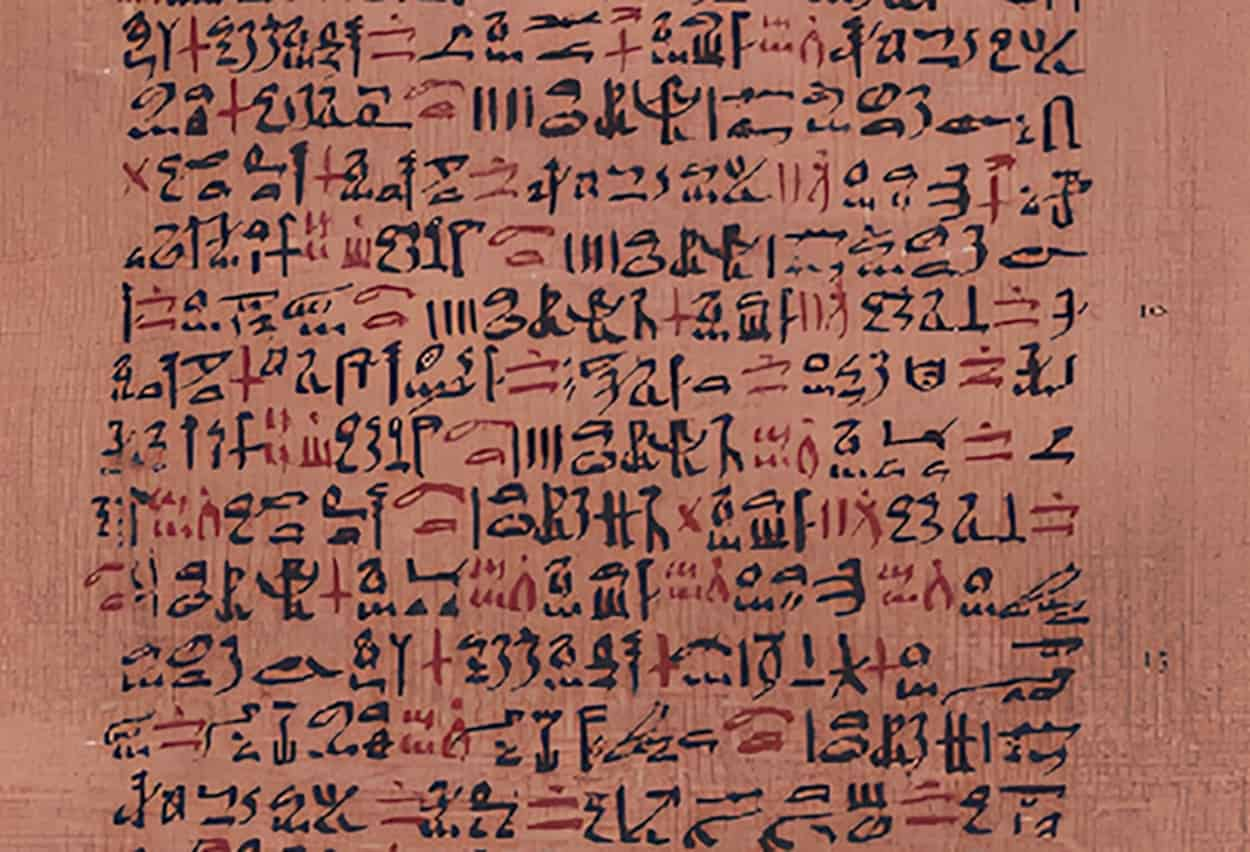

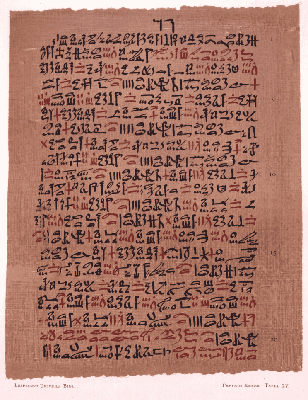

The Ebers Papyrus is one of the oldest known medical treatises; it dates back to the 16th century BCE, during the reign of Amenhotep I. It’s the most important text for understanding ancient Egyptian medicine. It appears as a list of remedy recipes with a brief indication of the ailment to be treated. It’s difficult to interpret because some medical terms remain mysterious and most substances have not been identified. It’s often regarded as the emergence of medical and pharmacological thought in a religious or magical universe.

Discovery, Translations, and Preservation

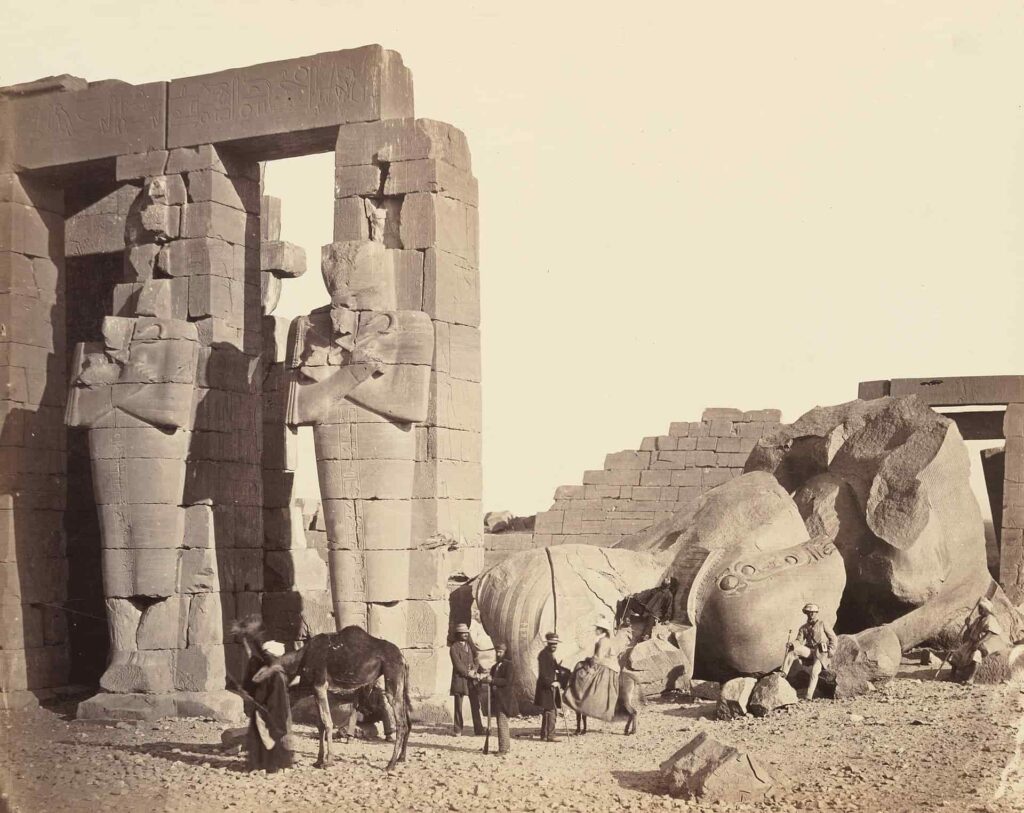

The Ebers Papyrus was part of a clandestine find under poorly known circumstances. It was likely a chest or a small library from the Ramesseum, also containing the Edwin Smith Papyrus and the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.

