From May 4–8, 1942, Anglo-American and Japanese troops engaged in a huge naval and air battle in the Coral Sea, one of the most significant naval and air battles of World War II. Already dominating most of the Pacific since Pearl Harbor, the Japanese set their sights on Australia and began positioning themselves for an invasion. To set the stage, on May 4, the Japanese began their onslaught in the Coral Sea. The Japanese drive towards the south was slowed as a result of this carrier action, marking a significant turning point in the conflict.

- The background of the Battle of the Coral Sea

- Australia under the Japanese threat

- The Americans in ambush

- A first “timid” engagement

- A game of hide and seek

- Martyrs and confusion

- Shoho: The first victim among Japanese aircraft carriers

- The last round

- The agony of the “Lady Lex” (USS Lexington (CV-2))

- Who won the Battle of the Coral Sea?

The background of the Battle of the Coral Sea

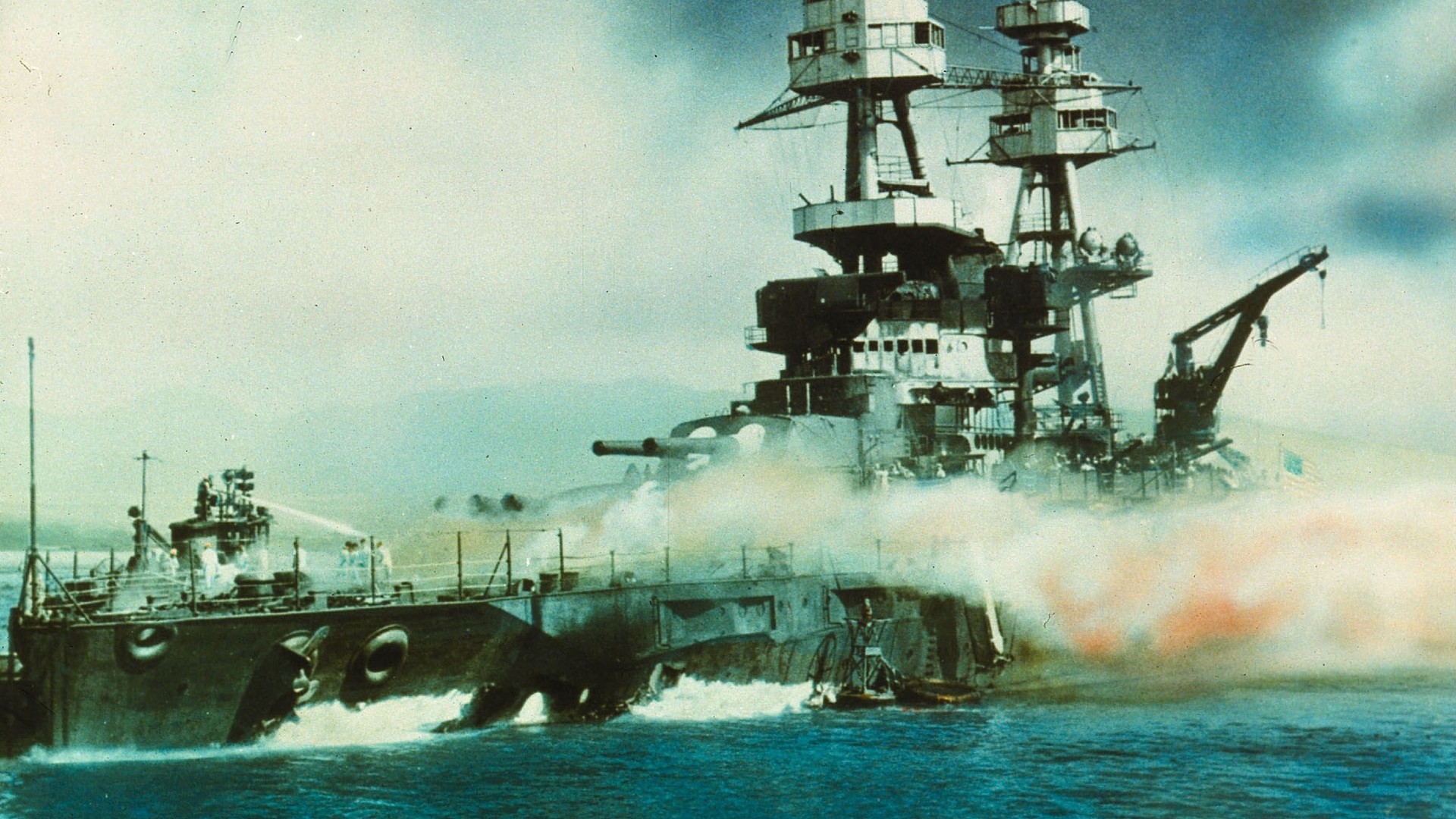

Following the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States entered formal war. With General MacArthur having abandoned Corregidor in March of that year, this was the first of many devastating blows that would continue until the end of 1941 and the beginning of 1942, when, among other things, the neighboring fall of the Philippines occurred. Even worse losses were sustained by the United States’ allies, particularly the British, when their strongholds in Southeast Asia fell one by one.

And yet, for all the drama of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese failed to take into account what would become the Pacific’s most important weapon: the aircraft carrier. When the Japanese attacked, none of the American aircraft carriers were even in the area. By the start of 1942, the United States was able to restructure and create a naval aviation force that could stand up to Japan’s might. This approaching fight would be unprecedented in every way imaginable: the opposing fleets would never be able to see one another, and the fate of the conflict would rest solely in the hands of the air force. The Battle of the Coral Sea began with these events.

Australia under the Japanese threat

