When the twentieth century began, China was suffocating beneath the weight of the major Western powers. To be sure, the nation was compelled to open up economically, politically, and spiritually to other countries following the Opium Wars and the Sino-Japanese War. In addition, a secret organization, whose members were termed “Boxers” by Europeans, revolted in 1899 in an effort to free the nation. The growth of Chinese nationalism would hasten the fall of the Qing dynasty’s Manchu monarchy and bring about more foreign involvement in China.

Why did the Boxer Rebellion break out?

The Manchu Empire’s economy went into a deep slump in the middle of the nineteenth century, mostly because its administration had not kept up with the changing demographics and had instead stuck to its old ways.

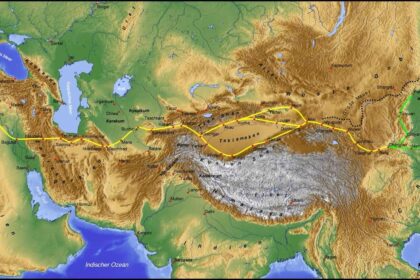

As the rest of the world was swiftly modernizing, China retreated inside, clinging to practices and institutions that were hundreds, if not thousands, of years old. Canton was the only place in China where trading with other nations was legal, and even then, only if a Chinese firm was involved.

What were the causes of the Boxer Rebellion?

After fifty years of unfair treaties between the Chinese Empire and foreign countries, the Boxer Rebellion broke out. In 1839, the emperor of China was so concerned about the impact of opium on his country’s people that he had British supplies in Canton destroyed. As a direct result, the British immediately began attacking, setting off the First Opium War.

China was ultimately defeated in the war, and as part of the Treaty of Nanking, five of its ports were opened to international commerce, and Hong Kong was ceded to the enemy. However, despite these benefits, the British were not content, and thus the Second Opium War erupted in 1856.

After being beaten this time, China agreed to let Christian missionaries and international delegations set up shop in 11 previously closed ports. As a result, a war was being planned against Japan while China, already weakened by the Taiping insurrection (1851–1864), found itself more influenced by the West. As expected, Japan has progressed and become more advanced.

Thus, it did not think twice before attacking its neighbor to assert its supremacy over Korea. In April 1895, China signed the unfavorable Treaty of Shimonoseki, ceding even more territory to its enemies. The Movement of the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists, or the Boxer Rebellion, emerged from this time of crisis, submission, and discontent among the Chinese people.

Why did the Hundred Days’ reform fail?

At the conclusion of these wars, the Russians, the French, the Germans, and the English split up China into spheres of influence. In light of this embarrassment, the youthful emperor Guangxu surrounded himself with reformist intellectuals.

They convinced him that the only way the Empire could survive was to modernize. Although their changes were based on Western ideals, they were not well received by Empress Cixi or many other court officials.

They were set in their ways and would have none of the Western ways being imposed upon them. Cixi staged a coup d’état and had the emperor locked up to put a stop to the uprising. This period is called the Hundred’ Days Reform. Guangxu was imprisoned at the Summer Palace when the empress took over regency, and he died there in 1908.

How does the Boxer Rebellion start?

The Boxer uprising was sparked by the empress’s actions and the ensuing indignation at the country’s disintegration. Boxers, as they were dubbed by Westerners due to their participation in holy boxing, were members of the Yihetuan, a secret organization (“Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists”). Invading foreign delegations and missions at Cixi’s covert request, they murdered clergymen and ultimately the German envoy, Clemens von Ketteler, in June of 1900. The imperial authority soon declared war on the Westerners and publicly backed the uprising.

What was the reaction of the Western powers to the Boxer Rebellion?

Germans, Italians, French, English, Austrians, Russians, Americans, and Japanese quickly assembled an invasion force. The forces, led by the German von Waldersee, recaptured Tianjin with relative ease and then marched on to seize Peking on August 14, 1900. The insurrection was put down after 55 days, and the empress and her court departed the city.

What were the results of the Boxer Rebellion?

