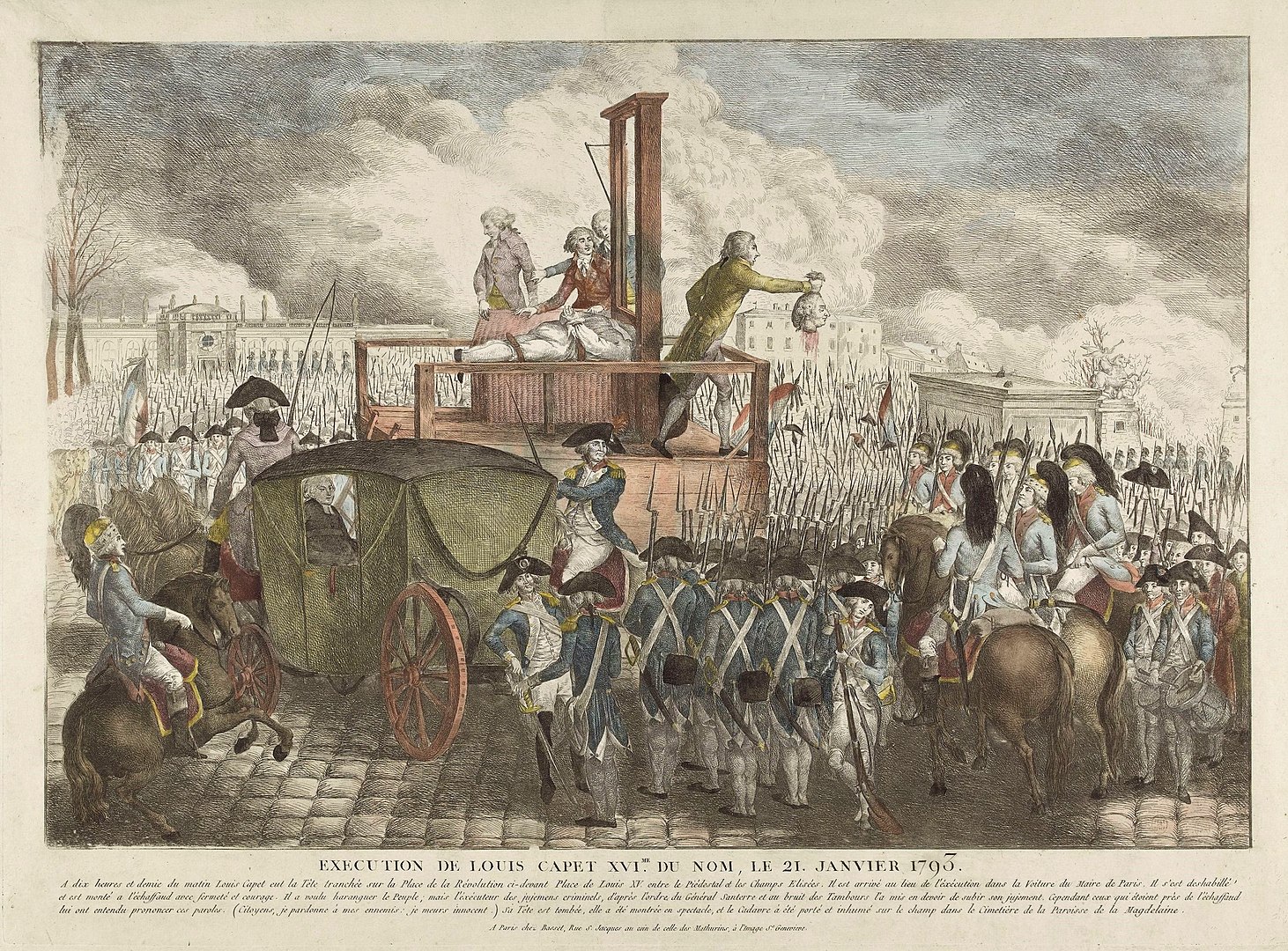

The period of the French Revolution is often primarily seen as a violent confrontation between two orders, the Third Estate and the nobility, with the execution of Louis XVI in 1793 being a focal point. The religious factor is somewhat relegated to the background. However, the clergy is also an order, at least as powerful as the nobility, and, more importantly, religion holds a central place in a deeply religious France and within a monarchy based on divine right. We will thus address the relationship between the French Revolution and religion, beginning with the situation before 1789.

