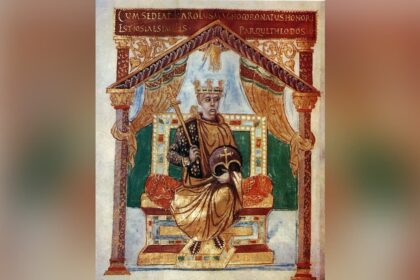

Charlemagne, also known as Charles the Great, founded the Carolingian dynasty and lived from 742 to 814. He was a king of the Franks and eventually an emperor of the Western Roman Empire. After the death of his brother Carloman in 771, this oldest son of Pepin the Short ruled over an empire that included all of Gaul and a portion of Germania. When he declared himself king of the Lombards in 774, he embarked on a program of expansion and led multiple military expeditions. During his 46 years at the helm, the Frankish kingdom expanded to become the biggest in Europe since the collapse of the Roman Empire. Charlemagne was anointed Emperor of the West on Christmas Day, 800, with the support of the church since he had forced Christianity onto the subjugated peoples. The author of The Life of Charlemagne, Eginhard, gave him the nickname “the emperor with the flowery beard” after describing him in detail around the year 830.

- Charles’s early years

- Charlemagne’s wives

- Charles the Great: A well-surrounded monarch

- Emperor Charlemagne: A man of war

- Who crowned Charlemagne?

- A cultural propagator

- Charlemagne: Father of Europe

- Life of Charlemagne: The oldest biography of the emperor and his reign

- Joyeuse: The sword of Charlemagne

- THE KEY DATES OF CHARLEMAGNE

Charles’s early years

There was some debate regarding when exactly Charlemagne was born. According to Eginhard, an abbot and scholar from the ninth century, the date was April 2, 742. Not once was a birthplace specified. A number of scholars argue that Austrasia, in what was then the northeastern part of France, was the site of his birth. Charles would have been born illegitimately as the son of Pepin the Short and Berthe the Great. More than a year after he was born, in 743 or 744, his parents tied the knot in a religious ceremony. It’s all fuel for the debate among historians over when and where he was born.

In 754, when the Pope Stephen III was visiting his father, he was baptized. When Charles was a kid, he never took the time to learn to write. His maturity as an adult would make up for his immaturity as a child. But he could read, and he even knew a little Latin. However, materials that reflect his boyhood and childhood are so few, if not nonexistent, that it is impossible to paint a clear picture of young Charles. However, he was particularly close to his younger, more ostentatious sister, Ghisla. Most of what happened in their youth is a mystery.

Charlemagne’s wives

Six of Charlemagne’s spouses were recognized by the church. Casually, he was having many affairs at once. Physically, he was described by his biographer Eginhard as follows: “He stood at a lofty 6’3″ (1.90 m) tall, and his frame was both wide and sturdy. His face was round, and his eyes were big and bright. His nose was a bit larger than typical. His hair was gorgeously white. His overweight body, short neck, and bulging stomach were hardly noticeable. In terms of appearance, he was confident and macho. The voice was distinct, but a little too high-pitched for his frame.” Given that the average male of the time stood 1.67 m tall, the man appeared to have an advantageous body and exceptional size.

He tied the knot for the first time in 768. He wed Himiltrude, the duke’s daughter in Burgundy. He stayed with her for two years and had two children with her before leaving her for Desiderata, the daughter of Desiderius, king of the Lombards. This political marriage ended rapidly due to sterility issues. Charlemagne, being about 30 years old, wed a 13-year-old named Hildegard. She had nine children until she miscarried and died in 783.

Charlemagne found solace in his marriage to Fastrada, which resulted in the birth of their two daughters two months later. In 794, she passed away, and her successor was Liutgard, the daughter of the Count of Alsace. After her passing in 800, our Carolingian Dom Juan began a concubinage with Gersuinda, the Saxon king’s daughter. She gave birth to his daughter when he was sixty-six. Charlemagne had multiple relationships outside of his formal marriages, including one with his sister Ghisla in around 771. To top it all off, she conceived a child. Fearing public disgrace, Charlemagne swiftly found her a husband, Roland, and also passed a capitulary outlawing incest. Overall, Charlemagne was blessed with seventeen offspring.