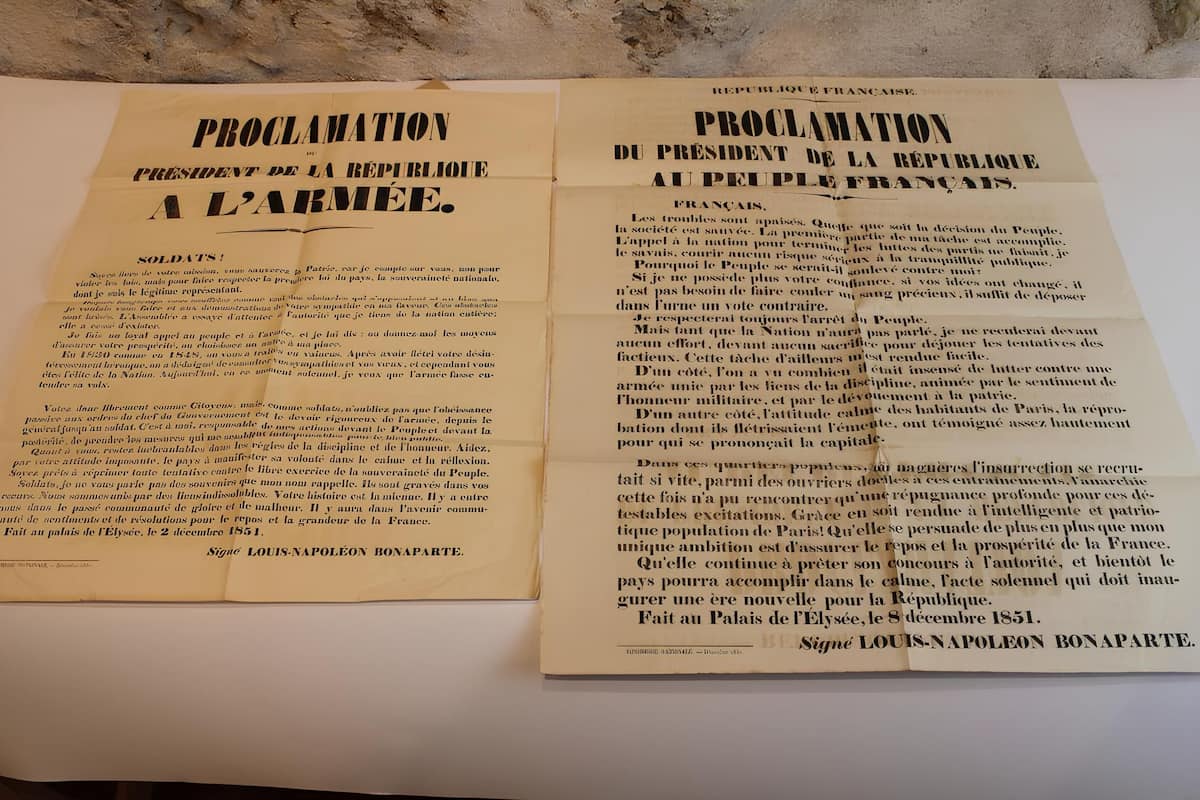

In 1862, in Luxor, the lot came into the possession of Edwin Smith, who kept the Smith papyrus for himself and sold the other two. The Ebers Papyrus was purchased by the German Egyptologist Georg Moritz Ebers on behalf of the University of Leipzig library.

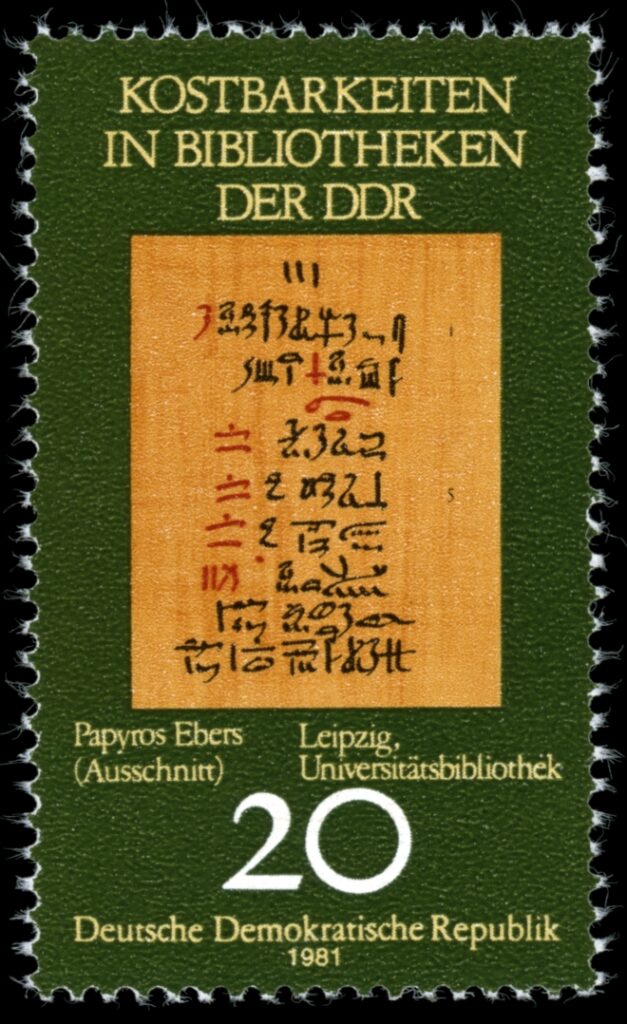

It was Ebers who named and published the papyrus in 1875. It’s a facsimile reproduction. Ebers didn’t attempt a translation, but provided an introduction with comments and an Egyptian-Latin glossary.

Early Translations

In 1890, Heinrich Joachim, a physician from Berlin, provided a rather controversial German translation: Papyros Ebers. Das älteste Buch über Heilkunde.

In 1937, Bendix Ebbell published a new translation, aiming to give precise identifications to the names of diseases, plants, and minerals used.