On September 7, 1901, the imperial government signed the Peking Protocol, agreeing to compensate the Western countries to the tune of 450 million taels (about 1.6 billion gold francs) for their involvement in the revolt. The popular Boxer insurrection, which had its roots in resistance to Western economic colonialism, ultimately failed.

For China, whose economy became more dependent on Western aid, the consequences were disastrous. The Qing dynasty’s reputation was damaged even more as a result of this occurrence. All the government changes that followed were too little, too late for China, and the traditionalists and the conservatives who had been the backbone of the country’s politics for so long. It was 1911, and the revolution was about to begin.

TIMELINE OF THE BOXER REBELLION

17 April 1895 – Treaty of Shimonoseki

In the Treaty of Shimonoseki (Japan), China accepted defeat after a short war with Japan. As a result of this pact, China gave up some territory in South Manchuria, the Pescadores, and the island of Formosa (later called Taiwan). In addition, it acknowledged Japan’s de facto rule over Korea and paid hefty indemnities to the defeated nation.

At the time, Japan was planning an assault on Russia in retaliation for Russia’s obstruction of Japan’s colonial ambitions. The stage for the twentieth century’s major conflicts was set in Asia. Starting next year, the area would be divided into zones of influence by the big powers (France, Russia, the UK, and Germany).

June 11, 1898 – Beginning of the Hundred Days’ Reform

Throughout his reign as China’s emperor, Guangxu was advised by a group of reform-minded scholars and intellectuals. In an effort to fight European countries’ attempts to divide China into zones of influence, these reformers overhauled the country’s government, schools, and economy.

These changes, which took their cue from Europe, were a huge snub to Empress Cixi, who saw them as too conventional and anti-Western. With her considerable court power, she stymied her nephew and emperor’s initiatives while secretly supporting the work of groups like the Yihetuan, or “Boxers.”

June 20, 1900 – Boxer Rebellion in Beijing

As a result of the presence of foreigners in China, members of the secret organization Yihetuan, “Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists,” also known as “Boxers,” rose up in rebellion. Invading Catholic missions, besieging embassies, murdering priests, and ultimately taking the life of the German envoy, von Ketteler, were all tactics used by these men.

The colonial powers that had been in China since the Opium War of 1840 responded swiftly, prompting the departure of Empress Dowager Cixi from the capital.

July 14, 1900 – The Western army recaptured Tianjin

When the Boxer Rebellion broke out, the world powers with economic ties to China banded together to send an expeditionary force led by the German General von Waldersee to put down the uprising.

French, American, British, Russian, Austrian, German, Italian, and Japanese soldiers were also there. As an added bonus, the alliance faced little resistance when they invaded Tianjin on July 14, 1900. A month later, it would invade Beijing and put a stop to the uprising.

August 14, 1900 – End of the Boxer Rebellion

A multinational expeditionary army led by German commander Alfred von Waldersee landed in Tianjin and eventually captured the Chinese capital. After 55 days, it ended the siege of the European embassies in China by the Chinese nationalists.

The uprising that had begun against the alien presence two months earlier had finally come to an end. Cixi, the imperial grandmother, and her entourage escaped. However, a massive war indemnity was imposed on the imperial administration.

September 7, 1901 – China must compensate foreign powers

After the Boxer Rebellion gained momentum, the imperial government of China was pressured into accepting the terms of the Peking Protocol.

It had to make hefty compensation payments to hostile governments. Overall, the Boxer Rebellion hastened the downfall of the Manchu monarchy and increased China’s reliance on Western powers.

Bibliography:

- Esherick, Joseph W. (1987). The Origins of the Boxer Uprising. U of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06459-3. Excerpt

- Thompson, Larry Clinton (2009). William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris, and the “Ideal Missionary”. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-78645-338-2.

- Harrington, Peter (2001). Peking 1900: The Boxer Rebellion. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-181-8.

- Klein, Thoralf (2008). “The Boxer War-the Boxer Uprising”. Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence.