More than half a century after the race to the moon, space is once again the venue for a rivalry. China is doing everything it can to become a superpower in space as well. Already, manned and unmanned Chinese missions have passed a number of milestones. But what does this mean for the rest of the world and the previously leading space nations?

The first landing of a space probe on the far side of the moon, a rover on Mars, and a manned space station in orbit: In recent years, China has caught up tremendously in space travel and is getting closer and closer to the previous leader, the USA. China’s government leaves no doubt that it is also striving for supremacy in space—whether in Earth orbit, on the moon, or on Mars.

At the same time, however, the political divide between China and Western countries seems to be widening, at least in terrestrial matters. As a result, a new competition for space may be brewing in spaceflight as well.

China as a new space nation

Until just a few years ago, the U.S., Russia, and the EU were the undisputed pioneers in space travel. They launched the most rockets, sent space probes through the solar system, and carried the lion’s share of the International Space Station (ISS). But the skies have become more crowded in the meantime. More and more countries are launching their own satellite and space programs.

Enormous progress in a short time

At the forefront of this is China. President Xi Jinping is striving to make his country a superpower in space as well, and is well on his way to achieving this. After lagging behind the two major space nations, the United States and Russia, for a long time, China has now caught up. No other country has made so much technological progress in space in such a short time and in so many different areas. And no other country has such ambitious plans and such a good chance of implementing them.

“It’s becoming more and more clear how dominant China wants to be with regard to space and the space economy,” says Steve Kwast, a U.S. Air Force veteran and space strategist. “They see the profit margin, they see the economic revenue stream, and they see the national security implications.”

To achieve this, the Chinese government is investing huge amounts of money in the largely state-run space industry; more than 300,000 people are said to work for the Chinese space agency alone—far more than for NASA. In addition, there are semi-private companies working on behalf of the state.

From orbit to Mars

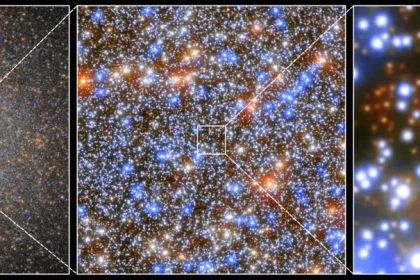

And the successes are impressive. Within a few years, China completed its own global satellite navigation system, Beidou, and set a new record for satellite launches in 2021. In one year, Chinese launchers put 55 satellites into orbit; the record previously held by the U.S. was 51 satellites in one year. The Chinese space agency is also already working on its own mega-constellation of some 13,000 Internet satellites.

