The Battle of Strasbourg (Argentoratum, 357) pitted the Roman army led by Emperor Julian the Apostate against a coalition of Alamanni barbarian tribes attempting to invade Gaul. During the 4th century CE, the Romans experienced a period of relative tranquility on their borders, primarily due to successful military campaigns that restored the Roman army to its former glory. The Battle of Strasbourg, where Emperor Julian distinguished himself, temporarily halted major barbarian incursions across the Rhine, earning its victor immense prestige.

—>The Roman forces in the Battle of Strasbourg were led by Emperor Julian the Apostate. Julian later became known for his military prowess during his short reign as Roman Emperor.

Background to the Battle of Strasbourg

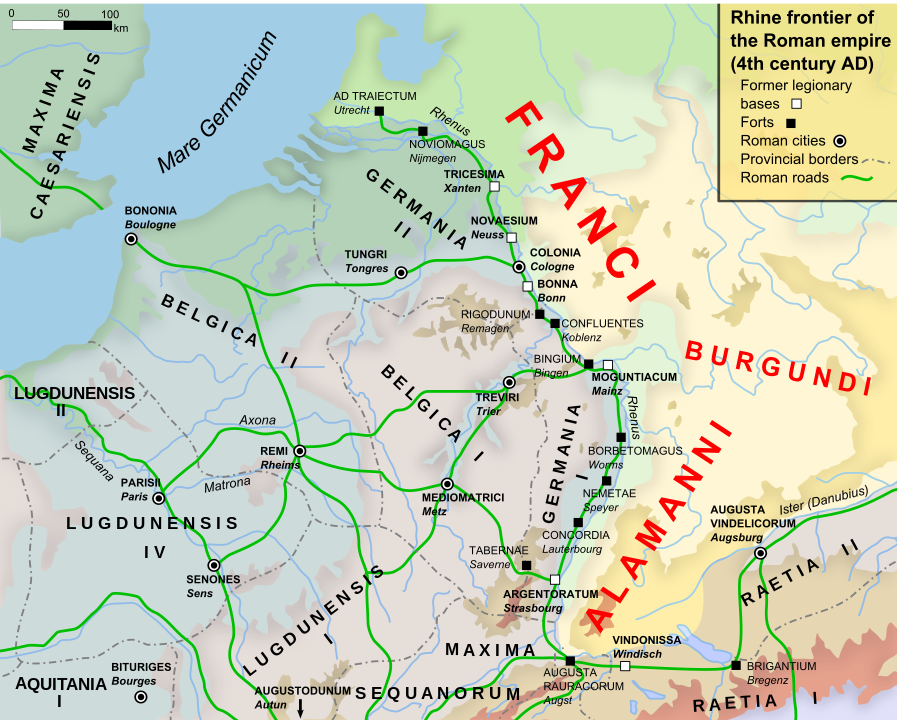

In 357, the young Julian, appointed as Caesar in Gaul by his cousin Constantius II for two years, fought against the Alamanni on the Rhine border to restore tranquility to the lands of the Empire. The Alamanni had occupied several cities and fortified elements in imperial territory because Constantius, in his struggle against the usurper Magnentius, had incited a barbarian attack on his rival’s rear to weaken him.

Despite achieving victory (the Battle of Mursa Major in 351), the emperor had not resolved the situation on the borders, where the Alamanni still held firm. He assigned his cousin the task of eradicating the barbarian threat along the Rhine in response to Sassanian Persian movements.

However, Constantius, wary of potential dissent, had surrounded the new emperor with a group of his own men to exert control. Despite this, Julian operated with audacity and foresight, managing to rectify the situation in a few years. However, the Alamannic threat persisted despite Julian’s efforts. The army under the command of General Barbatio suffered a severe setback, surprised and routed by the barbarians.

Julian the Apostate Faced with an Outbreak of Violence

Upon receiving this news, several Alamannic kings gathered their forces to reconquer the territory they had taken from the Empire. Among them were Chnodomar, Vestralp, Urius, Urcisin, Serapion, Suomar, and Hortar. A significant event had united the barbarians under a common banner: King Gundomadus, a loyal supporter of the Romans and true to his word, as stated by the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, had been killed in an ambush. This event further fueled the rebellion against Rome.