From 1954 to 1963, under the direction of Hermann Grapow, the Ebers Papyrus was part of the large German edition of Egyptian medical texts in eight volumes, the Grundrisse der Medizin der alten Ägypter (often abbreviated in French as Grundriss).

The first French translation (partial translation) was by Gustave Lefebvre, who provided excerpts in his Essay on Egyptian Medicine in the Pharaonic Period (1956).

In 1987, Paul Ghalioungui published a new English translation.

Preservation

In Leipzig, in the 19th century, the Ebers manuscript was cut into twenty-nine pieces to be placed under glass. A transcription from hieratic to hieroglyphs was published in 1913 by Walter Wreszinski, which divided the one hundred and ten pages of the original manuscript into 877 numbered sections.

The original manuscript is complete, in perfect condition, written in exceptional hieratic quality, and easily readable from beginning to end.

During World War II, the manuscript was protected in the Deutsche Bank vault in Leipzig, then moved and safely housed at Rochlitz Castle (Rochlitz, sixty kilometers southeast of Leipzig). According to an anonymous testimony published in 1951, when the manuscript was found in 1945, it was not inside the castle but hidden in the kennel under a pile of rubbish. Seventeen pages out of one hundred and ten were lost and four were damaged (due to the broken glass protection).

The Ebers Papyrus is still preserved in the University Library of Leipzig. Like all papyri, the greatest threats are excessive light and humidity.

It’s one of the longest written documents found in ancient Egypt. The scroll consists of one hundred and ten pages (columns); it’s about twenty meters long by thirty centimeters wide, in forty-eight sheets of about forty centimeters long, glued in such a way that the right edge of one sheet covers the left edge of the other, with the text read from right to left.

Titles and quantities are written in red ink, the rest in black. The author is unknown, but the text appears to have been written by a single highly skilled scribe. There are no spaces between words (usual practice), a few mistakes, and some missing words (omitted) have been added in the margin; their placement in the text is indicated by a red X.

It’s the most important medical work from ancient Egypt because it’s a guide presenting the entirety of pathology for a physician in their daily practice, with corresponding prescriptions. “Nowhere else will you find as much information to define the medical thought of the time.”

Dating

The Ebers Papyrus gathers texts from different dates and origins, which can be divided into groups bringing together several successive paragraphs. It appears as a compilation of older texts to which “new recipes” are added. This represents a long tradition of empirical knowledge and observations.

It was mainly written in the 16th century, around 1550 BC, or during the reign of Amenhotep I. Some Egyptologists give more recent dates and cite instead the reign of Amenhotep III in the 14th or 15th century (variable date according to Egyptologists).

Furthermore, the Ebers Papyrus contains information on the date of Ramses II’s succession to the throne of Egypt. Ramses II succeeded his father around 1304 or 1279 – 1278. The date varies depending on how the Sothic date of this papyrus is interpreted.

The most recent dating is based on the style of writing, comparison with other similar manuscripts, and the presence of a calendar on the back mentioning the ninth year of the reign of Amenhotep I (late 16th century BCE). A carbon-14 dating, conducted in 2014, confirms these data (around 1500 BCE).

Contents

The Ebers Papyrus contains exactly 877 formulas (recipes organized into paragraphs from Eb.1 to Eb. 877). It doesn’t present itself as a modern treaty but rather as a formulary (a list of prescriptions) where diseases are most often named or described concisely rather than diagnosed.

It includes a prologue (Eb.1 to Eb.3) of magical protection formulas aimed at protecting the physician from the demons that cause diseases.

From Eb.4, the actual medical compendium begins, which can be divided into thirty-three groups, each consisting of a list of recipes for the same ailment or type of ailment. In the following presentation, the term “large group” can mean both the length of the text and its importance for understanding Egyptian medicine.

Large Group 1 (Eb.4 to 187) deals with diseases inside the body, naming the main causes and corresponding recipes. It includes diarrhea, intestinal worms, and pains and burns during defecation.

Large Group 2 (Eb. 188 to Eb. 220) is devoted to diseases of the “entrance/opening of the inside-ib,” meaning the exits of all the body’s ducts connecting the organs (such as the aerodigestive entrances).

Group 3 (Eb. 221 to Eb. 241) deals with diseases associated with the heart-haty; Group 4 (Eb.242 to Eb. 260) with protective ointments and diseases of the head; Group 5 (Eb. 261 to Eb. 283) with urinary conditions; Group 6 (Eb. 284 to Eb. 293) concerns nutrition.

Group 7 (Eb. 294 to Eb. 304) is intended to combat setet (pathogenic beings circulating in the body’s ducts); Group 8 (Eb. 305 to Eb. 325) against the secretion-seryt causing cough; and Group 9 (Eb. 326 to Eb. 335) against parasites-gehou responsible for wheezing.

Large Group 10 (Eb. 336 to Eb. 431) deals with eye diseases.

Group 11 (Eb. 432 to Eb. 436) deals with bites; Group 12 (Eb. 437 to Eb. 476) with hair care; Group 13 (Eb. 477 to Eb. 481) with liver diseases; Group 14 (Eb. 482 to Eb. 514) with burns, blows, and scars; and Group 15 (Eb. 515 to Eb. 542) with wounds and hemorrhages.

Group 16 (Eb. 543 to Eb. 550) deals with pathological formations and secretions; Group 17 (Eb.551 to Eb. 555) with abscesses-benout; Group 18 (Eb.556 to Eb. 591) with swellings-chefout; and Group 19 (Eb. 592 to Eb. 602) with blood that eats and substances that corrode.

Group 20 (Eb. 603 to Eb. 615) is dedicated to leg conditions; Group 21 (Eb. 616 to Eb. 626) to fingers and toes.

Large Group 22 (Eb. 627 to Eb. 696) concerns the ducts-met.

Group 23 (Eb. 697 to Eb. 704) deals with tongue conditions; Group 24 (Eb. 705 to Eb. 738) with skin and body surface; Group 25 (Eb. 739 to Eb. 749) with teeth.

Group 26 (Eb. 750 to Eb. 756) deals with pestilential diseases and demons; Group 27 (Eb. 757 to Eb. 760) with the impact of the right side by the substance-rouyt; Group 28 (Eb. 761 to Eb. 763) impacts by the exudate-rech.

Group 29 (Eb. 764 to Eb. 782) deals with ear conditions.

Group 30 (Eb. 783 to Eb. 839) is devoted to remedies for women.

Group 31 (Eb. 840 to Eb. 853) concerns remedies for the household (protecting against undesirable animals).

Large Group 32 (Eb. 854 to Eb. 856) consists of the “Treatise on the Heart” and the treatise on oukhedou (circulating pathogenic substances).

