In Arabic, Islam means “submission to God,” and a Muslim is a person “devoted to God.” Like Jews and Christians, Muslims are monotheists. They believe there is only one God who created the world and everything in it. In Arabic, God is called Allah, and this is also how Arab Christians refer to God. According to Muslim tradition, God has 99 names—here are just a few: The Merciful, The Compassionate, The King, The Holy, The Peaceful, The Faithful, The Protector, The Great, The Mighty, The Exalted, The Creator, The Maker, The Shaper, The Wise.

Muslims believe in angels and demons, whom God created before humans, and in prophets, most of whom are identified with biblical figures (Ibrahim is Abraham, Musa is Moses, and even Isa is Jesus Christ). Like Jews and Christians, they also await the coming of the Messiah (Mahdi) at the end of times. Islam is the fastest-growing religion in the world: today, there are more than one and a half billion followers globally.

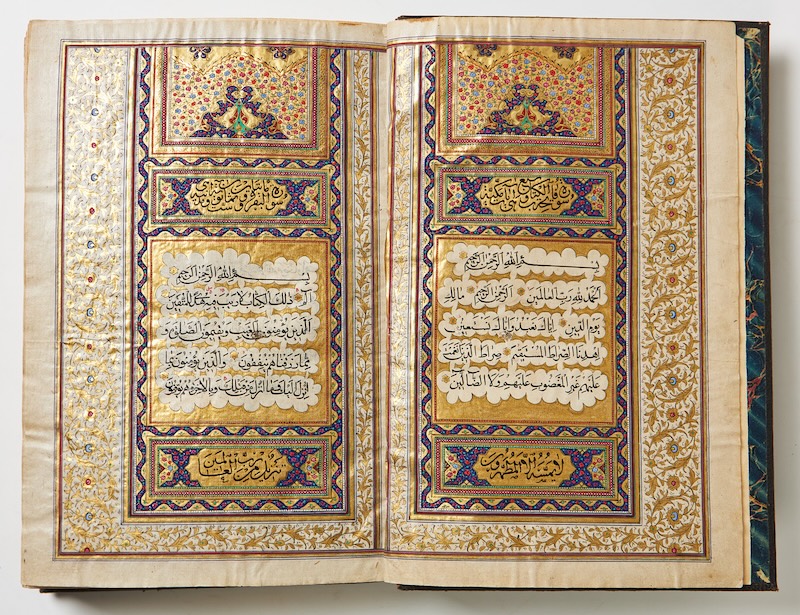

What Is the Quran?

“For Muslims, God became a book”—this statement perfectly captures the status of the Holy Scripture in Islam. In Arabic, al-Quran means “recitation aloud.” This is because this is how the Prophet Muhammad received revelations from God. One day, someone with a scroll appeared to him in a dream and commanded, “Read!” Muhammad, who was illiterate, told the stranger this, but the stranger continued to insist, squeezing the Prophet’s chest.

Frightened, Muhammad asked what exactly he should read, and then the first words of the Quran were spoken: “Read in the name of your Lord.” The mysterious stranger who appeared to Muhammad is usually identified with the archangel Gabriel. According to Muslim tradition, divine revelation to Muhammad began on the 27th of the month of Ramadan and continued for 22 years, being fully recorded only after the Prophet’s death.

The Quran states that Muhammad received the revelation in Arabic, hence the belief that only the Arabic original is the Holy Text, and any translations are just interpretations. The Quran is divided into chapters—Surahs, which in turn are divided into verses—Ayahs. The sequence of the Surahs in the Quran, with a few exceptions, is determined by their length—long ones at the beginning and shorter ones at the end. The longer Surahs are considered later and were received by Muhammad after his migration from Mecca to Medina.

Who Is Muhammad?

Muhammad is a key figure in the history of Islam, the last prophet, or the “seal of the prophets.” When mentioning his name, Muslims always add the phrase “May God bless him and grant him peace.” The main source for reconstructing Muhammad’s biography is the Muslim tradition—Sunnah (from Arabic, meaning “example” or “model”), which is a collection of stories—Hadiths—about the words and deeds of the Prophet. There are several authoritative collections of Hadiths (from the 8th to 11th centuries), whose compilers carefully studied the history of the oral transmission of all Hadiths: the chain of transmitters (from a companion of Muhammad onwards) had to be uninterrupted, and their biographies impeccable.

