The clothing of ancient Egypt concerned the relationship of its people with their clothes, footwear, jewelry, and cosmetics. Despite being known for its multidisciplinary knowledge, Egypt is also responsible for introducing fashion and beauty ideas to the rest of the world. The ancient Egyptians placed great importance on hygiene and self-care; mirrors, combs, and bathing objects were some of the most used items. Egypt also has a long tradition of textile production dating back to the first millennium BCE.

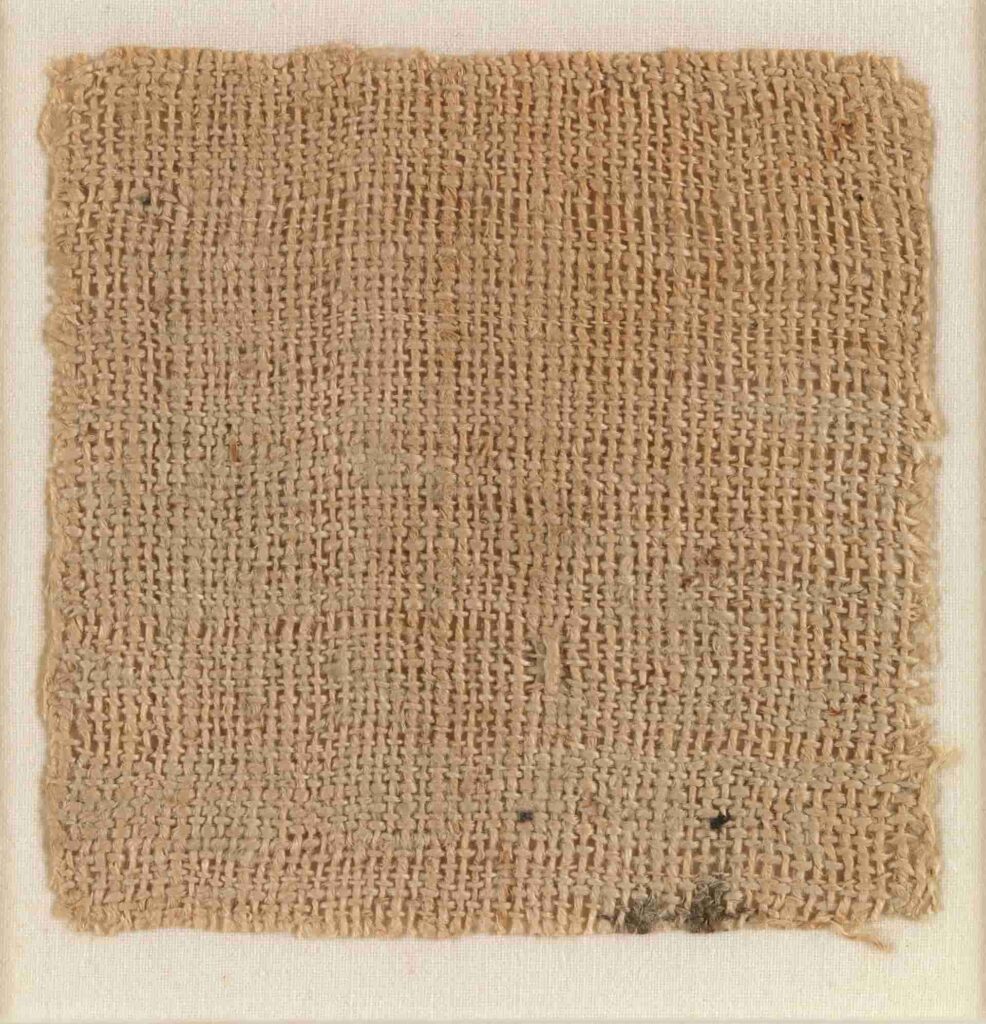

Thanks to the dry climate of the territory, much of its fabric has survived until the 21st century, and clothing still influences various contemporary nations. Consequently, the British Museum holds a collection of about five hundred textile pieces dating from the first millennium CE. Linen stands out as the main raw material used in clothing. Egyptian clothing has become one of the main influences in the textile industry, inspiring various fashion collections by modern brands such as Balmain, Valentino, Givenchy, and Chanel.