Large Group 33 (Eb. 857 to Eb. 877) represents the “Treatise on Tumors.”

Magical Protections

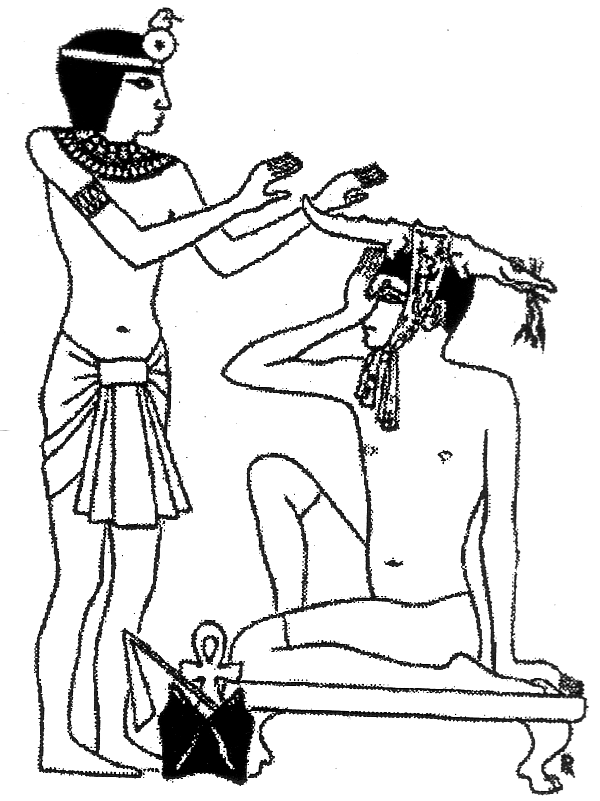

The prologue of the Ebers Papyrus includes several protection rituals. These are invocations or prayers to be recited before touching the patient, applying medication, a bandage, or removing such a bandage.

These texts are written in the first person; they have been interpreted as being spoken by the patient or by the physician on behalf of the patient. However, according to Bardinet, they were pronounced by the physician for his own protection.

The physician invokes protective gods, mainly Ra, Isis, and Horus, against malevolent (demonic) or opposing forces (the god Seth). According to Bardinet, the physician seeks to magically identify with Horus in his mythical struggle against Seth by directly addressing Isis, Horus’s protective mother. “Daily medical activity will ultimately reproduce the constantly renewed conflict between Horus and Seth, between the organized world and the disorganized and wild world.”

The patient is also assimilated to Horus, but to Horus as a child incapable of defending himself, while the physician is the adult and active Horus. Thus, the physician and his patient are close and fight together. According to the Grundriss, the physician is the magical substitute for the patient; Bardinet disagrees with this interpretation, as “the physician never takes on the patient’s illness himself.”

Magical rituals are found in other parts of the papyrus, particularly in difficult or dangerous situations. These prayers refer to mythical battles, repeated daily, such as those of the crew of the solar barge. The physician can also be aggressive, casting curses against demons and malevolent beings to disrupt their harmful world.

Medical Knowledge

Diverse Approaches

The various translations of the Ebers Papyrus imply diverse interpretations, particularly regarding anatomical and pathological denominations, names of animals, plants, and minerals. Not all Egyptian terms have corresponding modern terms. Early versions, like Ebbell’s 1937 version, which claim to provide precise identifications for each Egyptian term, are considered outdated by modern Egyptologists. These older versions are still quite often referenced.

Conversely, and for the same reason, authors like Gustave Lefebvre considered Egyptian knowledge to be imprecise or undeveloped. According to Bardinet, this knowledge is simply different and must be studied differently depending on its context. Bardinet gives an example, concerning anatomy, of the current technical vocabulary of butchery (such as beef cutting), which indeed represents precise knowledge adapted to practical use.

Another approach is to seek analogies between Egyptian and Greek medicine, with the idea of an influence of the former on the latter, which remains hypothetical. Greek concepts (such as phlegm, miasma, etc.) are then used to approach Egyptian terms. According to Bardinet, the flaws are the same as those of modern identifications: Egyptian medical thought is diluted in a context that is not its own, appearing as approximate or even childish.

The medical interpretations of the Ebers Papyrus are made for two different purposes: “understanding from the outside,” approaching the pathological reality of ancient Egypt (by comparing the text with other historical data and current knowledge), and “understanding from the inside,” approaching Egyptian medical thought (in this case, exact modern diagnosis is less important).

According to Bardinet, one must not confuse the fact that a situation may, more or less plausibly, correspond to a modern diagnosis (such as leprosy, cancer, myocardial infarction, etc.) with the false idea that Egyptian physicians already had modern ideas. Here, the search for and statement of a precise retrospective diagnosis introduce foreign ideas into Egyptian medicine.

Anatomical and Physiological Representations

The constituent elements of the body are not considered to have intrinsic properties; they are subject to higher forces of divine origin. The elements of the body (substances, liquids, breath, etc.) come from a primordial liquid universe, the Noun. All gods and beings of creation originate from it, through processes of generation, life, and death. These are processes of binding, nurturing, and generating (nourishing blood, milk, semen, etc.), opposed to processes of dilution, blocking, or destruction (blood that eats, corrosive substances, etc.). These processes themselves are considered to be living beings.

In the Ebers Papyrus, the main concepts concerning the structure and functioning of the body are the heart-haty (the heart organ and its major vessels, which are central and anterior) and the interior-ib (which fills the shet, the body cavity corresponding to the thoracic and abdominal cavities, and extends into the limbs). The heart-haty is the seat of consciousness, of the will that carries out desires, closely related to the interior-ib, the seat of sensations and emotions.

The entrance/opening of the ib, or ro-ib, represents the stomach, the upper digestive tract. At is called any part of the body that has a name. According to Grapow and Lefebvre, embalmers and physicians had about a hundred words to designate the different parts of the body.

The body is traversed by ducts-met with their own walls through which bodily fluids, nourishing substances, and vital breath circulate. In ancient Egypt, the human body “is an animated body and not an incarnated soul.”

Main Pathogenic Entities

Disease is linked to direct divine interventions. It most often comes from the outside, in the form of a demon, a dead person (deceased), a harmful breath, or “animated substance-beings” that enter the body, particularly through its orifices.

Disease manifests as displacements and false paths, various obstacles to the natural circulation of bodily fluids and secretions. Disease is a struggle between the animating breaths of binding and formation and the disruptive breaths of dissolution and disorganization. This struggle often takes place in the ducts-met, which can be too rigid, blocked, worn, or distended.