Despite their astounding victories, the Japanese general staff was riven by infighting and rivalry between the Army and the Navy. To that end, Admiral Nagano wanted to push toward the West and India, whereas Admiral Yamamoto favored destroying the American fleet for good (and especially its aircraft carriers) in order to secure a favorable settlement. Once he had secured the Hawaiian Islands, Yamamoto planned to launch an assault on many fortifications, including Midway.

The army staff declined to provide Nagano with the resources he requested, so he developed a more modest plan to isolate Australia by seizing Port Moresby in Papua instead. Doolittle’s raid on Tokyo, however, met Yamamoto’s purposes, and in June of that year he was given permission to attack the island of Midway. Though the assault on Port Moresby was postponed from March to May due to the presence of American aircraft ships in the vicinity, the plans were never scrapped. The operation was named “Mo”.

The Americans in ambush

It was a tricky operation for the Japanese, who split their forces into two invasion groups (one for Port Moresby and one for Tulagi in the Solomons), a support group centered on the light aircraft carrier Shoho, and an assault force led by the huge aircraft carriers Zuikaku and Shokaku. Even though the Japanese expected stiff opposition, they believed the opposing naval force to be rather modest, with only the aircraft carrier Saratoga possibly present.

While the Americans learned about the plan through the decoding of the Japanese codes, the Japanese personnel had no idea. Admiral Nimitz recognized the importance of Port Moresby, and the fact that its loss posed a direct danger to Australia or, at the very least, its continued involvement in the war. On April 20, he knew this would be the target of the next Japanese offensive; however, he lacked the aircraft carriers Enterprise and Hornet, which were returning from the raid on Tokyo, and the Saratoga, which had been hit by a torpedo but was not yet out of commission (contrary to what the Japanese believed).

He then ordered the cruisers and destroyers to meet the aircraft carriers Lexington and Yorktown. The Lexington was the “sister ship” of the Saratoga (most of the battleships had been destroyed or damaged at Pearl Harbor). While Nimitz could only carry 150 planes at once, there were another 200 in the area, mostly in Australia, ready to help out in a pinch. He gave Fletcher leadership of the operation on April 29 and ordered him to the Coral Sea on May 1.