The Ideal of Beauty

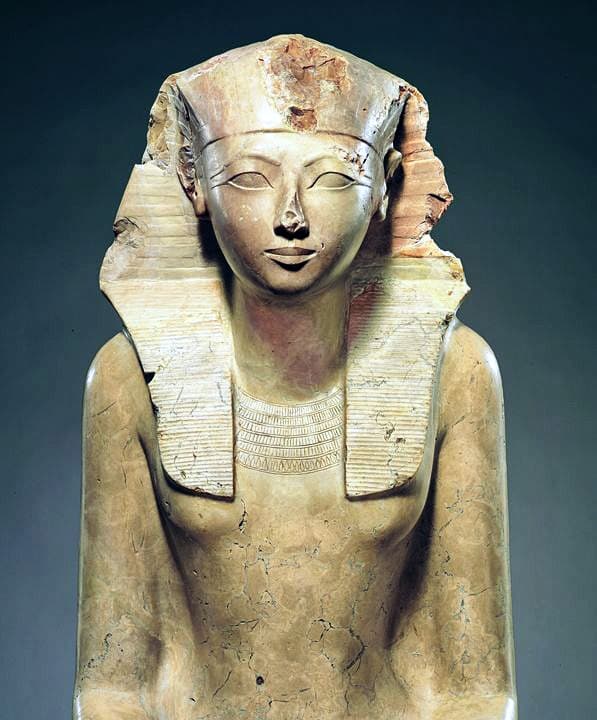

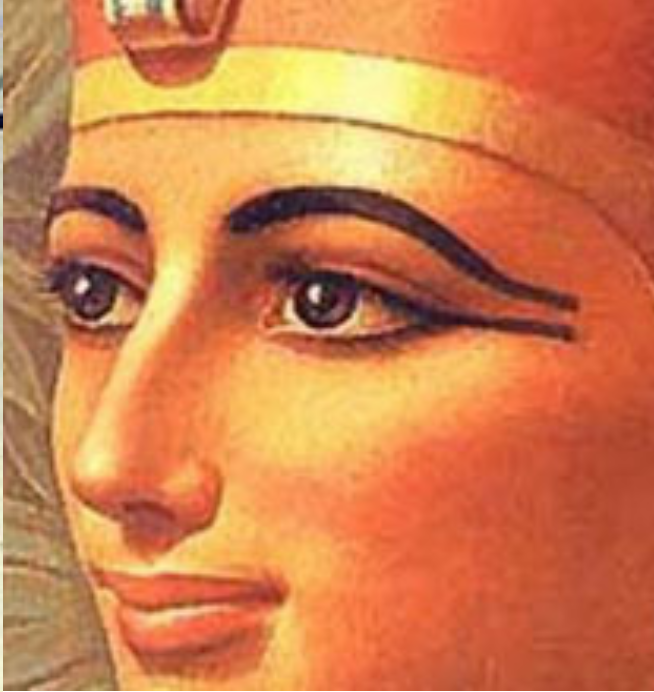

The extant monuments of ancient Egyptian art give a clear idea of how representatives of various classes looked and dressed. For both men and women, tall, slender figures with a thin waist and broad shoulders, almond-shaped eyes, thin facial features, a straight nose, and full lips were considered ideal. Women were expected to be fair-skinned, have small breasts, wide (but not curvy) hips, and long legs. The modern archaeologist Leonard Cottrell wrote about the ancient Egyptian beauties:

“How happy the ladies of Egypt would be if they knew that even after 5,000 years they could be admired! (…) The beauties of Greece and Rome delight us, but do not excite us. They seem as cold as the marble from which they are sculpted. But if you put a Dior dress on Nefertiti and she enters a fashionable restaurant in it, she will be greeted with admiring glances from those present. Even her cosmetics won’t cause gossip.”

