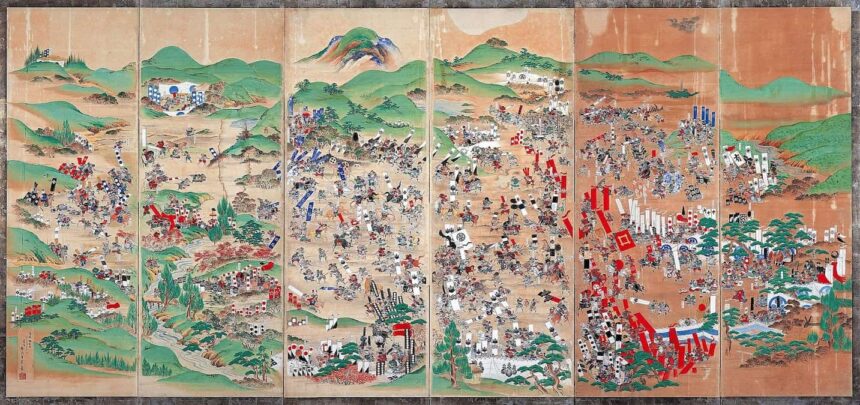

For four centuries, every Japanese person has known this battle, having learned about it from childhood. The Battle of Sekigahara was the largest gathering of samurai in history. On those October days in 1600, this mountainous pass in central Japan, located between Kansai (Western Japan) and Kanto (Eastern Japan) at the intersection of major routes, became the stage for a massive confrontation.

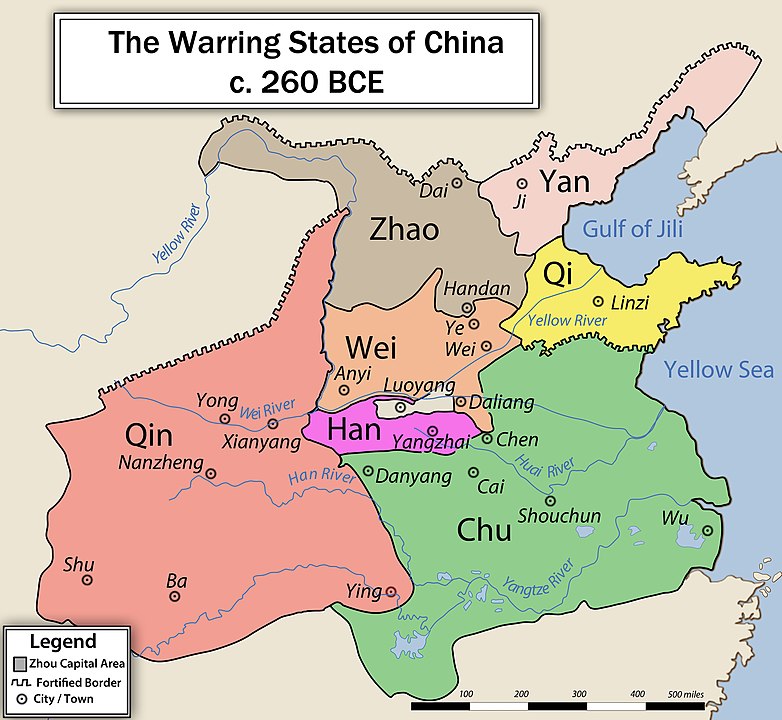

The outcome of this battle marked Japan’s transition from the chaotic Sengoku period (“Warring States period”) to a long era of peace—one that brought stability and centralization but also isolated the country from the outside world. This event was so pivotal that the Japanese call it tenka wakeme no kassen, meaning “the battle that decided the fate of the nation.”

A Century of Chaos in Japan

At the time, this bloody conflict concluded nearly 150 years of relentless warfare. In the 16th century, the rise of a new merchant and bourgeois class, combined with the weakening of the shogunate, had reshuffled the balance of power. The economy was in shambles: poverty in the countryside forced peasants—who made up half the population—to serve as soldiers for local warlords (daimyos) who fiercely competed for control of their territories. Japan’s insular nature, coupled with this internal turmoil, provided opportunities for ambitious new leaders. The introduction of firearms in the mid-16th century, brought by Western traders, further accelerated the rise of skilled and ruthless warriors who rapidly climbed the ranks.

Who were the key leaders in the battle?

The Fall of the Muromachi Shogunate

In 1573, one such warlord, Oda Nobunaga, ousted the reigning shogun, bringing an end to the Muromachi period (named after the Kyoto district where the shoguns had ruled for 250 years). The empire was now tenka fubu—”under the rule of the sword”—a phrase that proved all too true. However, in 1582, betrayed by his own men, Nobunaga took his own life. His rule was succeeded by one of his most capable generals, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a man from a humble background who continued Nobunaga’s campaign of conquest and unification with great success.