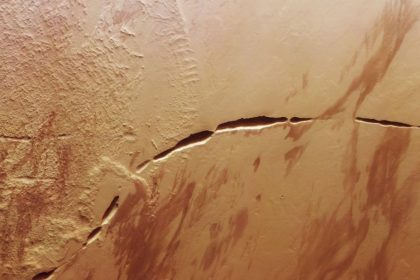

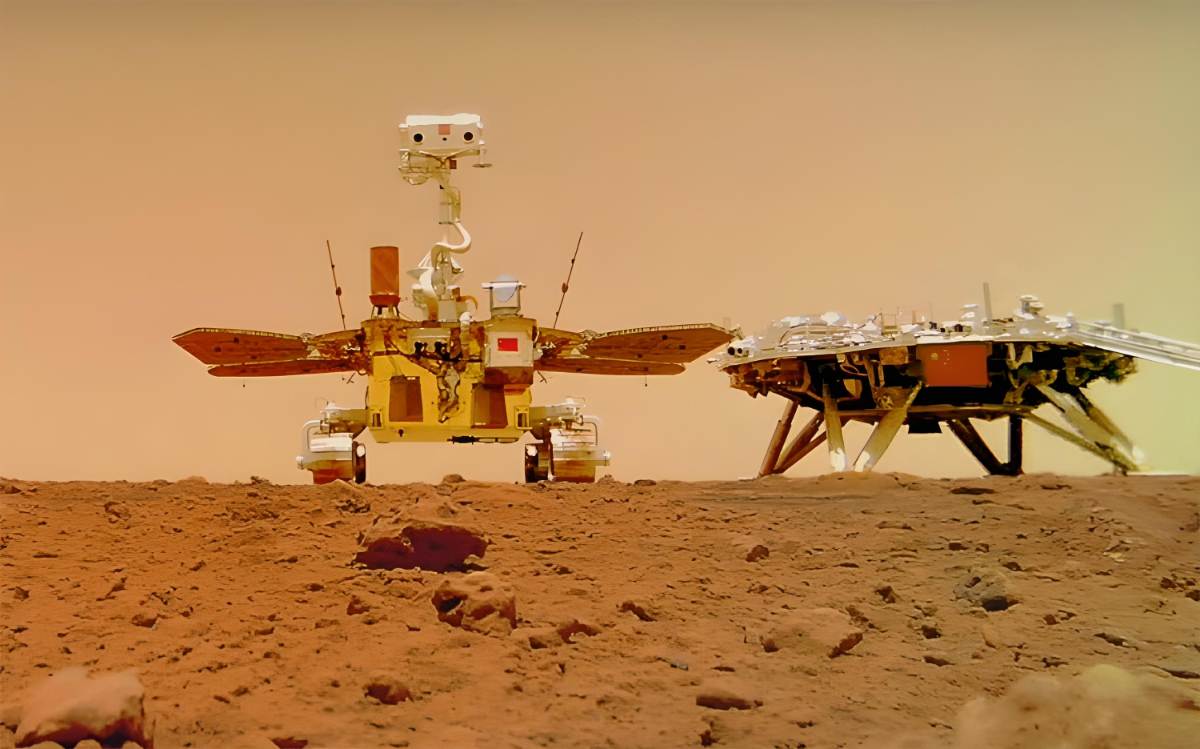

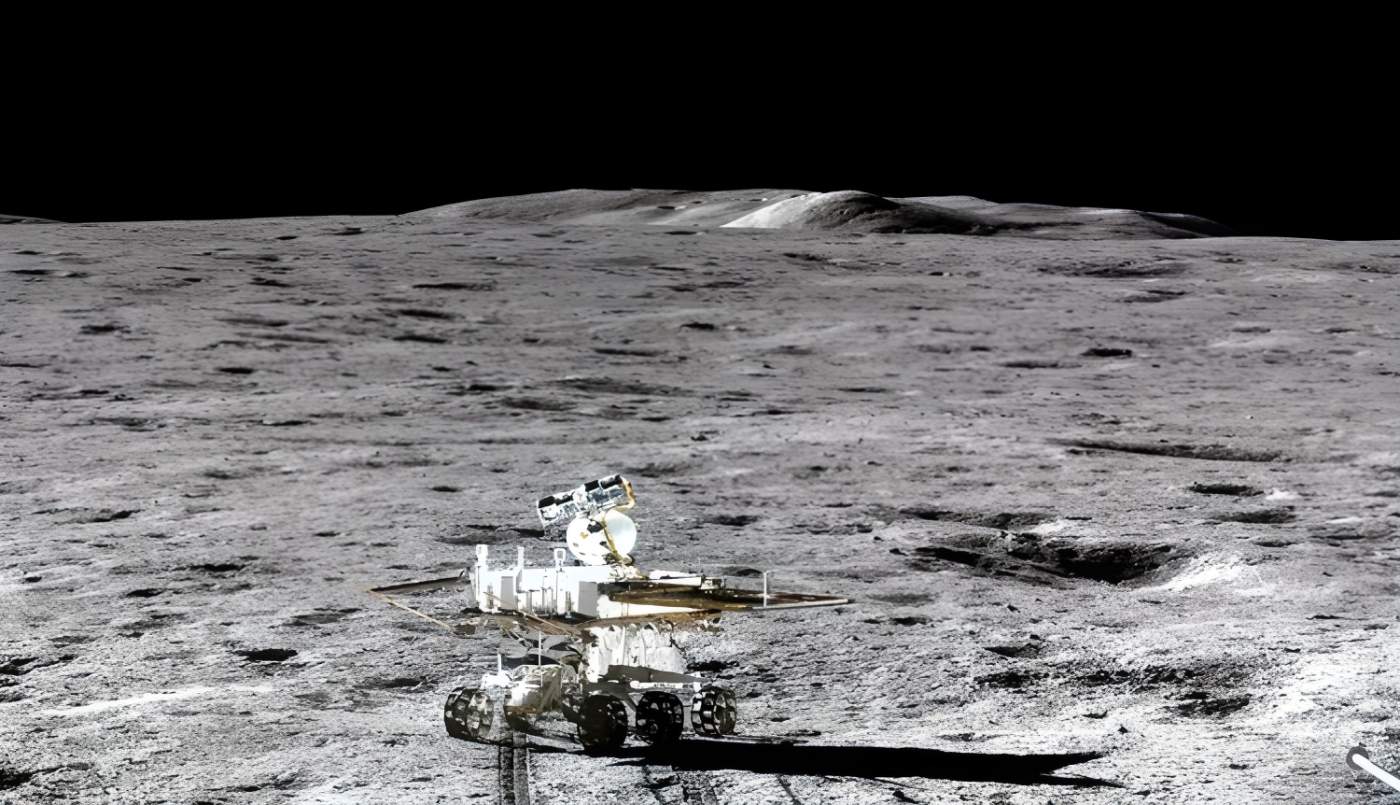

China has also reached new milestones in the exploration of the moon and Mars. Chang’e 4 was the first space probe to land on the far side of the moon in 2019. In 2020, its successor, Chang’e 5 brought back to Earth the first lunar rock samples since the Apollo missions. In May 2021, China became the only country after the United States to successfully land a Mars rover on the Red Planet with its Tianwen-1 mission. The Zhurong rover has since been exploring an area in Utopia Planitia, a plain northeast of the landing area of NASA’s Perseverance rover.

China is now also competing with the U.S. and Russia in manned spaceflight. After launching its first astronaut in 2003, the country now operates a space station in low-Earth orbit, becoming the third nation after Russia and the U.S. to do so. In April 2021, the core module of the Tiangong station was launched into orbit, followed by the first laboratory module, Wentian, in July 2022. The second laboratory module, Mengtian, followed in October 2022. 14 Chinese astronauts have already spent time at the station as part of its construction and testing.

Just the beginning

For Xi Jinping and China’s space agency, however, this is just the beginning. They see an expanding space presence and space technology as an essential part of China’s development. “To explore the vast cosmos, develop the space industry, and build China into a space power is our eternal dream,” Xi stressed in a recent “white paper” on China’s space program. The space industry is a crucial element of the national strategy, he said.

Competition for space supremacy

For decades, things in space were largely cooperative and peaceful. Exploration of the solar system and research in Earth’s orbit were primarily characterized by cooperation rather than competition. Even old archenemies like Russia and the United States worked together on joint projects like the International Space Station (ISS).

However, this was not the case for China. Unlike Russia, which did maintain close relations with the Western space nations, the country remained relatively isolated even in space. For example, the U.S. blocked its participation in the ISS out of fear of industrial espionage by the Middle Kingdom or China. There was also little interest in cooperating on space probes.