Fabrics in Ancient Egypt

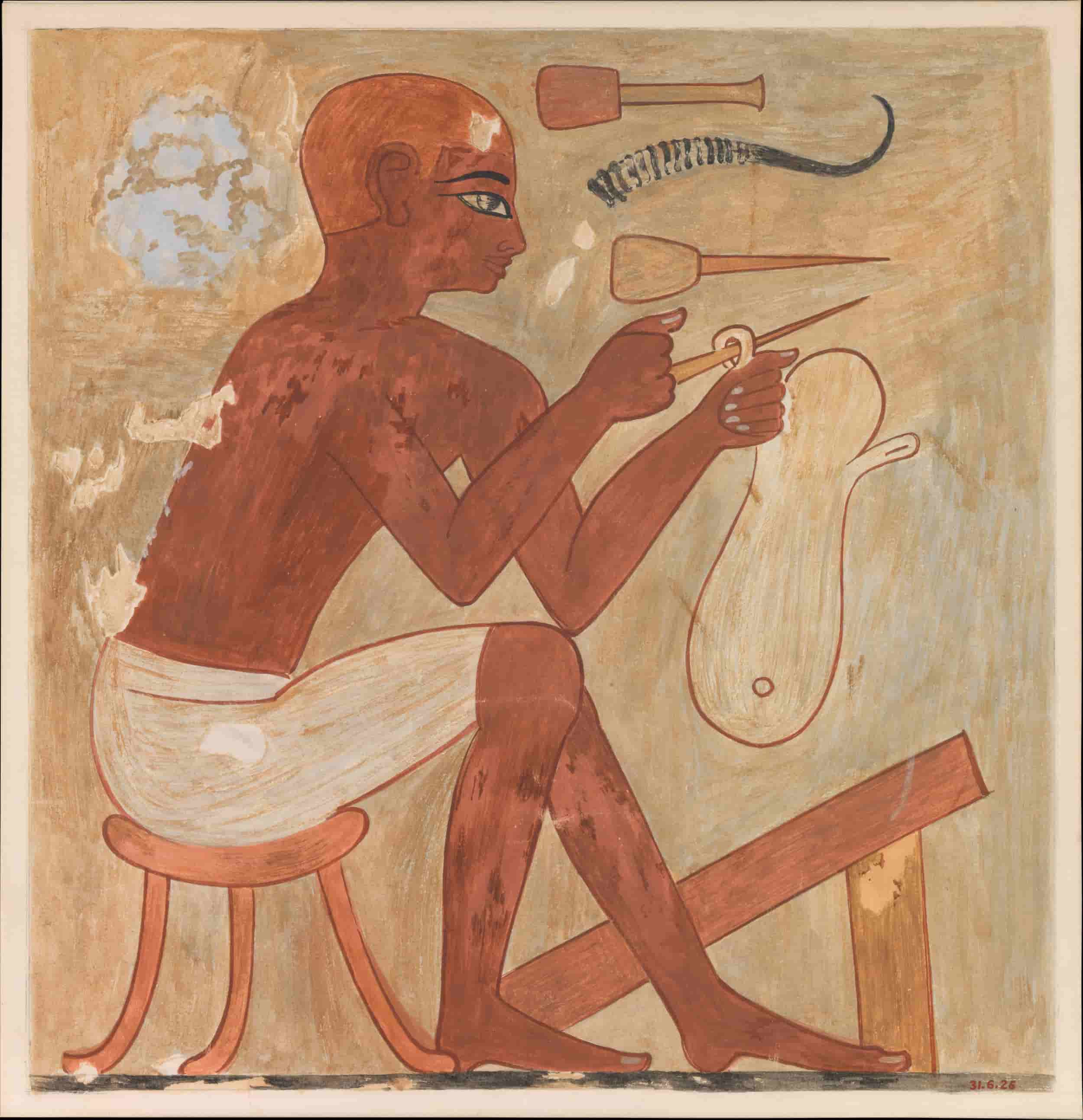

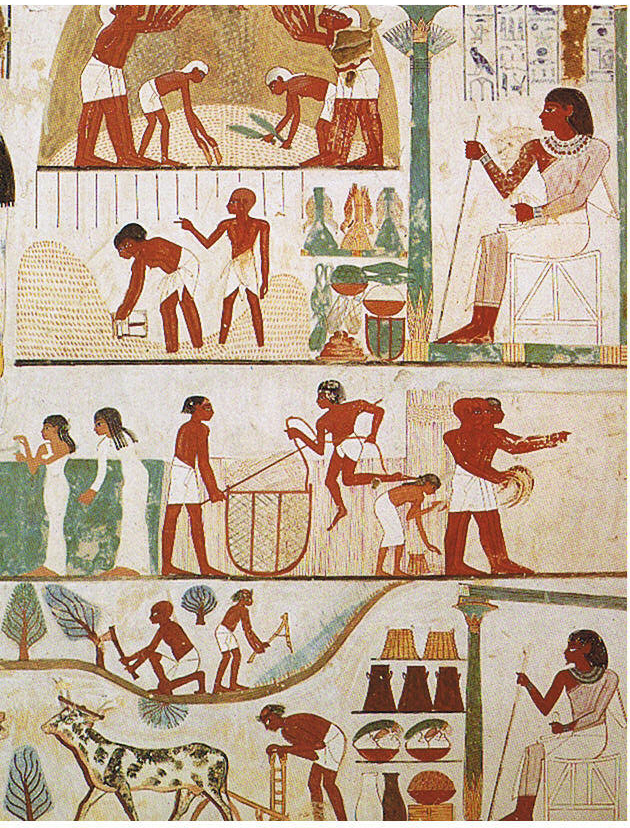

Although sheep farming has been practiced in the Nile Valley since ancient times, wool was considered ritually impure. Only linen fabrics were used for making clothes. Both men and women could weave cloth, but spinning was exclusively a women’s task; judging by surviving images, particularly skilled craftswomen could spin with two spindles simultaneously, which undoubtedly required special coordination of movements.

The skill of ancient Egyptian spinners and weavers is still impressive to this day. Samples of fabrics have been preserved, in which 84 warp threads and 60 weft threads per square centimeter were present; 240 meters of such thread weighed only 1 gram. The lightest, almost transparent fabrics, made by Egyptian masters from such threads, were compared to “a baby’s breath” or “woven air” and were literally valued as much as gold.

Ancient Egyptian fabrics were dyed in various colors, most often red, green, and blue; in the New Kingdom era (1580–1090 BC), yellow and brown dyes appeared. The fabrics were not dyed black. Blue clothing was considered mourning attire. But the most common and beloved color among all layers of society was white.

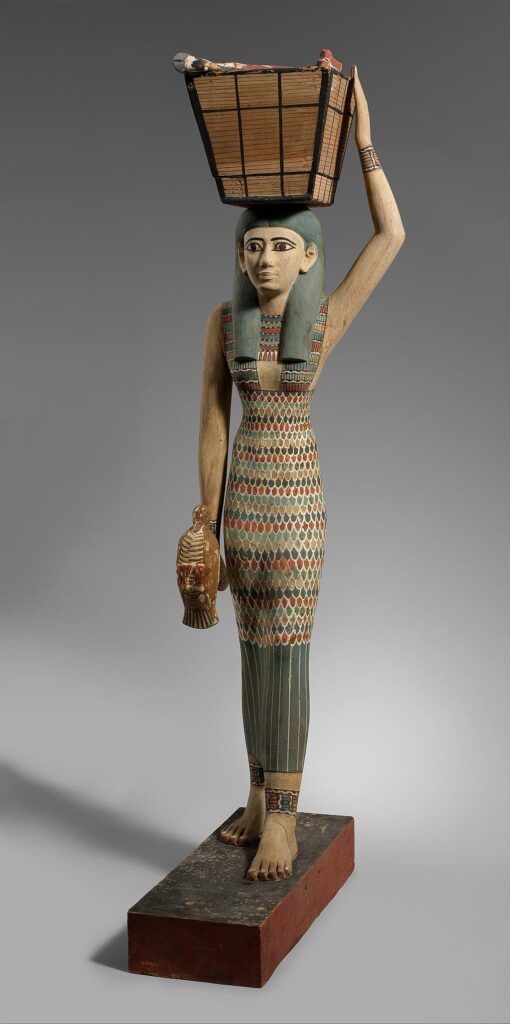

Fabrics could be plain or patterned. Feather motifs (symbolizing the goddess Isis) and lotus flowers were favorite ornamental motifs. The pattern was applied to the fabric using embroidery or a special dyeing method using various mordants. The deities associated with weaving and clothing were Heket-hetep and Taet.

Aspects of Clothing

Egyptian clothing was simple and practical, and for the vast majority of the population, the same garment worn by a woman could be worn by a man. Social dignity was not based on gender but on social status. This means that men and women occupied the same spaces and were seen as equals. For this reason, the aesthetic sense of clothing was almost unisex long before this concept was understood by the world, permeating its vocabulary.

Throughout the history of Ancient Egypt, clothing already indicated the individual’s position in the social stratum. The higher one’s position in society, the greater the quantity and quality of fabrics and adornments worn. To demonstrate their status, prestige, vitality, and strength, pharaohs used pleats in clothing, jewelry, makeup, and body essences, which were used as perfume.

The people were very meticulous about their cleanliness and appearance; careless individuals were considered inferior. Over approximately 3000 years, Egyptian clothing remained traditional. However, with the invasion of new peoples into their territory, influences of new customs, especially from the Roman Empire, were generated.

Early Dynastic Period and the Old Kingdom

During the Thinite Period (or Early Dynastic Period), men and women from the lower classes dressed similarly, wearing plain loincloths, probably white or light-colored, reaching the knee. These were mainly made of linen, cotton, or papyrus reed. Before the development of linen, people wore clothes made of leather or woven papyrus.

Egyptians from the upper class of the same period did not differ much from the standard, except for greater ornamentation. The aristocracy was distinguished from farmers and artisans mainly by the jewelry they wore.

Children of both sexes did not wear clothes from birth until puberty.

Shepherds, boatmen, and fishermen mainly lived with a simple leather loincloth from which hung a curtain of reeds; many also worked completely naked, at least until the Middle Kingdom; by this time, it became rare to see a naked worker. Female millers, bakers, and harvest workers are often depicted with a long wraparound skirt but with the upper body exposed. Washers and laundresses who worked daily on the banks of the Nile washing other people’s clothes performed their tasks naked because they were in the water for a long time.

Shendyt

The Shendyt was one of the most common garments in Ancient Egypt. It was a kind of short skirt made of a rectangular piece of linen wrapped around the body and tied at the waist with a fabric belt. The Shendyt was regularly worn by men of the working class.

