On June 18, 1815, not far from Brussels, Napoleon Bonaparte‘s soldiers met the Anglo-Prussian troops of Wellington and Blücher at the Battle of Waterloo. Previously, on March 20, 1815, Napoleon reclaimed control in France (“Hundred Days”) after returning to Paris after escaping from the island of Elba, where he was imprisoned for 11 months. Russian, Austrian, Prussian, and British forces were swiftly sent to the Belgian border in order to initiate an invasion of France. Emperor Napoleon, with his 124,000 men, marched out to confront the foe. Waterloo was the primary confrontation of the battle, and Napoleon lost there, leading to the eventual collapse of the First Empire. Three armies participated in the Battle of Waterloo: Napoleon’s Army of the North (Armée du Nord), a multinational Anglo-allied army under Wellington, and a Prussian army under General Blücher.

- Background of the Battle of Waterloo

- A conflict with the Seventh Coalition is inevitable

- The battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras

- The Battle of Waterloo

- Seeking the improbable

- Grouchy’s role in the Battle of Waterloo

- When the Battle of Waterloo lost, the Napoleonic government lost

- The defense of Paris

- The legacy of the Battle of Waterloo

Background of the Battle of Waterloo

Meanwhile, Louis XVIII and his court reached Flanders, the escapee from Elba, Napoleon made a triumphant arrival in Paris on March 20, 1815, following a careful strategy of avoiding the most royalist districts. Rather then take him to Paris in chains, the soldiers joined him. The dignitaries of the Empire were there to greet Napoleon I as he alighted from his cart, and throughout Paris, tricolor flags waved proudly from every window as he was being carried up to the steps of Tuileries Palace by the masses.

Following Napoleon’s return to power in 1815, the Great Powers of Europe (Austria, Great Britain, Prussia, and Russia) proclaimed Napoleon an outlaw, and so the War of the Seventh Coalition had begun on March 13, 1815. Austria, the Netherlands, Prussia, Russia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and a number of German states formed the Seventh Coalition.

Emperor Napoleon’s return to power was met with celebration, but this should not obscure the serious challenges he was facing. Not all former Empire executives had come forth, and there were widespread suspicions that this imperial restoration was bound to fail. In an effort to keep the most dangerous ministers on his side, Napoleon restored Joseph Fouché’s police ministry, but politically, he needed to give pledges, especially because the Senate was responsible for his removal in 1814.

Napoleon especially aimed at liberalization; press freedom was restored (although he turned against it), and on April 6 his old adversary Benjamin Constant was given the task of writing a new constitution. In one week, Constant, who had just recently insulted Napoleon in the Journal des Débats, drafted a constitution that would define the new Napoleonic administration: a representative system with a wide electoral base, ministries answerable to the chambers, etc. Even the Chamber of Representatives was called to order by the end of May, and thus, the Additional Act to the Constitutions of the Empire had established a fully liberal system.

1,300,000 YES votes were cast in the 1815 French constitutional referendum, while only 4,000 NO votes were cast. While it was imperative to focus all efforts on the exterior threats, mainly the Seventh Coalition, Napoleon’s main goal was to avert an internal resistance (the Vendée region was already uprising) by supporting both the Royalists and the Republicans. Former National Convention (a French Revolution parliament) members like Bertrand Barère and other Revolutionary heroes like the Marquis de Lafayette were now serving in the new Chamber of Representatives.

At the forefront of this group was Jean-Denis Lanjuinais, a critic of Napoleon and one of the first to call for his overthrow in 1814. So, it’s not known whether Napoleon actually acknowledged his diminished power or if he saw this as a temporary compromise that he expected to revert to after the external threats had been eliminated and Napoleon no longer had any challengers at the head of his army. As such, Napoleon needed a swift military victory not merely to remove the foreign threat but also to destroy his political rivals at home.

Also, Napoleon had to reconnect with his troops and the people in order to get them back on his side. Louis-Nicolas Davout took command of the Ministry of War, which resulted in the recall of soldiers who had been disbanded during the Bourbon Restoration (1814), the conscripts raised in 1815 for Napoleon’s army, the restoring of the National Guards, the Imperial Guard, and the cavalry (to the letdown of the gendarmes, who were now forced to patrol on foot), and the formation and deployment of VIII Corps (Grande Armée) with a focus on the northern and eastern borders.