Rival blocs

But the former pariah, China, has become a full-fledged rival. Thanks to its technological advances, China has also become a power in space that other spacefaring nations can no longer ignore. China’s undisguised striving for power, but also the Ukraine war and the associated conflicts between Russia and the West, have drawn new fronts—a new cold war is brewing.

As was the case a good 70 years ago, superpowers are vying for records, technologies, and resources in space. And as in the first “Space Race” in the 1950s and 1960s, two blocs with largely contrasting ideological and political views are facing each other. “One bloc includes more authoritarian states led by China and Russia, and the other is made up predominantly of democracies allied with the U.S. and “like-minded” countries,” Alanna Krolikowski of Missouri University tells The Guardian.

A new eastern alliance?

After decades in which Russia and China barely cooperated with each other in space, a new rapprochement between the two formerly communist states now seems to be on the horizon. There are declarations of intent for future joint projects on the moon and demonstrative mutual visits by Putin and Xi to their national spaceports. An alliance would bring advantages to both: China benefits from Russia’s greater space expertise and experience; Russia, in turn, could benefit from China’s greater financial strength and more advanced technology.

However, it remains to be seen how close this cooperation will actually be. After all, Russia and China have another thing in common: Their governments are striving for global supremacy and a new old greatness for their empires. This also implies a more rivalrous than cooperative attitude with potential competitors. Some experts are therefore rather skeptical about the new “bromance” between Putin and Xi. The techno-nationalist attitudes of both states could stand in the way of genuine cooperation in space.

Return of the Sputnik trauma

For the U.S., long the undisputed leader in all areas of space, new rival China is a problem: “We are back to where we were in 1957. This is not a Sputnik moment in the strict sense, but it comes very close to its spirit,” U.S. intelligence expert Mike Rogers recently stated. “China is racing ahead in space, while we are unfortunately resting on our laurels, impressive as they may be.”