Men from the upper classes preferred more elaborate Shendyt with embroidered details, gemstones attached to the clothes, and accessories. Peasant men wore Shendyt from the waist to the knees without covering the upper body.

Kalasiris

Women’s clothing was more distinct among the classes; women of high society wore long dresses fitted to the body, which could have sleeves or not. These dresses were called Kalasiris; they were supported by straps on the shoulders and sometimes complemented with a transparent tunic worn over them. Over the dress, women could choose to wear shawls, capes, or robes. The shawl was a piece of fine linen fabric about 1.2m wide by approximately 4m long.

Fashion for women showing their breasts was not a concern. The dresses of high-class women sometimes started below the breasts and went down to the ankles.

Middle Kingdom

The First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) of Egypt began shortly after the collapse of the Old Kingdom, resulting in drastic changes in Egyptian culture, but clothing remained relatively the same. It was only in the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) that changes in the Egyptian way of dressing were seen.

The dresses of aristocratic women changed, as they are now often made of cotton. The dresses, still tight-fitting, now had sleeves and presented a deep neckline adorned with a necklace closure at the neck. They were also made of a single piece of fabric in which the woman would wrap herself, adding a belt, thus transforming the top of the dress into a blouse.

However, there is evidence of high-class women wearing dresses that went from the ankles to the waist and were supported by thin straps that covered the breasts, passed over the shoulders, and ended at the back.

Men of the period continued to wear simple Shendyt with pleats at the front. It is not known exactly how the ancient Egyptians pleated their clothes, but images from the arts clearly show pleats in both male and female clothing. The most popular piece of clothing among men of the upper class was the triangular apron; a starched and ornamented Shendyt that fell just above the knees and was secured by a belt. It was worn over a loincloth, which was a triangular strip of fabric passing between the legs and tied at the hips.

The New Kingdom

Shortly after the Middle Kingdom, Egypt entered the Second Intermediate Period (1782 – 1570 BCE), during which the foreign people known as the Hyksos ruled Lower Egypt. Meanwhile, the Nubians seized control of the southern borders of Upper Egypt, leaving only Thebes in the hands of the Egyptians.

The Hyksos brought many advances, innovations, and inventions to Egypt that later proved to be of great utility, but they did not seem to influence Egyptian fashion. This was mainly because the Hyksos greatly admired Egyptian culture and emulated Egyptian beliefs, behavior, and clothing in their cities.

In 1570 BCE, the Theban prince Ahmose I (1570-1544 BCE) expelled the Hyksos from the country and initiated the period called the New Kingdom of Egypt (1570-1069 BCE). It was during this era that the greatest advances in Egyptian fashion occurred. The styles of the New Kingdom are those most portrayed in movies and television, regardless of the period they depict.

The New Kingdom was the Egyptian era when the territory entered the international scene, and ties with other nations were stronger than ever.

Clothing became more elaborate; the wife of Ahmose I, Ahmose-Nefertari, is depicted in a dress that reaches to the region of her ankles, also featuring winged sleeves and a wide collar.

Kalasiris adorned with jewelry began to appear at the end of the Middle Kingdom but only became more common among the upper classes in the New Kingdom. Wigs adorned with beads and jewels also appeared more frequently during this time.

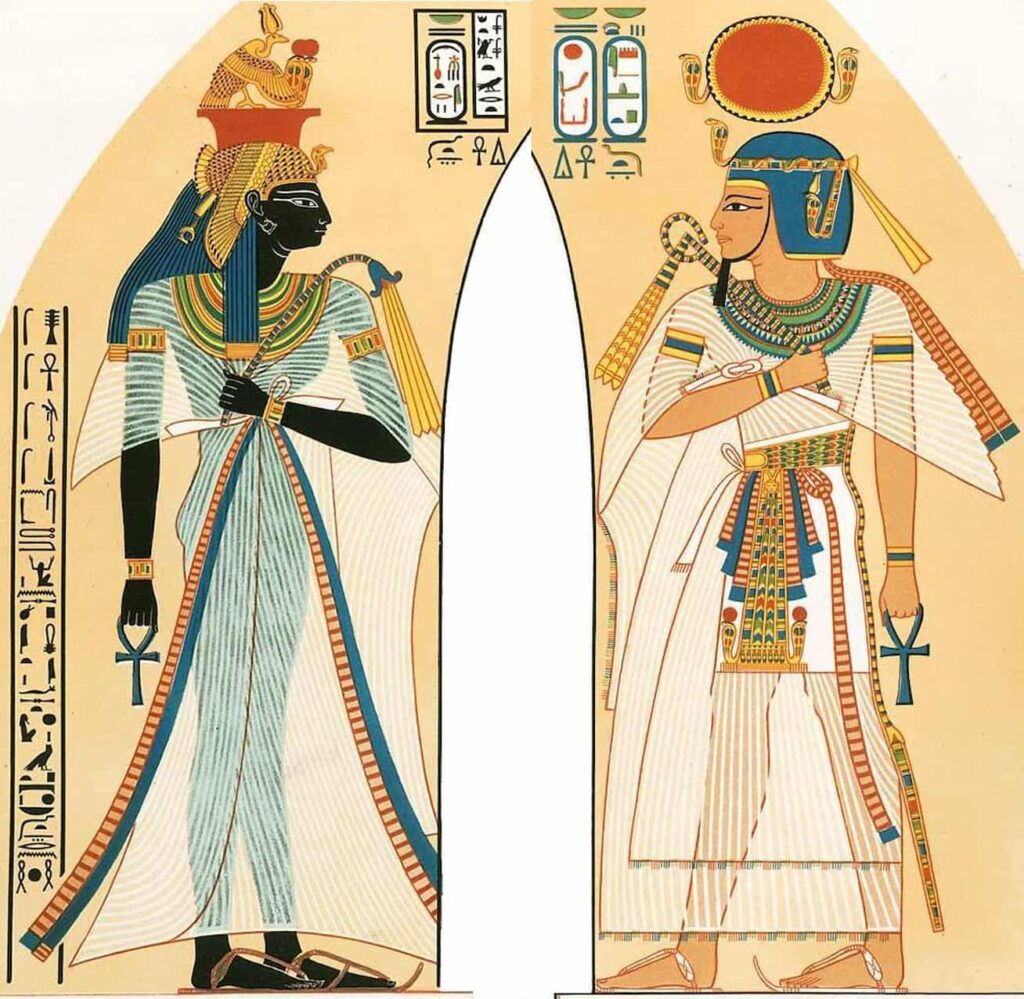

The fashion innovation of the New Kingdom was the linen capelet. The capelet, or shawl cape, consisted of a rectangular piece of linen that was twisted, folded, or cut and often attached to a highly ornamented collar. Very similar to a poncho, it was widely used as an overlay to the Kalasiris, which started at the waist or just below the breasts, thus becoming the most popular style among the ruling classes.

