A new combination therapy could combat diabetes at its root by increasing the number of insulin-producing beta cells. In experiments on mice implanted with human beta cells, the tested medications improved the proliferation, function, and lifespan of these body’s own insulin producers.

Future studies will aim to show whether the therapy is also effective and safe in humans.

Worldwide, about 537 million people suffer from diabetes. Forecasts suggest that this number could more than double by 2050. The main symptom is a disrupted regulation of blood sugar by the hormone insulin. In type 1 diabetes, the immune system attacks and destroys the insulin-producing beta cells, resulting in a lack of insulin. People with type 2 diabetes, on the other hand, develop resistance to insulin, which leads to an overload of beta cells and, in the long term, also results in their destruction.

Combination with Known Diabetes Medication

A team led by Carolina Rosselot from Mount Sinai Hospital in New York has now tested a therapy in mice that could potentially help regenerate the body’s own beta cells and restart insulin production. “The number of insulin-producing beta cells is reduced in most people with diabetes, but most still have some beta cells left,” the researchers explain. The new therapy aims at these remaining beta cells.

Previous drug screenings had shown that inhibition of the so-called dual tyrosine-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A) can promote the proliferation of human beta cells in cell cultures. This effect is enhanced by classic diabetes medications, the so-called GLP1 receptor agonists – these active ingredients include semaglutide, known as the “weight loss injection.

“

“Until now, however, it was unclear whether this effect would also manifest in the living organism,” the team writes. “It was also unknown how the drug combination affects the survival of beta cells.

“

Human Beta Cells in Mice

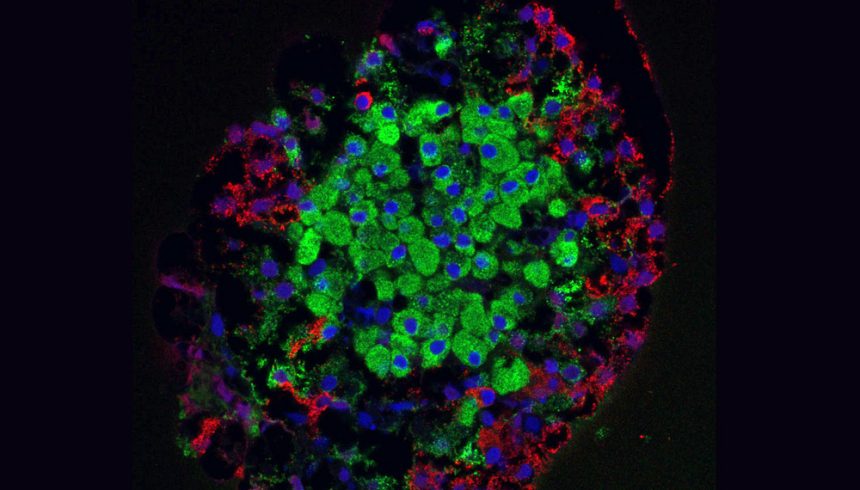

To clarify these questions, Rosselot and her colleagues implanted a small number of human beta cells into mice that had been bred as model organisms for type 1 and type 2 diabetes. They then treated the animals with a combination therapy of the DYRK1A inhibitor harmine and the GLP1 receptor agonist exendin-4. Using a special imaging technique, they recorded the number of beta cells.

And indeed: After three months, the number of beta cells in the treated animals had increased four to sevenfold. “The proliferation of beta cells occurred through an increased cell division rate, improved cell function, and increased survival rate,” the team reports.

Human Studies Planned

“This is the first time that a drug treatment has been shown to increase the number of human beta cells in vivo,” says co-author Adolfo Garcia-Ocaña from the City of Hope Beckman Research Institute in California. “This research gives hope for the use of future regenerative therapies to treat hundreds of millions of people with diabetes.”

However, it is still unclear whether the combination therapy is safe and effective in humans. Following the promising results from their animal experiments, the team is now planning clinical studies in humans. In doing so, the researchers also want to try to use immunomodulators to prevent the immune system from immediately destroying the new beta cells in patients with type 1 diabetes.