- Jansenism and the Revolution

- The French Clergy on the Eve of the Revolution

- Protestants and Jews

- Religious Practice in France

- Cahiers de doléances: The Clergy, and Religion

- “It was those damn priests who made the Revolution”

- Night of August 4th

- Rise of Tensions

- Civil Constitution of the Clergy

- Constitutional Oath and the Explosion

- Dechristianization

Jansenism and the Revolution

The crisis of Jansenism left its mark on the France of the Ancien Régime, particularly through the papal response with the Unigenitus bull, which reignited Jansenism even within the Parliaments under the reign of Louis XV, where Jansenism and Gallicanism intertwined in opposition to papal influence. For a time, this “parliamentary party” gained momentum, even achieving the expulsion of the Jesuit rivals in 1764. However, Jansenism had to yield to the blows of Maupeou, who quashed the rebellion of the Parliaments in the early 1770s.

These various crises tore the French Church apart, and although Jansenism was ultimately defeated, it had nonetheless spread its ideas widely and was seen as one of the inspirations for the Revolution. As for the clergy, it found itself acting as “agents of the king.”

The French Clergy on the Eve of the Revolution

Officially, the clergy was considered the first estate of the kingdom, but the reality was more complex. By the late 1780s, there were an estimated 130,000 members of the clergy, about 2% of the French population. This included a regular clergy, two-thirds of which was female, and a highly unequal secular clergy, with bishops forming a “general staff” and a large number of parish priests, vicars, and chaplains making up the rest.

The clergy played a central role in society at all levels, starting with parish registers (a goldmine of sources for historians) and much of the education system. They also held a monopoly over charity and assistance. As an estate, the clergy enjoyed numerous privileges, both judicial and fiscal, and was one of the largest landowners in the kingdom.

However, the clergy was deeply divided on the eve of the Revolution, the most significant rift being between the upper and lower clergy, with the former enjoying far more privileges. One could even speak of a crisis within the French clergy, caused by these inequalities and the lingering effects of the Jansenist quarrel. One sign of this crisis was the sharp decline in clerical recruitment, both regular and secular, with monastic orders being the most affected.

In an atmosphere of desacralization of the monarchy, the clergy attempted to oppose all “bad books” by reinforcing censorship through several ordinances in the 1780s. The problem was that the king did not support them in this effort! It seems that, between the Church and the Enlightenment, the king had chosen the latter, even in education, which experienced “secularization” following the expulsion of the Jesuits, much to the dismay of the bishops.

Protestants and Jews

France was predominantly Catholic, but the existence of minorities should not be overlooked.

The situation of the Protestants was mixed, with persecution during the reign of Louis XIV followed by some optimism during the early reign of Louis XV. Ultimately, they continued to live in secrecy until two years before the Revolution, with the Edict of Tolerance in 1787.

Prejudices against Jews remained strong at the end of the Ancien Régime, and the issue of their emancipation was only raised in a few restricted circles. The clergy largely despised them, and mercantile and economic circles were resolutely hostile. Despite the influence of the Enlightenment and some improvements in the second half of the 18th century, Jews were still subject to severe discrimination on the eve of the Revolution.

Religious Practice in France

Religion played a central role in the collective life of Ancien Régime France, even setting the rhythm of life. However, secularization was gaining ground, particularly through the growing prevalence of secular festivals.

The situation seems more complex than has often been portrayed: France was generally thought of as deeply religious and devout, “broken” by the revolutionary rupture. It is difficult to present a unified picture: some regions remained highly devout, others much less so, and still others were influenced by a “poorly rooted” Protestantism. This diversity would later manifest itself in the reactions to the revolutionaries’ religious policies, especially regarding the process of dechristianization.

Thus, the religious situation in France on the eve of the Revolution was complex. The clergy was divided and relatively weakened, religious practice was uneven, the Protestant minority remained solid, and the influence of the Enlightenment was growing. It is, therefore, no surprise that this complexity would resurface when the Revolution broke out.

