Midway through the 1970s, António de Oliveira Salazar established the Estado Novo, a dictatorship. Following Salazar’s departure in 1968, his successor, Marcelo Caetano, followed an open policy while refusing to give independence to the Portuguese colonies, particularly Angola and Mozambique. The colonial conflicts engulfed Portugal, resulting in the deaths of numerous troops.

António de Spínola, deputy chief of staff of the armed forces, opposed the war, as did the young captains of the MFA (Movement of the Armed Forces). On the night of April 24 to April 25, 1974, the MFA staged a coup d’état, ending the Salazarist dictatorship. After two years, Portugal finally experienced political stability again in 1976, when democracy was restored.

The Carnation Revolution was led mainly by a group of Portuguese officers, including Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, Salgueiro Maia, and Vasco Lourenço. These officers played an important role in organizing the coup. Political figures such as Álvaro Cunhal, leader of the Portuguese Communist Party, and other civilian opposition leaders also supported the revolution.

Causes of the Carnation Revolution

After a military-led coup d’état in 1926, Portugal became a dictatorship. In 1933, a new constitution created the Estado Novo (“New State”), an authoritarian government led by António de Oliveira Salazar. Prior to that year, Portugal was ruled by the Ditadura Nacional (National Dictatorship).

Political opposition movements were not tolerated by the anti-democratic, corporatist, and Catholic dictatorships. The Council of Ministers served as the ultimate authority. Strikes were outlawed and labor unions were controlled by the government. The International and State Defense Police, the regime’s police force, monitored and suppressed political opponents. The Estado Novo was founded on the same colonial principles. Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau were all colonies of Portugal.

In 1961, the Portuguese military was sent into the colonies to quell independence aspirations. Salazar had a stroke in 1968. He was replaced as president by Marcelo Caetano. Meanwhile, the Portuguese army lost numerous men to the ongoing colonial battles. Soldiers like António de Spnola urged the government to engage with independence fighters because they believed they had lost the battle in the colonies. Portuguese officers organized the decolonization-supporting MFA (Movement of the Armed Forces) in 1973. The MFA orchestrated the coup known as the “Carnation Revolution” on April 25, 1974.

Salazar’s Dictatorship

The authoritarian system headed by António de Oliveira Salazar, President of the Council of Ministers since 1932, is often referred to as the Salazarist dictatorship. Estado Novo (literally “New State”) was a dictatorship that took power in 1933. Anti-communism, anti-socialism, anti-syndicalism, anti-liberalism—these were the tenets upon which it was founded. But it maintained some distance from fascism. The affluent landowners, bankers, and manufacturers of Estado Novo backed a corporatist, anti-democratic administration. “God, Fatherland, and Family” was the organization’s official motto.

There was just one legal political party, the National Union, which emerged in 1930. Trade unions and independent publications were also banned, along with the Portuguese Communist Party. The police of the dictatorship, who also engaged in censorship, detained dissidents. Salazar was a Catholic who signed a document expanding the Church’s authority in 1940 called the Concordat. The Salazarist regime also advocated a return to colonial ways of thinking.

Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau were all Portuguese colonies that the country fought hard to maintain in the 1960s. Salazar had a stroke in 1968. Marcelo Caetano, the leader of Estado Novo, succeeded him in office. In an effort to liberalize the nation, Caetano enacted a number of changes. He ignored mounting pressure from the military to end the conflict in the colonies, though.

Leading Figures of the Carnation Revolution

Officers from the Portuguese army were behind the Carnation Revolution. As early as 1961, Portuguese armed forces intervened in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau to suppress independence movements. The Salazarist dictatorship wanted to maintain power in these “overseas provinces”. Faced with resistance from the independence movement, Portugal was forced to send more and more troops. By the early 1970s, casualties were high, and Portuguese troop morale was at an all-time low. Officers, including António de Spínola, the governor and commander of the armed forces in Guinea, tried to prove to the President of the Council, Marcelo Caetano, that the war was lost.

Caetano refused to negotiate with the independenceists. In 1973, a group of officers formed the MFA (Mouvement des Forces Armées—Movement of the Armed Forces) and initially strongly opposed a decree granting militias access to professional officer status. Composed mostly of young army captains, the MFA organized and called for an end to the war in the colonies.

