Childhood seems to be absent from representations of the Middle Ages. And yet. Medieval iconography is rich in teachings. It is almost enough to open a medieval manuscript in any region, to carefully look at a fresco, or to contemplate sculptures to realize that the child is everywhere. As a simple spectator, one also finds the child at the center of many compositions. The authors of the medieval period were aware of this.

Children in the Middle Ages

The child thus finds his place in the numerous divisions concerning the “ages of life.” Through the writings of Philip de Novara (Les Quatre Ages de l’homme, 1260) or Giles of Rome (De Regimine principum, 1280), we can distinguish a few major stages that are found in iconography, namely: early childhood, itself divided between nfantia and dentum plantatura; once this stage is passed, one enters childhood (7–14 years), then adolescence.

Beyond the correspondence between real ages and those defined by treaties, what has held our attention here concerns the different stages of life that children face. Indeed, for the medieval period, it seems more coherent to apprehend the images based on the message they want to convey rather than trying at all costs to assign an age to a particular character. In other words, one scene shows the act of learning to walk, another the act of playing, or even the apprenticeship of a trade.

Beyond these different scenes, which constitute many stages and sometimes rites of passage, we have also tried to show that the child evolves according to his environment. Indeed, there are multiple ways “to be a child in the Middle Ages.” It is this diversity that we have tried to highlight. Similarly, medieval images help reconstruct part of the material and social environment of the child, as we will see. Finally, through the three “extraordinary childhoods,” it seems obvious that the child, as such, has his rightful place in the culture, both Christian and secular, of the Middle Ages.

In the end, it is childhood, sometimes joyous, sometimes macabre, in the countryside or at the castle, playing with a spinning top or behind the master’s workbench, that we have tried to transcribe here. Through iconography, it is possible to distinguish the different stages that make up children’s lives. Based on scholarly observations while conveying stereotypes, these images are numerous and shed light on the practices and realities of the child’s condition. Thus, being born, learning, and dying are part of the realities of the time.

To Be Born

During the Middle Ages, the worst thing for a woman was to be sterile. Within the context of the Virgin, her role was to give as many children as possible, seen as gifts from God. In the procreation system, men still played a role, as treaties encouraged them to drink thistle juice to produce male offspring. The mother was supposed to have a “more beautiful color and lighter movement” if she bore a son.

To ensure good childbirth, one could solicit the Virgin by offering her a candle, preferably on Candlemas Day. Once consumed in the church, it could be brought home and kept close. Indeed, since the 13th century, Marian worship has gained particular importance in the West. She is then associated with both purity and fertility. As the embodiment of motherhood, she is the natural protector of all mothers.

Medical treatises also concern themselves with pregnant women. Some illuminators do not hesitate to depict uteruses in which the fetus is shown in awkward positions. Interestingly, the earliest illuminations depict “asexual” fetuses. Later additions sometimes include male genitalia. A good child is, above all, a male!

Childbirth generally takes place in the presence of midwives, who assist in delivering the newborn. The father is generally absent from the scene, sometimes even excluded from the house. As soon as the baby is born, it must cry, a sign of life. Afterward, it is rubbed with rose petals and salt, and reflexes are checked. Then, a warm water bath can begin. In any case, illuminations clearly show that the infant was eagerly awaited and received with the utmost care.

Learning

After birth, the child is baptized as soon as possible, sometimes within the home itself. However, religious baptism remains mandatory and takes place shortly after childbirth, in the presence of the godfather and godmother.

This first major rite marks the integration of the newborn into the Christian community, signaling the beginning of their learning journey.

