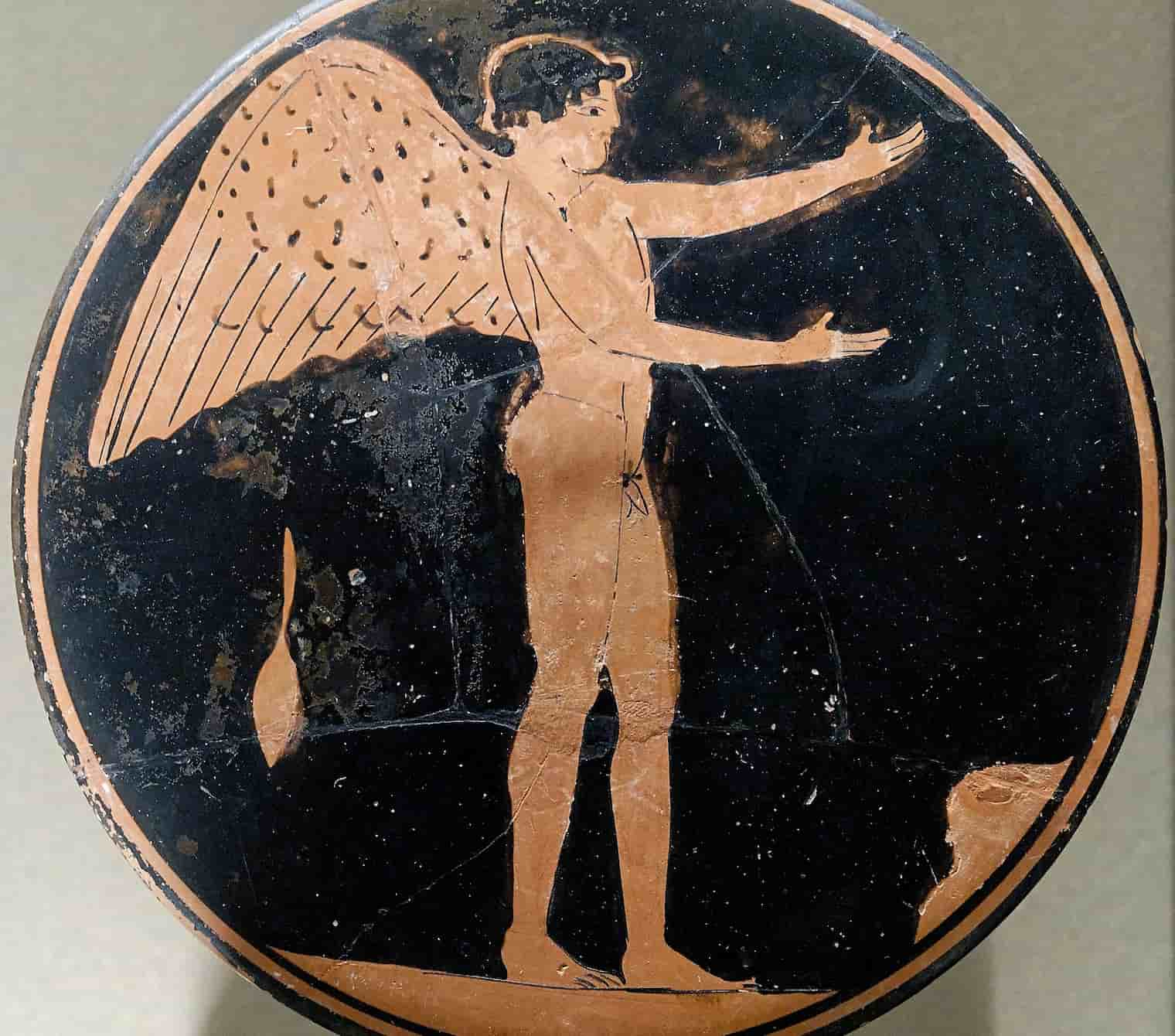

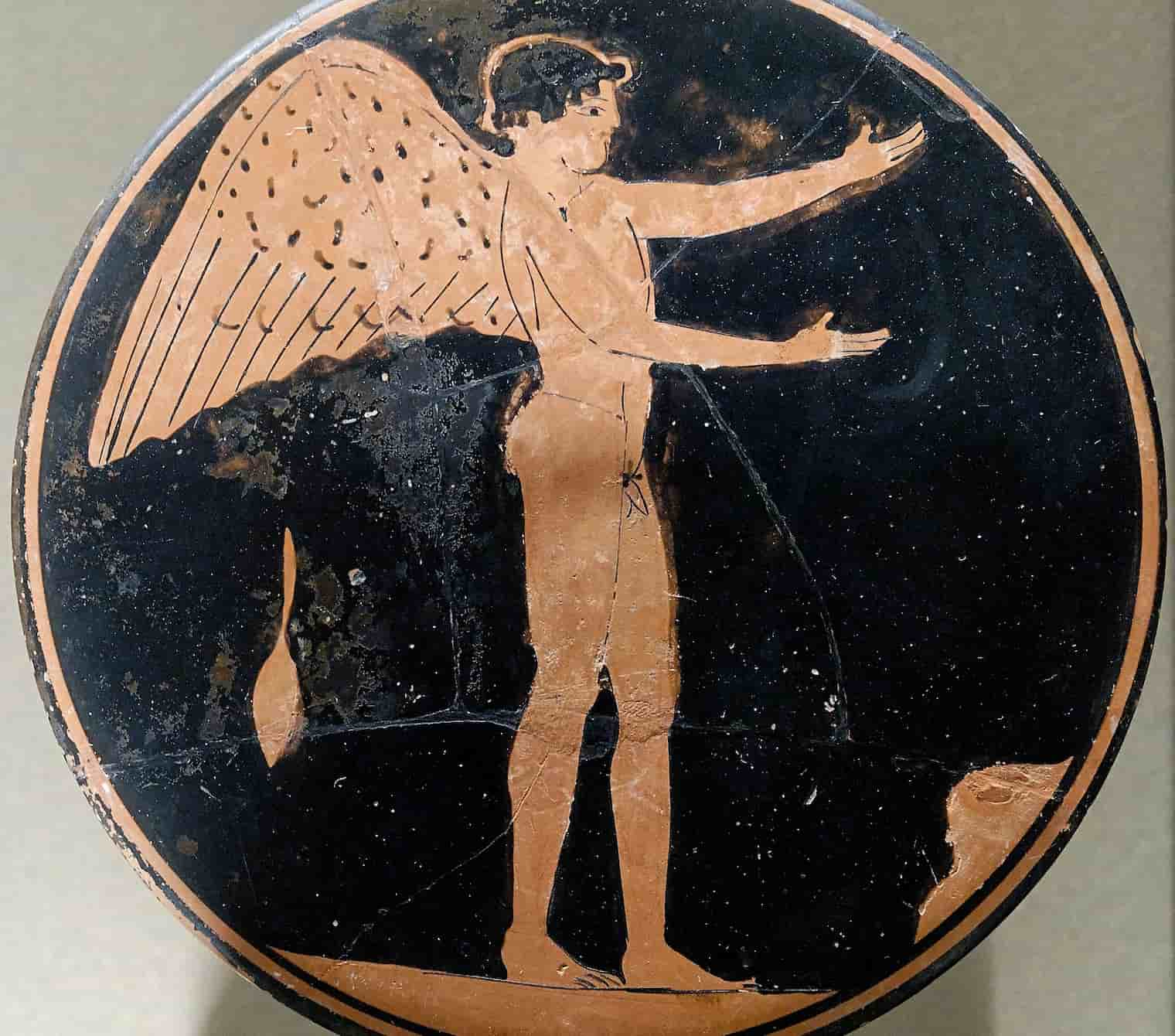

Daemon: Meaning, Origin, and History

Latin-speaking philosophers gradually transpose the concept of daemon into their own language, notably to the soul and genius.

Latin-speaking philosophers gradually transpose the concept of daemon into their own language, notably to the soul and genius.