A first “timid” engagement

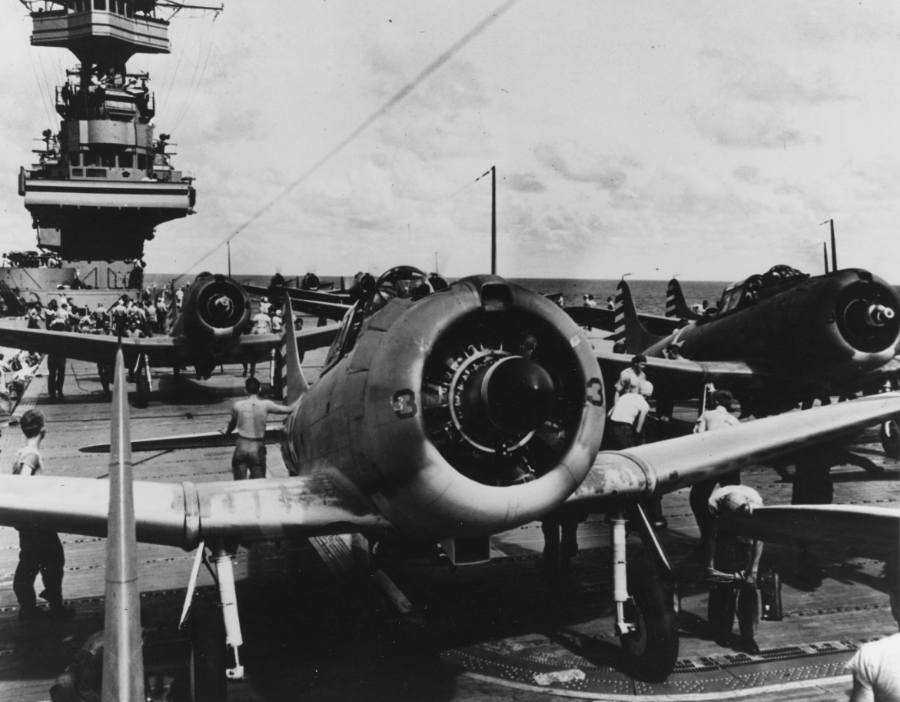

On May 3, American troops were still split and had little intelligence on enemy movements. The news that the Japanese had landed on Tulagi didn’t reach them until late that day. As a kind of retaliation, Fletcher then pointed the Yorktown directly towards the Solomon Islands. While the Japanese did not anticipate an assault, the American commander’s activities were well concealed by the cold zone. At 06:30 am on May 4, the aircraft of the Yorktown took to the skies, including 12 Devastators (torpedo boats) and 28 Dauntlesses (dive bombers), while the fighters stayed behind to guard the carrier.

As the inexperienced American pilots had never participated in a naval air strike before, there was a lot of misunderstanding, and the value of some ships was overstated. When they got back to the Yorktown at 9:31 am, they had only managed to sink three minesweepers and severely damage a destroyer. The Japanese lost just two seaplanes and four landing craft in two more raids. Nimitz called the American performance on Tulagi “disappointing,” even though they lost just three planes.

A game of hide and seek

Port Moresby was blasted on May 5, and the Coral Sea invasion by Admiral Takagi’s special unit “Mo” occurred only two days later. Fletcher arranged his combat formation the next day, splitting his cruisers into an assault group, a support group, and an air group, including his aircraft carriers. U.S. aircraft conducted surveillance missions, but they were unable to locate Takagi’s group. However, for some strange reason, Takagi didn’t give the order for any kind of far-off scouting.

The impending showdown was put off for a little while by this game of hide and seek, which was played out more or less voluntarily. The Shoho was only attacked by Australian B-17s, which, due to their bulky design, were ineffective against ships. Thankfully, they were able to identify the invading troop before it reached Port Moresby. Despite the enemy onslaught on Tulagi, the strategy continued as expected, giving the Japanese cause for optimism.