The sum of these marriages was not meaningless. In other words, Charlemagne did not choose his wives at random. These were, first and foremost, political moves designed to earn the support of his adversaries. This was what he admitted: “I alone have the duty and the right to take a wife. In a family like ours, marriage should only serve to conclude alliances, pay debts, or ensure an heir to the throne.”

Charles the Great: A well-surrounded monarch

Insight on Charles’s private life may be gleaned from the available materials. The only companions we really know about were his brothers in arms, with whom he went on campaign. Roland (736-778), also known as the Roland the Valiant, was one of his most well-known comrades. Roland, a Frankish warrior and the namesake of the immortal ballad, was the nephew of Charlemagne. Count of the march of Brittany, he was also very close to his uncle.

During the Battle of Roncesvalles (778), where he died, when Charles’ army was retiring, Roland and his troops were ambushed between two cliffs. After that, Roland drew his sword, Durandal, and engaged in combat. After finding himself quickly outnumbered, he blows his breath to summon his buddy Charles for assistance. It was too late by the time the latter showed up. When he saw his nephew’s body, he hugged it tightly and said, “There will never be a day when I will not suffer thinking of you.”

Charles installed in all the empire of the “counts,” descended from the aristocracy or confirmed warriors, to help him manage his vast domain from the palace of Aix la Chapelle. They presided over homogeneous regions and were responsible for administering the territory in the name of the sovereign. Because of the great distances involved, the counts soon began to take liberties that were inappropriate. Charles used “missi dominici” to assert his dominance over the situation. A priest and a layman, these “messengers of the master” ceaselessly crisscrossed the kingdom to spread the word about royal decrees and see to it that they were carried out as intended. Rather of achieving its original goal, the system would swiftly evolve into the foundation of the feudal order.

There were a lot of smart people hanging around at the Carolingian king’s court. The emperor relied heavily on the counsel of Alcuin of York. He oversaw the Palatine Academy, the premier educational institution in the Roman Empire. His contemporaries considered him “the most knowledgeable man of his day,” as proclaimed by Eginhard. The Irish monk Dungal of Bobbio served as Charlemagne’s official astronomer. He laid the groundwork for ideas that Nicolaus Copernicus would refine 700 years later. Eginhard, Theodulf, and Raban Maur weren’t the only scholars vying for a place at court; the Carolingian Empire was a hive of intellectual activity.

Bertrada of Laon, Charles’ mother, was very important to him. She even meddled in her son’s political career. Some have speculated that Bertrada would have urged Charles to marry Desiderata, the daughter of the Lombard monarch, in order to cement an alliance. For the record, the day Carles branded his mother a “whore” was the day their tight bond deteriorated. This person would have snapped back, “My son, do not evoke my infidelities, that could return to you in full face.”

Emperor Charlemagne: A man of war

When Charlemagne’s father, Pepin the Short, died in 768, he left his kingdom to his two sons, Charles and Carloman, effectively beginning Charlemagne’s “political” career. As a result of their animosity, the two brothers ended up fighting over who would rule. With Carloman’s death in 771, Charles was left as the sole ruler of the Frankish kingdom.

