Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin had devoted her life to finding the molecular structure of medically important natural chemicals such as antibiotics, vitamins, and proteins. Being the only British woman scientist to receive a Nobel Prize in science, Hodgkin‘s dedication to world peace and her efforts to promote science and education in developing countries have earned her the appreciation and respect of many people. Long before women were staying in the workforce after marriage, she raised three children while conducting pioneering scientific research in a challenging career.

Who was Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin?

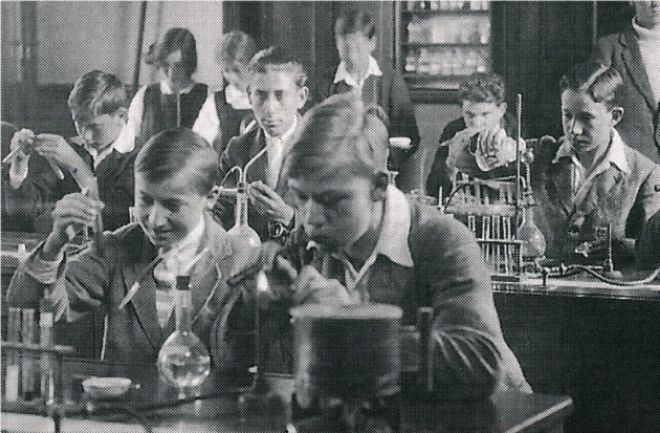

Dorothy Crowfoot, the eldest of the four daughters of British colonial ruler and archaeologist parents, grew her first crystals in a small chemistry class at the age of 10 and had a passion for it for the rest of her life. In 1928, she got admitted to study at Somerville College, one of Oxford’s women’s colleges. She graduated with honors and in 1932 went to Cambridge to study for a doctorate with John Desmond Bernal. As a brilliant crystallography expert, leftist thinker, and activist, Bernal started to work on biological molecules. Hodgkin became his closest assistant and shared his passionate socialist principles.

The natural chemical activities of the human body are based on the specific three-dimensional arrangement of the bond formed by tens, hundreds, and even thousands of atoms in each molecule. By sending an X-ray beam to the pure crystal of a substance and measuring the position and intensity of the scattered rays, it is possible to reconstruct the positions of the atoms relative to each other. This technique, X-ray crystallography, was first shown in 1912 by William and Lawrence Bragg. Bernal and Hodgkin were the first to use this method on complex biological molecules like digestive lactation pepsin.

In 1943, Hodgkin returned to Oxford University. She became a research assistant and professor of organic chemistry at Somerville College and received funding from the Robert Robinson University Museum to establish her X-ray laboratory. The protein hormone almost immediately affected the insulin levels, but the molecule was too big to find a quick solution, and the apparatus was too primitive. It took over 30 years to discover its complex structure.

Discovering the structures of vitamin B12 and insulin

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin met Thomas Hodgkin shortly after returning to Oxford; they married in December 1937. Their kids were born between 1938 and 1946, during which she continued her research. Penicillin was isolated by researchers in the Dunn School of Pathology in Oxford and was first tested on people in 1941. During the Second World War, it became a priority to analyze the arrangement of up to two dozen atoms to accomplish the mass production of medicine. Until Victory Day in May 1945, Hodgkin was able to resolve the dispute among chemists and demonstrate that even if the chemical formula was not known, she could reveal the structure of X-ray crystallography. She took the first X-ray photograph of insulin.

As her fame grew, more and more students and colleagues came from all over the world to see her. Her second most important achievement was discovering the structure of vitamin B12 in 1955, which later allowed the treatment of malignant anemia.

After receiving several awards, she earned the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964. Her most known accomplishment was the discovery of the structure of insulin, which is made of thousands of atoms, and she finally completed its structure in 1969.

A passionate peace campaigner

After winning the Nobel Prize, Hodgkin understood that her assistance could be required in some of her disciplines. In 1975, she became president of the Pugwash Conferences for Science and World Relations, bringing together scientists from the East and West to campaign against nuclear weapons; she supported peace organizations in Vietnam. She had fought against university budget cuts as rector of the University of Bristol since 1971. She has made numerous visits to China, India, and other developing countries, encouraging the exchange of students and scientists to the more resourceful institutions of the developed world, and has called her Sommerville student Prime Minister Thatcher to engage in dialogue with the Soviet Union.

Despite all of her fame, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin was polite, humble, and silent. She encouraged many women to pursue a career in crystallography, partly as a role model, and partly by giving direct help and support. Throughout her life, she showed great courage not only in establishing a new field of scientific research but also in dealing with ever-increasing arthritis pain that started when she was 28 years old. Despite being in a wheelchair, she made a final visit to Beijing in the summer of 1993 for the International Crystallography Congress. Her friends and colleagues from all over the world were excited and enthusiastic to see this person who devoted her life to taking part in a great scientific adventure.

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin quotes

- “I was captured for life by chemistry and by crystals.”

- “I once wrote a lecture for Manchester University called Moments of Discovery in which I said that there are two moments that are important. There’s the moment when you know you can find out the answer and that’s the period you are sleepless before you know what it is. When you’ve got it and know what it is, then you can rest easy.”

- “The detailed geometry of the coenzyme molecule as a whole is fascinating in its complexity.”