Between 1592 and 1597, however, Hideyoshi made a grave mistake. Seeking to channel the military energy he had harnessed, he launched an invasion of Korea—intended as the first step toward conquering China.

But the Koreans resisted with unexpected ferocity. The Japanese forces were ultimately driven back into the sea. The failure devastated Hideyoshi, and he died in 1598. His death left a massive power vacuum. His seven-year-old son was too young to rule, and although a council of five regents attempted to hold the fragile state together, it soon crumbled.

Mitsunari and Tokugawa: Two Contenders for the Throne

The collapse of power sparks the ambitions of two rivals. The first is Ishida Mitsunari, the leader of the “bureaucrats” who had administered the regime. A former representative of Toyotomi in occupied Korea and one of his most brilliant vassals, he presents himself as Toyotomi’s most loyal disciple. The second is Tokugawa Ieyasu, who holds the title of “first regent.” Twenty years older than Mitsunari, this formidable warrior and cunning politician, now 57, had long represented Toyotomi in the Kanto plains to the east, where he had carved out vast domains with Edo (modern-day Tokyo) as his base of operations. In a Japan searching for a sovereign, there is no room for two, and as the 17th century dawns, both warlords begin mustering their forces.

Ishida is the one to launch hostilities. Convinced that the balance of power is in his favor, he calls upon the daimyos to rise up, gathers his supporters in Sawayama, and allies with Mori Terumoto, the commander-in-chief who controls Osaka. In response, Tokugawa Ieyasu mobilizes an army, splitting it in two and sending his forces west along separate routes. But Ieyasu knows that war is not just about battlefield strategy—it is also about intrigue and betrayal. Distrusting both his allies and his enemies, he remains in Edo, letting his troops know that he will only join them once he is sure of their loyalty in battle.

His caution proves justified: he soon learns that his forces have crushed a daimyo from the Toyotomi clan allied with Ishida. Reassured, Tokugawa sets out from Edo toward Osaka Castle in the west, where the bulk of the enemy troops are stationed. Faced with the growing threat, Ishida has no choice but to march out to confront him and block his advance. Tokugawa has won his first strategic victory—he has drawn his enemy’s forces into open terrain, avoiding a long and grueling siege. On October 20, 1600, after a long day of marching through torrential rain that has exhausted his men and rendered firearms useless, Ishida orders a halt and rest in the mountainous pass of Sekigahara.

The topography of the area—a valley bathed by the small Fuji River—offers Ishida’s army, positioned on the heights, a strategic advantage. Upon hearing of this movement, Tokugawa advances his troops into battle. For months, aided by a network of spies, he has been negotiating with some of Ishida’s allies, persuading them to defect—most notably with one of the most powerful among them, the young Kobayakawa Hideaki.

A former commander in Korea and the nephew of the late Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Kobayakawa had once fallen out of favor due to command errors, but Tokugawa had helped reinstate him. Now, the young warlord is torn between loyalty to the Toyotomi clan, which supports Ishida, and his gratitude toward Tokugawa. Eventually, he sends a secret message to Tokugawa, assuring him that he will switch sides during the battle. Tokugawa, taking his first major gamble, chooses to trust him.

Cannons, Rain, and Fog Over Sekigahara

The rain and fog are so thick that the two armies collide before even seeing each other. Panic. Gunfire. On the evening of October 20, both sides withdraw without engaging in full combat. Ishida rejects the idea of exploiting the situation as dishonorable, ignoring the advice of one of his generals, Shimazu Yoshihiro, who feels humiliated and will remember this slight the following day—leading him to betray Ishida.

At dawn on October 21, as the fog begins to lift, both armies take stock of their positions.

Perched on the heights, Ishida’s so-called “Western Army,” 80,000 strong, looks down upon Tokugawa’s 75,000 men, seemingly trapped in the valley below.

In Japan, the first samurai to charge into battle earns great respect. This honor falls to Tokugawa’s fourth son, a 21-year-old warrior.

