The Brunswick Manifesto is a document written on July 25, 1792, by the Duke of Brunswick, commander of the Prussian armies. Through this text, the duke demands that the Parisian revolutionaries cease their activities and restore Louis XVI to his powers. The manifesto also threatens severe punishments for any attack on the Tuileries Palace or any harm done to the royal family. To understand better, this letter was written three years after the start of the French Revolution.

Following the flight to Varennes, the King of France lost the trust of the French people. He was forced to accept a constitutional monarchy (a monarchy where the powers of the king are limited) and lived under surveillance at the Tuileries. He lost the absolute and divine power of his ancestors. Neighboring kingdoms could not accept that revolutionaries were taking power in France and supported Louis XVI.

War was declared in April 1792. On the advice of counter-revolutionary émigrés, the Duke of Brunswick wrote his manifesto, which was published on August 3, 1792, in the French press. The text angered Parisians, who stormed the Tuileries Palace on August 10, 1792. The monarchy was ultimately abolished, and the royal family was imprisoned before their trial.

Why Was the Brunswick Manifesto Written?

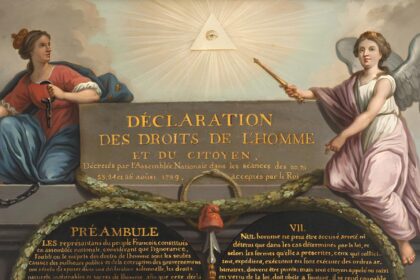

The Brunswick Manifesto was written in July 1792. What should we remember about the context of the time? The French Revolution began three years earlier with a succession of foundational events: the convocation of the Estates-General, the creation of a constituent assembly, and the storming of the Bastille, with the date of July 14, 1789, remaining symbolic. Faced with revolutionary pressure, Louis XVI was powerless. The Assembly proclaimed the end of the feudal system and privileges. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was also voted on.

In June 1791, Louis XVI felt that his power was slipping away. He refused to abdicate and decided to leave Paris to take refuge in eastern France. His escape was set for June 20 of that same year. The following evening, the king and his family were ultimately arrested at Varennes, in the Meuse.

In September 1791, a constitution limiting the powers of the king was adopted, thus establishing a constitutional monarchy. This marked the end of the absolute divine monarchy of the kings of France.

France declared war on Austria on April 20, 1792. Francis I of Austria, who was none other than Marie Antoinette’s nephew, allied with the Kingdom of Prussia to march on France. Generally, foreign kingdoms feared that the Revolution would spread beyond France. In June 1792, revolutionaries stormed the Tuileries Palace and threatened Louis XVI. They demanded that the king lift his veto on decrees concerning the deportation of refractory priests and the creation of a camp of national guards, but the sovereign refused to yield. The idea of frightening the revolutionaries then took root among royalists.

Who Is the Author of the Brunswick Manifesto?