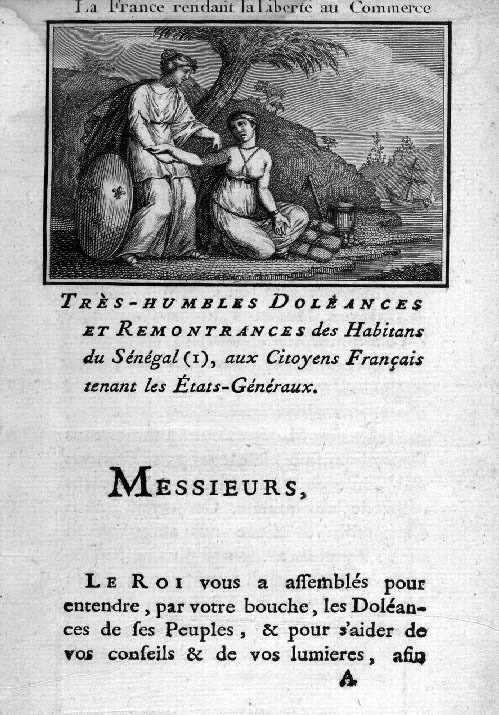

Cahiers de doléances: The Clergy, and Religion

The Estates-General were convened at the end of 1788 to meet on May 1, 1789. It was during this election campaign for deputies that the cahiers de doléances (grievance lists) were drafted, totaling 60,000, written by rural communities and urban professional groups.

Religion, especially the clergy, is a topic addressed in these cahiers but not among the primary concerns (only a tenth according to Mr. Vovelle). Notables from the West and Franche-Comté regions were highly critical of the clergy, who in these areas exerted strong control over the morals of rural populations. It was also in the West where demands for the abolition of the tithe and regular clergy were most common, despite these not being the regions where the tithe was highest or religious figures most numerous. Conversely, in the Southwest, where the tithe was at its highest, only its reform was requested.

As for the issues that foreshadow the future Outline of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the most radical measures of the Constituent Assembly (such as the complete sale of Church property), the demands were concentrated in a continuous zone stretching from the western Paris Basin to Brittany. In these regions, the notables of the Third Estate were the most anti-clerical, and it was also here that counter-revolutionary uprisings would be most significant.

However, the geography of the Cahiers de doléances differs when addressing more strictly religious matters (rather than ecclesiastical ones), such as the reduction of the number of religious holidays. The most vocal regions in this regard were the Mediterranean basin, as well as a Picardy/Lyonnais zone, including the Paris region. These areas would later be among the most affected by de-Christianization.

Regarding the clergy itself, the grievances partly reflect its internal divisions. Most of the clergy’s cahiers defended privileges, the religious monopoly, and condemned the tolerance edicts. However, a few voices from parish priests sought to improve their social status. They were supported in this by some of the village cahiers from the Third Estate.

Nevertheless, none of these Cahiers de doléances questioned religion itself as a whole.

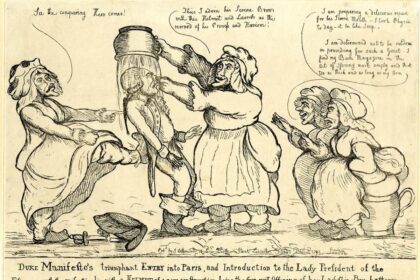

“It was those damn priests who made the Revolution”

This famous quote is attributed to an anonymous aristocrat, and while it shouldn’t be taken literally, it aptly reflects the events of the spring of 1789. First, we must consider the role of the clergy (in its diversity) at the Estates-General, then examine the actions of its members from the opening of the Estates-General until the night of August 4, 1789.

At the Estates-General, the clergy was represented by 291 deputies (out of 1,139), the majority (more than 200) being parish priests. There were only 46 bishops representing the clergy. Most of the lower clergy members supported change (though there would later be opposition between Abbé Grégoire and Abbé Maury).

During the heated debates of the Estates-General starting on May 5, 1789, parish priests played an increasingly important role as the Third Estate resisted the decisions of the king and the pressures from the nobility and high clergy.