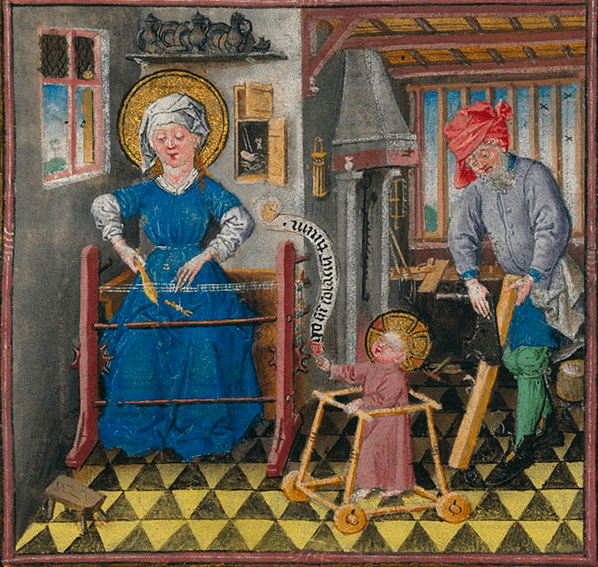

One of the first significant milestones in their lives is learning to walk. Iconography often portrays the child on all fours, although rarely, as it’s considered too reminiscent of the animal condition. The transition to standing is marked by the use of a walker or “youpala,” which can take various forms. The presence of wheels signifies mobility, albeit not without risks. Typically, speech development follows shortly after.

Another crucial moment is that of “schooling.” Illuminations reflect the reality of various educational practices. From the age of seven, children are entrusted to third parties for education, known as “fosterage” in aristocratic circles. Oblation, authorized until the 15th century, involved entrusting children to monasteries for religious education. Urban schools began to develop during the reign of Charlemagne.

Teachers provide lessons to their students. The medieval notion that school is a ladder to knowledge finds expression in iconography. Upon entering the “petite école,” children learn to read with alphabet tablets. As they progress, they ascend from floor to floor under the guidance of great masters like Peter Lombard. Childhood is indeed the age of learning, vividly represented in iconography.

Illness and Death

Infant mortality rates were very high throughout the Middle Ages. In the late Middle Ages, it was estimated that nearly one out of three children died before reaching the age of five. Death lurks at every moment. Faced with illnesses, parents can abandon everything to go on pilgrimage in hopes of a cure.

Numerous images and stories depict these miracles. For example, there is the case of a six-year-old girl who had been disabled since the age of four but regained her faculties by visiting the tomb of Saint Louis.

Beyond illness or infirmities, there are numerous other causes of death. Foremost among them is the fear of domestic accidents. Fires, for instance, both in cities and in the countryside, cause heavy damage. Wild animals are also feared. Unfortunately, caring mothers or medical remedies are not always sufficient. Iconography also attests to this.

Nevertheless, in the face of death, the reactions of parents, especially mothers, demonstrate how much childhood was valued. Everything was done to protect it.

The Child and His Environment

The child of the city is not the same as the one from the countryside, nor even that of the castle. In each place, there are different ways of representing him. At once actor and spectator, on horseback or perched in a tree, iconography does not fail to clearly distinguish social categories according to defined places. The young peasant is in the fields while the apprentice is busy in the workshop, even as the young noble learns to master his mount.

In the Country

Surprisingly, children from the peasant world are more present in miniatures than in literary texts. In this society, primarily rural—let’s not forget!—the wealth of the peasant lies in his children. Therefore, they must be taken care of closely so that they can quickly assist with agricultural work. For example, boys participate in plowing around the age of ten.

From this countryside youth, we have a witness from the 13th century in the person of the Franciscan Thomas Docking of Oxford. Thus, according to him, the country child “runs sometimes in the fields, sometimes in the garden, sometimes in the orchard, sometimes in the vineyard. He has his favorite moments in the year: in spring, he follows the plowmen and the sowers; in summer and autumn, he accompanies those who pick the grapes.

He enjoys picking unripe grapes; finding birds’ nests; bringing home sheep and poultry while jumping joyfully.” Iconography delights in depicting these children bustling happily with minor agricultural tasks and playing between two physical activities.

But rural life is also dangerous. Besides the large open hearths of the chimneys, wild animals, or even domestic ones like the sow from Falaise, agricultural infrastructures are prone to sometimes deadly accidents. Several tragic accounts mention death by drowning in the mill ponds. Thus, iconography hints at a rural world where children fully participate in agricultural work while being strongly connected to their families.