In order to counter the Seventh Coalition with the strength of 700,000, Napoleon planned to muster 800,000 soldiers by the end of the year. Napoleon Bonaparte also sorted through the marshals who hadn’t been faithful to him and reorganized the top of the army. By the end of it all, just Louis-Gabriel Suchet, Michel Ney, Louis-Nicolas Davout, and Jean-de-Dieu Soult remained under Napoleon, along with a newly promoted name, Emmanuel de Grouchy who will be decisive in the outcome of the Battle of Waterloo.

A conflict with the Seventh Coalition is inevitable

Along with this military display, Napoleon also wanted to detach his father-in-law, the Emperor of Austria Francis I, from the coalition, but Austrian Foreign Minister Metternich made it clear that they would never ally with Napoleon regardless. Napoleon suffered another setback in Italy when his key ally, the Napoleonic King of Naples, Joachim Murat, who previously betrayed him during the Fall of Napoleon in 1814, tried to take the Italian peninsula on his own to atone for his actions against Napoleon, but he was defeated by the Austrian army under Neipperg.

Thus, the peaceful rhetoric that Napoleon was attempting to convey to the Seventh Coalition countries was now broken as a consequence of Murat’s hasty move. It became clear to the coalition that a violent Napoleonic showdown was, in fact, imminent. On June 1, 1804, Napoleon organized a grand event in the Champ de Mai to mark his return.

Planning of the battle

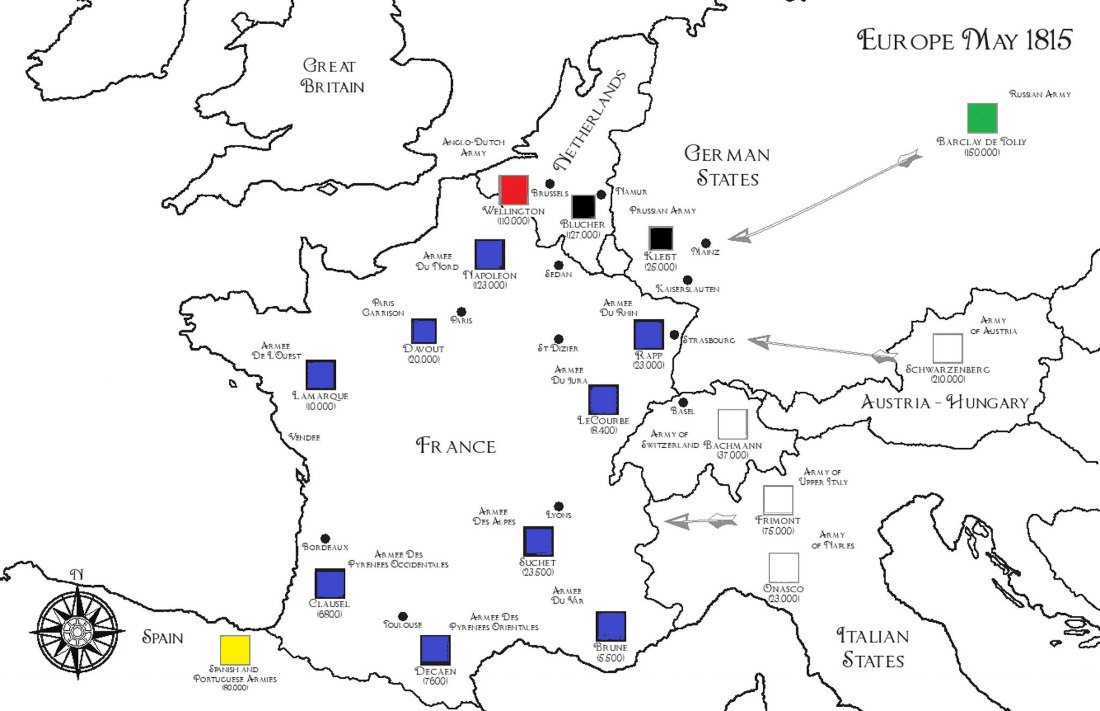

To impose himself on his political opponents while on his way to Paris, Napoleon wanted a decisive victory against an uncompromising external threat. A number of campaign plans were proposed against the Seventh Coalition, including an April assault, then a defensive battle in Paris and Lyon, or an offensive in June. Napoleon decided on the latter. Because Brussels was surrounded by the Duke of Wellington’s Anglo-Dutch forces, Namur by Blücher’s Prussians, and Moscow and Vienna were too far away to help them.