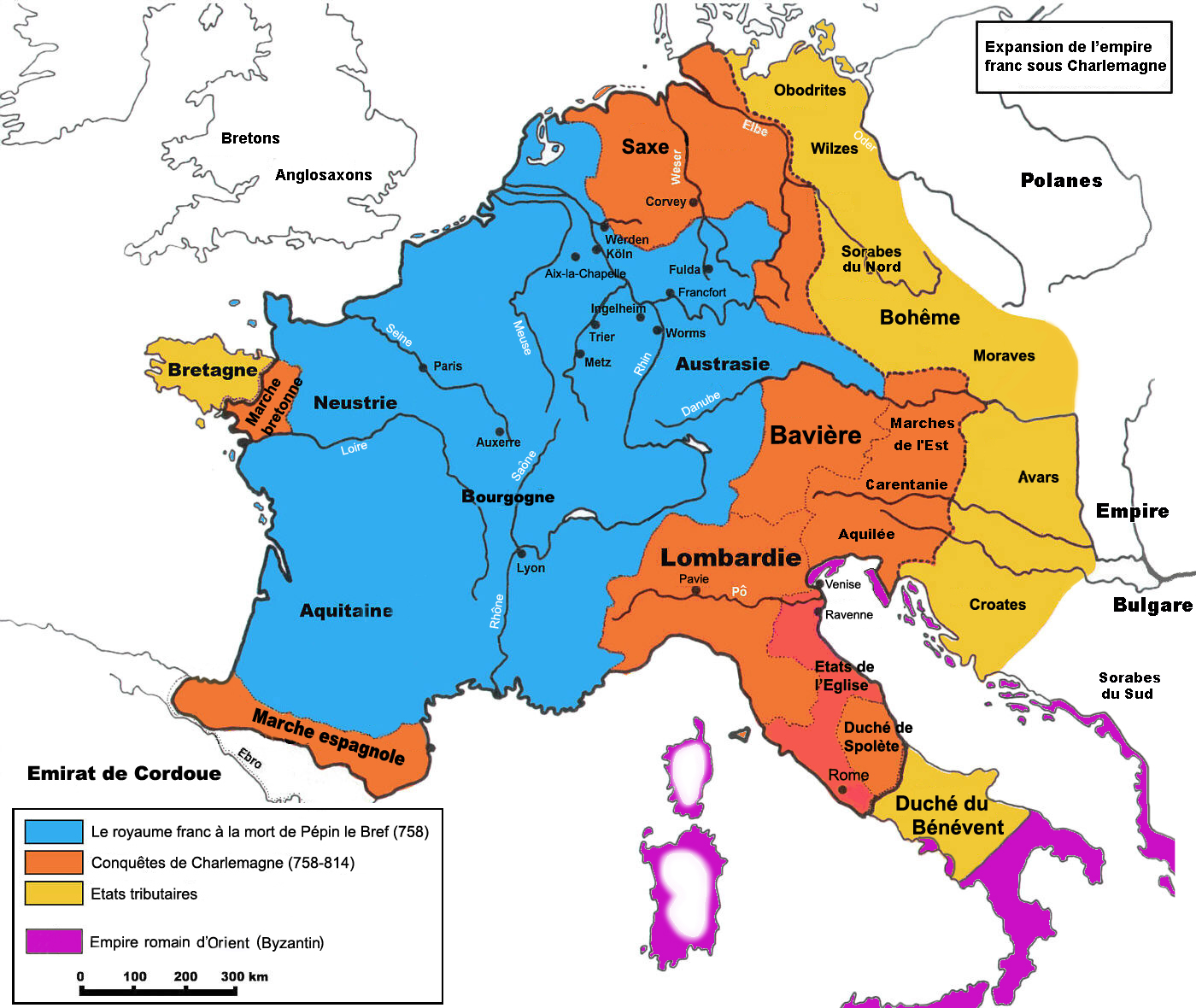

By the middle of the eighth century, after the fall of the Roman Empire and the invasions of barbarian tribes, the Frankish kingdom was the only stable and viable state in Europe. The Muslims had destroyed Visigothic Spain, the Lombards and the Byzantines had split up Italy, and central and northern Europe were split up into a plethora of barbarian kingdoms and nations with unclear borders. Charles’s kingdom was formidable, but it faced formidable enemies on all sides.

Frankish society was hierarchical and clientelist, with strong traces of feudalism already present. The landowner lords became emotionally attached to their vassal free men by providing them with shelter, food, and numerous costly gifts in exchange for their armed service.

In spite of this, the economy at the time was not in a particularly promising position. The industry sector fled the cities and settled in the countryside, clustering around farms established in Roman-style villas and operating in a state of semi-autonomy. Since the Roman peace no longer guarantees the security of commercial exchanges, currency has been scarce. Since land was the only commodity available, appropriating neighboring plots was a necessary evil for sustaining the system.

Why was Charlemagne a great conqueror?