In the City

The medieval city is a place of intense and bustling activity. Generally, it is after the age of twelve that children enter into the service of an artisan. However, apprenticeship contracts show children as young as eight years old alongside a master who teaches them the basics of their future trade, building upon the mechanical arts already learned. In the margins of certain manuscripts, child cooks, carpenters, or blacksmiths are seen busy with difficult and thankless tasks.

The city is also where the hardships of the times are perhaps most keenly felt. The episode of the plague in 1348 contributed to the impoverishment of the urban world. Children suffer from epidemics, malnutrition, and even famine. In this context, begging becomes prevalent. The beggar will have a better chance of evoking sympathy from the nobles who practice charity by giving alms if they have a child with them.

But the city can also transform into a vast open-air playground. Left to their own devices, children and young adolescents watch the fish along the streams before diving in themselves to frolic in the water. As soon as they’re done, they rush straight to the nearby square to admire the spectacle of the bear showman. Taken over by the children for a game, the medieval city then takes on the appearance of a merry dance. In the end, the iconography reflects both the difficulties and dangers faced by children, as well as the playful or amusing nature of these merry groups of children who take over the places.

In the Castle

In the medieval castle, chivalrous and courteous education is imparted. Past the age of eight, boys are separated from their families to join the court of a lord of higher rank than their father. They then enter another universe, one of the cavalcades, stables, armories, hunts, ambushes, and masculine frolics. Illustrious children such as the King of Naples, Louis II of Anjou, are depicted in royal postures proportional to their size. Thus, if he rides a palfrey before the gates of Paris, the young king has a mount his size.

It is also at the castle that young nobles learn the art of hunting. This aristocratic practice is taught from the age of 7, although 12 seems more appropriate. In the wealthiest circles, children are spared so as not to hinder their development. As seen, children are generally tasked with brushing the dogs or preparing nets while observing their elders.

Still, within the castle, young pages receive education from a great lord to serve with honor. The life of a young page under Louis XII is not so rigid. We see him here and there playing with a small monkey, very much in vogue in the courts of the 14th century. The castle is also a place of pleasure where the child has his place. The education provided there aims to acquire the knowledge necessary for power under the guidance of a pedagogue, as we see here. Ultimately, the castle’s environment is not foreign to children.

On the contrary, they are integrated into aristocratic activities to acquire the codes and abilities to maintain their status.

Daily Life for Children in the Middle Ages

Among the numerous images featuring children, many of them offer glimpses into their daily lives. Sometimes at the center of the image and thus the focus of attention, other times on the margins, the place of the child within these representations is always rich in information that often coincides with contemporary textual sources. Thus, during childhood, dressing, playing, and eating are frequently staged in iconography.

Garment

Everything in a child’s attire is useful but also codified. From the “mantel” the placenta forms to the protective cradle, the goal is always to protect the child. Two types of clothing are identifiable during infancy. In early childhood, there are swaddling clothes. The attire may vary from one place to another (e.g., the mantellino with buttons in Italy) but shares common features. In Italy, spiral-striped shirts (= mummy) are notable, while elsewhere, the stripes appear looser.

The newborn’s trousseau is simple. Initially, the infant is wrapped in a linen cloth against the skin, further covered by a thicker fabric. The purpose of swaddling is to ensure proper body formation, which is deemed malleable at that stage. Ultimately, the newborn’s attire must be both comfortable and protective.

The transition from swaddling to a gown was gradual. Before the child walks, the arms are first freed in a half-swaddle. The gown, or cotte, comes into play before walking age, around one year, allowing the child time to become accustomed to their limbs. Once the child stands with the help of a walker, a long gown reaching the feet can be worn.

Between two and seven years old, the gown shortens to enable more extensive play and movement. From seven to fourteen years old, the clothing adjusts to size. Wearing a leather belt and boots generally signals the transition to a higher stage.