General David Thompson, vice chief of the U.S. Space Force, takes a similar view: “We are absolutely in a strategic competition with China, and space is a part of that,” he told in early 2022. China, he said, is expanding its space capabilities twice as fast as the United States. “If we don’t start accelerating our development and delivery capabilities, they will exceed us.”

The new space rivalry could become particularly problematic for the closest celestial body to us, the moon.

China’s plans for lunar missions

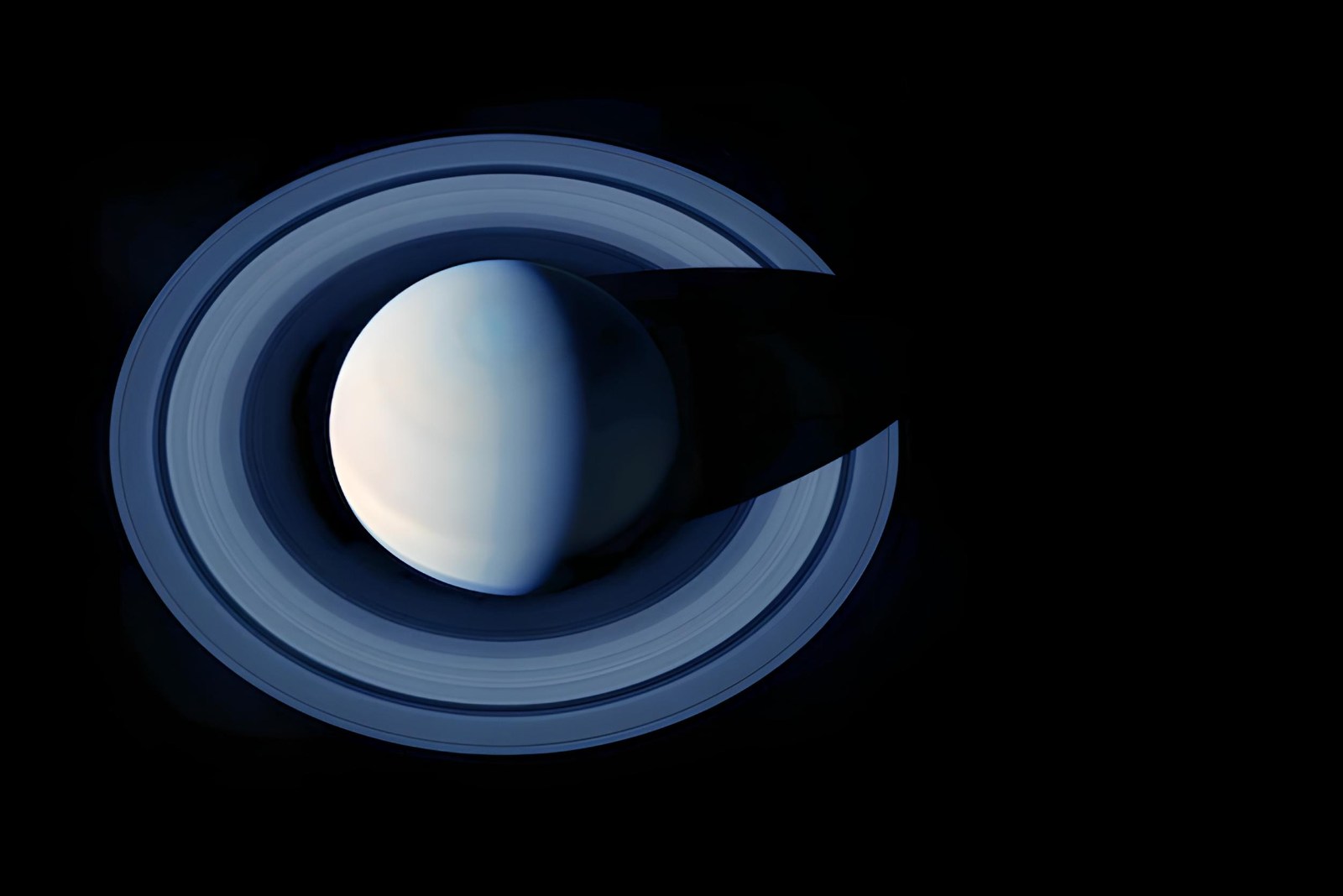

Everyone wants to go to the moon. After a break of almost 50 years, the Earth’s satellite has once again become the focus of interest in space travel. The moon also has great strategic importance as a stopover to Mars, as a location for space telescopes, and as a lucrative destination for space tourists.

