Alchemy in the Byzantine world is part of a set of scientific practices inherited from ancient civilizations, such as the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and Mesopotamians, which Byzantine intellectuals studied, taught, and transmitted through scientific institutions like the University of Constantinople.

Historical Background

For ancient civilizations, alchemy was a coloring process used to modify objects, most commonly metals, to give them a new value. The modification is achieved using dyes or chemical elements. Ancient alchemy was also a way to express the mystical nature of the world and was often combined with philosophical, religious, or astronomical studies. This perspective on ancient alchemical practice was passed down to Byzantine scholars, for whom scientific practice was more about preserving and studying the great works of antiquity than introducing new developments. For example, the writings of Greek philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, and Democritus held great importance in Byzantine scientific discourse.

Generalities of Byzantine Alchemy

Alchemy played a significant role in the work of Byzantine scientists, who often held ecclesiastical positions as well. For Byzantine intellectuals, alchemy represented a meeting point between the scientific and spiritual domains. Alchemy in the Byzantine world cannot be separated from philosophy, rhetoric, astronomy, astrology, and religious studies. Byzantine science is primarily known for sharing the scientific knowledge of ancient thinkers with other civilizations of their time, such as the Muslims or, following the fall of Constantinople, with the great thinkers of the Italian Renaissance. In this sense, Byzantine alchemists played a key role in the development of alchemy across Europe and the Middle East.

Precursors of Alchemy in the Byzantine Empire

Texts from the 4th Century

Two of the earliest precursor texts of Byzantine alchemical practice are manuscripts that belonged to the Greek merchant Giovanni Anastasi in the 18th and 19th centuries. They were respectively transmitted to the Museum of Leiden in the Netherlands and the Kungliga Biblioteket in Stockholm. These two texts, likely originating from the Egyptian scientific tradition and dating back to the 4th century, compile several recipes related to the transformation of silver, gold, gemstones, and fabrics. They align with the so-called pseudo-Democritean tradition, stemming from the materialistic ideas of the Greek philosopher Democritus.

These texts represent some of the earliest tangible examples of alchemical recipes that reached the Byzantine world and precede other foundational texts for Byzantine alchemical works, such as those of the Greco-Egyptian alchemist Zosimos of Panopolis.

Zosimos of Panopolis

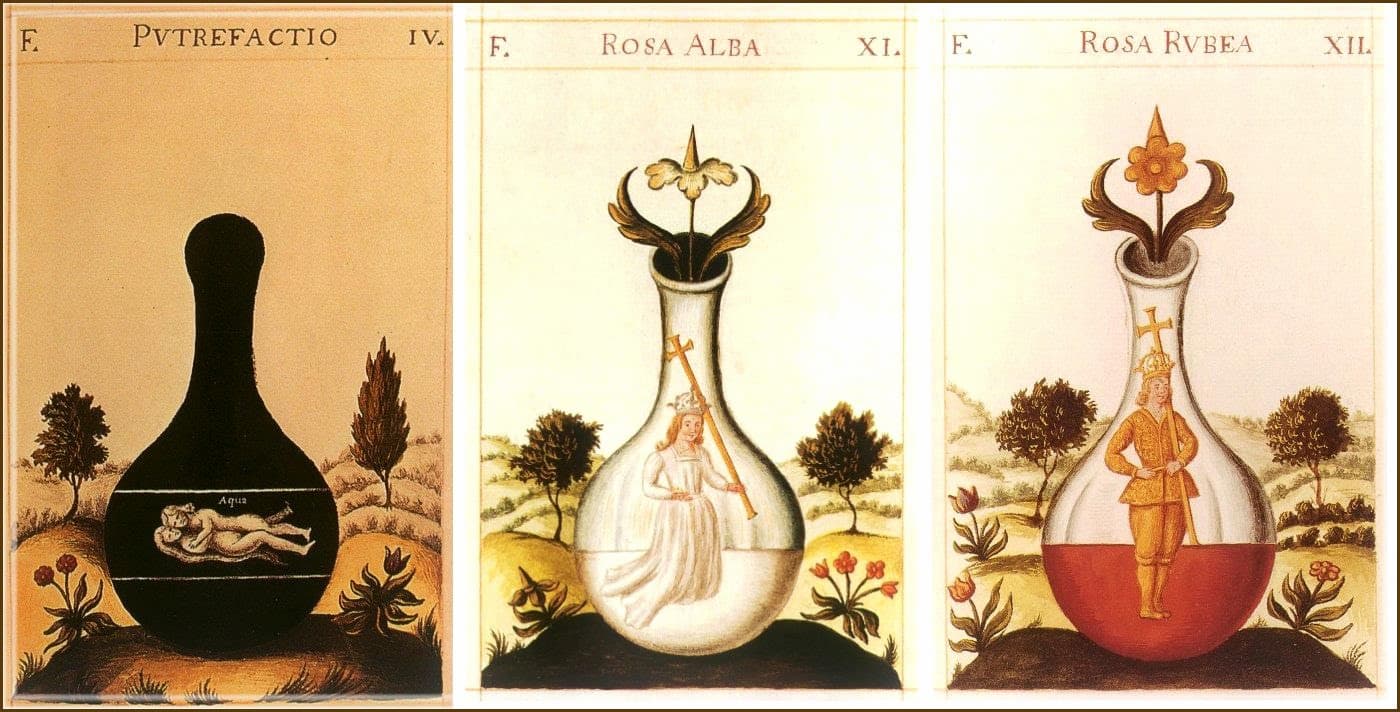

The works of Zosimos of Panopolis go even further by establishing a connection between the transmutation of metals and religious practice. Zosimos’ works also depart from simple recipes to describe much more complex chemical processes. According to Zosimos’ writings, all substances are composed of a body (soma) and a volatile part (pneuma), attributable to their spirit.