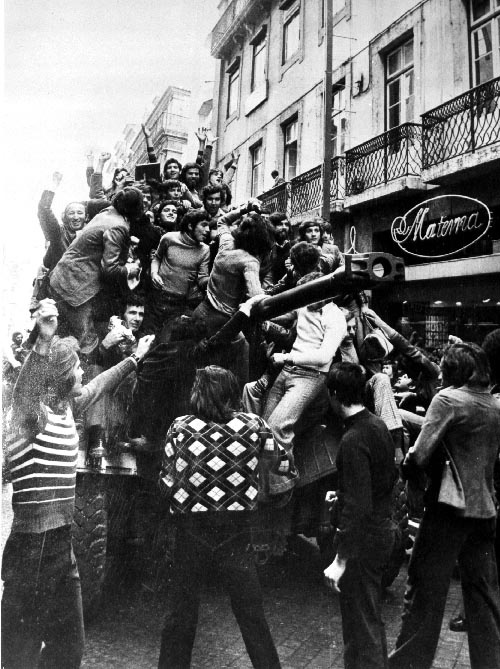

In February 1974, António de Spínola’s book “Portugal and the Future” was published along these lines. On April 25, 1974, the MFA organized a coup d’état. And where were the carnations in all this? On that day, the army, supported by part of the population, gathered in Lisbon’s flower market. They were presented with red carnations by local shopkeepers and placed the flowers in the barrels of their rifles. It was this gesture that gave the events the name “Carnation Revolution”.

The Carnation Revolution is celebrated every year on April 25 as a national holiday in Portugal, known as “Dia da Liberdade” (Freedom Day). It is commemorated with various events, parades, and ceremonies throughout the country. The red carnation remains a symbol of the peaceful nature of the revolution and its role in bringing democracy to Portugal.

April 1974 Coup d’état in its Phases

MFA soldiers launched the coup on the night of April 24, 1974. The song Grândola, Vila Morena, forbidden by the regime, was broadcast on the radio after midnight on April 25. The uprising soldiers prepared to take control of the country’s vital points.

- At 3 a.m., they took control of the Lisbon airport, the radio station, then the military headquarters and the Porto airport.

- At 4.26 a.m., the MFA issued its first communiqué over the radio, calling on the police to stay in their barracks and asking the population to stay in their homes. Other communiqués issued in the following hours warned various military and police forces that any act of resistance against the MFA would be violently suppressed.

- At 5.30 a.m., Captain Salgueiro Maia laid siege to Lisbon’s famous square, Terreiro do Paço. He surrounded the main barracks of the city gendarmerie, where the President of the Council, Marcelo Caetano, had taken refuge.

- It is 16:00 when he surrenders on the condition that António de Spínola regains power. The MFA agrees.

- At 5.45pm, Spínola arrives.

- Then, at 7.30, Caetano Pontinha is taken to the command center.

- At 8 o’clock, PIDE (Estado Novo’s secret police) opens fire on the crowd, killing four people. This was the only act of resistance to the revolution. After Spínola’s intervention, PIDE agreed to surrender.

- At 1:30 a.m. on April 26, the members of the Junta de Salvação Nacional (National Salvation Junta) were introduced on television. This group of officers, headed by Spínola, was given the task of temporarily governing Portugal.

Consequences of the Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution overthrew the Salazarist dictatorship. Portugal entered a period known as the “Ongoing Revolutionary Process (Processo Revolucionário Em Curso)”. For two years, the country was ruled by the Junta de Salvação Nacional. While Marcelo Caetano was exiled to Brazil, political prisoners were released, and dissidents returned to the country. However, the left-leaning MFA disagreed with António de Spínola, who advocated a return to the old institutions.

After the failure of the first provisional government in May 1974, the MFA wanted to limit Spínola’s actions. Spínola resigned and took part in the failed coup d’état on March 11, 1975. Meanwhile, the former Portuguese colonies gained their independence and the colonists were repatriated to Portugal. The MFA, supported by the far left, nationalized banks, insurance companies, and other sectors such as the steel industry. But it faced off against moderates who seized power at the end of 1975. Portugal adopted a new constitution on April 2, 1976, and became a democracy.