What do we know about Muhammad? He was born in 570 in Mecca, a city in the west of the Arabian Peninsula, where the main Arabian shrine, the Kaaba, was located. Apart from the main local shrine—the black stone (possibly of meteoric origin) embedded in the corner of the Kaaba—gods of various tribes were revered there: the Kaaba was an intertribal cult center. Muhammad was orphaned early, and his upbringing was taken over by his uncle, Abu Talib. Muhammad’s first wife was a wealthy widow named Khadijah. She and Muhammad’s cousin Ali were the first to recognize him as a prophet and accept Islam.

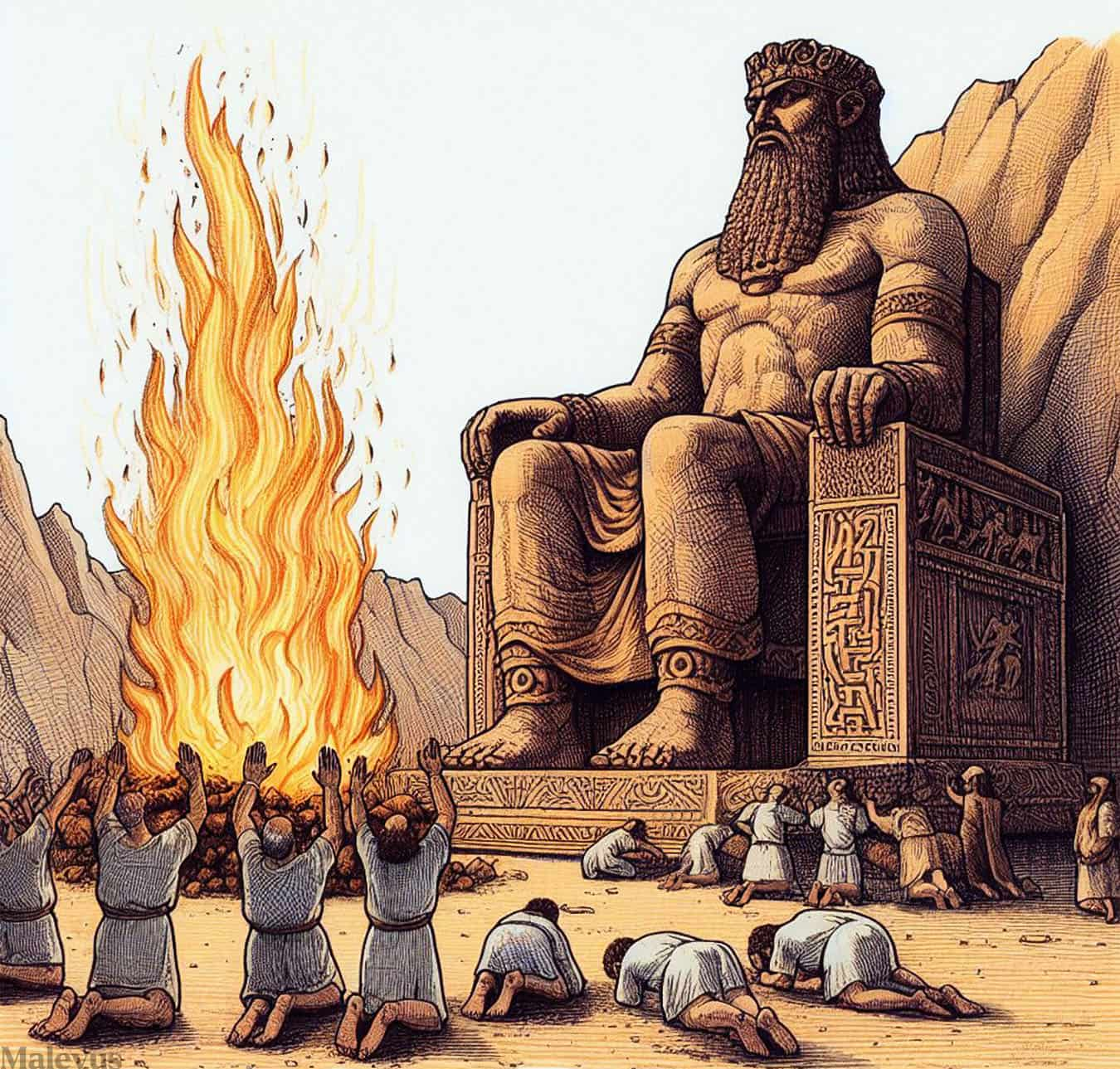

Around 610, Muhammad began his preaching, urging Arabs to reject false gods and worship the one true God. He reminded them that God had sent prophets—Abraham, Moses, Jesus—to other peoples as well, and those who rejected them faced severe punishment. However, his preaching was not successful, and after 12 years, the Prophet, along with his few supporters, had to leave Mecca.