According to Bardinet, this divine or magical context did not prevent the emergence of medical reflection, based on daily observation of repetitive phenomena, in search of a “logic” that combines facts (pathological reality) with medical speculation, to build a practice. “We have here writings composed by physicians, for the use of other physicians.”

The Ebers Papyrus mentions four major circulating pathogenic factors:

- The âaâ is a bodily fluid that seems to refer to the water of the Nile; like it, it is a fertilizing liquid, a seed. In pathological cases, âaâ is a fluid emitted by the bodies of demons, capable of transforming into other “parasitic” substances (living pathogenic substances).

- Setet are living decomposition substances that are evacuated through the lower abdomen but can cause pain, vomiting, and discharge from the orifices of the head by their death or blockage.

- The oukhedou would be the pathogenic emanation of the vital force of excrement. It is a bodily substance that opposes nourishing blood and can associate with it, to reverse it into eating blood or blood that eats. Oukhedou are the origin of pus formation and putrid phenomena.

The ouhaou are believed to originate from the oukhedou, coming from the inside they manifest on the outside of the body, notably through skin inflammation.

The Treatise of the Heart

The papyrus contains a “treatise of the heart” represented by the passage Eb. 854 to Eb. 856. It begins with three successive titles: “The Physician’s Secret. Knowing the Movements of the Heart-haty. Knowing the Heart-haty.”

Interpretations differ among authors. For some ancient authors, it would be a treatise dealing with anatomy (knowing the heart) and physiology (knowing the movements and functioning of the heart). These authors note that the heart is the center of blood irrigation, with vessels attached to all parts of the body, and that the Egyptian physician palpates the body parts and ducts-met to examine the beats, take the pulse, or even count them.

For other authors (modern ones), it is not only about the heart organ in the modern sense, but about an Egyptian heart-haty capable of moving (changing position). It would then be a treatise on medical diagnosis aimed at establishing the position and involvement of the heart-haty. Pulse-taking is also recognized, but it is not about counting it but about “taking a measure” (evaluating) a diseased state. Palpation is part of a qualitative overall assessment aimed at assessing the nature and extent of the ailment throughout the body.

The heart is described in its relationships with the interior-ib. In its normal state, it is in a perfect and stable position on its fixed support (the meket); in its diseased state, it can start dancing, fluttering its wings, banging against the walls, or falling by sinking into the depth. The heart-haty “speaks in front of each conduit-met of every part of the body.”

This treatise lists ducts-met that start from the head orifices to reach the heart-haty. From there, they go towards the inside (interior-ib) and the four limbs, to gather at the anus. The “treatise of the heart” would not really be a “cardiology book” but rather a “book of paths” of pathogenic entities.

The Treatise of Tumors

This treatise is represented by the passages Eb. 857 to Eb. 877. “It is one of the greatest texts of Egyptian medicine and also one of the most difficult texts to interpret.” It establishes a kind of differential diagnosis between different types of abscesses and tumors based on their content: those filled with pus and those filled with something else. Tumors are distinguished by their color, firmness (hard, soft…), mobility or fluctuation (literally “rolling under the fingers”), heat, and presence of pain.

Depending on the cases, the treatment consists of ointment, surgery (“treatment with a knife”), or therapeutic abstention (“prepare nothing against it”).

Swellings and tumors filled with pus are called henhenet swellings. Pus is produced internally by a corrosive substance called oukhedou that gathers externally in a “pouch” (âat). The pus derives from an upward secretion from digestion (what was intended for the formation of flesh has been transformed into pus).

Other tumors are said to be filled with “fat,” “superficial flesh,” “like something swollen with air,” liquid, or various substances. For example, tumors filled with oukhedou manifest at the extremities of the body, those of substance-sefet refer to a tar of vegetable origin, evoking necrosis or gangrene.

The most feared tumors are “those formed by the god Khonsou.” The text indicates “it is something bewitched that is before your face,” presenting itself in multiple pouches and producing secretions—shepaou—against which nothing can be done. The papyrus ends on the size-ânout “formed by the massacres of the god Khonsou.” When it is multiple and hot, nothing can be done; otherwise, it can be cured.

Pathological Interpretations

The Ebers Papyrus mainly consists of a list of formulas, and most of the time, the conciseness of the text mentioning ailments hardly allows for retrospective diagnoses. Most interpretations are based on those of Ebbell in 1937, but several are no longer accepted or considered barely plausible. As a general rule, hypotheses are accepted when they are compatible with other historical data, such as the paleopathology of Egyptian mummies.

Digestive and Thoracic Ailments

The medical compilation of the Ebers papyrus begins with what appears to be digestive pathology: diarrhea, including bloody diarrhea, constipation, and various obstructions… A large place is given to ano-rectal diseases. The mention of what could be stomach cancer is doubtful, while the pictures of cholecystitis, intestinal obstructions, and digestive hemorrhages appear plausible. Several recipes “to treat the liver” are listed, but without any corresponding clinical description.

This digestive pathology can be associated with a thoracic pathology represented by “forgetfulness, fleeing, or stabbing of the heart,” which would represent palpitations and precordial pain. A passage (Eb. 191) has been interpreted as angina pectoris, a manifestation of myocardial infarction.

“If you proceed to examine a man afflicted at the entrance of the interior-ib; and he is affected in the arm, chest, and (on) one side of the entrance of the interior-ib; and people say about it; ‘it’s the (disease) green!’ (= popular diagnosis) You shall say about it: ‘It is (something) that has entered the mouth, it is a dead person who travels through it.'”

According to Bardinet, the description may correspond, but the Egyptian author has no idea of a heart disease: it is a problem of a conduit traversed by a dead person. The recipe given aims to strengthen the patient and evacuate this pain through the anus.

Urinary and Parasitic Afflictions

Urinary pathology is represented by the substance-chepen which causes pus in the urine. Other disorders appear to be urinary retention, enuresis, and cystitis. Passages concerning “an overflow of urine that escapes” have raised the possibility of polyuria due to diabetes mellitus.

The disease by âaâ with red urine would be bilharzia. The importance of the condition is indicated by the number of recipes (about twenty). The presence of the disease in ancient Egypt is certain and extremely widespread; it was detected in nearly half of the tested mummies, but it is difficult to know what the Egyptians knew about it. According to Bardinet, the frequency of parasitic hematuria indicated less of a disease than a particular human type, those inhabited by or in relation to a god, here the god Seth, a reference to the color red.

Several intestinal worms are mentioned, including the ver-hefat, the ver-pened… Their exact identification remains debated, but given other historical data, they could represent the hookworm, the roundworm, or the Taenia saginata.