Men’s clothing also advanced rapidly in the New Kingdom. The Shendyt of this period extended past the knee line, were intricately embroidered, and were usually complemented by a lightweight, loose blouse. The Pharaoh, depicted with his Nemes headgear, is regularly seen in this type of attire, also wearing sandals or slippers. Especially notable is the use of Shendyt and blouses with pleated and more elaborate sleeves. Large swaths of fabric were worn hanging from the waist, and intricate folds were visible beneath the sheer skirts. This style is also popular among royalty and the aristocracy, who could afford the material.

The lower classes continued to wear simple Shendyt, both sexes, but now more working-class women appeared with their upper bodies covered. Previously, Egyptian servants were depicted in tomb paintings as either fully or partially naked. However, in the New Kingdom, a large number of servants are represented, not only fully covered but also in slightly more elaborate dresses.

The clothes worn by the servants of officials and people in important positions were more refined than those of the common people. A servant depicted in a tomb from the eighteenth dynasty wears a finely pleated linen tunic and a loincloth with a wide and also pleated sash.

Undergarments

Undergarments were also developed during this period, evolving from the rough triangular piece of cloth wrapped around the waist and between the legs to a finer piece of cloth sewn to the ideal size of the wearer or tied at the hips.

The fashion of high-class men in the New Kingdom was to wear this undergarment beneath a loincloth over which a long, transparent blouse was worn, falling to the knees, with a wide collar – for the nobles – along with bracelets and sandals.

Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BCE) was buried with over 100 undergarments of this type, as well as shirts, jackets, Shendyt, and mantles. This was one of the most accurate examples of New Kingdom attire ever found.

Footwear

Although it was customary to walk barefoot, it was in this territory that the first sandals appeared due to the climate and sandy geography. The material of Egyptian sandals was mainly leather, woven straw, strips of palm leaves or papyrus, or even swamp reeds.

It is noted that footwear held a certain importance in Egyptian society, as there are drawings of King Narmer, dating back to 3100 BCE, showing a servant who had the function of “sandals carrier,” meaning he walked behind the kings carrying their royal footwear wherever they went. The Pharaohs wore very simple sandals, but they were adorned with gold. Although sandal bearers and people of lower classes were often depicted barefoot in paintings, they also wore sandals, as it was a luxury item for all.

These objects achieved a social function; when a pharaoh entered a temple or his subjects celebrated death in funeral chapels, they removed their sandals at the sanctuary’s entrance. There is a strong relationship between shoes and the sacred, a relationship that has been portrayed in passages of the Bible and is also common among Muslims when entering mosques.

For a long time, the only type of footwear for the ancient Egyptians was sandals. Very simple in shape, they consisted only of a sole (sometimes with an upturned toe), to which two straps were attached: one strap began at the thumb and connected to the other, covering the instep of the foot, thanks to which the shoe resembled a stirrup. Sandals were usually made of leather or papyrus leaves.

Archaeologists have repeatedly found golden sandals in royal tombs, but it is not yet clear whether such shoes were used during the lifetime of their owners, or whether they were only an accessory of the funeral rite, a kind of ancient Egyptian analogue of “white slippers”.

During the New Kingdom period, other styles of shoes appeared. In one of the chests found by researchers in the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62), among other things, there were slippers without heels and leather socks embroidered with small gold sequins. Also found in the tomb were Tutankhamun’s sandals, depicting nine bows (the main enemies of Egypt), which the pharaoh symbolically “tramples on, tramples underfoot.”

Despite the fact that the shoes were so simple, the Egyptians took great care of them. Peasants, going to the city on business, often carried their sandals in their hands and put on shoes only on the spot. Nobles also often walked barefoot, especially at home.

Funerary Sandals

The Egyptians believed that at the moment of death, some objects that could facilitate the transition to the afterlife were buried with the deceased. This custom was common both to peasants and to pharaohs. One of these objects is the sandal, which resembles those worn in life. In funerary rituals, the footwear could be made of leather or papyrus, but if made for a member of royalty, gold was used as the raw material.

Gold sandals are not suitable for daily use; however, it was believed that earthly concerns ceased at the moment of entry into the afterlife. Texts from the Pyramid Age refer to the desire of the dead “to walk in white sandals along the beautiful paths of paradise where the blessed wander.”

Haircuts

Men and women in Egypt regularly shaved their heads to protect themselves from lice and reduce the time it would take to have a head full of hair. In the Old Kingdom and the First Intermediate Period, women are depicted with hair length just below the ears, while in the Middle Kingdom, hair is worn to the shoulders. Children also had shaved heads, except for one or two locks or a braid on the side of the head. This hairstyle was called a sidelock, a style worn by the god Horus as a child.

Characterized by strictness and precision in lines, all ancient Egyptian hairstyles received the name “geometric.” Due to the hot climate, most Egyptians wore simple hairstyles with short-cropped hair.

Often, Egyptians shaved body hair for hygiene reasons. This was especially true for priests, whose status required constant cleanliness. According to Herodotus:

“in other countries, the priests of the gods wear long hair, but in Egypt they are shaved… every three days, the priests shave the hair on their bodies so that they do not get lice or other parasites during worship.”

All the free people in Egypt wore wigs. Their shape, size, and material indicated the social status of the owners. Wigs were made from natural hair, animal wool, plant fibers, and even ropes. They were dyed in dark tones, with dark brown and black considered the most fashionable colors.

The red hair of the mummy of Ramses II is dyed with henna.

