One of the most important religious and familial festivals in France is Christmas (French: Noël). The cycle of Noël, which starts on December 25th and ends on January 6th (the Feast of Epiphany), consists of 12 days. On December 24th, there will be a church service and a dinner as part of the celebration. The French Christmas customs include nativity displays, exchanging presents and greeting cards, and a Christmas tree. There are Christmas markets in a lot of French cities as well. A large percentage of people who don’t identify as religious also celebrate Christmas, even though it is a religious festival. Family values, not Christian ideas, are what most French people connect with this tradition.

-> See also: 48 Countries That Celebrate Christmas Widely

History of Christmas in France

France, like the rest of Europe, has a long tradition of celebrating Christmas. Nevertheless, no similar festivity was observed by early Christians. It was not until the Church began to doubt the date of Christ’s birth—a topic that is absent from the Gospels—in the second century AD. The considered dates ranged from January 6th to April 10th, among others. Emperor Constantine did not decide to celebrate Christmas on December 25 until the fourth century, between the years 330 and 354, and Pope Liberius finally formalized the tradition in 354. It was recorded in the year 354 that Christ was born on December 25th.

This was clearly not an accident of fate; on this very day, Christians were vying for adherents away from Pagan worship. December 25 was a significant occasion in the Roman Empire (of which France was a long-term member) celebrated as the “Birthday of the Invincible Sun” (Dies Natalis Solis Invicti). By syncing the conclusion of the Saturnalia with the birthday of the god Mithras, whose worship was prevalent in Rome at that era, Emperor Aurelian selected and instituted this date. To counter this religion, Christians pointed to Jesus Christ as the “Light of Justice.” As the practice of celebrating Christmas on December 25th became more common, it eventually made its way to Gaul in the 5th century. The date has been entirely identified with Christian tradition since Emperor Theodosius established an edict in 425 mandating the global commemoration of Christ’s birth.

Christmas Traditions in France

Christmas Tree

Just as in the rest of Europe, the Christmas tree is a major part of the French holiday season. Christmas tree decoration with evergreen branches is a practice that originated in ancient times and was embraced by Christians in the seventh century. A fir tree decorated with red apples later on, in the 11th century, came to represent the tree of knowledge in Christmas puzzles centered on the idea of paradise. But it was probably in the 16th century in Alsace when the current idea of a Christmas tree first emerged, and it quickly spread throughout Europe. It wasn’t until 1738 that the first Christmas tree was set up at Versailles, France. The ordinary people followed the bourgeoisie and royal court in adopting the custom. Handmade ornaments (such as garlands and gilded nuts) adorned the trees until the mid-nineteenth century, when glass Christmas ornaments—which are still popular today—emerged. Artificial trees were manufactured in the twentieth century.

The current yearly sales in France for real Christmas trees are close to five million. France, namely the Morvan area in Burgundy, grows over one million of them.

Père Noël and Gifts

Presents for the new year shifted from being given at New Year’s to being given around Christmas, especially to children, by the 19th century. Even though he didn’t exist until the 19th century, the figure known as “Père Noël” (“Father Christmas”) has become inseparably linked with Christmas presents. Saint Nicholas, whose feast is observed on December 6th and who is revered as the patron saint of children, served as an inspiration to him. Tradition has it that during the nights of December 5 and 6, he visits every country, stopping to fill the shoes left by children by the fireplace with presents. But only the nice and obedient children get presents; the bad kids get coal and a visit from Saint Nicholas’s “dark” sidekick, Père Fouettard. This custom is still alive in several parts of northeastern France, especially in Lorraine.

The French did not hold Père Noël in high esteem until the 20th century. But in the 1950s, Père Noël became the main representation of Christmas, impacted by the rising stardom of the American Santa Claus (whose ancestor was actually Saint Nicholas). Père Noël was branded as a Pagan and heretic by the Catholic Church, which vehemently opposed his arrival, accusing him of leading people astray from the holiday’s genuine essence. Even Père Noël was publicly burned in front of the municipal church in Dijon in 1951. Some Catholic households still teach their children that the Baby Jesus, not Père Noël, gives presents on Christmas Day.