The color of the clothing is not arbitrary. Red and green are particularly favored. Red is believed to protect against hemorrhages, the plague, and especially measles. Moreover, aristocratic children wear a piece of red coral around their neck, possessing apotropaic value. Green is more associated with the idea of youth and the festivities of May.

Game

The game is present in all environments. Its purpose is to contribute to the strengthening of the child, their education, and their socialization. Thus, the phenomenon of the child alone with their toys is not a medieval characteristic.

Play primarily occurs in society. Many toys are handmade. Many of them are related to the commercial domain, such as the spinning top, the miniature dinner set, small merchant boats, or even the miniature plow. Others, of course, are related to war and chivalrous culture.

Several forms of amusement are distinguished, evolving according to age. Initially, the child learns to play with their body, like the infant Jesus playing with his foot or the little putti discovering their intimacy. Play quickly becomes collective and sometimes, frankly, scatological.

In a series of illuminations depicting children’s games, one can see little boys and girls playing while urinating in a pot. Others use objects that mimic nature, like the ball imitating fruit or the whistle imitating a bird. Outdoor games adapt to their environment (hopscotch, marbles, palaces, etc.). Another major game is the hobby horse. Faced off, two young boys imitate their elders, who truly joust.

All these games were to be played under the close supervision of a nurse or parents. Nevertheless, their function is primarily to promote the integration of children into society while playfully preparing them for their future activities.

Food

In addition to the mother or nurse, the father also played a role in the child’s nutrition. Similar to Joseph, fathers were responsible for preparing porridge made from flour to fortify the child’s body.

This flour paste, known as “papin,” was often supplemented with honeyed bread, goat milk (considered closest to breast milk), and a small amount of wine.

Various dishes were dedicated to this purpose, including special jars used as bottles and clay horns for breastfeeding. The horn, besides milk, could also deliver a small amount of wine, which may seem surprising today. However, it was heated beforehand to extract tannins known for treating infant diarrhea.

The weaning process was gradual, transitioning from breastfeeding to porridge consumption. By the age of two, children could consume a more regular diet, including boiled foods, eggs, cooked apples, wine, and poultry. They could even participate in banquets and receptions.

In iconography and literature, the crust of bread often symbolizes childhood.

Extraordinary Childhoods

The Infant Jesus

Throughout the Middle Ages, the representation of the Nativity underwent evolution. By the late Middle Ages, the scene typically unfolded in a stable where the ox and the donkey were included, despite their absence from the Gospels.

The shepherds and their animals congregated around the Holy Family to commemorate the Lord’s arrival, having received a warning from an angel. Subsequently, the Magi arrived to present gifts to the infant Jesus. The number of Magi depicted varied over time in iconography.

According to Jacques de Voragine, Melchior, depicted with white hair, symbolized gold and royalty; Gaspar, represented with red, offered incense from Asia; and Balthazar, with a black face, brought myrrh, symbolizing the Son’s eventual death. Similarly, various representations of the Virgin and Child existed.

The presentation of Jesus in the temple corresponds to a passage from the Old Testament indicating that “every firstborn male shall be consecrated to the Lord” [Exodus 13:2, 11–13]. An elderly man named Simeon received the infant Jesus. At the age of twelve, Jesus was discovered in the Temple conversing with the doctors. Upon being found by his mother, he responded, “Why were you searching for me? Did you not know that I must be in my father’s house?” [Luke 2:40–50].

Hence, medieval iconography depicted all episodes of the infant Jesus’ life.