Furthermore, the mention of dracunculiasis is possible, by combining two passages (Eb.617 and Eb. 876), but more by its demonstrated existence in ancient Egypt than by the clarity of the text. According to Bardinet, Eb. 617 would be a myiasis problem, and the “7 knots” of Eb. 876 a magical conjuration, rather than an allusion to traditional treatment (see section examples of recipes).

Ocular and ENT Afflictions

An important passage is dedicated to eye diseases: about a hundred recipes are presented as intended to combat the agents of these diseases. According to Bardinet, it is always difficult to match Egyptian words with ophthalmological reality (modern terms), but the Egyptians took note of what they could observe in the eyes (water, pus, blood, harmful substances, harmful beings…). Commentators have recognized conjunctivitis, blepharitis, styes, ectropion, chalazion, corneal opacity, etc.

Cataracts would be referred to as “water rising in the eyes”, on the grounds that the Latins used the term suffusio to designate it, but cataract surgery is not mentioned (it was introduced in Egypt in the Hellenistic period).

A passage indicating “uterine secretions in the eyes” has been interpreted as a gonococcal infection (gonococcal iritis), which has been contested by others, with historians disagreeing on the presence of this condition in antiquity.

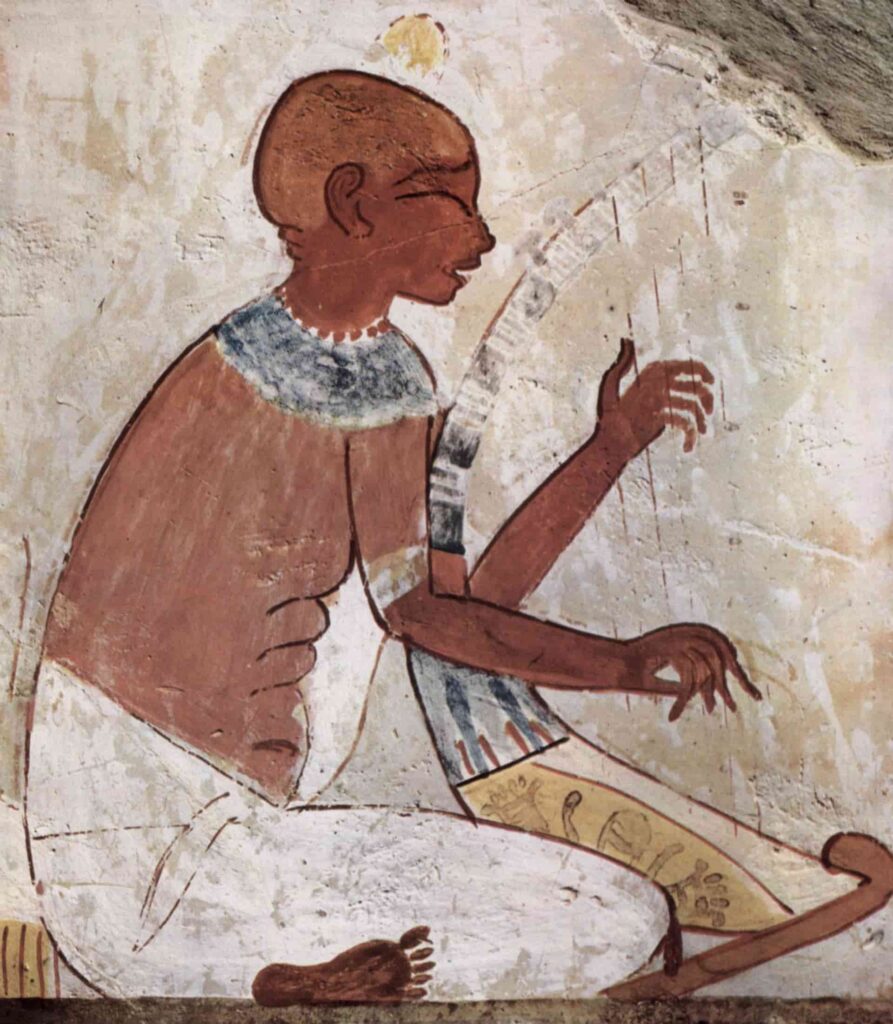

On the other hand, manifestations indicating trachoma appear plausible, as its historical character and widespread occurrence in pharaonic Egypt are widely accepted, notably as a leading cause of blindness. There are many Egyptian representations of blind musicians, especially harpists, whose eye is depicted by a line or whose eyeball lacks an iris.

The fact that recipes may contain beef liver (vitamin A) would indicate a treatment for night blindness.

Afflictions by exudate-rech would represent ENT conditions, as it makes the “seven holes of the head” (mouth, nostrils, eyes, and ears) painful, which suggests sinusitis, rhinitis, otitis, etc. Deafness is attributed to a cutting demon or heseq, that interrupts the hearing conduits.

Passages dedicated to mouth and dental conditions do not propose an ordered classification of lesions, but they are varied enough to see a set of periodontal diseases (dental caries and wear, abscesses and oral infections, gingivitis…) sometimes related to a “corrosive substance”.

In such a context, the Ebers Papyrus has the reputation of being one of the first texts in history to describe scurvy. However, this diagnosis remains improbable, as it is not confirmed by paleopathology data. Periodontal diseases found (Egyptian mummies) are common but attributed to an alteration of oral flora or to the poor quality of antiquity flours that contained mineral particles from millstones or stone mortars (sometimes the addition was deliberate to obtain a finer flour). Consumers of these flours were exposed to premature tooth wear.

Gynaecological Conditions

The Ebers Papyrus gives considerable attention to menstrual disorders: amenorrhea and dysmenorrhea. Uterine prolapse is mentioned. Recipes are provided for inflammatory conditions of the vulva, vaginitis, and endometritis. Burning sensations or odor perception have been subjected to microbiological interpretations. Commentators have noted the possibility of uterine cancer, which is likely but difficult to confirm. The same applies to breast cancer, for which there is no clear mention.

A contraceptive recipe in the form of a pessary is given “to not have a child for one, two, or three years” (Eb. 783).

Around twenty other preparations (vaginal preparations, suppositories, fumigations, etc.) are intended to facilitate childbirth and placental expulsion. Egyptian women gave birth on a “birthing brick.” Recipe Eb. 789 specifies that the medication should impregnate “the brick lined with fabric.” According to Bardinet, “this little text teaches us in passing that they had thought to stuff it.”

Other recipes address breast conditions and breastfeeding problems. A magical formula, called the “conjuration of the breast,” is provided (Eb. 811): “This is the breast where Isis was affected in the marsh of Chemmis when she gave birth to Shou and Tefnout. What she did was conjure the breasts with the iar plant, with a pod of the seneb plant, with the bekat part of the reed—all this to drive away the action of a dead man, a dead woman, and so on. This will be prepared in the form of a band turned to the left, which will be placed where the action of the dead man or woman is (with the following words): Do not cause evacuation! Do not produce substances that corrode! Do not produce blood! Be careful that darkness does not develop against humans! Words are to be said about [each of the ingredients already mentioned] and about the band turned to the left, to which seven knots are made.”