Although most people wait until Christmas Eve to exchange presents, some adults do so the night before the holiday meal. The Christmas tree is a common hiding place for children’s presents. Père Noël wasn’t the only Christmas figure in France until he became famous nationwide. There was Père Chalande in the east, especially in Savoy; Barbassionné in Normandy; and Père Janvier in Burgundy. Aunt Ari, a kind fairy, was believed to be the one who bestowed Christmas presents in Franche-Comté.

French Christmas Meals: Réveillon

- Roasted turkey with chestnuts

- Foie gras (liver of a duck or goose)

- Yule Log cake (“Bûche de Noël”, a tender chocolate sponge cake)

- Brédele (biscuits or small cakes, famous in Alsace)

- Thirteen desserts (common in Provence)

- Cougnou (bread baked during Christmas, popular in the north and east of France)

- Shellfish (common in Brittany)

- Locally made snails accompanied by the Burgundian wines

On the evening of December 24th or 25th, upon the family’s return from midnight Christmas Mass, a sumptuous celebratory feast, called a “réveillon,” was traditionally held. Even though hardly everyone goes to Mass anymore, the habit of having a big family meal has not altered. Most French people place a much higher value on the Christmas feast than the equivalent New Year’s feast, often known as “réveillon.” Oysters, smoked salmon, roasted turkey with chestnuts, and foie gras are usual table fare. Chocolate and the classic “Yule log” are the two most beloved sweets.

The menu changes depending on the location of France since each region has its own culinary customs. Various shaped and flavorful cookies called “brédele” are famous sweet desserts in Alsace. Commonly served in Provence Christmas feasts are the so-called “thirteen desserts,” which represent the twelve apostles around Jesus. A sweet bread with chocolate pieces or raisins called “cougnou” is popular in the north and east of France. Its form is like a swaddled baby Jesus. Meals using a variety of shellfish are commonplace on Brittany Christmas menus. It is traditional to accompany the best Burgundian wines with a dish of locally made snails cooked in a particular manner while visiting Burgundy.

See also: All 15 Countries That Don’t Celebrate Christmas

Christmas Markets

Just as in many other European nations, the so-called Christmas markets (French: Marché de Noël) are organized in France during the latter months of the year (November to December). The practice had a renaissance in the early 20th and early 21st centuries, while its origins are in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Typical vendors at these markets offer handcrafted goods, regional specialties, holiday decorations, and souvenirs from their quaint wooden chalets. There are usually a lot of lights and music to set the mood for Christmas, and you may even discover a temporary ice rink or Ferris wheel at these markets. As a common feature of Christmas markets, street concerts and entertainment are often arranged.

The Strasbourg Christkindelsmärik, France’s most famous and oldest Christmas market, dates all the way back to the 16th century. From 1992 onwards, Strasbourg has been home to a multitude of Christmas festivities, including the historical market, all unified under the banner of “Strasbourg— Capital of Christmas.” The Alsace area, and Provence in particular, is known for its many Christmas markets. Paris has a number of Christmas markets every year. Some of these venues include the Tuileries Garden, the plaza in front of La Défense, the area around Notre Dame Cathedral and City Hall, and others. In 2017, the Champs-Élysées Christmas market was definitively dissolved by the municipal council.

