One of the most well-known conflicts from antiquity was the Battle of Marathon. Conflict escalated between the Greeks and Persians during the First Persian War (Greco-Persian Wars). The Persian king Darius I sent an army to Greece in 490 BC with the goal of conquering Athens. The Persians, fresh off their conquest of the Aegean islands, landed not far from the city. The Athenians, with help from the Plataeans, managed to thwart the invaders without calling in the Spartan reserves. Athens’ hegemonic position in Greece was bolstered by this victory.

What were the causes of the Battle of Marathon?

The Achaemenid Empire (Persian Empire), founded by King Darius I and thriving by the end of the sixth century BCE, was also known as the Persian Empire. The Persian Empire dominated the entire Middle Eastern region and even pushed further westward.

A number of Greek cities in Ionia, which was located on the west coast of modern-day Turkey, as well as the kingdoms of Thrace and Macedon, fell under Persian rule. The Greeks viewed the Persians as haughty savages who were obsessed with wealth and luxury and worshiped their king as if he were divine. The political and cultural distance between the two was too great for the Greeks to accept Persian rule.

First Persian War broke out when Ionia rebelled against its occupiers in 499 BC. In 494 BC, the Persians captured Miletus and ultimately defeated the rebels, who had military support from Athens and Eretria. Greek islands like Lesbos and Tenedos were also taken. Darius I of Persia had issued an ultimatum to Athens and Sparta.

He dispatched envoys to them, some of whom met violent ends. Darius sent a punishing expedition to mainland Greece in 490 BC because he was fed up with the Greeks’ stubbornness and wanted to punish Athens for aiding the Ionian rebels. As they advanced westward across the Aegean Sea, the Persians sacked the city of Eretria and deported many of its citizens to the region of Lower Mesopotamia.

When and where did the Battle of Marathon take place?

Hippias, a former Athenian tyrant, aids Darius in his campaign. Exiled twenty years prior, Hippias yearned for vengeance and the chance to reclaim power in Athens. He suggests that Darius set down near Marathon, about 38 kilometers from Athens. The plan was to distract the Athenians long enough so that their city would be defenseless.

The Persians arrived in Marathon around September 12th, 490 BC. The Athenians marched out to meet the enemy under the direction of their strategist Miltiades, but they refrained from attacking right away. From a distance of 1,500 meters, both armies stared at each other across the battlefield.

There are between 9,000 and 10,000 hoplites in the Greek army, plus another 1,000 Plataean soldiers and an untold number of freed slaves. To the contrary, the Persian expeditionary force was vastly outnumbered. Greek historians estimate that the Persian army strength was between 200,000 and 600,000. Historians of the modern era place their total male population somewhere between 20,000 and 100,000. Artaphernes, Darius’s nephew, led the Persian army, while Datis helmed the navy.

Who won the Battle of Marathon?

The Persian cavalry disembarked on September 17th, 490 B.C., and a portion of the fleet sailed toward Athens’ port of Phalerus. The remaining troops made their way on foot into the city. Therefore, the Greeks must first stop the invaders from getting closer to the city before returning there to defend it from the Persian fleet. They anticipate reinforcements from Sparta, where Pheidippides had gone to sound the alarm.