If Napoleon were to launch an offensive in June, he could be able to catch Wellington and Blücher’s Prussians off guard before they launch an assault first. If Napoleon were to win decisively over these two armies, it wouldn’t be the last of the Seventh Coalition (the Austrians and Russians would still be standing), but he believed it would be enough of a shock to get them back to the negotiation table as soon as possible.

And if the offensive approach against Paris and Lyon were to fail, the defensive strategy was always an option. To prepare for this possibility, Napoleon stationed 25,000 more soldiers in Alsace to confront the Austrians. It has been argued that this extreme caution by Napoleon was a mistake since it prevented him from committing the whole force of the Empire to the decisive Battle of Waterloo in Belgium.

On June 14, Napoleon arrived in Belgium with 124,000 men and 370 cannons. His plan to defeat Wellington’s 95,000 soldiers and 186 guns with the Prussians’ 124,000 soldiers and 312 cannons was to separate their forces to compensate for the significant numerical deficit.

The French army crossed the Sambre River in three columns on June 15, 1815, after having successfully surrounded the city of Charleroi in Belgium and driven out opposing detachments. Napoleon’s plan was to strike at the Prussians first, as they might threaten his flank if the British intervened on their side. As the French General Grouchy repelled the Prussian advance at Fleurus, Napoleon sent Marshal Michel Ney to Quatre Bras to hold the British.

The battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras

On the night of June 15–16, the Duke of Wellington realized that the French assault was primarily directed against the Prussian army. He devised a plan to shock the French forces by having the Prussians act as an “anvil,” keeping Napoleon’s soldiers pinned down around Ligny, and allowing Wellington to land the “hammer.” The British struck the French flanks at the Battle of Quatre Bras while Napoleon and Grouchy marched to confront the Prussians at the Battle of Ligny.

With the oppressive heat and humidity, Napoleon decided to make an assault on the Prussian center while expecting Ney to take the Quatre Bras and then strike the Prussian flank. But under the command of Wellington, the British resisted, and Ney failed to take the Quatre Bras in time. It was now too late for Ney to help Napoleon.

Marshal d’Erlon’s corps might have played a crucial role that day, but they were stuck between the battles due to the conflicting instructions of Napoleon and Ney, and thus they ended up not fighting in either.

The day ended with the Prussians being defeated by Napoleon but not destroyed. Prussian General Blücher was thrown to the ground by the Imperial Guard and Baptiste Milhaud’s cuirassiers. He was knocked unconscious while the French cavalrymen rode right by him, and he spent the next ten minutes laying behind the French lines until riding back to join his army on a British Dragoon Guard’s horse. Wellington withdrew to the defensive position of Mont-Saint-Jean in Belgium, the last open ground for battle before Brussels, before the Soignes Forest, while the Prussian army retreated to Wavre. The Prussians lost between 12,000 to 20,000, killed or wounded, compared to 6,500 to 8,500 on the French side.

Napoleon later said that Wellington had made a poor decision by deciding to fight in this area since he could not have made a well-planned escape via the woodland massif had he been defeated. Napoleon continued his advance on the 17th, this time heading for Mont-Saint-Jean, and gave Grouchy and his 30,000 soldiers the mission of pursuing the Prussians.

Napoleon pictured several possibilities, but his instructions were still vague about how to act. It was also unclear to Grouchy whether Blücher would choose to join Wellington or withdraw to his lines of communication to the east. The French were right behind the English rearguard, cannoning them with artillery and sabering with cavalry. Even worse, violent thunderstorms broke out in the area, soaking the sunken roads and fields. These storms proved invaluable to the defenders, as they delayed Napoleon’s assault on June 18 and weakened the French artillery as cannonballs sank in the mud rather than ricocheting through the enemy ranks.