Children are rarely mentioned. There are predictions about the fate of the newborn such as “If one hears its plaintive voice, it means that it will die. If it places its face toward the ground, it also means that it will die” (Eb. 839). A recipe is given against incessant crying and screaming (Eb. 782).

There is also a recipe for bleeding after circumcision (see the recipe example section). The mummy of Prince Sipaari or Ahmose-Pairy (New Kingdom) at the age of five or six, bore traces of circumcision.

Tumors and Swellings

The treatise on tumors has been widely interpreted. Tumors related to the conduits-met would be aneurysms. The authors propose diagnoses for each paragraph: scrofula, inguinal hernia, varicose veins, cystic tumor, polypoid tumor, etc. The presence of cancer or neoplastic tumors can be indirectly deduced, but there is no clear indication of malignancy, except for the tumors of the god Khonsou.

States of liquid swelling, more or less generalized, have been interpreted as equivalents to the historical diagnosis of dropsy (obsolete medical term) corresponding to edemas or effusions (for example, ascites) related to states of heart, liver, or kidney failure, or parasitic or malnutrition-related conditions.

The swelling-ânout by “massacre of the god Khonsou” would be a mention of leprosy; this diagnosis, proposed by Ebbell in 1937, is no longer accepted by more modern authors by comparison with other historical data, particularly paleopathology.

Pestilential and Other Afflictions

The pestilences occurring at certain times are attributed to demons-nesyt or “a morbid breath that passes.” The Ebers Papyrus offers protection recipes, such as this one (Eb. 756): “Other (remedy): testicles of a newborn donkey. It will be finely ground, put in wine, and drunk by the man. Then he (the demon-nesyt) must immediately flee.” Here, the donkey would be a Sethian animal, whose testicles represent the formidable seed of the god who drives away demons.

Several inflammatory skin conditions are mentioned under the term, among others, kakaout. This term has persisted in Coptic to mean “pustule, blister.” Some authors relate it to the Arabic kalkal, “to swell, to fill with air.”

These conditions have been interpreted as erysipelas (streptococcal infection) and anthrax (staphylococcal infection). Others have also seen herpes, shingles, smallpox, etc. All of these diagnoses are considered “provisional suggestions.”

Furthermore, protective ointments to cure headaches and prevent relapses suggest the existence of migraines. Tremors are attributed to substances-setet or substances-daout that block the conduits-met. A recipe for finger tremor aims to “drive away (the substances that cause) the tremor found in the fingers”.

Mental Afflictions

Mental disorders are mentioned in the “Book of Hearts,” such as deafness and pathological anger due to “sagging of the conduits-met,” or wear of these conduits with age, which has been interpreted as depression, dementia, or Ménière’s disease. These mentions suggest that the Egyptians did not make a fundamental distinction between mental and physical illnesses.

Pharmacopoeia

Difficulties

The Ebers Papyrus mentions several hundred substances, but for modern Egyptologists, 70 to 80% of these ingredients have not been identified. Therefore, reproducing the prescriptions is very difficult. Similarly, this lack of exact determination hardly allows for deducing the presumed mode of action (pharmacological reality in the modern sense).

The Egyptian pharmacopoeia of the time used mineral, plant, and animal substances, whose denominations do not necessarily correspond to a modern equivalent. For example, for plant substances, the Egyptians did not have the modern notion of species. A plant recognized by the Egyptians is a plant integrated into a “phytosociological unit” corresponding to a particular use, or to a different knowledge (plant categories, or elements of plants, specific to the Egyptians). In the case of gum and resin names, modern Egyptologists have abandoned the idea that an Egyptian name designates a single substance and its producer. The Egyptians were not seeking a “botanical origin” but “qualities” corresponding to their “phytoreligious” beliefs.

Substances more or less identified

Among the identified substances, the most frequently mentioned minerals are clay, copper, galena, malachite, natron, ochers, and salt (terrestrial and marine).

The most commonly identified plants are: acacia, wheat, spelt, barley, fava bean, juniper berries, frankincense, barley, pyrethrum, castor oil plant, reed, willow, sycamore, valerian… There are also vegetables (garlic, celery, peas, edible tuber, lotus…), fruits (date, fig, jujube, grape…), and spices (coriander, cumin…). The Ebers Papyrus mentions many derivative products (beers, wine, lees, oils, flours and breads, gums and resins, mucilages…).

Expressions such as “snake wood,” “image of Horus,” “image of Seth,” “baboon hair,” “mouse tail”… are names of unidentified plants (the text mentioning leaf or root).

Animal substances are represented by products such as bone marrow or teeth; fat, liver, or testicle; blood, urine, semen, or milk; bile and excrement, etc. They come from mammals, the most frequently mentioned being the donkey, cat, goat, deer, gazelle, hippopotamus, pig, mouse, and bull; for birds, it is the ostrich, swallow, and vulture; snakes, lizards, crocodiles, and turtles are mentioned, as well as fish and frogs. The Egyptians also used flies, beetles, and scorpions. Honey occupies a very important place.

Logic of use

The first commentators distinguished in the Egyptian pharmacopoeia what was “demonic” or “excremental,” belonging to a “barbaric imagination” of magicians, and active plant substances belonging to medical knowledge. Their association would be explained thus: “Respect for tradition, customer habits are partially the cause.” According to Gustave Lefebvre, “The doctors, moreover, must have given preference to the remedies of their own composition, which had at least the merit of not being repugnant or ludicrous.”

According to Bardinet, Egyptian recipes must be approached as a whole. Far from being absurd or contradictory, they present internal coherence—a logic based on presumed causes. It becomes possible to speak of medical reasoning based on “physiological considerations” (the traditional conception of the body and the world in ancient Egypt).

For example, the Egyptians believed that human generation (formation of the fetus and development of the infant) was the result of divine forces acting through paternal bone-seed, and maternal blood-milk. The same divine forces act for each particular animal (animal related to a god, see List of Egyptian deities by animal). This idea helps to understand the presence of semen, bone marrow, blood, or milk… of human or animal origin, in Egyptian recipes.

These recipes aim to capture divine forces for the benefit of the patient, such as the “blood of the horn of a black bull” (Eb. 454) used to treat scalp diseases. This blood, taken near the horn, is supposed to be of superior virtue, since it produces a black coat by nourishing the horn. Another recipe combines “boiled donkey hoof” and “bitch vulva blood” (Eb. 460), aiming to bring together the two forces of generation, bone-seed, and blood-flesh according to the invoked gods.