He then settled in the city of Yathrib, where he already had more followers. This migration (Arabic: Hijra) marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar (thus, the year 2016 is 1437–1438 in the Hijri calendar), and Yathrib was first renamed the City of the Prophet—Madinat an-Nabi, and later simply the City—Medina.

Muhammad returned to Mecca a few years later, accompanied by a large army as the leader—both religious and political—of a large community. The pagan shrine, the Kaaba, was cleansed of idols and became the main sanctuary of Islam, and it remains so to this day. In 632, having almost unified the entire Arabian Peninsula, Muhammad died without having time to carry out plans for further spreading the new religion. His followers took on this task.

How Do Shiites Differ From Sunnis?

Islam is not monolithic; it consists of several branches. The most well-known and numerous branches of Islam are Sunnis (meaning “followers of the Sunnah”—although the Shiites have their own Sunnah) and Shiites (from Arabic, Shia—”followers”).

The schism that gave rise to Sunnism and Shiism occurred shortly after the death of the Prophet Muhammad and was connected with the issue of succession of power. Future Shiites believed that the successor (called Imam in Shiism) should be Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali, and that power should be passed strictly by inheritance from him. However, the majority of Muslims—future Sunnis—decided to elect their leader, the Caliph, independently.

Nevertheless, after the death of the first three elected caliphs, they chose Ali as the next leader, creating a chance to overcome disagreements. But in 661, Ali was assassinated, and the community split permanently. Ali is the only Muslim leader after Muhammad recognized by both Sunnis and Shiites. The former consider him the fourth caliph (the last of the “righteous”), while the latter consider him the first Imam and a saint. The fifth caliph of the future Sunnis was the governor of Syria, Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan, while the second Imam of the Shiites was Ali’s son and Muhammad’s grandson, Hasan.

The majority of Shiites recognize twelve Imams. After the mysterious disappearance of the last of them, Muhammad ibn al-Hasan, in 872, the doctrine of the “Hidden Imam” took shape.

It states that Muhammad ibn al-Hasan was the Mahdi—the Messiah—and will return at the end of times. Modern spiritual leaders of the Shiites are considered deputies of the Hidden Imam. Shiites make up about 10% of all Muslims worldwide and are predominant in Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Bahrain.

Sunnis, who are opponents of the Shiites, make up just under 90% of all Muslims. The last Sunni Caliph was King Hussein ibn Ali al-Hashimi of Hejaz, who took the title in 1923. Almost literally, he became a Caliph for an hour, as he was overthrown in 1924.

Within both Shiism and Sunnism, there are different schools. Moreover, in Islam, there is a special mystical trend—Sufism. Sufis, who strive to come closer to God through special spiritual practices, can be either Sunnis or Shiites. The name Sufism likely comes from the Arabic word “suf”—wool, from which clothes worn by Muslim mystic ascetics—Sufis—were made. In Sufism, the role of a mentor—Sheikh—is very important, and his students—Murids—follow his example and guidance.

Sufi orders—Tariqas—developed in the 11th–12th centuries, each with its own practices and distinguishing signs. Around the same time, a unique Sufi philosophy took shape, which found expression, among others, in the poetry of Omar Khayyam, Umar ibn al-Farid, and others. The outstanding Sufi thinker of the 13th century, Ibn Arabi, in his book “The Meccan Revelations,” pondered that all religions contain an element of faith in the One God, but only a Sufi worships God in His entirety.

What are the Duties of Muslims?

The five fundamental principles, or pillars, of Islam trace back to the Prophet Muhammad and are known from the Islamic tradition — the Sunnah. They are called pillars because they form the foundation of Islam.

Another duty for a Muslim is Jihad (Arabic: “effort”), which does not necessarily mean a holy war for the spread of Islam but can also refer to any struggle for faith, such as against one’s own sins.

What Are Sharia and Adat?

Sharia — Islamic law based on the Quran and Sunnah — encompasses all aspects of Muslim life: family and criminal law, doctrine, religious rituals, and ethics. Islam does not distinguish between secular and religious spheres of life, so the legal system of most Muslim countries is based on Sharia.