The Battle of Waterloo

The Anglo-Dutch-Belgians had 85,000 troops on the day of the conflict, minus the 17,000 detached, for a total of around 68,000 men and 184 guns. There were 127,000 Prussian soldiers. The French, however, fielded just 74,000 soldiers and 266 guns for the Battle of Waterloo.

The British army was poised for war on June 18, 1815 at first light. Wellington had taken a defensive stance. He deployed his men along the whole 1,9 miles (3 km) of Mont-Saint-Jean, hiding them slightly below the ridge line from the heavy French guns. British artillery was stationed atop the ridge, ready to rain destruction down on any infantry columns that dared attempt to scale the plateau. Finally, Wellington positioned soldiers around three farmhouses on the hill to break the momentum of these assault columns: the Hougoumont farm on the British right-wing (to the west), the La Haye Sainte farm in the middle, and the Papelotte farm on the left wing (to the east).

Almost half a mile to the south, the French soldiers awoke. Yes, the French troops, like the rest of the Seventh Coalition, had slept outside in the rain. Napoleon and his staff ate breakfast together at the Caillou at 8:00 in the morning. Charles Reille, who had fought with Wellington in Spain (Battle of Vitoria), strongly advocated against a frontal assault because of Wellington’s policy of relying on artillery via relatively thin infantry lines. However, a frontal assault was part of Napoleon’s strategy; after waiting for the sodden terrain to dry up a little due to the weather, he was planning to make an attack on the enemy center with his strong artillery. Just like at Ligny, the temperature quickly got hot and humid.

It wasn’t until 11.30 a.m. that the cannonade began, and it wasn’t particularly effective since the French guns were so far away (around 4,000 ft or 1,200 m) and most of the British forces were hidden behind the ridge. When Napoleon gave the order to assault the Hougoumont farm in order to distract the British army before attacking the center, his brother, Prince Jerome, operated this initial assault. The position was defended by a Scottish Lieutenant-Colonel, James Macdonnell, who was in charge of 200 Coldstream Guards and 1,000 Germans from Nassau. The fighting was ferocious. The defenders had constructed a fortification around the farm, complete with a wall 6,5 feet (2 meters) high that is riddled with small gaps just like a castle.

Lieutenant Legros of the “1st Léger” was able to use an axe to smash through the southern gate and lead a small group of French soldiers into the farm’s fence, but the defenders quickly reopened the gate and slaughtered them. The French left wing wasted their time attempting to capture this secondary objective as Wellington dispatched troops to protect the farm. The defenders lost just 1,000 men during these attacks, while 5,000 Frenchmen died. The British referred to the area in front of the farmhouse as the “killing ground” because of the large number of bodies that had been left there.

When the first part of the fight was over, Napoleon moved on to the second phase, which included attacking the heart of the enemy’s defenses. Napoleon had General Grouchy retreat because the first Prussian forces were already spotted. Starting at 1:30 p.m., the French infantry launched an assault on the Prussian center, beginning with a furious artillery duel that drove the Dutch-Belgians up the hill and onto the plateau and the defenders of the La Haye Sainte into a defensive encampment. Knowing Wellington’s firepower-based plan, General d’Erlon avoided forming compact columns in favor of extended lines. Wellington’s left flank was threatened when General Durutte advanced all the way to the Papelotte farm.

But the British (consisting of veterans of the Spanish War) and Hanoverian forces halted the French attack on the ridge by bombarding the exhausted grognards (Napoleon’s Imperial Guards) who had just scaled the plateau. British General Thomas Picton even tried to mount a counterattack, but a musket ball shot him in the head. Wellington’s 1st and 2nd Life Guards, assisted by General Ponsomby’s Dragoon Guards, swooped down on the French General Marcognet division and forced it back to capture the left flank.

However, the British cavalry, initially failed in discipline, later caught in the momentum of the Royal Scots Greys cavalry, and continued their push despite the order to withdraw, sabering the French artillery before being caught in a pincer movement by the lancers of Martiguez and the Cuirassiers of Jacques Travers and suffer heavy losses. General Ponsonby was wounded by a spear but survived with the help of a French soldier.