Informed of the relatively small size of Julian’s troops (around thirteen thousand men) by a defector from the Scutarii of the defeated army of Barbatio, the barbarians anticipated an easy operation, considering their probable number to be around thirty thousand. Nevertheless, Caesar resolved to engage in battle. Leading his army out of the camp, he marched towards the barbarian fortification.

Upon reaching the vicinity of the enemy, he gathered his troops and delivered a vigorous speech. Motivated by his words and proud of having an emperor among them, the soldiers began a tumultuous display of shouts and the clashing of weapons against shields.

This behavior mirrors that of Roman fighters of the time, who, in a manner similar to the barbarians, expressed their warrior spirit through a demonstration of brutal violence. The almost miraculous role of the victorious emperor as their protective leader significantly heightened their combativeness. In response, the senior officers of the army also favored engagement. Once the enemy was dispersed into numerous marauding units, operations became a nightmare, both tactically and logistically, and instilled terror among civilian populations.

Julian’s successful operations outside the Rhine on the very frontiers of the barbarians further increased Roman confidence. There, they encountered no opposition, as the enemies withdrew without a fight. From their perspective, they were about to face cowards who had refused to defend their own lands.

Setting Up An Army

The Roman army established itself on a gently sloping hill, very close to the Rhine. An Alamanni scout fell into the hands of the soldiers, revealing that the barbarians had crossed the river for three days and nights and were approaching their position.

Shortly after, the troops witnessed the barbarian warriors spreading across the plain and forming a wedge—an attack formation with a narrow front aimed at breaking through the enemy lines in a vigorous charge. The Roman response was swift, and the soldiers formed an “indestructible wall” (Ammianus Marcellinus, XVI, 12, 20). The shields of that Roman era were primarily circular, offering protection often likened to Greek shields.

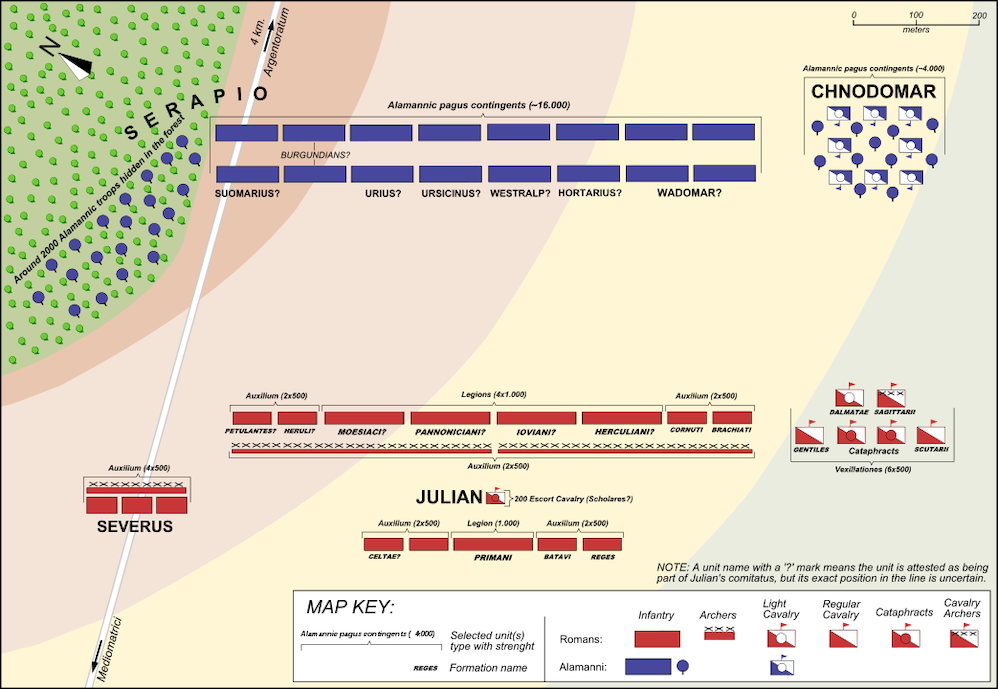

Facing the Roman cavalry on the right wing, the barbarians positioned their own cavalry on the left, mixed with light troops, employing an ancient Germanic tactic. They advanced with thousands of fighters to ambush the Romans on their right, behind a wood. The kings, leading their troops, were ready to set an example.