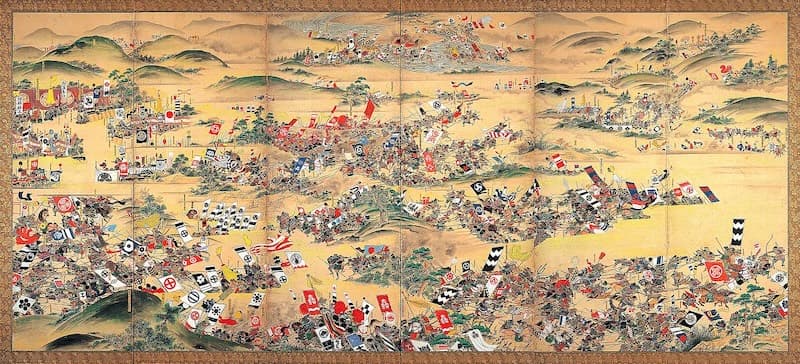

At precisely 8 a.m., 30 cavalrymen ride behind him through the left flank of their “Eastern Army,” followed by 800 arquebusiers who open fire on the center-right of Ishida’s forces. The ascent is steep, the ground waterlogged, and the advance too slow. The assault is repelled with heavy casualties. Yet, despite Tokugawa’s weaker position and numerical disadvantage, his superior firepower tips the balance: his muskets have fared better in the damp conditions, and before the battle, he had seized 18 cannons from a Dutch ship, Liefde. These cannons now rain destruction upon the battlefield, their shots exploding amid forests of spears, cavalry charges, and deadly sword fights.

The Fatal Betrayal

By midday, the battle reaches a standstill. Confusion reigns, and the outcome remains uncertain. All eyes turn southward to Mount Matsuo, where 15,000 warriors under Kobayakawa Hideaki stand motionless above the chaos, awaiting their leader’s decision. The young commander hesitates, ignoring Ishida’s repeated orders to attack as well as Tokugawa’s messages reminding him of his promised defection.

Then, in a fateful move, Ieyasu makes a decision that will become legendary—he orders his cannons to fire upon Mount Matsuo. The thunderous blasts jolt Kobayakawa into action. At last, he commits. With a sweeping motion, he commands his entire force to descend in support of Tokugawa, siding with the old warlord to whom, in the end, he feels indebted.

Ishida’s troops, stunned by this betrayal, turn their arquebuses against the defectors, limiting the effectiveness of their charge and even driving them back up the hill. But Tokugawa’s other regiments seize the moment, capitalizing on the disorder to break through the right flank of the Western Army.

Witnessing this dramatic shift, four of Ishida’s generals also turn against him, including Shimazu, still nursing his grudge from the previous day. When Ishida orders him to attack, he coldly refuses, declaring that he does not take commands from a leader he does not respect.

The verdict is clear. The Western Alliance is revealed to be nothing more than a fragile coalition. The bold gamble of the seasoned warrior has outmatched the refined administrator. Ishida’s army collapses—both in spirit and on the battlefield. In the aftermath, 40,000 of his men are executed.

A Dictatorship of Peace

From this moment on, Japan turns inward. Abandoned by his allies and handed over to Tokugawa Ieyasu, Ishida Mitsunari is paraded through the streets of Osaka before being taken to Kyoto, where he is beheaded on November 1, 1600, along with three other “troublemakers.” As per custom, their severed heads are displayed on Sanjo Bridge. Kobayakawa Hideaki, whose betrayal altered the course of history, is rewarded by Tokugawa with a vast domain. Yet, he enjoys it little—he dies just two years later, having succumbed to madness.

In 1603, Tokugawa is granted the coveted title of shogun by the emperor, an honor denied to his two predecessors due to their humble origins. This official recognition cements his success, allowing him to complete Japan’s unification. He confiscates and redistributes the lands of his former enemies to loyal men. More importantly, to prevent the regional fragmentation that had long plagued Japan, he reduces the number of feudal domains. Each han (fief) now becomes an administrative unit overseen by a representative of the central government, to whom he must answer.

Thus a nation was born that isolated itself from the outside world like a patient in convalescence. In Kyoto, the emperor remained the symbolic heart of the nation, while his enforcer, the shogun, ruled from Edo. The Tokugawa shogunate would last until 1868, and the Battle of Sekigahara would be seen as a defining moment in the birth of modern Japan.

Q/A on the Battle of Sekigahara

What caused the Battle of Sekigahara?

The battle was the culmination of a power struggle following the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1598. Tokugawa Ieyasu sought to consolidate power, while Ishida Mitsunari rallied loyalists to protect Hideyoshi’s heir, Toyotomi Hideyori.

What were the Eastern and Western Armies?

Eastern Army: Led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, it included daimyo (feudal lords) from eastern Japan. Western Army: Led by Ishida Mitsunari, it consisted of daimyo loyal to the Toyotomi clan, primarily from western Japan.

What was the significance of Sekigahara’s location?

Sekigahara, located in modern-day Gifu Prefecture, was a strategic crossroads. Its narrow valley forced the Western Army into a confined space, limiting their mobility.

What were the key mistakes of the Western Army?

Poor coordination: Lack of unity among the daimyo.

Betrayals: Key commanders defected to the Eastern Army.

Ineffective leadership: Ishida Mitsunari’s inability to inspire loyalty.