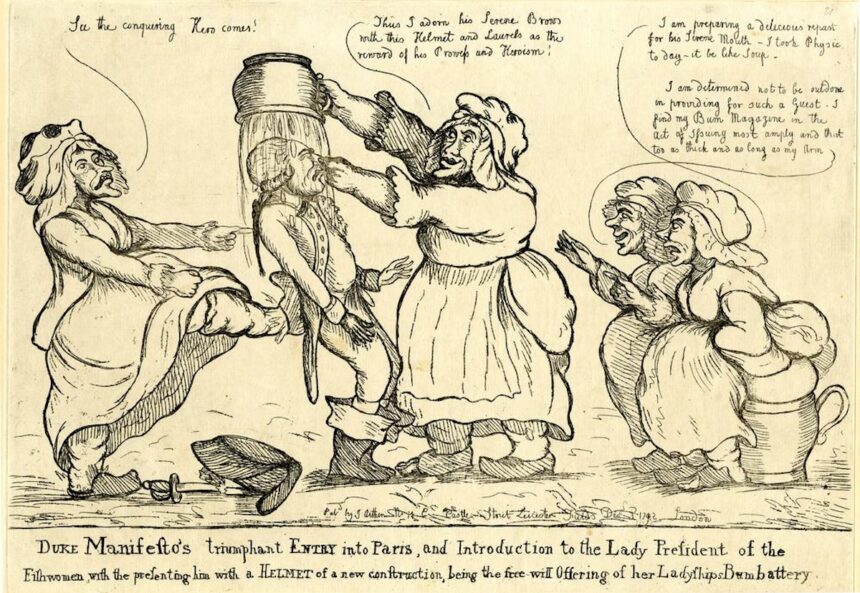

Although the manifesto has been attributed to the Duke of Brunswick-Lunebourg (Charles-William-Ferdinand), it was actually written by émigrés favorable to the king who had chosen to flee the French Revolution. Between July 14, 1789, and 1815, approximately 140,000 French people went to various emigration zones such as Lower Canada (a British colony), England, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Spain, Italy, the United States, and Russia.

It was Axel von Fersen, a Swedish count favored by Marie Antoinette, who initiated the Brunswick Manifesto.

He also participated in the flight to Varennes in 1791. In July, Axel von Fersen helped prepare a European coalition against the French Revolution and hoped for a swift victory and a return to absolute monarchy. More concretely, it was Geoffroy de Limon (a French politician) and Jean-Joachim Pellenc (a former secretary to Mirabeau) who wrote the text. Louis XVI, who knew that a manifesto was being drafted, sent Jacques Mallet du Pan to participate in it and avoid threats against the revolutionaries. However, his instructions were not followed, and the manifesto was sent on July 25, 1792. To this day, it is unknown whether the Duke of Brunswick actually signed the text that bears his name.

To Whom Is the Brunswick Manifesto Addressed?

The Brunswick Manifesto was published on August 3, 1792, in Le Moniteur universel, a French newspaper created in 1789 by Charles-Joseph Panckoucke. This media outlet was known for being a propaganda journal and the official organ of the government. The text is addressed to “the city of Paris” and “all its inhabitants without distinction.” More specifically, it targets the French population and the revolutionary forces aiming to depose Louis XVI. Here is an excerpt from the Brunswick Manifesto:

The city of Paris and all its inhabitants without distinction shall be required to submit at once and without delay to the king, to place that prince in full and complete liberty, and to assure to him, as well as to the other royal personages, the inviolability and respect which the law of nature and of nations demands of subjects toward sovereigns […]

What Threat Does the Brunswick Manifesto Pose?

The Brunswick Manifesto is unequivocal: it orders the revolutionaries to “return without delay to the path of reason, justice, order, and peace.” All inhabitants of Paris are “required to immediately and without delay submit to the king.” In addition to urging citizens to halt the revolution immediately, the text threatens the destruction of the capital and severe reprisals.

Their said Majesties declare, on their word of honor as emperor and king, that if the chateau of the Tuileries is entered by force or attacked, if the least violence be offered to their Majesties the king, queen, and royal family (…), they will inflict an ever memorable vengeance by delivering over the city of Paris to military execution and complete destruction, and the rebels guilty of the said outrages to the punishment that they merit.

It is in the second part of the manifesto that threats against the revolutionaries are found. In the first part, the writers explain why Prussia and its allies oppose the new form of governance established in France. Opponents of the Revolution are referred to as the “healthy part of the nation.” This text is a call to “end the anarchy within France.” Read the Brunswick Manifesto.

What Were the Consequences of the Brunswick Manifesto?

The publication of the Brunswick Manifesto did not have the intended effect, which was to frighten the revolutionaries into turning back to their king.