With the French central assault failing, the Battle of Waterloo entered its third phase at approximately 3:30 p.m., when French artillery began bombarding the La Haye Sainte in preparation for an attack. Several German battalions retreated for cover, but Ney mistook this action for a massive withdrawal. At 4 p.m., he ordered his cavalry to launch a full-scale attack on the enemy’s central stronghold, with Milhaud’s Cuirassiers leading the way. Wellington’s core and right flank saw the gleaming mass of army approaching and organized into around thirty squares in four rows, forming walls of bayonets against the cavalries of the French.

These infantry squares were fortified by British artillery, which answered the arrival of the French cavalry with deadly fire. Next came the salvos of the infantry, who were provoked to maintain their ground by commanders yelling from the heart of the squares. The batteries were overrun, but although Ney led ferocious attacks for two hours, the British squares held firm. These valiant attacks ultimately failed catastrophically, and Napoleon was frequently blamed for not launching the troops to back up Ney’s cavalry. The remnants of the British cavalry, led by the Earl of Uxbridge (Henry Paget), gave pursuit to the fleeing French.

Nonetheless, the French infantry was far from idle. The French troops in the southeast were about to confront the approaching Prussians under Friedrich von Bülow, who was closing in on the French Imperial Army’s rear. On the front lines, no one was told about this dreadful news, but they were informed that French General Grouchy was on his way for support. At 6 p.m., combat broke out in the village of Plancenoit, forcing Napoleon to call in the Young Guard, assisted by two battalions of the Old Guard, and ultimately retaking the village of Plancenoit for the French. The French leader Quiot and his troops stormed the Sainte Farm and took it when the defenders ran out of ammunition, as Napoleon had instructed Ney to do so. With the farm’s seizure, French artillery was able to move closer to the British center to unleash a bombardment.

On the other hand, French General Durutte dealt significant damage to the British left flank. Wellington’s situation was dire; his defenses were about to collapse, his cavalry had been wiped out, his supplies were running short, and the Cumberland Hussars had already abandoned the field. “Night or the Prussians must come!” the British commander cried out in desperation. The night was still hours away, but Napoleon knew the Prussian threat was real. The battlefield situation had deteriorated to the point of paralysis, and Napoleon was unable to deploy the reinforcements Ney had been pleading for. Napoleon formed a square with his men on the route to Brussels and sent the Guard to clear Plancenoit.

Seeking the improbable

Then Napoleon could either move back while his Imperial Guard covered the retreat, or he might risk all in a last attack. But Napoleon could only try option two because of the political and strategic need for a victory. At 7 o’clock in the evening, the Imperial Guard launched its last attack, sending 9 battalions to the plateau to clear it of enemy forces. Similarly, Wellington hastily rushed to bolster his center with all of his available reserves. Ney routed the assault columns in the same direction as the cavalry, leaving them vulnerable to the artillery, whereas taking the road to Brussels would have been a safer option. Napoleon’s Imperial Guard advanced in a line up the ridge, showing off their hard training. But after taking a deadly barrage from the British 5th Brigade, the Imperial Guard initially halted but later drove the defenders back.

The British defenses were on the verge of collapse, but the arrival of the Dutch reinforcements on the second line actually stabilized the situation. And after taking heavy damage from British artillery and the subsequent salvo fire, the Imperial Guard withdrew for the first time in its history. The remainder of the Guard, facing the British, was also wiped out by the salvo fires dropped at about 82 ft (25 m). British Colonel John Colborne placed his soldiers in a long line to the left of the French onslaught, giving them an unobstructed field of fire that annihilated the Imperial Guard.

With shouts of “The Guard retreats. Run for your life!” spreading panic through the French lines, the French fled to the base of the plateau, and Wellington ordered his forces to advance. After having five horses killed beneath him during the combat, Ney yelled to the British 95th Regiment, “Come and see how a Marshal of France meets his death!” Napoleon and his three battalions of Old Guard were positioned around 330 feet (100 meters) from La Haye Sainte. Several memorialists, including the well-known Jean-Roch Coignet, attested to Ney’s desperation and desire to die on the battlefield.