Charles began his campaigns against the Saxons as early as 772; by 804, after much struggle, he had ultimately won. In 785, he issued the Saxon capitulary, which mandated baptism for all Saxons and made the practice of pagan rituals a capital offense. The Lombard throne had been vacant since Desiderius’s deposition in 774, when he conquered Pavia and assumed the kingship. His conquest of the area that is now known as the Spanish March (present-day Catalonia) occurred between 785 and 801. After a successful journey over the Pyrenees, Charles’ rearguard was caught in an ambush laid by the Basques as they returned to Roncesvalles.

Charles’s strength was his able army and his brutal, even barbaric, approach to battle. In this kingdom, serving in the army was obligatory for all adult males. Despite this, the total number of forces was still manageable, with 36,000 light cavalry, 5,000 heavy cavalry, and numerous infantrymen. The victory was due to the army’s superior training; its armored cavalry quickly overpowered the opposition. Each campaign was a resounding success because of the lightning-quick maneuvers and the pincer technique.

Charlemagne’s united realm extended from Saxony in the north to Navarre or Rome in the south, and from Aquitaine in the west to Carinthia (Austria) in the east. A few historians credit him with creating a “new Rome.” That Charlemagne wanted to restore the Roman Empire is shown by the fact that he had the phrase “renovatio Romanorum imperii” written on multiple seals soon after becoming king.

And a man of faith

As emperor, Charlemagne made it his mission to spread Christianity. The conversion to Catholicism that followed all of his victories was usually coerced. The fact that the people of the empire were united in their religion was the empire’s true bedrock. In this hypothetical “State,” Emperor Charlemagne’s job is to save his people. As a means of doing this, Charles often stepped in when it came to defining orthodoxy. In 794, he spoke out against a heresy sweeping across Spain at the Council of Frankfurt, a gathering of church leaders for discussion and debate. His fierce opposition to the 787 Council of Nicaea prompted him to commission the disputed Libri Carolini from the churchman and scholar of the Carolingian age, Theodulf.

After Charlemagne conquered a region, he granted capitularies to the conquered populace that encouraged conversion. The “famous” Saxon capitulary of 785 mandated mandatory baptism for all Saxons and made it a capital offense to practice any of the previous pagan rituals. This document, which enforces Emperor Charlemagne’s legislation, is modeled after the ancient code of Hammurabi and is stated as follows: “Those who force their way into a house of worship shall face the ultimate penalty. For the murder of a bishop (…), the penalty is automatic execution. Any unbaptized Saxon who hides among his people today and refuses to be baptized because he wants to keep practicing his pagan religion shall be executed (…).”

Who crowned Charlemagne?

In 800, when Charlemagne was crowned Western Roman Emperor, he was installed as ruler on a foundation of religious philosophy. As his empire grew, so did the reach of the Church. Charlemagne’s life’s work was to unite the peoples of Western Europe under a unified empire, which he saw as an extension of the Church. So it was on December 25, 800, in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome that he graciously permitted Pope Leo III to crown him Emperor of the Romans.

A cultural propagator

Charles, now firmly established in his new capital of Aachen, which benefited from being centrally located in his empire and having game forests, attracted and sometimes appointed a number of intellectuals, artists, and scholars, including many Italians, the poet and historian Paul Deacon, the grammarian Peter of Pisa, and the Englishman Alcuin, the most learned of his time, to lead the schools in the capital. He pushed for the spread of Latin, which resulted in an influx of copyists and illustrators into the monasteries. Known as the “Carolingian Renaissance,” this period of cultural and religious flourishing was crucial to the establishment of a Christian and Romanesque Europe.

Just what was it that made Charlemagne so significant? Regarding this matter, many people would name the holy Charlemagne as the one who first established a school. While evidence of schools may be traced as far back as 3000 BC in Egypt, the Carolingian monarch was the first to legislate on the construction of a school system. Admonitio Generalis (also known as the “Great Exhortation”) was composed in 789 and is the most important document.

There was a strong recommendation in the text for the clergy to get higher education so that they may better educate the populace in the Christian religion. As it spread the seven liberal arts, the Admonitio spawned a number of schools whose teachings would become the bedrock of the Middle Ages’ educational system and university culture. One early goal was to revive Latin so that sacred scriptures might be translated into other languages.