And here, too, China is playing a major role. China’s lunar program initially relies on unmanned probes to test and develop technologies and locations for later manned lunar missions. The first major success came in 2013 with Chang’e 3, the first landing of a Chinese space probe and small rover on Earth’s satellite. Chang’e 4 followed in 2019 with the first landing on the far side of the moon—the first space probe ever to do so. A satellite placed at lunar Lagrange Point 2 will serve as a relay for the radio signals; a second relay satellite is to be added in 2024.

Lunar South Pole as a priority target

This means that China is present even before the USA in a lunar region that is considered particularly suitable for future lunar stations. This is because data from orbital probes suggests that there could be 3-foot-thick layers of water ice in the deep shadows of some craters in the South Pole-Aitken depression located at the lunar south pole, an important resource for future lunar astronauts. Metals and other resources could also be found in the regolith of this region.

China plans to use the Chang’e 6 lunar probe to determine whether this is actually the case. It is scheduled to launch in 2024 and take samples from the South Pole basin and bring them back to Earth. The two follow-up missions, Chang’e 7 and 8, are also to land in this region and conduct geological investigations and technical tests there. Among other things, experiments are planned on the use of regolith as a building material.

But China also wants more than just robotic flying visits to the Earth’s satellite; its long-term goal is a manned lunar base. According to current plans, the unmanned construction phase for such a station is to begin around 2030, and the first Chinese astronauts could then land in 2036. According to the Chinese space agency, the lunar base will primarily serve research purposes and will also be open to other nations.

A joint lunar station between Russia and China

The first partner for this venture could be Russia. In the summer of 2021, the Chinese and Russian space agencies signed a memorandum of understanding for a joint International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). In July 2022, Roscosmos head Dmitry Rogozin told Russian broadcaster Russia-24: “We are now almost ready to sign the contract for a joint lunar base with China.”

In parallel, Russia has resumed its Luna program, which had been paused for nearly 50 years. In September 2022, the Luna-25 spacecraft was scheduled to initiate the Russian return to the moon, also landing in the lunar south polar region. The piquant thing about this is that the newly launched Russian Luna missions were originally planned in cooperation with the European Space Agency (ESA). However, the latter terminated the cooperation after the start of the Ukraine war. Luna 25 is scheduled to launch no earlier than 2023.