Napoleon, giving up, retreated toward La Belle Alliance. The French General Cambronne confronted the English while they invited him to surrender. He famously, and allegedly, answered the English by saying “The Guard dies, it does not surrender.” The village of Plancenoit was still held, but the battalions couldn’t stand any longer against the British army corps. The withdrawal was ordered by Napoleon. The only orderly retreat was made by the Old Guard, who formed two squares and moved backward at a walk. Plancenoit fell to the Prussians at 9 p.m., and Blücher and Wellington met up at La Belle Alliance. Blücher wanted this place to become the name of the battle, but Wellington preferred the village of Waterloo, where his headquarters were found.

The Battle of Waterloo shattered Napoleon’s reputation forever. According to scholars, Napoleon suffered from painful hemorrhoids since the beginning of the Battle of Waterloo, which stopped him from riding his horse to properly survey the battlefield. But obviously, given the Battle of Waterloo’s outcome, these factors cannot account for the loss on their own. The retreat turned into a debacle. Napoleon lost his ceremonial coat, his treasures, and one of his hats.

“Take no prisoners!” That was the Prussian order. 20,000 French soldiers were killed or injured, including seven French generals. Roughly the same number of Coalition soldiers were killed or injured on the opposing side. This number included 7,000 Prussians. The remaining French troops marched towards Charleroi and then Paris through Laon.

Grouchy’s role in the Battle of Waterloo

Napoleon and his generals blamed Emmanuel de Grouchy for the loss of the Battle of Waterloo. His inexperience, slowness to respond, and lack of initiative were held against him. Gerard had ordered him to “march to the sound of the guns” at Waterloo to help Napoleon, but he had intentionally held his soldiers back and not joined Napoleon.

While Napoleon fought at Mont-Saint-Jean, Grouchy went for the Blücher’s Prussians instead, foolishly believing he was still completing his order of stopping the Prussians to join forces with the British. But in reality, Grouchy had faced just one Prussian corps at Wavre instead of four, which the Saxon Thielmann left behind. It was 6 p.m. on this pivotal day when he finally realized it.

Since Grouchy failed to hold Prussians back at the Wavre, Napoleon’s army was overwhelmed at Waterloo with Wellington and Blücher’s forces joined together.

Thielmann had accomplished his goal of keeping Grouchy away from the Battle of Waterloo by successfully blocking him in the city of Wavre. The new order that Grouchy received on the 18th was not clear either. It ordered him to continue the combat in Wavre and at the same time to pursue the Prussians toward Waterloo. It was written in pencil and was partly illegible, so no one could tell whether or not the battle had been “engaged” or “won” in Waterloo. Because it would have taken 3 hours for the 1 a.m. order to reach Grouchy, some argue that Grouchy would not have been able to close the 9.3-mile (15-km) gap between himself and Napoleon before the battle in Waterloo ended.

Once the Battle of Waterloo was finally lost, Grouchy was given the command to return to France through Namur. Grouchy at least deserves recognition for safely returning his army to French soil without losing a single member of his unit.

When the Battle of Waterloo lost, the Napoleonic government lost

Within 10 days, Napoleon aimed to muster enough soldiers to mount a defense, as previously planned. Napoleon wanted to assemble 80,000 to 100,000 troops if he could rapidly rally the corps of Grouchy, Jean Rapp, and the Army of the Loire. Enough to delay the coalition forces for long, Napoleon raised a tremendous army, bringing the total number of soldiers fighting for him to 800,000. To expand his constitutional dominion, however, he needed the support of the deputies. But, he had no idea that Joseph Fouché (the Minister of Police), having learned about the Waterloo defeat on June 19, was already attempting to persuade the deputies that Napoleon must abdicate.

Napoleon regrouped his army around the city of Philippeville and gave the command to Jean-de-Dieu Soult while Emmanuel de Grouchy was still fighting at Wavre. Napoleon then went ahead to organize the defense of Paris as he knew that he could only have an influence on the deputies if he stood there in Paris during the invasion.

The Napoleonic forces were successful in their operations in Belgium against the Vendée insurgents (War in the Vendée), and in the East, Marshal Suchet repelled the Piedmontese attack and advanced on Geneva. After all, there was still hope. Although his brother Lucien was a skilled politician, Napoleon was unable to maintain the support of the Chambers. Attempting to seize dictatorial power to oversee the last stages of the campaign, he still failed.