Judging by the surviving images, there were many wig styles known. They often reached the shoulders, but on ceremonial occasions, long wigs with large parallel curls were worn. Hairstyles were heavily perfumed with fragrant oils, essences, and sticky compositions. In images, the heads of noble Egyptians and their spouses are often crowned with small, whitish cones, likely made of wax or solid fat mixed with perfumes. During festivals or feasts, the cone gradually melted, giving the hair of its owner an exquisite aroma.

Women’s hairstyles were significantly longer and more elaborate than men’s throughout all periods. Ancient Egyptian aristocratic women, like their husbands, often shaved their heads and wore wigs. The most typical wig hairstyles included two: the first—all the hair was divided by a longitudinal parting, closely fitting the face on both sides, and trimmed evenly at the ends; the top of the wig was flat. The second hairstyle had the shape of a sphere. Over time, a large curled wig became popular, with three strands falling on the chest and back.

Hairstyles were also made from one’s own hair, freely spreading them down the back and decorating the ends with tassels or aromatic resin balls. Often, the hair was curled in ringlets; this curling was done after combing small, thin braids. The cold setting was widely used for curling (for this, strands of hair were wound on wooden sticks and covered with mud, and when it dried, it was shaken off, and the hair was combed). Lucas A., after studying wigs, discovered beeswax, which he considers a suitable material for curling.

Medical papyri contain recipes for wrinkles and baldness (Ebers Papyrus, Edwin Smith Papyrus).

Children—boys and girls—had their hair shaved, leaving one or several strands (for girls—on the crown, for boys—on the sides of the head). These strands were twisted into a lock (such a hairstyle was called the “lock of youth”) or braided into a braid on the left temple.

Wigs

The Egyptian elite took great care of their hair. Hair was washed, perfumed, and sometimes dyed with henna. Both men and women wore hairpieces, but wigs were more common. Wigs were made of human hair and had a filling of vegetable fiber at the bottom. They were also used to protect the scalp.

The wigs of the New Kingdom are the most ornate, especially for women, featuring pleated hairstyles with bangs and layers reaching shoulder-length or below. Hair was arranged in braids and strands; they were usually long and heavy.

They may have been mainly worn on festive and ceremonial occasions, like in 18th-century Europe. Priests shaved their heads and bodies to affirm their devotion to the deities and reinforce their cleanliness, a sign of purification.

Moustache

The fashion for moustaches and beards changed from century to century, giving way in general to clean-shaven faces. Such a fashion can be judged by the preserved sculptural portraits (for example, of Rahotep and Pharaoh Menkaure) and funerary masks. At the same time, it was forbidden to shave during the mourning period.

The false cylindrical beard of the pharaoh was one of the royal regalia, symbolizing masculinity and strength. Like a wig, it was made of wool or cut hair, twisted with gold threads, and tied to the chin with lace. This ceremonial beard could be shaped in many ways, but the most common was a pigtail curled at the end, similar to a cat’s tail.

Headgear

Because most Egyptians wore wigs, their headgear was quite simple. Slaves and peasants, working in the fields, covered their heads with kerchiefs or small cloth caps. Noble people wore such caps, embroidered with beads, under their wigs.

The most popular headgear for representatives of all classes was a headscarf (called a khepresh or nemes). It was tied over the wig in such a way that the ears remained uncovered. Two ends of the scarf hung down the chest, the third down the back (sometimes it was fastened with a ribbon or a hoop). The headscarf could be white or striped, and the color of the stripes depended on the status and occupation of the owner; for example, warriors had red stripes, priests had yellow ones, and so on. A headscarf with blue longitudinal stripes could only be worn by the pharaoh. It was called a khepresh-ushebti and was usually supplemented with a metal hoop with the uraeus or a ribbon. However, during various ceremonies, the pharaoh wore a crown—more precisely, that variation of it prescribed by the court ceremonial for the occasion.

The following types of crowns were known: 1) the white crown of Upper Egypt (hedjet), resembling in shape a cone or a bottle; 2) the red crown of Lower Egypt (desheret), which represented a truncated inverted cone with a flat bottom and a high raised rear part; 3) the double crown (pschent), combining the first two and symbolizing the unity of the country; 4) the “battle crown” blue with red ribbons; 5) the “crown of Amun” of two feathers with a gold disk between them; 6) the atef crown— a double crown, appeared after the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt (4th millennium BCE); 7) the “reed crown” (hemhemet)— a complex structure of gold feathers, ram’s horns, snakes, sun disks, etc. Judging by the surviving sculptures and reliefs, there were up to 20 types of crowns (no authentic ancient Egyptian crown has survived to our time).

An obligatory attribute of any royal headgear was the uraeus—a golden image of a cobra, which was a symbol of the goddess Wadjet, the patroness of Lower Egypt. It was placed above the forehead and sometimes supplemented with the golden head of a vulture—a sign of Nekhbet, the goddess of Upper Egypt.

Priests in temples during rituals wore gypsum-painted masks depicting gods. For example, priests of the god Thoth wore masks in the form of the head of the sacred ibis bird, and priests of Anubis wore masks in the form of the head of a jackal, and so on.

For women, the most common headgear was ribbons and diadems, plain or ornamented. The wives of pharaohs are often depicted wearing a crown resembling a vulture with outspread wings, made of gold with an inlay of precious stones or colored enamel. Sometimes, tall gold feathers—shuti (the attribute of the goddess of truth, Maat)—and an image of the lunar disk—the sign of Hathor, the goddess of beauty and love—were placed on top of this crown. Such headgear, of course, was intended only for special occasions. Generally, it seems that the headgear of queens was not so strictly defined by palace ritual and more reflected their personal tastes. For example, the beautiful Nefertiti preferred a simple blue cylindrical crown, which emphasized the graceful head carriage and slender neck.

Ceremonial headgear could be the same for men and women. In the New Kingdom era, the atef became the main crown of the queens of Egypt.

Makeup and Accessories

Men and women of the elite took care of their appearance with various cosmetics, using oils, perfumes, and paints for the eyes and face. Most often, they wore eye makeup that lined the eyelids with a line of black Kohl, an ancient cosmetic that has a similar effect to charcoal in paintings. Just like in the 21st century, they had the help of mirrors when applying makeup.