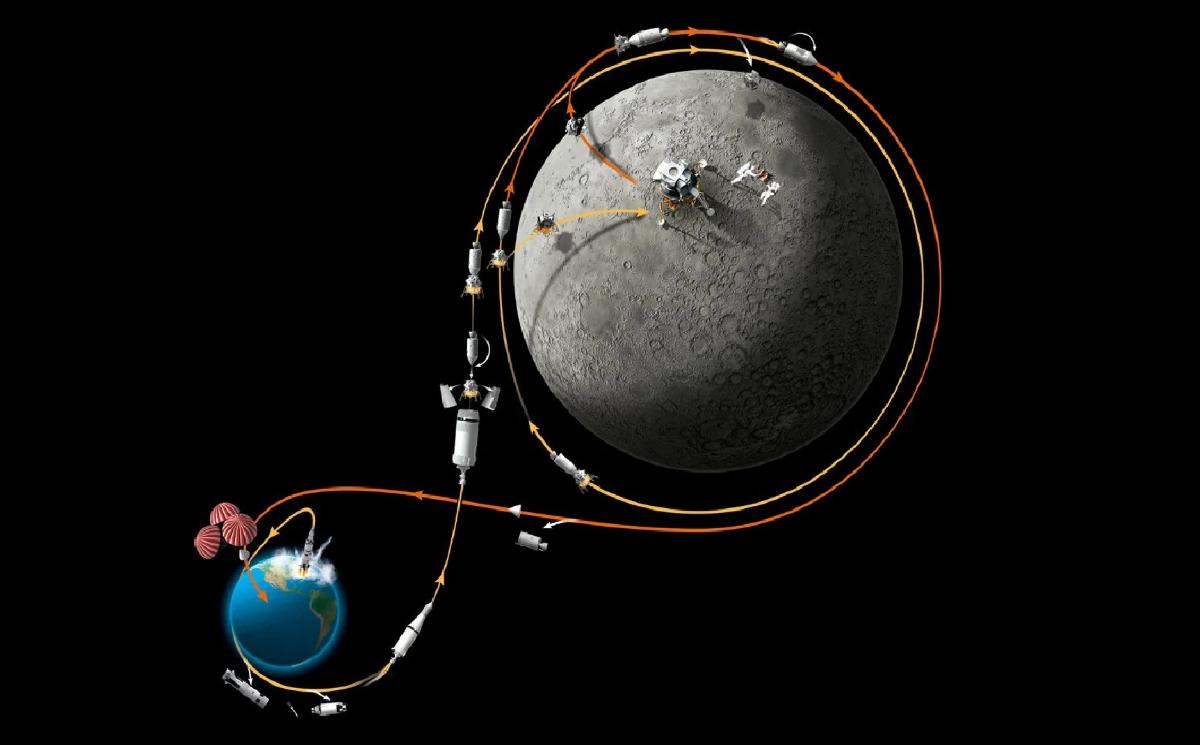

Dispute over the Artemis Accords

According to the report, lunar exploration is also seeing a new edition of the old space race, with the Chinese-Russian ILRS on the one side and the Artemis program of the U.S. and Europe on the other. The latter plan is to land astronauts on the Earth’s satellite again as early as 2025 and to launch a lunar space station into lunar orbit. This could threaten a conflict over lunar sites and resources, in part because space law has so far not contained any clear regulations for this scenario.

To change this, the U.S. has drawn up the so-called Artemis Accords, a set of agreements intended to regulate the dealings of various players on the moon. In the Accords, signatories agree to abide by the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, avoid mutual interference, share information, and use the most compatible technologies possible. “What we’re trying to do is make sure that there is a norm of behavior that says that resources can be extracted and that we’re doing it in a way that is in compliance with the Outer Space Treaty,” Bridenstine says. In addition to the U.S., 20 countries have signed the treaty so far.

But China’s government sees the Accords as an attempt by the U.S. to impose regulations on other space-faring nations, and China, in particular, that unilaterally benefit U.S. interests. “The Accords are an attempt to seize the moon for themselves and colonize it,” criticized Chinese military expert and commentator Song Zhongpin in the Global Times in 2020. Reports on Chinese state broadcaster CGTN were in a similar vein. However, there are also Chinese experts on space law who concede that international guidelines for lunar exploration and exploitation are needed and that the primarily bilateral accords could at least be a precursor to those.

In any case, one thing is clear: The next few years will see competition for lunar milestones, sites, and resources, and China will be at the forefront.

China’s new Tiangong space station

In parallel with the new race to the moon, the balance is also shifting in manned spaceflight in Earth orbit. After Russia and the USA as leading operators of space stations, China now also has its own space station in Earth orbit. In principle, there was little else for the country to do because, in 2011, at NASA’s instigation, China was expressly excluded from participating in the International Space Station (ISS) because industrial espionage was feared.

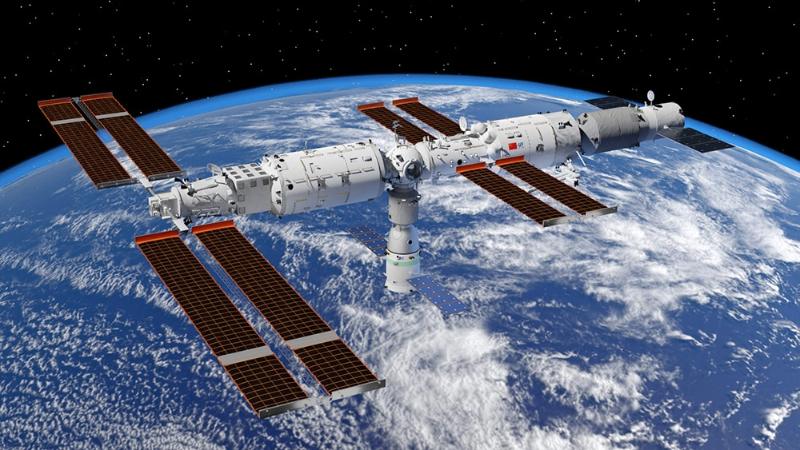

Tiangong is modular and as big as Mir

Like the Russian Mir space station and the ISS, the Chinese Tiangong station has a modular design and is gradually being added to orbit. It orbits in low Earth orbit between 340 and 450 kilometers above the Earth, roughly the same range as the ISS. When it was completed in October 2022, the station consisted of a core module and two laboratory modules and weighed around 80 to 100 tons. In terms of size and weight, it is roughly equivalent to the former Russian Mir space station but has only one-fifth of the mass of the ISS.