Lucien Bonaparte insisted that dissolving the Chambers was the only option, but Napoleon was uninterested, and the Chamber had proclaimed that any effort to do so would constitute high treason.

Lazare Carnot advised Napoleon to proclaim a national emergency and mobilize the National Guards in order to regain the momentum of 1792 and 1793 and to fortify his position behind the Loire River in preparation for a counterattack. However, Napoleon’s advisor, Caulaincourt, explained that all would be for naught if Paris were to fall.

There was still a strong sense of patriotism and will to resist in Northern and Eastern France, where students as young as sixteen were forming artillery companies, including units of snipers called “francs-tireurs” like Colonel Viriot’s “Corps Francs,” who flew a black flag with a skull and crossbones bearing the words “The Terror precedes us. Death follows us.” Patriotic support was actually on the rise, even in historically unsupportive areas like Puy-de-Dôme, where people donated harnessed horses to the army.

Although only partially, France appeared capable of rising against the Seventh Coalition Army. While the general uprising had its benefits, it also had its drawbacks. The federal associations that were previously formed had brought together not only the Bonapartists but also the “Patriots of 1789” and “Terrorists of 1793,” who were committed to preventing the Bourbon Restoration, but they were not loyal to the imperial monarchy either.

And added to all this, the majority of French people were actually weary of the conflicts of the Revolution and the Empire, and they were desiring peace quickly. There was reluctance to deploy mobile guards in several areas, including Ariège, Haute-Loire, and Oise. Having been burned by 1814, the France of 1815 was quite different from the France of 1792. The peasants had fled before the approach of the Seventh Coalition, and the cities had not put up a violent opposition. Worse, not only in the Vendée but across the country, there was outspoken royalist support. Some royalists were already plotting a tyrannicide behind the scenes to assassinate Napoleon; provincial lords were bribing the mobilized troops, and businesspeople were even hoping King Louis XVIII would return so that they could resume profitable commerce with England again.

Napoleon was unable to enforce military recruitments in the face of widespread opposition; inexperienced prefects had been appointed during the political cleansing of the Hundred Days, and many royalist mayors had been allowed to stay in post in the communes.

Napoleon’s political situation had stalled, and Fouché was already making plans for the post-Empire era. The Chamber of Representatives granted itself sovereign rights and forced Napoleon to abdicate or face a coup.

In the face of the civil war threat and despite the support of a portion of the Parisian population that came to demonstrate its love for Napoleon in the vicinity of the Élysée, Napoleon, not wanting to turn into the “King of a Jacquerie” (a popular revolt of the 14th century), abdicated on June 22, 1815, withdrawing to Château de Malmaison.

Then, Carnot, Grenier, Caulaincourt, and Quinette formed a temporary government, with Fouché as their leader. Although Napoleon’s son Napoleon II was the disputed new Emperor of France, Fouché already had the support of the English on the capitulation of Paris and the restoration of the Bourbons.

The defense of Paris

The march of the Seventh Coalition to Paris was littered with battles, some of which went in favor of the French but which had since been forgotten due to the lack of strategic significance in the shadow of Waterloo’s devastating defeat. On June 20th, Grouchy won a decisive victory against the Prussians, who had been tailing him for too long.

Le Quesnoy, guarded by the National Guard, fell to the Coalition forces on the 26th. On the 27th, d’Erlon gained a decisive victory against Ziethen’s Prussians at Compiègne, while Bülow took both Senlis and Creil. After the Coalition soldiers prevailed on all fronts on June 28, Blücher planned to assault Paris from the north on June 30 as they were around 30 miles (50 km) away from the capital. But after being driven back by the Parisian defenses, Blücher regrouped to the west and south of Paris.

Food and ammunition were not an issue for Davout in Paris, and he was confident in his ability to resist Blücher. Nonetheless, Davout was well aware of the immediate need for a second restoration of Louis XVIII. He sent Isidore Exelmans’ second cavalry corps to quell the Prussians’ will. There were 16 Dragoon, 6 Hussar, and 8 light Imperial Guard cavalry squadrons along with the 4 battalions of the 44th Line Infantry Regiment ready for a charge.