Excremental ingredients (sometimes called “coprotherapy”) are also considered to have autonomous vital force. They are intended to directly oppose demons or other harmful entities. It is then a repulsive action, to evacuate, chase away, or kill them as the case may be. This type of recipe “aims both to heal the patient and to protect the physician.”

Other products and means act by “mechanical” virtues: it is a matter of cooling what is too hot, softening or toning, emptying or filling, unblocking and circulating, etc.

Examples of Recipes

Examples from the Ebers Papyrus (translated by Thierry Bardinet):

- To cleanse the inside of the body: 1 cow’s milk, 1 incised fruit of the sycamore, 1 honey. It will be finely ground, cooked, and ingested for four consecutive days (Eb. 18).

- To expel the alterations found in a man’s body: castor seeds. It will be chewed and swallowed with beer until everything inside his body comes out. (Eb. 25).

- To drive away all the ailments found in one side of the inside of the body: 1 sweet clover, 1 date wine. It will be cooked in fat/oil. Dress with it (Eb. 40).

- To expel the burning substances found at the anus: 1 broad bean flour, 1 plant-djaret powder, 1 frankincense, 1 resin-ihemet, 1 galena. It will be shaped into a suppository and inserted into the anus (Eb. 155).

- The ointment with catfish skull against migraine (Eb. 250), here interpreted as the bandage on the head of a crocodile in clay with medicinal plants in its mouth.

For migraine (literally: the pains that are on one side of the head): catfish skull, fried in fat/oil. Rub the head with it, for four consecutive days (Eb. 250). - To drive away the seryt secretion that causes coughing: 1 realgar, 1 men resin, plant-ââam. It will be finely ground. (to be told to the patient) You must take seven stones and heat them in the fire. One stone will be coated with the medicine and placed in a new pot with the bottom pierced. You must insert a reed stem into the hole, and place your mouth to inhale the vapor. Do the same with each stone (Eb. 325).

- Another makeup, to open the view: 2 galena, 2 goose fat, 4 water. It will be placed in the eyes (Eb 401).

- For a burned spot on the first day: 1 peret-cheny fruit, 1 edible tuber rhizome, 1 cat’s dung. It will be mixed into a homogeneous mass with gum water and applied to it (Eb 498).

- To drive away the benout abscesses found in the teeth and make (re)grow the superficial flesh (=gum): 1 besbes plant, 1 incised fruit of the sycamore, 1 ineset plant, 1 honey, 1 terebinth resin, 1 water. It will be left at rest overnight in the dew and chewed (Eb 554).

- To extract a thorn when it is in the superficial flesh: donkey dung. It will be mixed with mucilage and placed on the orifice (entry point of the thorn) (Eb. 728).

- Remedy for an abnormal ear that concentrates pus: 1 moringa oil, 1 terebinth resin, 1 sekhepet liquid. It will be poured into the ear (Eb. 768).

- Home remedies, to prevent mosquitoes from biting (against stings): fresh moringa oil, smear with that (Eb. 846), to prevent mice from reaching something: cat fat, it will be placed on all things (Eb. 847).

- To make a woman cease to be pregnant for one year, two years, or three years: acacia part-qaa, plant-djaret, date. It will be finely ground with a vase-hénou of honey. Impregnate a plant tampon with it which will be placed in her vagina (Eb 783).

- For a painful breast: 1 calamine, 1 bull bile, 1 fly dung, 1 ochre. It will be prepared into a homogeneous mass. Rub the breast for four consecutive days (Eb. 810).

Some old translations or interpretations considered questionable:

- Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm): “wrap the emerging end of the worm around a stick and slowly extract it” (3,500 years later, this remains the standard treatment). This is a passage from recipe Eb. 876, whose translation by Bardinet is: “If you find that the affected area is red, round, like (after) a stick blow, (this) being caused by the ‘blow’ struck at all things that are in any part of the body, and for which seven knots are made (magical conjuration). You must say it is the sefet substance of a conduit-met, it is a ‘blow’ struck to a conduit-met that causes this.”

- A circumcision? : “Remedy for a foreskin (?) that is cut (circumcised) and from which blood comes out: drst, honey, cuttlefish bone, sycamore, dsjs fruit, it will be mixed and applied to it” (Eb. 732). Bardinet’s translation is “Remedy for an acacia thorn where when extracted, blood comes out: 1 plant-djaret, 1 honey, 1 nes-che, 1 sycamore, seeds of the djas plant. It will be prepared into a homogeneous mass and applied to it.”

- The recipe for continuous crying of the child (Eb. 782): “poppy capsules, wasp droppings found on walls. Mix into a mass, filter and take (by the patient) for four days. (The cries) cease immediately” (translation Lefebvre). Bardinet’s translation is: “parts-chepennou of the chepen plant, fly droppings on the wall. It will be prepared into a homogeneous mass, filtered, then absorbed for four consecutive days. (This) will stop perfectly.”

Modern translations are more cautious and do not attempt to guess precise identifications based on presumed contexts.

Birth of Pharmacognosy

The Ebers Papyrus would indicate the emergence of medical thought (observation, diagnosis, and prognosis) in a religious or magical context, but also the appearance of pharmacognosy which seeks to organize knowledge about therapeutic substances.

The structure of the recipes is a prototype of modern prescription comprising: the indication of an ailment, the naming of substances, their quantity or proportion, the type of preparation (grinding, filtering, cooking…), the vehicle or excipient (beer, water, honey, lees…), the dosage form (decoction, powder, pill, suppository, ovule…), the route of administration (oral, topical, rectal, vaginal, inhalation, fumigation…). Most recipes mention an evolutionary stage of the ailment, the time of prescription during the day, as well as the duration of treatment. Some mention the season or the age of the patient.

In 1876, after the publication of the Ebers Papyrus, Gaston Maspero formulated the following judgment: “With the little that the Egyptians knew, there may have been some merit in finding it nearly thirty centuries before our era.” Many mineral and plant substances mentioned in the papyrus retained medicinal use until the 20th century.

Several authors have sought a pharmacological interpretation supporting the presumed real effectiveness of certain ingredients. The most often cited is that of vitamin A contained in the fat and liver of animals. According to Gustave Lefebvre (with J.F. Porge), “Every bile contains cholic acid, and it is from this acid that our chemists synthetically prepare cortisone.”

Some authors believe that the infectious risk of excrements would be offset by a high immune resistance. Similarly, for the contraceptive recipe in the Ebers Papyrus, fermenting acacia gum produces lactic acid with proven spermicidal power, dates contain phytoestrogens, and honey has antiseptic properties.