Following Mirabeau’s initiative on June 12, three and then sixteen priests left their order to join the Third Estate; among them was Curé Jallet, who, when reproached by the prelates for this defection, replied, “We are your equals, we are citizens like you…”

At the same time, on June 17, 1789, under the influence of Abbé Sieyès, the Estates-General transformed into the National Assembly. Two days later, the clergy, by a majority of its members, decided to join the Third Estate, while the nobility sided with the king. This led to the Tennis Court Oath on June 20, 1789, again with Abbé Sieyès playing a central role, alongside figures like Abbé Grégoire. However, the clergy’s adherence to this movement should be tempered, as it remained divided, especially among prelates, still attached to privileges. And in the rising context of insurrection, particularly in rural areas, members of the high clergy were not spared.

Night of August 4th

Events were accelerating, and the king was overwhelmed. On July 9th, the deputies proclaimed the National Assembly as “constituent.” On July 14th, 1789, the Bastille was stormed. The movement spread to the countryside, resulting in the Great Fear.

It was in this both turbulent and euphoric context that the famous night of the abolition of privileges occurred, although it had been well prepared in advance. During this all-nighter on August 4th, 1789, the clergy members were far from inactive, as they were part of the privileged class. However, there was sometimes an escalation of generosity from certain members of the old order or the nobility, with reciprocal proposals. For instance, the abolition of hunting rights was proposed by the Bishop of Chartres, to which the nobility responded with the idea of abolishing the tithe.

The consequences for the clergy were significant, with decisions affecting them both directly and indirectly. The abolition of feudal dues also impacted chapters and abbeys, and the abolition of privileges as a whole deprived the clergy (which officially ceased to exist as an order) of its fiscal privileges. The clergy was then more directly affected by the elimination of the casuel (payments by the faithful for religious services), proposed by parish priests, and, of course, the abolition of the tithe. The latter, even contested by Sieyès, had the most consequences as it required the state to provide for the clergy, who had lost most of their income necessary for conducting religious activities.

In the weeks and months following, there was still a sense of unity and some euphoria, aided by the context. Religious and revolutionary celebrations took place together, and priests assumed responsibilities, especially in municipal structures. The nobles were viewed with more suspicion than the priests. This “honeymoon” period lasted at least until the spring of 1790, despite some tensions and the emergence of real divergences during the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen on August 26, 1789.

It was ultimately the Civil Constitution of the Clergy on August 24, 1790, that would ignite the situation…

Rise of Tensions

Despite the dissolution of the clergy as an order and the participation of many parish priests in the first decisions of the Constituent Assembly, an anti-religious sentiment seemed to be growing in the country by the end of 1789. Indeed, “the happy year” was not as peaceful as it was long thought, and the elements that would constitute the religious crisis were coming into place.

It began with decisions like the temporary suspension of religious vows (October 28, 1789) and the nationalization of church property (November 2), while at the beginning of 1790, the citizenship of non-Catholics, Protestants, or Jews was being debated.

Then came the debate on religious freedom during the drafting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in August 1789. The discussions were heated, ultimately resulting in Article 10: “No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law.”

As the end of the Constituent Assembly approached, some unsuccessfully tried to impose an article making Catholicism the state religion or the “national religion.” On April 12, 1790, Dom Gerle even requested that Catholicism be the only public religion, sparking an outcry, as the deputies sought instead to place all religions on equal footing.

The suspension of solemn vows aimed to attack the chapters, as the revolutionaries believed that freedom should not stop at the doors of the convents. The Jean-Baptiste Treilhard decree of February 13, 1790, allowed male and female religious members to be released from their vows and to leave their monasteries or convents, granting them a pension. Congregations were spared for the time being, although they were affected by the confiscation of their property, as was the case with all clergy assets. However, teaching orders were dissolved on August 18, 1792.

Civil Constitution of the Clergy

The major decision on the religious question was undoubtedly the passing of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. This aimed to organize the Catholic Church, and the Ecclesiastical Committee of the Assembly began considering the matter as early as August 1789. This Committee was strengthened in February 1790 by patriotic priests due to rising tensions within its ranks.

From April onwards, discussions centered on a proposal by Martineau, a Gallican Catholic, who sought to clarify the procedures for appointing priests and to eliminate privileges, particularly those stemming from Rome. The nation was to compensate clergy members. This raised the issue of the Pope, who was not consulted, intensifying tensions.