Ammianus described Chnodomarius, the soul of this coalition, as a fearsome warrior with strong muscles. Serapion commanded the right wing; his name, derived from his father, signified his status as a hostage in Gaul, initiating the mysteries of Eastern religions.

Severus ordered the left wing of the Roman army to halt its advance when it became aware of the barbarian ambush. Julian, with his two hundred elite cavalry, moved through the ranks, encouraging his men while trying, as mentioned by Ammianus, not to appear overly eager for honor, as Constantius had placed him under close scrutiny. He organized his men effectively and shouted powerful declarations, appealing to their pride as warriors.

He thus established his battle line in two rows, keeping the Primani legion and Palatine auxiliaries in reserve and the elite troops heavily equipped, similar to the units on the front line. The legions of that time were of a smaller size, probably around a thousand men, as they formed more mobile groups than the ancient legions of 5000 men.

For the ‘small war’ operations usually carried out by the barbarians, these units were much more effective. Similarly, palatine auxiliary units were composed of 500 men but typically operated in pairs, such as the Cornuti and the Bracchiates, positioned on the right of the first line.

These troops were largely recruited from the barbarian world, but their combative zeal and loyalty to the Roman Empire were noteworthy. They were highly reliable units found in various theaters of operation. At times, their enthusiasm reaches such levels that it becomes challenging to control.

In any case, soldiers of the Roman era should not be envisioned as always displaying impeccable discipline. The Romans granted significant freedom to their men for heroic actions, as long as they benefited the collective. Honorary rewards were also stipulated for such endeavors.

The Shock of the Battle of Strasbourg

As Julien fortified his position, cries of indignation arose from the barbarian army. The troops feared that the leaders, mounted on horses, might take advantage of this position to abandon them in case of defeat. Therefore, the kings dismounted to stand alongside their men, fortifying their courage.

The trumpets then signaled the start of the battle. The violent clash of the armies ensued in extreme cacophony. The Roman line stubbornly resisted, opposing its coherence to the barbarian frenzy. However, on the right, Roman cavalry broke off the fight against barbarian horsemen and skirmishers.

Julien then moved forward to address this retreat and rallied the men who had regained their positions in the formation. The Cornuti and Bracchiates also demonstrated their great valor, impressing the enemy with their courage and indomitable bravery. At the climax of the battle, the Alamans managed to break the Roman line in the center.

However, the second Roman line intervened; the Primani Reges legion and the Batavi moved in support and repelled the danger. Ammianus, describing the battle, portrays the Alamans as equals to the Romans in war, perhaps to magnify Julien’s feat but also likely out of respect for the combative valor of the barbarians.

It is crucial to remember that a considerable proportion of the Roman army was populated by these barbarians, without exaggerating to the point of considering the entire army barbarized, which is untrue.

The Rout of the Barbarians

The violent battle continued in a quasi-stalemate, where, nevertheless, the barbarians were dying in greater numbers. Better protected and more professional, the Romans effectively contained the assaults of their enemies to the extent that they eventually dispersed and fled, pursued by Roman light units.

The carnage was significant, and the terrified barbarians fled in large numbers, swimming in the Rhine, where many drowned. Meanwhile, escaping the disaster, Chnodomarius had withdrawn from the battle with a few warriors, attempting to conceal himself on a wooded hill, when he was intercepted by a Roman cohort. Surrounded, he surrendered.

The losses in the battle were highly disproportionate and reflected the superior training and protection of the Romans. They left 243 troops and 4 officers on the field, while the Alamanni lost 6,000 on the field and an unknown number drowned in the Rhine. Ammianus is entirely reliable in the count, and his text leaves no doubt about the actual tally of losses.

The figures here closely resemble those of another famous battle, Marathon, where the Athenians also meticulously counted the dead, intending to perform a sacrifice for each fallen Persian. In that battle, 192 Greeks fell against nearly 6,400 Persians.