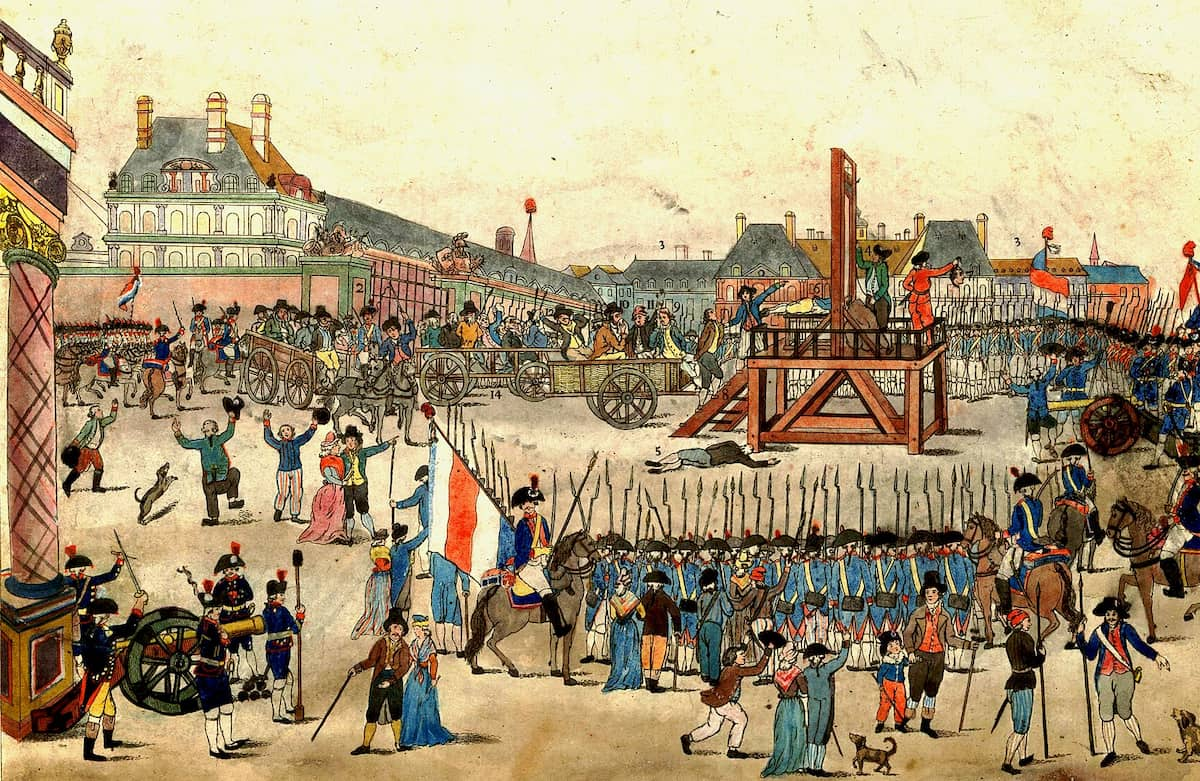

On the contrary, the Revolution immediately became more radicalized. After the manifesto’s publication on August 3, an assault took place on the Tuileries on August 10, 1792.

The revolutionaries seized the palace, which was the seat of executive power, and managed to defeat the 900 Swiss Guards. Louis XVI and the royal family sought refuge in the National Assembly, which chose to suspend the king. He and his family were transferred to the Feuillants Convent, a Parisian monastery, where they lived in deprivation for three days. On August 13, they were taken to the Temple prison.

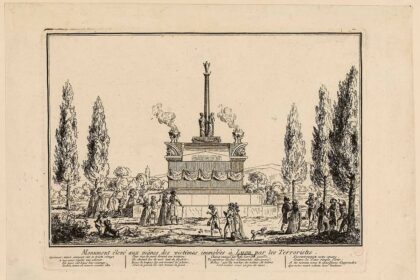

At the same time, Paris became the epicenter of intense tensions: all enemies of the Republic were hunted down, and the prisons were filled with royalists and dissenters. In early September 1792, the most radical revolutionaries massacred more than 1,300 prisoners in various prisons as an act of revenge. The “September Massacres” took place notably at the Abbaye prison, the Force prison, and the Grand Châtelet prison. These summary executions also occurred in the provinces (Orleans, Reims, Versailles…) and resulted in over 150 deaths. The atmosphere was oppressive as the Austro-Prussian invasion continued.

On September 20, violence continued with the Battle of Valmy: the Prussians, who had crossed the Argonne (a natural region in northeastern France), attempted to march on Paris. Two generals, François Christophe Kellermann and Charles François Dumouriez, managed to stop the Prussian advance in the village of Valmy. This battle was the first victory for the French army in the context of the Revolutionary Wars.

The trial of Louis XVI began on December 11, 1792, and lasted until mid-January 1793. On January 21 of the same year, the king was guillotined at the Place de la Révolution (now Place de la Concorde).