Alchemical practice, according to Zosimos, is essentially a process seeking to use fire, either through distillation or sublimation techniques, to separate the spirit from the body. This concept would have a significant influence on Byzantine and Arab philosophers in the following centuries, and Zosimos can be considered the first major philosopher in the Byzantine tradition.

Stephanus of Alexandria and the School of Alexandria

The beginning of the 7th century witnessed the emergence, in the realm of alchemy, of a circle of Alexandrian thinkers commonly referred to as the School of Alexandria, or the Philosophical Academy of Alexandria. This school encompasses several great thinkers, including Stephanus of Alexandria, an alchemist, mathematician, philosopher, and astronomer. Stephanus of Alexandria was one of the first Alexandrian thinkers to export his ideas to the Byzantine world, following an invitation to the court of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius around the year 610.

Stephanus of Alexandria and his compatriots, such as Olympiodorus the Alchemist, Synesius of Cyrene, and Aeneas of Gaza, dedicate themselves to the study of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian alchemy and philosophy. Synesius is notably credited with a commentary on the pseudo-Democritean writings dating back to 389, and Olympiodorus with a commentary on the works of Zosimos. Stephanus of Alexandria, on his part, provides several commentaries on the works of Plato and Aristotle, along with a mystical treatise on the transmutation of metals into gold. Commenting on Greek alchemical works, he asserts:

“The wise speak in riddles as much as possible… Material furnaces, glass instruments, bottles of all kinds, alembics, and kerotakis [a metal plate placed on a container with burning coals to melt the wax and condense vapors]—those who attach themselves to these vain objects succumb under this tedious burden.”

For him, alchemy was more of a mystical pursuit than a scientific one, dissociating itself from the material aspect of alchemy, which he defines as “the systematic study of the creation of the world through the word.” His works consisted of revisions of atomic concepts from the ancient era, such as the Stoic model wherein the spirit is composed of air and fire and has the ability to penetrate every element of the world and govern it.

The spiritual aspect is an integral part of Stephanus of Alexandria’s work, illustrating the strong connection between sciences like alchemy and the ecclesiastical profession in the Byzantine Empire. Indeed, religious congregations and monasteries were significant centers of Byzantine science, and the teachings at the University of Constantinople were mostly delivered by men of religion.

While Stephanus of Alexandria was not officially an ecclesiastic, several references highlight the importance of his Christian fervor in his works. King Heraclius is said to have invited Stephanus of Alexandria shortly after his ascent to power around 610, where Stephanus would have taught philosophy and alchemy for several years.

The role of Emperor Heraclius in the development of a genuine alchemical domain among Byzantine thinkers is vaguely defined, but some claim that the pursuit of the philosopher’s stone had become an obsession for him. The ability to transform metals into precious metals held great allure for the rulers and societies of the time, even though alchemists, like Stephanus of Alexandria, appeared to dissociate themselves from the material aspect of this practice.

A student of Stephanus of Alexandria, named Marianos or Morienus, is said to have introduced alchemy to the Muslim world by initiating the Umayyad Prince Khalid ibn Yazid around 675. Muslim princes were quickly drawn to the promises of this occult science and showed a keen interest in it in the following centuries.

Michael Psellos

After the death of Emperor Heraclius, the intellectual circles of Constantinople found their work contested by the Church. Consequently, Byzantine studies and writings experienced a significant decline in the centuries following the 600s.

Scientific practice was banned from the Byzantine territory for several centuries before being reinstated during the reign of Emperor Constantine VII, known as the Porphyrogennetos or Purple Born (944–959). One of the central figures in Byzantine scholarship, and the one who would bring scientific practice to the forefront, is the scientist Michael Psellos (1018–1078).

Michael Psellos is one of the most influential figures in Byzantine scientific history, credited with restoring the reputation of scientific institutions such as the University of Constantinople, which had seen a sharp decline since the end of Emperor Heraclius’ reign. At the age of 25, Psellos claimed to possess all the knowledge of the world. He quickly established himself as an exceptional speaker and became a renowned and respected professor, leading to an invitation by Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos to pursue a career in the imperial chancellery. Psellos played a crucial role in the administration of the empire.

During his reign, Emperor Constantine Monomachos advocated for the restoration of the importance of culture in Byzantine society, providing a platform for intellectuals like Psellos and their teachings. It appears that Psellos took this opportunity to legitimize the alchemical domain, notably with his writings “Epistle on Chrysopoeia” and a letter addressed to Patriarch Michael I Cerularius (Patriarch of Constantinople) titled “How to Make Gold.”

This letter posits that the transmutation of metals is a completely natural process and presents a series of recipes for transforming various metals into gold. However, according to the Belgian historian Joseph Bidez, who published Psellos’ writings in 1928, Psellos possessed inaccurate knowledge of alchemical processes. Despite this, Michael Psellos had an impact on the evolution of Byzantine culture and the restoration of alchemy as a subject of study on par with philosophy and rhetoric.

The Transmission of Alchemical Concepts to the West

Later on, alchemy became primarily the concern of the Arabs and then of great European alchemists like Nicolas Flamel, but Byzantine alchemy continued to influence its practice, notably through the writings of the Catalan scientist Arnoldus de Villa Nova, whose works are believed to have emerged in Southern Italy in the 14th century.

His translations of alchemical works from the Byzantine Empire are thought to have influenced the practices of humanist thinkers during the Renaissance. The fall of Constantinople in 1492 is also said to have led to an exodus of thinkers and priests who possessed manuscripts containing alchemical processes still unknown to the West.