Charlemagne’s approach made it considerably simpler for Christians to promote their beliefs. The arts flourished under the Carolingian emperor, and the resurgence of Greco-Latin culture and cultural interchange among Europe’s literati took place, particularly at the royal court. The term “Carolingian Renaissance” was often used to describe this time of artistic rebirth.

Charlemagne: Father of Europe

In reality, the Empire consisted of a wide variety of peoples that spoke a wide variety of languages and followed a wide variety of laws and traditions, with the only thing they usually had in common being that they were all subject to the Emperor. In fact, at the time, his participants were rarely conscious of the fact that they shared a common identity. Their designation and identification as Europeans, in contrast to the “infidel” Muslims of the south and the Slavic pagans of the east, started to take hold, however.

Attracting many Italians, including the poet and historian Paul Deacon, the grammarian Peter of Pisa, and the Englishman Alcuin, the most learned of his time, to whom he entrusts the schools in his new capital, Aachen, which had the advantage of occupying a central position in his Empire and having the advantage of the game forests, Charles attracts around him many intellectuals, artists, and scholars, sometimes placing them in key positions. His advocacy for the spread of Latin resulted in a proliferation of copyists and illustrators in monasteries throughout the region. This explosion of culture and faith, known as the “Carolingian Renaissance,” was crucial to the establishment of a Christian and Romanesque Europe.

Was there a major political plan on the side of the man known as “Pater Europae,” the father of Europe, and “Europa vel regnum Caroli,” Europe or the kingdom of Charles, a very individualistic assessment of his accomplishments? Charlemagne seems to care more about his own legacy than the longevity of his work. After his death, the Empire was divided among his sons and grandchildren in accordance with ancient barbaric Frankish tradition, and it promptly disintegrated into a plethora of independent entities that would engage in bloody conflict with one another for the next 900 years.

The romantic image of a united Christian Europe under Charlemagne is a relatively recent creation, popularized in the 19th century especially by Victor Hugo, and it bears little resemblance to historical fact. Despite its brief existence, the Carolingian Empire served as a crucial link between classical antiquity and the rise of medieval Europe, planting the seeds of a political, cultural, and religious legacy to which the vast majority of modern Europeans can lay claim.

It was obvious that Charlemagne did not stop spreading Christianity over Western Europe at any point throughout his exceptionally lengthy reign. Even though he was regarded by some as the “Father of Europe” today, it is likely that he never saw himself in that light. Both politically and spiritually, he was preoccupied with two primary goals: the restoration of the Roman Empire and the propagation of Christianity. Charles left his own indelible stamp on history by prioritizing his kingdom. He passed away on January 28, 814, and his son and successor, Louis the Pious, was unable to stop the disintegration of the Carolingian Empire.

Life of Charlemagne: The oldest biography of the emperor and his reign

Who was Charlemagne?

The Vita Karoli Magni, by the Frankish historian Eginhard, was written in Latin between 830 and 836. It was heavily influenced by Suetonius’ “About the Life of the Caesars“, especially the section on Augustus’ life. Eginhard’s story, following the format of the Latin work, starts with the Carolingians’ ascension to the position of mayor of the palace before moving on to the reign of Charlemagne himself.

The victories of the Carolingians were extensively described, as was Roland’s death in the famous battle of Roncesvalles. Specific details about Charlemagne’s reign may be gleaned through accounts of his empire’s internal governance and the diplomatic contacts he established with neighboring kings. During the final twenty years of Charlemagne’s reign, Eginhard worked as the emperor’s personal attendant and was able to get near enough to him to paint a picture. Charlemagne was a “broad and strong” guy who was also very religious, supportive of the arts and literature, and intellectually curious enough to study Latin.

Eginhard’s goal, at a time of succession conflicts, was to highlight Charlemagne’s imperial rule. This eulogy lavishes praise on the monarch, calling Charlemagne “a good ruler,” “intelligent,” “courageous,” and “a superb strategist.” It is clear that Eginhard’s contemporaries saw significant value in the Vita Caroli Magni, as seen by the large number of manuscripts that have survived to the present day. It was at Cologne, in 1521, that the first edition of the Life of Charlemagne was printed.