Martyrs and confusion

On May 7th, Admiral Takagi gave the order for further airborne exploration. He felt the timing was perfect since one of the planes saw what seemed to be an aircraft carrier and a cruiser; a tremendous assault was then launched; however, the plane’s targets turned out to be the tanker Neosho and the destroyer Sims. The latter sank while the former, the Neosho, managed to float in flames until May 11, when it was rescued by the destroyer Henley. However, the tanker had to be sunk to ensure the safety of the crew.

Even yet, the two American ships that gave their lives were not wasted. Earlier, at 06:45 local time, Fletcher had given the order for his cruiser group to begin fighting the Japanese invading force that had landed in Port Moresby. When the adversary opted to focus his land-based air units on the cruisers rather than his aircraft carriers, the American commander was really taking a chance. But the chaos persisted; the Japanese strikes were unsuccessful, and American B-26s almost sank their own ships.

Shoho: The first victim among Japanese aircraft carriers

At 8:30 am, the Japanese regrouped; they had seen Fletcher’s troop, and the Shoho was preparing an assault. At the same time, Fletcher sent out a reconnaissance mission, during which “two aircraft carriers and four heavy cruisers” were spotted at 8:15 am; the American squadron commander, mistaking these ships for those belonging to Takagi’s squadron, decided to dispatch 93 planes between 9:26 and 10:30 am. The reconnaissance aircraft flew back and changed their assessment once the strike force was in the air.

It would be as little as two heavy cruisers and two destroyers. It was too late to back out of the operation, and the major enemy forces were required to be in the region, so the aircraft would have to attack anyhow. True to Fletcher’s prediction, Dauntlesses from the Lexington discovered the Shoho at approximately 11 am and attacked it, followed by their compatriots from the Yorktown. The Shoho went down at 11:35 am after taking damage from thirteen bombs and seven torpedoes. The American ships and bombers were filled with jubilation as they had just destroyed the enemy’s first aircraft carrier of the war.

The Japanese were understandably enraged and decided to launch a counterattack that afternoon, launching from the aircraft carriers Zuikaku and Shokaku and bringing together a total of 27 of their top pilots. However, it was American radar that initially thwarted this response by allowing the ships’ interceptors to fend off an initial assault while the Japanese were delayed by poor weather. Then disaster struck; it was so unfortunate that it was almost comical: Japanese pilots mistook American carriers for their own on many occasions and were tragically shot down while attempting to land on their deck. Two-thirds of Takagi’s seasoned pilots perished on the mission’s first day of combat.

The last round

On the morning of May 8th, whichever side saw the other first would have the upper hand. They both saw each other at 8:30 in the morning, which was an issue. There were also comparable air forces on both sides, with the United States fielding 121 aircraft and the Japanese fielding 122. The weather, which was marginally better on the American side, was the only real difference.