Despite these challenges, the proposal was passed on July 12, 1790, without significant difficulty, and the king accepted it on July 22. However, this did not quell the tensions—quite the opposite. Protests mainly came from bishops, who wanted to appeal to the Pope (who condemned the Constitution in March 1791) and called for a national council, a demand Robespierre rejected. But it was the constitutional oath that truly ignited the situation.

Constitutional Oath and the Explosion

The constitutional oath was a logical follow-up to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. It responded to the bishops’ refusal to implement the Constitution. On November 27, 1790, it was decided that public clergy officials were required to swear loyalty to the Nation, the Law, the King, and the Constitution. In the Assembly, only seven bishops, following Grégoire’s lead, took the oath. The Assembly members were surprised by the lack of adherence. By 1791, just over 50% of the clergy had taken the oath, with significant regional disparities.

This schism within the Church in France led to clashes and violence at the local level, directed at both constitutional clergy and those who resisted the oath, despite the Assembly’s efforts to enforce religious freedom while imposing the constitutional Church. Punitive expeditions, collective humiliations, and even stoning became common practices, not only among the Sans-Culottes.

On November 29, 1791, the activist refractory clergy were labeled “suspected of sedition”; on May 27, 1792, they became eligible for deportation. The fall of Louis XVI on August 10, 1792, triggered a large emigration of refractory clergy.

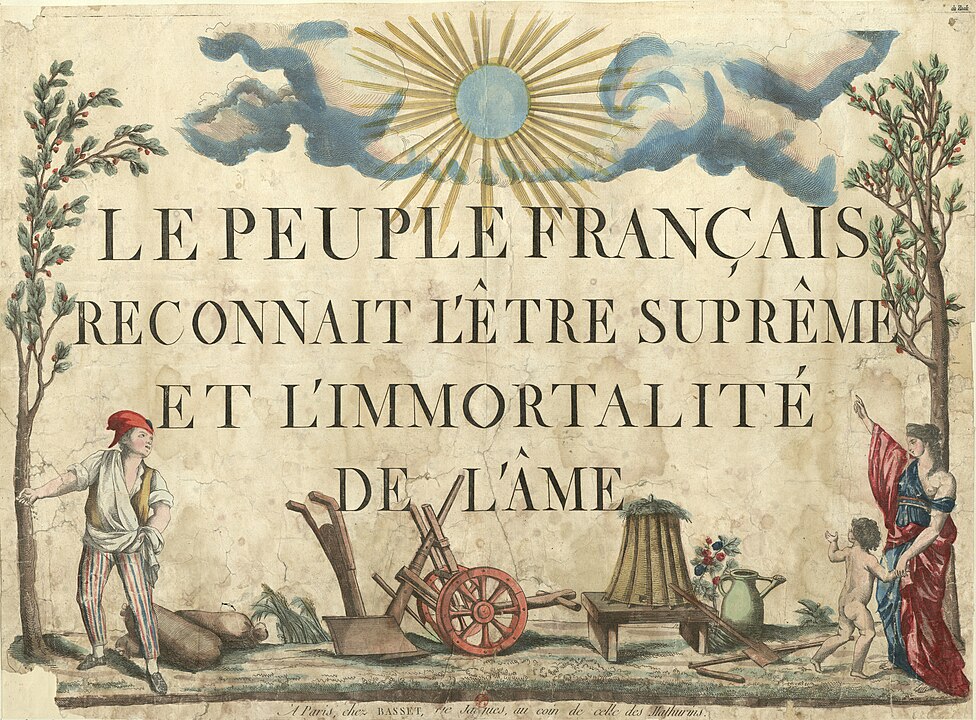

Dechristianization

Amid the growing tensions surrounding the Church, and localized violence (in the South) involving Protestants, there was a parallel rise in anticlericalism. The year 1793 marked the beginning of a period during which the rejection of Christianity was neither a spontaneous revolt nor a directive of the revolutionary government.