Battle of Strasbourg Epilogue

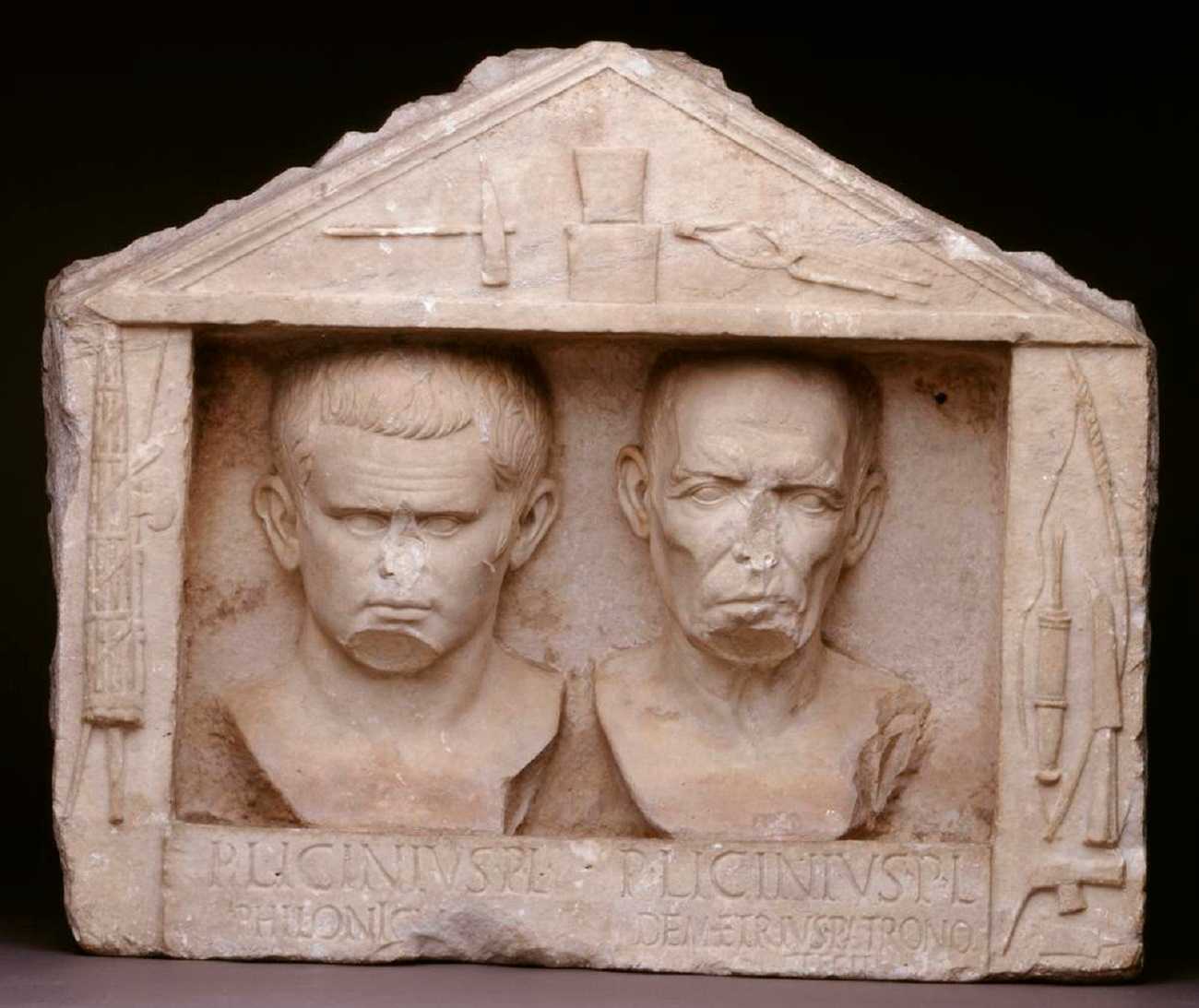

Following this battle, Chnodomarius is sent as a hostage to Rome, where he remains until his death. Julian, on the other hand, does not let his advantage slip away and takes the opportunity to launch bloody offensives on the territory of the barbarians, stabilizing the border permanently.

The Battle of Strasbourg is, in any case, a factor allowing us to gauge the tactical prowess of young Julian and his ability to transcend men. His saga is indeed significant, and he is never defeated in an open battle. His men will follow him even into the scorching sands of Persia, refusing to join Constantius II.

Adorned with the prestige of victory, Julian had become a victorious emperor, blessed by fortune, destined to break free from oppressive tutelage now that his men were entirely devoted to him.