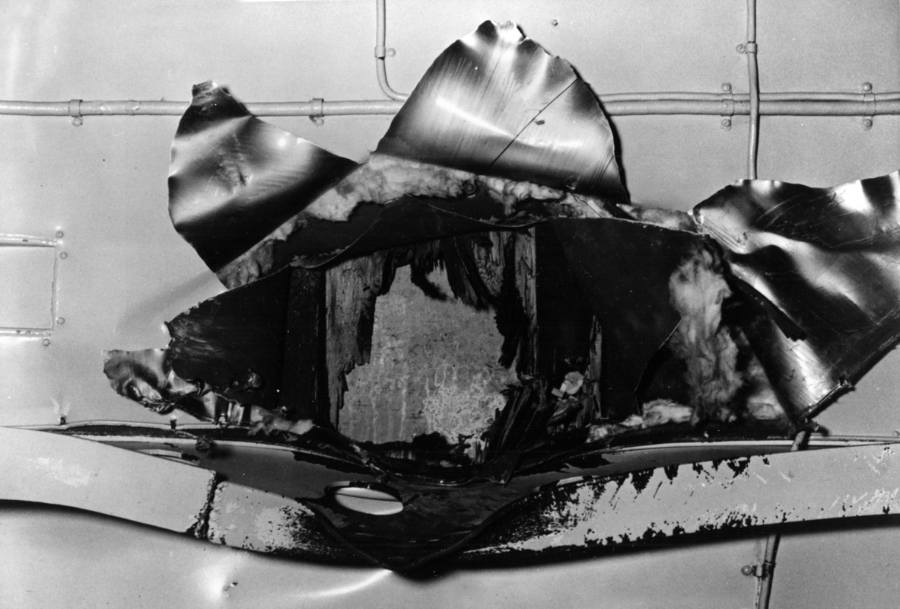

Dauntless bombers and Devastator torpedo boats began their attack on the aircraft carrier Shokaku at 10:57 am. The Zuikaku had hidden from the attack in a storm. While just two bombs seemed to have struck the carrier during the assault by Yorktown pilots, the damage was serious enough that the Shokaku could no longer launch aircraft. However, the assault by the Lexington’s crew ten minutes later was more decisive, and the Shokaku (Shōkaku) was forced to retreat to Truk after taking too much damage to continue fighting.

The agony of the “Lady Lex” (USS Lexington (CV-2))

So the Japanese were able to locate the American squadron in between their own two rounds of attacks on the opposing fleet, and they retaliated by bombing the Americans. When compared to their American counterparts, the Japanese pilots showed more skill due to their greater experience and participation at Pearl Harbor. At 11:18 am, they launched an assault on the two carriers; the more maneuverable Yorktown was able to evade eight torpedoes and sustain only minor damage from a single 880-pound (400 kg) bomb. On the other hand, the Lexington was caught between two waves of German torpedo boats and subsequently hit by four propeller bombs and two light bombs, one of which detonated in the ship’s ammunition storage area. The battle was over.

All of the pilots went back to their respective ships, and the Lexington’s damage seemed to be under control. However, at 12:47 pm and 2:45 pm, explosions occurred aboard the ship, rendering firefighting efforts futile. The call to abandon ship came about 4.30 pm. At 8 o’clock that night, the destroyer Phelps sank the “Lady Lex” with the aid of five torpedoes.

Who won the Battle of the Coral Sea?

The Japanese delayed their assault on Port Moresby despite hopeful reports from those on the ground. Because of this, Yamamoto became enraged and sent orders for Takagi to begin searching for American aircraft carriers, but by this time, Fletcher had already escaped.

Since the Japanese light aircraft carrier Shoho suffered far fewer casualties than the Lexington, the Neosho, and the Sims, the Japanese were able to claim victory in the combat on a points basis. Many of the Japanese fleet’s top pilots had been killed or captured, and the United States had the upper hand strategically. The Japanese onslaught on Papua was stopped short because of this first fight between aircraft carriers, and the resulting damage, especially the need to repair the Shokaku and to supply the Zuikaku, would have far-reaching consequences. Indeed, another much more important battle was to take place off Midway.

Bibliography:

- Willmott, H. P. (2002). The War with Japan: The Period of Balance, May 1942 – October 1943. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources Inc. ISBN 0-8420-5032-9.

- Woolridge, E. T., ed. (1993). Carrier Warfare in the Pacific: An Oral History Collection. John B. Connally (Forward). Washington D.C. and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-264-0.

- Parshall, Jonathan; Tully, Anthony (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-923-0.

- Peattie, Mark R. (1999). Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power 1909–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-664-X.

- Hoyt, Edwin Palmer (1986). Japan’s War: The Great Pacific Conflict, 1853 to 1952. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-030612-5. OCLC 185450652. OL 2542515M.

- Ito, Masanori (1956). The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1962 translated ed.). Jove Books. ISBN 0-515-08682-7.