The station’s core module, Tianhe, was successfully launched into orbit by a Long March 5B launch vehicle on April 29, 2021. The module, which is nearly 17 meters long, contains a service section with life support systems, a power supply, propulsion systems, and systems for position and navigation. The second part contains quarters for three astronauts, computer and control systems, and communications equipment. In addition, the Tianhe module has a docking system and a robotic arm.

The laboratory modules

On July 24, 2022, another mission brought the first of two laboratory modules to the station. This initially docked to the docking site located at the forward end of the core module so that the two modules are in line. However, subsequent transposition gave the approximately 20-ton laboratory module its final position transverse to the core module. Wentian contains quarters for three additional astronauts and space for scientific experiments, as well as a second robotic arm and backups for key core functions such as navigation, propulsion, and attitude control.

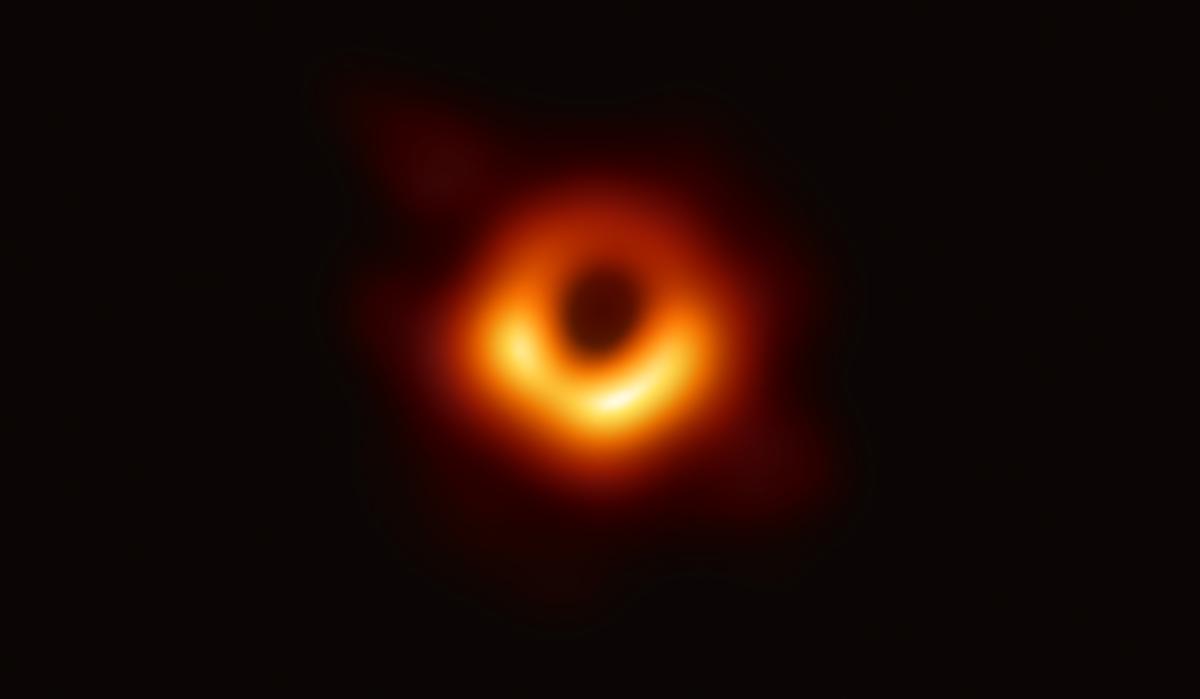

The Wentian laboratory module also contains the station’s future main airlock. Astronauts will disembark through it when they need to perform outboard missions. These will be necessary, for example, to maintain and service measuring instruments attached to the outside of the station in the future. The laboratory module has special holders for this purpose, into which large instruments can also be latched. These could include a small reflecting telescope from 2023 and, from 2027, a four-ton instrument for measuring cosmic radiation, which was developed with the participation of European scientists.

In October 2022, the basic structure of the space station was completed with the second Mengtian science module. This module contains additional space for experiments as well as an airlock for supplies and other payloads. Unmanned supply capsules of the Tianzhu type can dock with it. It is unclear to what extent the docking mechanism, which is based on the Russian system, is also compatible with the systems of the ISS and the space capsules of other countries, as, with many technical details, China’s space agency is keeping a low profile.