Colonel Sohr’s brigade was smashed by Exelmans’ surprise attack on their way to Vélizy, where they had a numerical advantage of seven to one (about 5,000 to 750). After losing the fight, Colonel Sohr and 300 of his troops were captured.

After the Prussian vanguard was defeated at Rocquencourt, the Belgium campaign came to an end three days later with the signing of an armistice. However, the war in France continued, and the Château de Vincennes was not given up until November 15, 1815, when General Daumesnil agreed to do so.

For his part, Napoleon traveled to Rochefort after proposing, in vain, to assume command of the Government Commission’s armed forces as a mere general. For a long time, Napoleon had hoped to be able to escape into exile in America, but on July 3 he found out that he had been denied and the British navy was blocking the coast. Since Napoleon knew that Fouché might hand him to the royalists, he surrendered to the English in the hopes that they would be more forgiving. Napoleon waited on the Island of Aix as Louis XVIII entered Paris on July 8, marking the second restoration of King Louis XVIII. On July 14, Napoleon embarked on the Bellerophon and made his way to Plymouth before setting sail for Saint Helena, the burial place of the Emperor, where Napoleon died from stomach cancer on 5 May 1821.

The legacy of the Battle of Waterloo

Within a short time, the Battle of Waterloo had become a cultural touchstone, remembered by every participant. And thus, on June 18th, Wellington held a feast to celebrate the triumph, which continued until 1857. Waterloo has been honored by the naming of several public structures, including barracks and a well-known London Waterloo Train Station.

Napoleon’s final battle, the Battle of Waterloo was as brutal as it was spoken about. The accounts of the combat were recorded in the memoirs of the participants, such as Marcellin Marbot. In addition, Napoleon’s own account of his failed political endeavor in the Belgian lowlands was published in 1823 in the Memorial of Saint Helena. This imperial epic worthy of the ancient tragedies became the bedtime reading of a generation of young romantics bored by the blandness of their own era.

Despite being a staunch royalist and previously a firm enemy of Napoleon, the writer Chateaubriand became a passionate supporter of Napoleon and delivered the narrative of how he went through the Battle of Waterloo. Victor Hugo succeeded Chateaubriand in continuing to deliver more Napoleonic memories. Exiled following Napoleon III’s coup in 1853, Hugo composed the most beautiful verses and, perhaps, the most renowned lines about the Battle of Waterloo in his Les Châtiments (“Castigations”):

Waterloo! Waterloo! disastrous field!

Like a wave swelling in an urn brim-filled,

Your ring of hillsides, valleys, woods and heath

Saw grim battalions snarled in pallid death.

On this side France, against her Europe stood:

God failed the heroes in the clash of blood!

Fate played the coward, victory turned tail.

O Waterloo, alas! I weep, I fail!

Those last great soldiers of the last great war

Were giants, each the whole world's conqueror:

Crossed Alps and Rhine, made twenty tyrants fall.

Their soul sang in the brazen bugle-call!

—Les Châtiments ("Castigations,") translated by the English poet and translator Timothy Adès

After going out of his way to visit the battlefield of Waterloo in 1861, Victor Hugo wrote a collection of poems named “The Legend of the Ages,” which included “The Emperor’s Return.”

Erckmann-Chatrian‘s most popular historical fiction, Waterloo, was published in 1865 during the Second French Empire, which followed the previous Histoire d’un Conscrit de 1813 (The History Of A Conscript Of 1813). They added a touch of epic and reality to this work in a style that has been defined as rustic realism, in which basic and familiar individuals become heroes of the epic.

Among the founders of realism in European literature, Balzac also planned to write on the history of the Napoleonic Wars and the tragic myth of Waterloo.

Bibliography:

- The Champ de Mai · Napoleon’s 100 Days

- David Hamilton-Williams, (1993), “Waterloo New Perspectives: The Great Battle Reappraised.”

- J. Christopher Herold, (1967), “The Battle of Waterloo.”

- Victor Hugo, (1862), “Chapter VII: Napoleon in a Good Humor”, Les Misérables.

- Brown University Library, “Napoleonic Satires.”

- Bernard Cornwell, (2015), “Waterloo: The History of Four Days, Three Armies and Three Battles.”