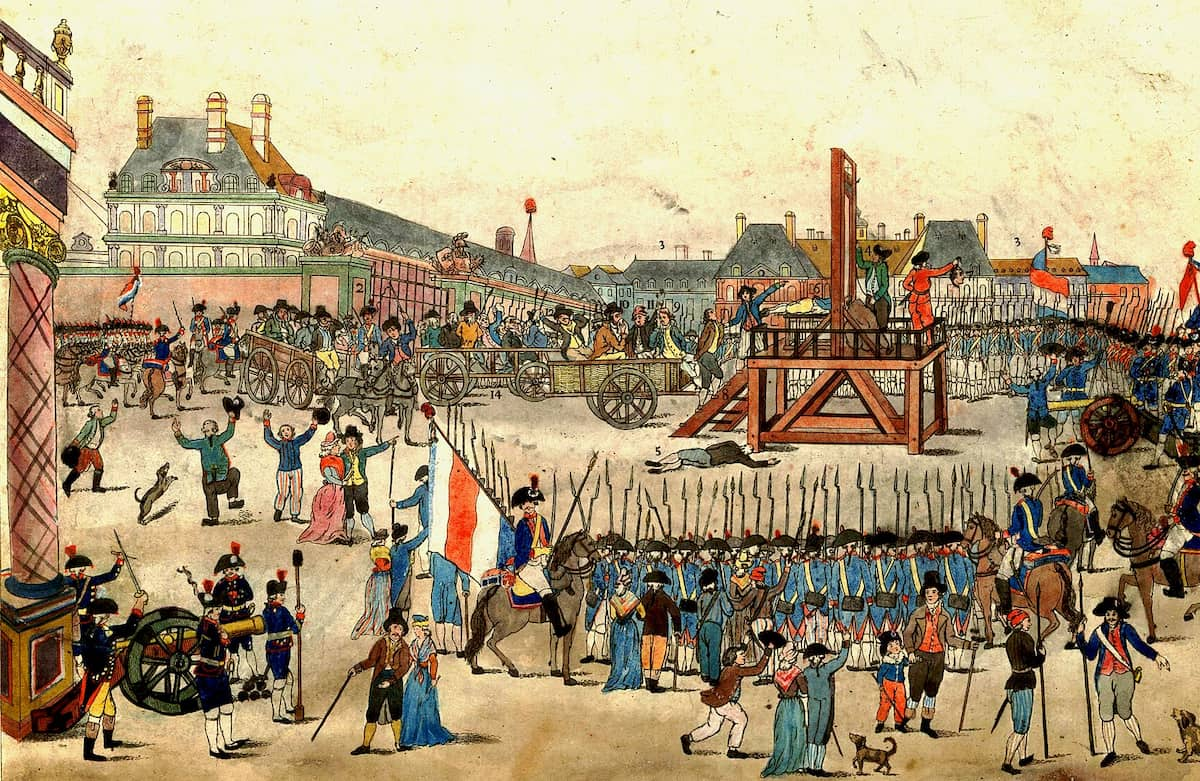

The phenomenon had been present in revolutionary celebrations since the Federation Festival on July 14, 1790. In the same spirit, the Festival of Regeneration, or Unity and Indivisibility of the French, held on August 10, 1793, was a fully secularized ceremony marking a key moment. However, the offensive occurred during the winter of the same year, initiated by politically active circles.

This period saw rural communities renouncing religious worship, or antireligious demonstrations, led by figures such as Fouché in Nièvre. Elsewhere, churches were transformed into Temples of Reason (as happened to Notre-Dame on November 10, 1793), priests were married, and religious books were burned in public displays. The most affected regions were the Paris area, the Center, the North, parts of the Rhône Valley, and Languedoc.

In a less radical move, on October 5, 1793, the Convention abandoned the Gregorian calendar for the Republican calendar.

This dechristianization movement shocked even the Committee of Public Safety, and Robespierre, in a speech on November 21, 1793, harshly criticized “aristocratic atheism.” Following his lead, the Convention condemned “all violence and measures against religion.” Nevertheless, dechristianization continued in rural areas until the spring of 1794.

The end of the dechristianization period saw the rise of Robespierre’s deist influence and the emergence of the Cult of the Supreme Being, following other revolutionary cults. The year 1795 also witnessed the first law separating Church and State.