Merlin: Half-man, Half-demon

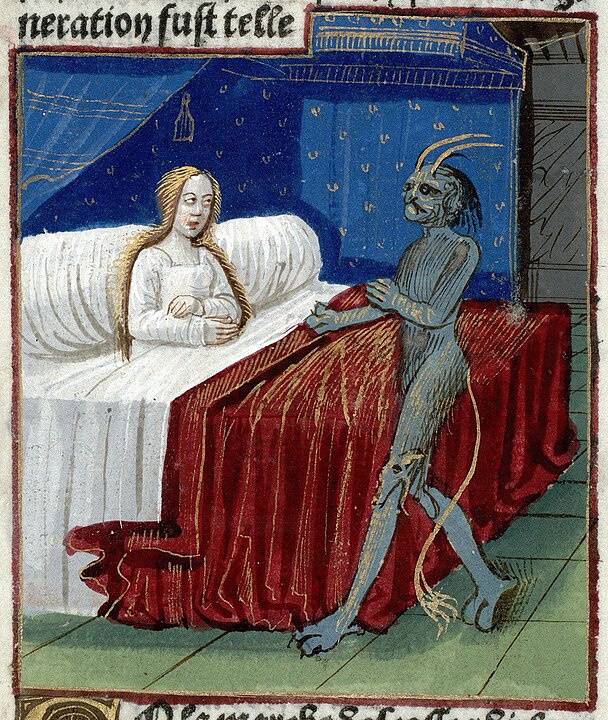

Merlin is the son of a princess impregnated during her sleep by an incubus demon. The sexual power of the demon is suggested in some illuminations by a cacophony of other demons. Merlin is, by nature, half-diabolical.

The son of a devil who deceived a virtuous woman, Merlin knows the past and the future. He reveals himself differently from birth: an astonishing newborn covered in hair, he lives secluded in a tower with two servants and his mother, who will await a witchcraft trial for two years, which could lead her to the stake.

Meanwhile, the child has been lowered into a basket to be baptized in the presence of a curious crowd that will accompany him throughout the journey. The visual procession of baptism emphasizes the integration of the devil’s son into the Christian community and thus dispels the suspicions that weigh upon him.

Two men are putting the stake together close by in a room with a low wall separating them. These preparations weigh like a threat and seem to indicate that the verdict is known in advance.

But this is without counting on the extraordinary talents that Merlin will display during the trial held at the top of the tent. Merlin, now two years old, wears an orange robe and raises his arm to defend his mother. An exceptional orator and jurist, he argues before the prosecutor and the three judges, whom he accuses in turn, revealing their secrets and denouncing their bias. He manages to have his mother’s innocence recognized.

He serves as the intermediary between the group of women and the men of law, just as he symbolized in his younger years the exchange between the top of the tower cut off from the world and the churchyard where the baptism is celebrated outdoors and in public.

The play of colors is also interesting. The orange hue of Merlin’s robe, the same color as the justice tent, highlights an essential characteristic of the character: a public figure, a man of words, Merlin saves his mother through his eloquence and upholds a higher justice.

In contrast, the yellow of the men preparing the stake symbolizes disorder in medieval times.

Lancelot: The Best Knight in the World

Lancelot is the son of King Ban of Benoic, a vassal of Arthur, and Queen Helen. He spent his early childhood surrounded by his cousins, the sons of Bohort de Gaunes. But one day, the terrible Claudas assaults his family, forcing them to flee. Upon seeing the burning castle, Ban of Benoic, his loving father, dies of grief at the thought of what will happen to his family.

In their flight, as they have just found a place to rest, Queen Helen sees the arrival of the fairy Viviane, who dangerously approaches Lancelot’s cradle. She manages to steal the young child and rushes toward a lake, where she jumps on her feet first.

From the age of three, “The Lady [of the Lake] taught him and provided him with a master who taught him how to fight and conduct himself as a nobleman.” From then on, Lancelot is not quite like his peers. At one point in his education, he argues with his tutor. Angry, the master strikes his greyhound. In response, the young and fiery knight smashes his bow over the bad master’s head. The Lady of the Lake intervenes and sides with Lancelot, who, from then on, needs no one and can judge the best and noblest behavior.

After some exploits, Lancelot goes to King Arthur’s court to receive his knighthood, a rite of passage marking entry into a higher stage. Childhood is over, making way for youth, tournaments, and chivalrous feats.