Makeup not only had an aesthetic function but also served as protection for the skin against adverse atmospheric conditions. Egyptians also wore makeup for medical reasons, as kohl and other cosmetics offered immunity against a range of diseases. Moreover, traditional Egyptian beliefs stated that if a mother wore eye makeup on her children, she would be protecting them from the evil eye.

The Egyptians used mineral pigments to produce makeup. Galena and malachite were ground on stone palettes to make eye paint, applied with fingers or a Kohl pencil made of wood, ivory, or stone. The eye paint enhanced the eyes and protected them from the strong sunlight.

During the Old Kingdom, green malachite powder was applied under the eyes. They applied oils and fats to the face to protect it, mixed them into perfumes, and placed them in incense cones worn on the head, which were worn by both men and women. The cones were made of tallow and fat that gradually melted, releasing the fragrance. However, no specimens of these perfumed cones have been found.

Accessories

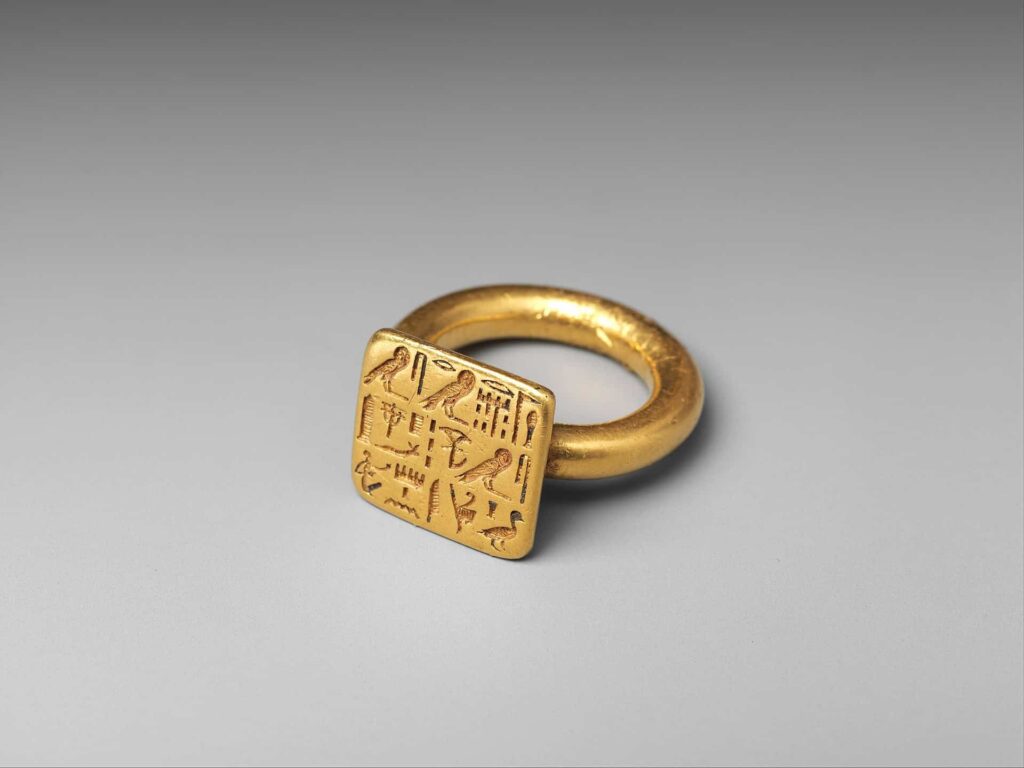

From ancient times, jewelry was worn by the elite as adornment and as an indication of their status. Bracelets, rings, earrings, necklaces, pins, belt buckles, and amulets were made of gold and silver and inset with precious stones like lapis lazuli, turquoise, carnelian, and amethyst. Faience and glass were also used to decorate jewelry pieces.

The elegant design of Egyptian jewelry often reflected religious themes. Pieces included images of gods and goddesses, hieroglyphic symbols, birds, animals, and insects that played a role in the creation myth. The most common symbols are the scarab beetle, the eye of Horus, lotus and papyrus flowers, the vulture and the falcon, and the snake. Symbols such as the Isis knot, the shen ring, a symbol of eternity, and the ankh, a symbol of life, can also be mentioned.

A person’s jewelry was placed in their tomb to be worn in the afterlife, along with many other personal items, such as the sandal mentioned earlier. The costume of the ancient Egyptians consisted of a small number of elements, thanks to which accessories acquired special importance. They, along with jewelry, served as the main carriers of information about the social status of their owner.

The most common of the accessories was a belt. Commoners were girded with narrow leather straps; wealthy people, on the other hand, wore long woven ribbon belts (most often red or blue, sometimes patterned). On solemn occasions, the king wore a gold belt over the cloth belt. In front of it was attached a ceremonial apron made of gold plates, connected by strips of beads and decorated with colored glass. At the bottom, it was trimmed with a fringe of small gold uraeus.

A tail was hung from the back of the royal belt with the help of a special hollow cylinder. Originally, it was the most natural oxtail, which corresponded to one of the pharaoh’s titles, “Mighty Bull of the Two Lands”; over time, the real tail was replaced by a bundle of beads (two such ritual tails were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb).

The ancient Egyptians were familiar with gloves and mittens. Mittens were made of linen and were used to protect the hands from calluses and injuries when shooting a bow or driving a chariot. Gloves (cloth or leather) apparently had a ceremonial purpose.

Materials

For making jewelry, gold was most commonly used, the rich deposits of which were discovered in Egypt in ancient times. Moreover, what was valued most was not so much the material’s cost as its picturesque properties. Egyptian craftsmen could use various additives to give gold diverse shades—from white to green. In jewelry, gold was always combined with colored enamels and inserts of gemstones and enamel. Electrum, an alloy of gold and silver, was also widely used; it was used to make everyday items as well as fastenings and connecting elements in bracelets and necklaces.