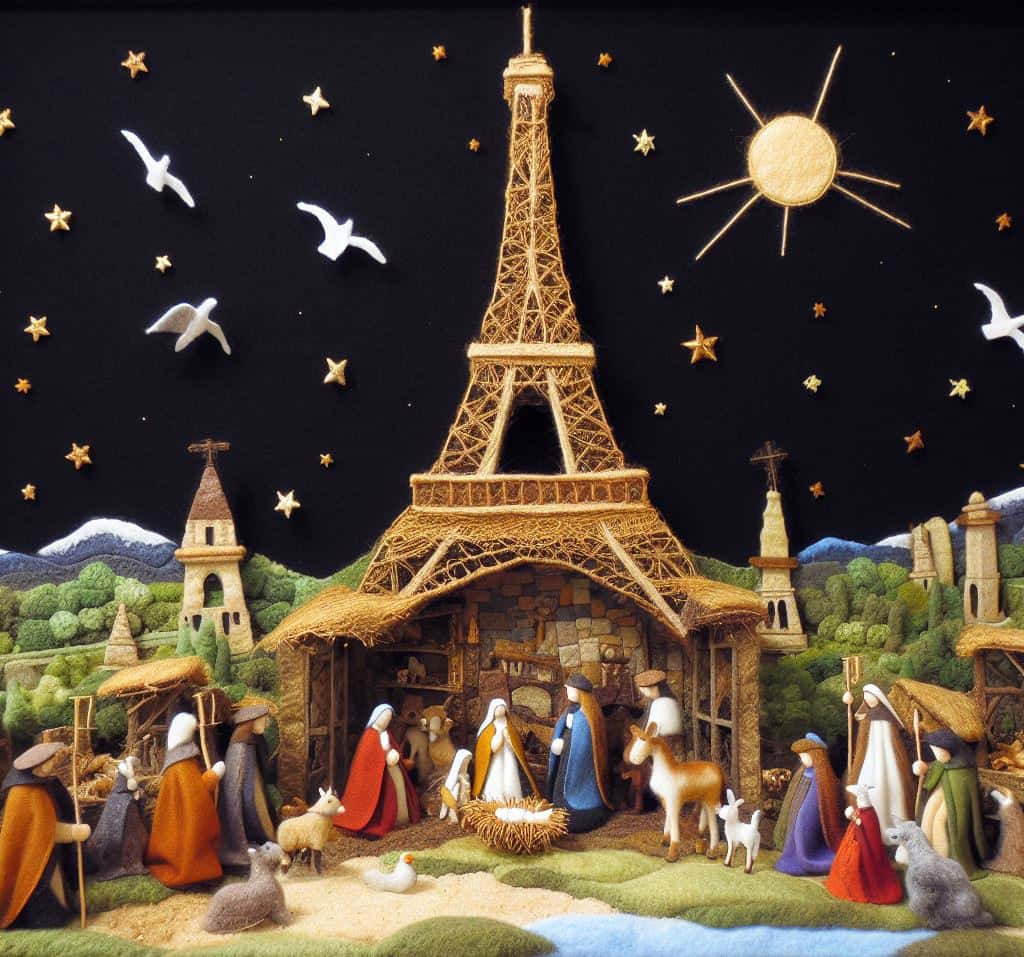

Christmas Crèche: Nativity Scenes

The Christmas Nativity scene, also known as the crèche de Noël in French, is another long-standing French custom. According to legend, the Italian mystic and friar Francis of Assisi (1181–1226) was the one who initially had the villagers act out the Nativity scene in the church at Greccio, portraying the roles of Mary, Joseph, the baby Jesus, the magi, and other figures from the Gospel. The practice of constructing Nativity scenes, which originally had live performers but later included clay, wax, and wooden figurines, eventually made its way to southern France and Italy.

Naples was the birthplace of the tradition of making Nativity scenes in private residences as well as public churches in the 17th century. Despite the prohibition of Christmas Mass and Nativity displays by the anticlerical laws of the French Revolution, this practice eventually became widespread in France. For the purpose of simple concealment, believers started crafting miniature versions of the Nativity scenes they saw in churches out of bread dough or papier-mâché and began replicating them at home.

Production of such figurines became commonplace in Provence, where this new ritual became especially popular. Their name evolved into “santons” which means “little saints.” Over time, new representations of biblical figures appeared alongside the old, with santons increasingly representing common Provencal people who came to honor the baby Jesus. The French continue to adore these artisanal, colorful figurines. You may find special santon festivals in several places in Provence, and even outside of the area, at almost every Christmas market.

These days, most people choose to display Nativity scenes at churches, whereas “home” Nativity displays are becoming more rare. Even French cities used to display Nativity displays on their streets until quite recently. But this practice has recently become the subject of debate, with some arguing that religious symbols like Nativity displays violate secular state ideals. Those in favor of seeing Nativity scenes as cultural customs that celebrate France’s history rather than religious symbols make a compelling case for this approach.