Joyeuse: The sword of Charlemagne

There was no proof that Charlemagne had this sword. According to the chansons de geste, Charlemagne had a sword named “Joyeuse”, although it seems that he really had many. This crown, which had been housed in the Abbey of Saint-Denis’ treasury (Treasury of Saint-Denis) and impeccably behaved throughout the years, was worn during the crowning of French monarchs up until 1825. This item, currently housed in the Louvre, may have been used to crown Napoleon Bonaparte as emperor as well.

THE KEY DATES OF CHARLEMAGNE

September 25, 768: Death of Pepin the Short

The first monarch of the Carolingian dynasty, Pepin the Short, known as “Younger” was buried at Saint-Denis. The kingship he inherited through his father Charles Martel and marriage to Bertrada of Laon was eventually passed on to their sons, Carloman and Charlemagne. The dispute between the two brothers centered on how to divide the property. Charlemagne inherited a kingdom (Austrasia, Neustria, and maritime Aquitaine) that encircled the territories of his younger brother (Alemania, Alsace, Burgundy, Septimania, and another part of Aquitaine). When Carloman died abruptly on December 4, 771, Charlemagne seized the possessions of his older brother and dispossessed his nephews. He rose to the position of Western Emperor.

December 4, 771: Charlemagne gains authority

Carloman, King of France, passed away at Samoussy. The death of his brother Charles I gave him the opportunity to grab the estate he had planned to leave to his sons. With the support of Archbishop Wilcharius of Sens, he became the only ruler of the Franks and was later crowned “Emperor of the Romans” by Pope Leo III in St. Peter’s Basilica on December 25, 800, changing his name to Charlemagne.

774: Charlemagne confirms the Papal States

Charlemagne, the son of Pepin the Short, maintained the temporal power of the pope over the Papal States established in 756. Thereafter, the Papal States would progressively grow at the pace of contributions and conquests.

August 15, 778: Death of Roland at the Pass of Roncesvalles

Roland, an ally of Charlemagne, perished during a surprise assault by the Vascons (Basques), at the pass of Roncesvalles (Pyrenees). He was returning from Spain with his troops, having fought the Arabs there. His heroic deeds, as described in “La chanson de Roland,” would make him an inspiration to readers.

781 : Alcuin assumes control of Charlemagne’s academy

In a desire to impart education to the men in his administration, Charlemagne built the Palace School. He put his faith in Alcuin, the famous British scholar, to lead the group. A number of secondary schools with an ecclesiastical foundation were later established. This was the beginning of a great cultural renaissance in the Carolingian Empire.

Charlemagne annexes Dalmatia

Defeating the Avars, a nomadic force from Asia, was crucial for Croatia’s survival on the frontier between the Eastern Empire and the eventual Western Empire. After pushing them back and leaving it to Charlemagne to subjugate them, the Croats were now caught in the middle of a power struggle between the Carolingians and the Byzantines. As a result, the Croatian territories would be split apart. The largest area of the new Western Empire, Dalmatia, was ruled by the Franks.

December 25, 800: Coronation of Charlemagne

In St. Peter’s Basilica, the Pope, Leo III, crowned Charlemagne “Emperor of the Romans” in the Byzantine rite. By the time he was 58 years old, the king of the Franks and the Lombards had amassed an empire that stretched from the Atlantic to the Carpathians and from the North Sea to Italy.

January 28, 814: Death of Charlemagne

During his 72nd year, the Western Emperor Charlemagne passed away in the city of Aachen. Louis, the Pious, his son, became Emperor after him.

Bibliography:

- Lewers Langston, Aileen; Buck, J. Orton Jr., eds. (1974). Pedigrees of Some of the Emperor Charlemagne’s Descendants. Baltimore: Genealogical Pub. Co.

- Sypeck, Jeff (2006). Becoming Charlemagne: Europe, Baghdad, and The Empires of A.D. 800. New York: Ecco/HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-079706-5.

- Tierney, Brian (1964). The Crisis of Church and State 1050–1300. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6701-2.

- Riché, Pierre (1993). The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1342-3.

- Fried, Johannes (2016). Charlemagne. trans. Peter Lewis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674737396.

- Ganshof, F. L. (1971). The Carolingians and the Frankish Monarchy: Studies in Carolingian History. trans. Janet Sondheimer. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-0635-5.