Silver was rare and was exported from Asia, which is why it was valued more than gold for a long time. In the eastern desert, bright semi-precious stones were mined (carnelian, amethyst, and jade), and turquoise was mined in Sinai. Lapis lazuli of deep blue color reached Egypt from the territory of modern-day Afghanistan. Glass and faience (glaze based on stone or sand) often replaced stones since they could be colored in various hues. The gemstones we now consider precious—rubies, sapphires, diamonds, and emeralds—were unknown to the ancient Egyptians. Ancient Egyptians were not familiar with diamonds, opals, rubies, and sapphires; regarding emeralds, researchers’ opinions differ because emeralds are difficult to distinguish from beryl and green feldspar.

The most common among all types of jewelry were various necklaces, especially the so-called usekh—a large necklace made of several rows of beads, symbolizing the sun. It was made in the form of an open circle, with ties or clasps at the back. The beads in the bottom row most often had a drop shape, while the rest were round or oval. Often, the beads were interspersed with goldfish, shells, and scarabs. Often, such a necklace was so wide that it completely covered the shoulders and upper part of the chest and was very heavy—a royal gold necklace could weigh several kilograms. To make it lay beautifully, it was usually mounted on a lining of leather or fabric, turning it into a kind of collar. Necklaces were not only part of the attire; they also served as badges of honor. Pharaohs awarded distinguished warriors and officials with golden necklaces.

In addition to necklaces, bracelets were beloved adornments for both men and women, worn on the arms (on the forearms and wrists) and ankles. Bracelets could be very diverse—in the form of two embossed plates connected by clasps, massive gold rings with beads, gold cords, or ribbons. Rings with inserts of semi-precious stones were also worn. Signet rings with the names of the owners engraved on them and images of gods were in vogue. Hoop earrings (with or without them) were extremely popular. Sometimes they were so large and heavy that they deformed the earlobes.

Of course, only the wealthy could adorn themselves with gold and gemstones. But people of modest means loved jewelry no less. Their adornments were usually made of relatively inexpensive materials—ceramics, glass, bones, etc. However, in terms of beauty and elegance, they sometimes rivaled jewelry. For example, faience beads for necklaces were shaped like lotus buds and petals, cornflowers, daisies, grape clusters, leaves, etc., and were painted in different colors. Various shades of blue and green, as well as white, were most commonly used. Such necklaces, presumably, looked very beautiful on tanned skin.

Ancient Egyptians willingly used live flowers as adornments, making bouquets, wreaths, and garlands out of them. They especially loved white, blue, and pink lotuses. Egyptian ladies inserted lotus flowers into their hairstyles so that they hung over their foreheads, inhaling their fragrance.

Ancient Egyptian jewelry served simultaneously as amulets, intended to protect against diseases and the evil eye, ward off evil spirits, etc. The “Eye of Horus” udjat (a symbol of the solar deity), the “ankh”—a cross with a loop at the top, denoting life—as well as the figure of the scarab beetle (a symbol of resurrection, peace, and the sun), were believed to possess the greatest magical power. The udjat eye amulet was placed between the burial shrouds of the mummy and the scarab amulet—on the heart of the mummy.

Cosmetics and Perfumery

The use of cosmetics by ancient Egyptians can be traced back to the predynastic period, although there’s no evidence of a profession like cosmetology in ancient Egypt based on known findings. Scenes of preparing perfumes, applying cosmetics, and numerous cosmetic items found on tomb walls and in papyri attest to the developed industry and the significant role of self-care in the lives of Egyptians.

The ancient Egyptians attached great importance to hygiene and self-care. The Egyptians’ reverence for cleanliness (especially the priesthood) was noted by Herodotus in his “Histories” (circa 440 BCE), observing that they “prefer neatness to beauty.” For washing, they used water purified by adding sodium salts and a special cleansing paste made of a mixture of ash and fuller’s earth, which had a degreasing and exfoliating effect.

They used twigs, sticks, or pieces of cloth as “toothbrushes,” and the “toothpaste” was made from crushed plant roots. Herbal decoctions were used for mouth rinses to freshen breath. Teeth were cleaned with soda. To eliminate unpleasant breath odor, they chewed kify balls—aromatic substances composed of 16 components (dry frankincense, pine seeds, melon, pistachios, juniper, cinnamon, honey, etc.). The skin was anointed with perfumed oils (in a dry and hot climate, this not only gave the body a pleasant smell but also protected the skin from dehydration). There were ointments known for cleansing and rejuvenating the skin, removing spots and pimples, as well as depilatory agents.

Both women and men lined their eyes (to protect from the scorching sun), painted their lips, and blushed their cheeks. Eye makeup was made from honey, ground ochre, galena, gray or black lead sulfide, malachite, green copper hydroxycarbonate, as well as technical carbon, less often antimony, and stibnite. Palettes with paint were often made in the form of animals, birds, and reptiles. According to research by the American Chemical Society, ancient Egyptians intentionally added lead to cosmetics, which, in combination with salt, promoted the release of nitric oxide in the body, stimulating the immune system and preventing conjunctivitis.

Cosmetic boxes found in tombs contained various body care items (jars, cups, razors, and applicators). The main difference between modern cosmetics and ancient Egyptian cosmetics lies in the materials used in their preparation: modern cosmetics contain essential oils and alcohol, while ancient ones contain oils and fat infused with plant essences, flowers, and spices. The cheapest perfumes were simply water in which crushed lotus flowers were soaked, while the most expensive ones could include dozens of different aromatic substances. Aromatic oils protected the skin from dehydration and sunburns, so warriors and craftsmen were supplied with them along with provisions.

The production of perfumes continued in Egypt into the Hellenistic period. The famous Queen Cleopatra (69-30 BCE) even owned a real perfume factory on the shores of the Dead Sea. During excavations, archaeologists found not only the remains of buildings but also cauldrons, pots for evaporation and boiling, and hand mills for grinding herbs and roots. Cleopatra shared her knowledge on this subject in the book “On Cosmetics,” the first known cosmetic guide in history, which included recipes for making lipstick, blush, powder, etc. Some of these recipes have survived to this day.

Tattoos

The tattoos of ancient Egyptians can be judged by the mummies found with them and by decorative images. Typically, tattoos were simple (dots, circles) on the hands, thighs, abdomen, and chin. They were done by dancers, artists, or servants of particular cults (Hathor, Bes). Also, drawings made with henna have been found on some mummies, indicating an attempt by embalmers to give the body a natural appearance or to adorn oneself during life.