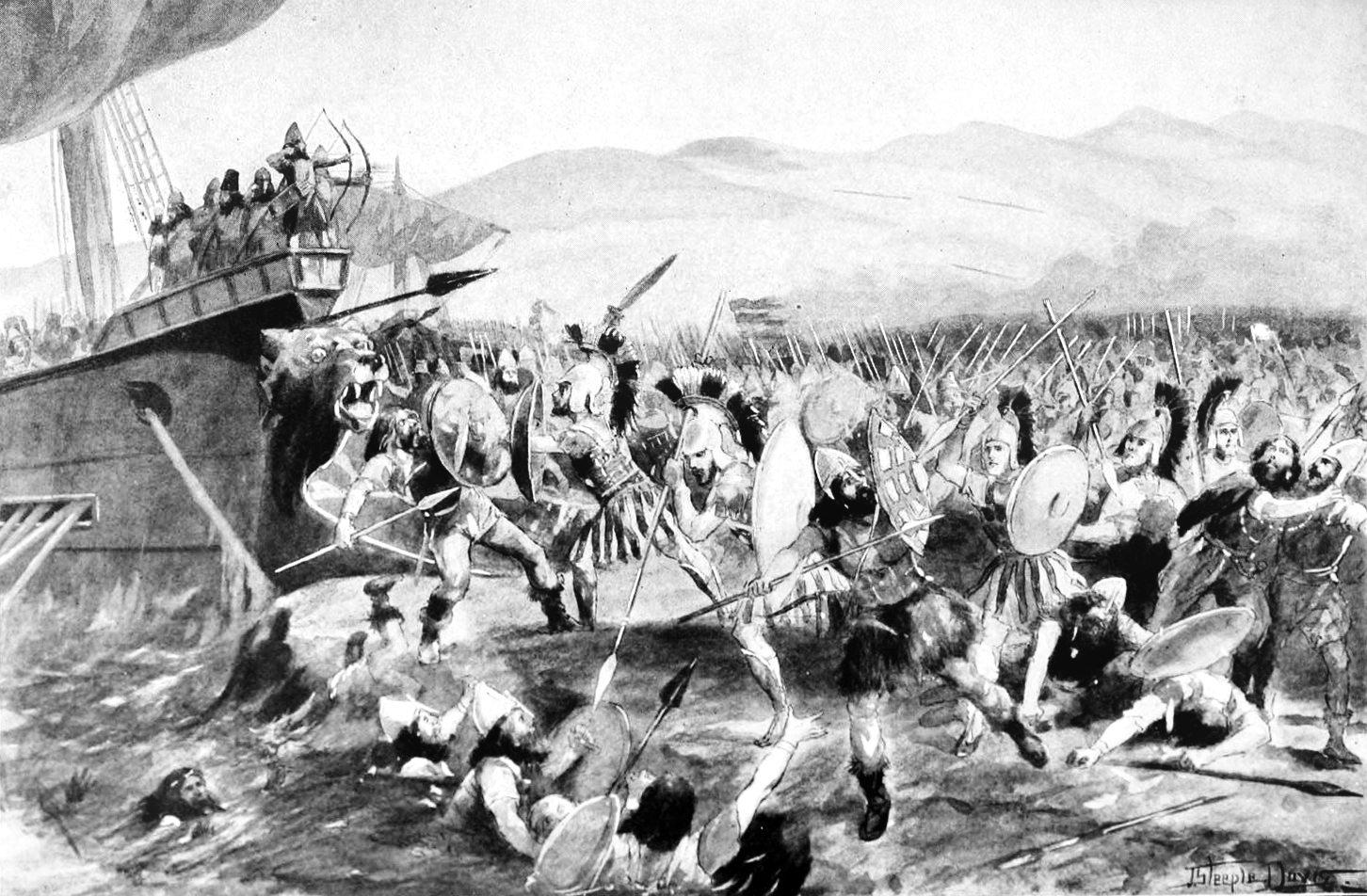

The Greek army, despite being outnumbered, launches the initial assault. It’s likely that the defenders took advantage of the retreating Persian cavalry. The gear of Greek hoplites was top-notch. They have a sword, a long spear, and a very strong shield, and they wear a cuirass, a helmet, and leggings for protection. The Greeks deploy the phalanx formation, where they form a wall with their shields and charge their enemies from behind.

The enemy was defenseless against this level of heavy infantry. When pitted against Greek weapons, Persians have no chance in a fistfight. The Athenians charge forward without ducking for cover from incoming arrows. Persians are taken by surprise and are unable to hold off the Greek charge, so they run for the water in an attempt to reach their ships. The elite Persian forces in the center of the line fought valiantly for some time before being caught in a pincer movement and rendered useless.

The Greeks only lost around 200 men, while the Persians lost 6,400. Seven ships from the Persian fleet were taken. The Athenians returned to defend their city from the remaining Persian fleet after this victory. They marched for eight hours straight and eventually made it to their destination. Seeing that their plan had failed, the Persians abandoned any hope of landing. Just a few days later, reinforcements from Sparta arrive, but it’s too late to save Athens.

Who was the first marathon runner?

As soon as the Athenians learned of the Persian landing, they dispatched a messenger to Sparta to ask for help. A remarkable feat was accomplished by the messenger Pheidippides, who travels the 250 kilometers from Athens to Sparta in just 36 hours. However, the Spartans at the time were in the midst of the Karneia, celebrations in honor of Apollo, and so they were unable to send troops for ten days. An alternate account had the Greek general Miltiades sending a man named Eucles to Athens to announce the Greek victory at Marathon. Fatigue took its toll on the messenger shortly after he delivered the news.

An academic named Michel Bréal was moved by these feats to include a marathon competition in the Olympic Games when they were held in Athens in 1896. This roughly 40-kilometer footrace begins at the historic Marathon site and concludes at Athens’s Panathenaic Stadium. In 1896, Spyrdon Lois of Greece won a 38-kilometer race in Athens by a margin of over two hours and fifty seconds. Ever since then, there have been dozens of marathons in cities all over the globe. Additionally, since 1983, the Spartathlon had been held in memory of Pheidippides as a 246-kilometer long-distance race between Marathon and Sparta.

The results of the Battle of Marathon

After defeating the Persian army without assistance from the Spartans, Athens gained a lot of respect. In 478 BC, to combat the persistent Persian threat, it established the Delian League. The victory at Marathon was cited often by the arrogant city to prove why it was superior to all the other cities.

The significance of this victory for Athens cannot be overstated when discussing its political significance. The city had been saved thanks to the sacrifice of the hoplites, citizen-soldiers who are willing to give their lives for their city. But Athenian imperialism would eventually run into resistance from Sparta 40 years later, sparking the Peloponnesian War. Because of this triumph, the First Persian War was also over.

The Persians do not see the Battle of Marathon as a major loss. While Athens might have been unbeatable, the Persians were successful in seizing control of the islands in the Aegean Sea. After putting down a revolt in Egypt, Darius I planned another expedition. The king passed away in 486 BC, never getting to lead his army into battle against Greece. During the Second Persian War (486 BC), his son Xerxes I was in charge of it. The war culminates in the peace of Callias, but not before the heroic sacrifice of Leonidas and the Spartans at Battle of Thermopylae and the devastating naval battle at Salamis.

Bibliograpy:

- Krentz, Peter. The Battle of Marathon. Yale University Press, 2010

- Lanning, Michael L. (April 2005). “28”. The Battle 100: The Stories Behind History’s Most Influential Battles. Sourcebooks. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-1402202636.

- Davis, Paul K. (June 2001). “Marathon”. 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195143669.

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-44-435163-7.

- Finley, Moses (1972). “Introduction”. Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Rex Warner. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044039-9.

- D.W. Olson et al., “The Moon and the Marathon”, Sky & Telescope Sep. 2004