In some Muslim communities, there are also pre-Islamic local customs — Adat. Sometimes these customs — such as blood feuds, female circumcision, or bride kidnapping — contradict Sharia norms. Islamic scholars have fought against Adat, but this struggle has often been unsuccessful, and the norms of Adat and Sharia have influenced each other. Some forms of Adat have disappeared over time, but others continue to play a significant role in various Muslim regions, particularly in the Caucasus.

How Is a Mosque Organized?

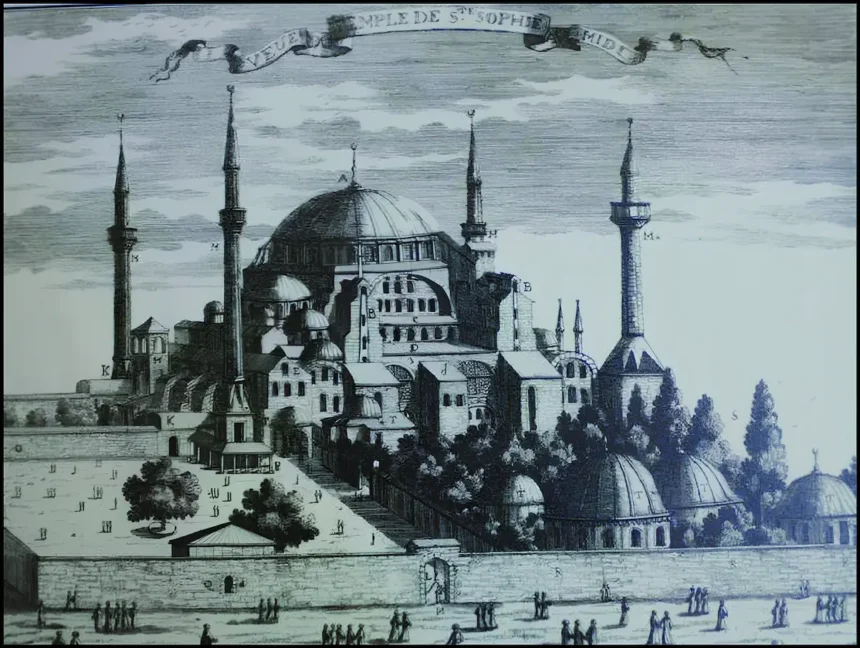

Mosque buildings are architecturally diverse, but there are essential elements: typically, every mosque has one or more minarets — towers from which the call to prayer is announced five times a day. During the Islamic conquests of Christian countries, Christian churches were converted into mosques by adding minarets (consider, for example, the Hagia Sophia, converted into the Aya Sofya Mosque in Istanbul).

Inside, the prayer hall of a mosque always contains a special niche in the wall — the mihrab — which indicates the direction of Mecca for worshippers. Believers must enter the mosque after performing ablution and removing their shoes. Women and men pray separately. The duties of a religious leader are performed by a mullah (Arabic: “master”).

Are Images Forbidden in Islam?

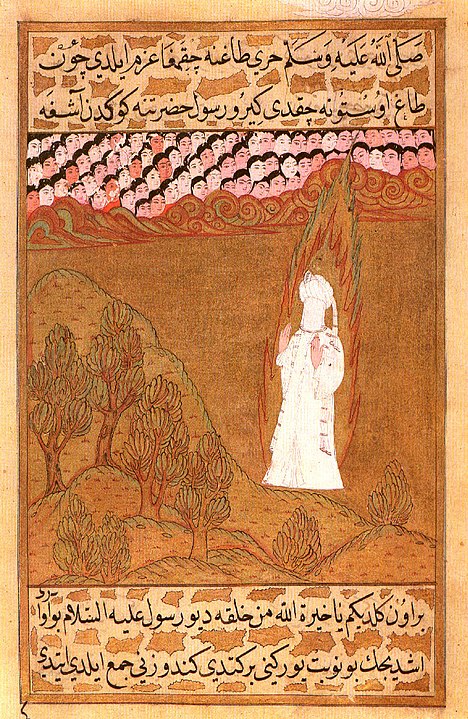

It is a widespread belief that Islam prohibits images of people and animals. However, there is no such prohibition in the Quran itself. In the hadiths, it is said that angels do not enter a house where such images are present, and God considers it a sin for someone to create images, akin to trying to emulate the Almighty: “Indeed, those who create images will suffer torment on the Day of Judgment. They will be told, ‘Bring to life what you have created.'” In one Muslim parable, the sage Ibn Abbas was asked, “Can I draw animals?” He replied, “You can, but remove their heads so that they do not resemble living beings, or try to make them look like flowers.”