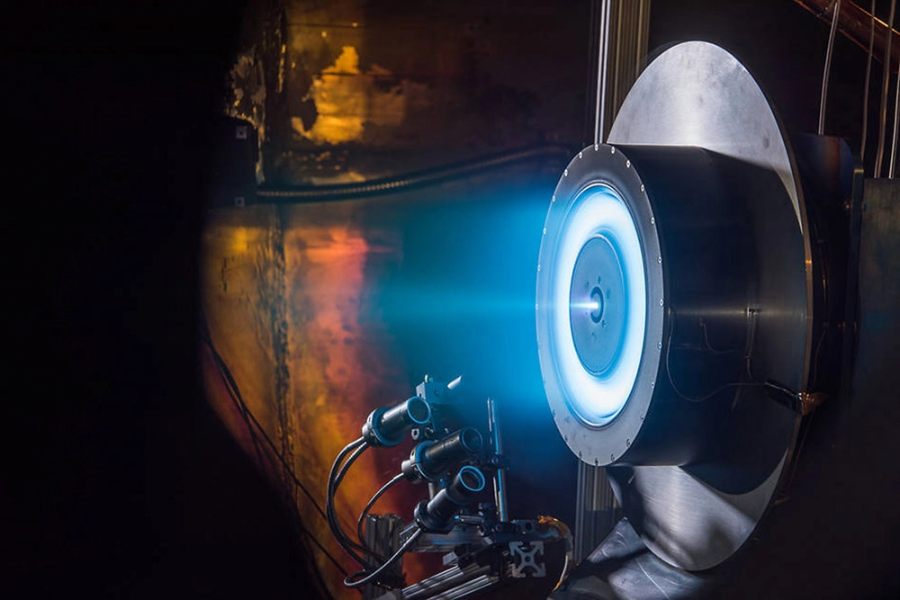

First ion propulsion system in manned space flight

Image: NASA

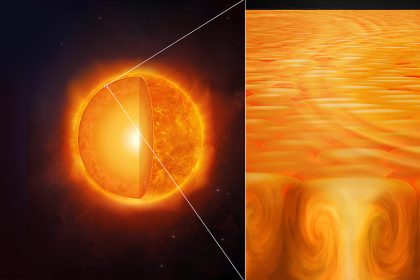

The Tiangong station’s propulsion system is a major feature. In addition to classic thrusters, the Tianhe core module also has an ion propulsion system—the first manned space vehicle ever to do so. The four Hall-effect thrusters generate their thrust from a stream of positively charged particles, presumably xenon ions, accelerated by an electric field. A ring current of electrons controlled by a magnetic field provides additional thrust and neutralizes the ion current after it exits the propulsion nozzle.

The advantage of such ion drives is their small size and long operating life. They can generate less thrust than chemical thrusters, but a small amount of xenon gas is sufficient to propel them. On the Tiangong space station, the Hall thrusters are expected to operate for at least 15 years and maintain the station’s orbital altitude at a stable level. One disadvantage of ion propulsion, however, is the highly corrosive effect of the accelerated ions. To prevent them from damaging the thrusters and the space station’s hull, they are surrounded by an additional shielding magnetic field and a protective ceramic shell.

Other nations may also join in

At present, China’s new Tiangong space station is mankind’s second “outpost,” alongside the ISS, but it could soon be the only one. That’s because the ISS is already relatively old, and its funding is on the line. In the wake of the Ukraine war and increasing conflicts with Western countries, Russia has announced the end of its participation in 2024. Whether the International Space Station will continue to be operated then, and in what form, is still unclear.

In the future, however, Tiangong—the “Heavenly Palace”—could also become a place of international cooperation, the Chinese government emphasizes. Some of the scientific experiments currently installed on the space station are already being carried out in cooperation with other countries or were developed entirely by research institutions in Europe. Among others, Norway, Belgium, Switzerland, and Germany are involved. There is also particularly close cooperation between China and the Italian Space Agency. It is developing the cosmic ray measurement instrument, which is expected to be installed in 2027.

“After our space station is completed in the near future, we will see Chinese and foreign astronauts flying and working together,” Ji Qiming of China’s manned spaceflight agency said in a recent press conference. The participation of astronauts from other countries is guaranteed, he added. Whether and in what form this participation will take place, however, remains to be seen.

What also seems clear, however, is that if China’s rapid development in space travel continues at this rate, most other countries may have little choice but to join in. “The exploration of space will go ahead, whether we join in it or not,” said then-U.S. President John F. Kennedy in 1962 during his famous moon speech in Texas.