted this mission to a corporal, but the latter, deceived by the sight of a few enemy soldiers, blew up the bridge while Poniatowski’s, Macdonald’s, Lauriston’s, and Reynier’s troops had not yet crossed! This is the second great tragedy of the battle for Napoleon, and he has often been reproached, as well as his chief of staff Berthier who did not dare to take initiative, for not having previously built several bridges to ensure the retreat.

Some of the soldiers trapped on the wrong side of the river tried to swim across, including Macdonald and Poniatowski. But the latter, already suffering from several wounds, including one in the back, drowned. Lauriston and Reynier were taken prisoner with a good part of their men (12,000 men). A significant portion of the French artillery park, 150 cannons, as well as the baggage train (500 wagons) fell into enemy hands. The four days of combat had resulted in more than 160,000 dead in total, it would take months for the citizens of Leipzig to bury all the bodies… Numerically, it was the largest battle of the Napoleonic wars, Europe would not see such an engagement again until 1914.

The Retreat and the End of the German Campaign

The French are forced to retreat, the battered regiments withdraw amidst a cloud of isolated men, the exhausted and starving troops resupply themselves from the local population, with the abuses that this entails. Faucheur reports:

On October 19 and 20, all armed men had indeed been brought into the ranks; but there was also a very large number who, lame, sick or wounded, marched without weapons between our columns, presenting a frightening spectacle of demoralization. These men, for the most part not belonging to the regiments with which they marched and unable to be restrained by the bonds of discipline, threw themselves like vultures on the villages in sight and removed all the resources that would have been so precious for the rest of the army. They rarely benefited from their findings for long; almost always they were killed or captured by the Cossacks who never attacked our columns but always prowled in the vicinity.

Nevertheless, despite the disproportion in the balance of power, the French managed to hold their ground against the coalition forces and save the army from destruction. Much weakened, the coalition forces pursue them only very half-heartedly, allowing them to fall back to the Rhine. On the evening of the 19th, the King of Prussia appoints Blücher as Field Marshal of all armies, and Francis I elevates Metternich to the title of Prince. The victory of the coalition forces, sometimes called the “Battle of Nations” (10 different nations participated in it), truly appears as the apotheosis of a German nationalism that had fermented during the French occupation.

One man, however, will genuinely attempt to stop Napoleon in his retreat: the Bavarian General de Wrède, a former ally… He wants to cut off the French route to Mainz with his 50,000 soldiers and sixty cannons. Although weakened, Napoleon still has about a hundred thousand men; he sweeps away de Wrède’s troops at Hanau and can thus cross the Rhine again.

During this last battle, the French lost 2,000 to 3,000 killed or wounded, while the Austro-Bavarians counted 1,700 killed, 3,100 wounded, 4,300 prisoners, and lost several pieces of artillery. Ironizing on the Bavarian’s defeat, Napoleon quips, “Poor de Wrède, I was able to make him a count, but I couldn’t make him a general”…

On November 2, 1813, Napoleon is in Mainz; on the 9th, he is at Saint-Cloud. To try once again to halt the progression of the coalition forces, he orders a new levy of 300,000 soldiers, increasingly young and inexperienced. The first months of 1814 bring sad news: in Alsace, the first elements of the Army of Bohemia have crossed the Rhine, the English have crossed the Pyrenees, in Naples Murat attempts to save his crown and abandons the Emperor to sign a peace treaty with Austria.

Napoleon now intends to cast the shadow of 1793 before the coalition forces. Revealing unparalleled military genius, Napoleon engages in the French campaign, a swan song with the appearance of a fateful apotheosis.