In some Islamic regions, such as Iran and Central Asia, people and animals have traditionally been depicted in book miniatures illustrating famous poetic works or historical texts. A striking example is Persian miniatures, where images of not only ordinary people but even the Prophet Muhammad can be seen. These miniatures were considered sufficiently abstract not to contradict the ban on realistic images.

In Arab countries, where the prohibition on images was generally interpreted more strictly, calligraphy flourished — calligraphic images adorn mosque walls and book pages. Nonetheless, a few illustrated Arabic manuscripts depicting living beings have survived to this day.

Regarding photographs, most Muslim theologians permit photography when necessary — for example, for a passport. There is no unified opinion on amateur photography, but even liberal religious authorities recommend keeping family photos in albums rather than displaying them.

What Is Halal?

In a broad sense, halal refers to everything permissible for Muslims; its antonym is haram, meaning “forbidden.” However, in everyday speech, “halal” usually refers to permitted food. Prohibited foods include, for example, pork, as well as the meat of permissible animals (such as beef, lamb, etc.) if they were not slaughtered according to the rules (e.g., strangled, beaten to death, or killed without mentioning the name of God) or died of natural causes.

In Muslim communities belonging to different legal schools, some rules regarding halal food may differ. Additionally, Muslims are forbidden to consume alcohol. In cases of life-threatening hunger, consuming forbidden foods is allowed, but only in the minimal quantity necessary to sustain life.

How Do Muslim Women Dress?

It is easy to notice that the degree of coverage in women’s clothing varies significantly in different Muslim regions. Paranja, burqa, and niqab are designed to completely conceal a woman’s body and face from prying eyes, while the hijab leaves the face uncovered. The tradition of wearing a particular type of clothing is more influenced by local customs than by the prescriptions of the Quran, which are quite general.

For example, in the 24th surah of the Quran (“The Light”), it reads: “Tell believing women to lower their gaze and maintain their modesty. And not to display their beauty; not to dress up or beautify themselves to attract the attention of unrelated men, except for what is obvious. And let them draw their veils over their chests. Let them not display their beauty except to their husbands, relatives, servants, or small children.”

Burkinis, the swimwear that recently caused an uproar in France, were developed in this century by Australian designer Aheda Zanetti, of Lebanese origin, who started producing sportswear for Muslim women under her brand in 2004. According to Zanetti, burkinis are popular not only among Muslim women but also among followers of Judaism, Hinduism, and even some Christian denominations.

What Holidays Do Muslims Celebrate?

Muslims use a lunar calendar, so the dates of holidays shift annually relative to the commonly accepted Gregorian calendar. One of the main holidays is the Feast of Sacrifice, known in Russia by its Turkic name, Kurban Bayramı. On this day, Muslims sacrifice animals in memory of the prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) and his willingness to sacrifice his own son to God.

The Feast of Breaking the Fast (in Turkic, Ramazan Bayramı or Şeker Bayramı) marks the end of the fasting month of Ramadan. Muslims believe that on the 27th night of Ramadan, known as the Night of Destiny, God decides the fate of every person. It is believed that it was on this night that Muhammad received the first divine revelation. In addition to the general Islamic holidays, Shiites also celebrate the birthday of Imam Ali and some other dates.

How Do Muslims View Other Religions?

In the Muslim tradition, all people are divided into the faithful (Muslims), People of the Book, who should not be forcibly converted to Islam, and polytheists, who must be converted to Islam. The People of the Book originally included Jews and Christians because they were also given Revelation (although over time, they distorted it).

Later, during the Islamic conquests, the status of “dhimmi” (Arabic: “protected people”) was also granted to Mandaeans, Zoroastrians, Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and others. The Muslim government allowed the dhimmi to freely practice their faith on the condition of paying a special tax and maintaining loyalty to Muslims.

Over time, the list of dhimmi obligations expanded: they were required to wear distinctive clothing, were prohibited from raising pigs, holding noisy religious processions, and so on. Some restrictions could be temporary—introduced and lifted in different regions. Today, in most Muslim-majority countries, people of different religions are equal before the law.