Glaive at a Glance

What is a glaive?

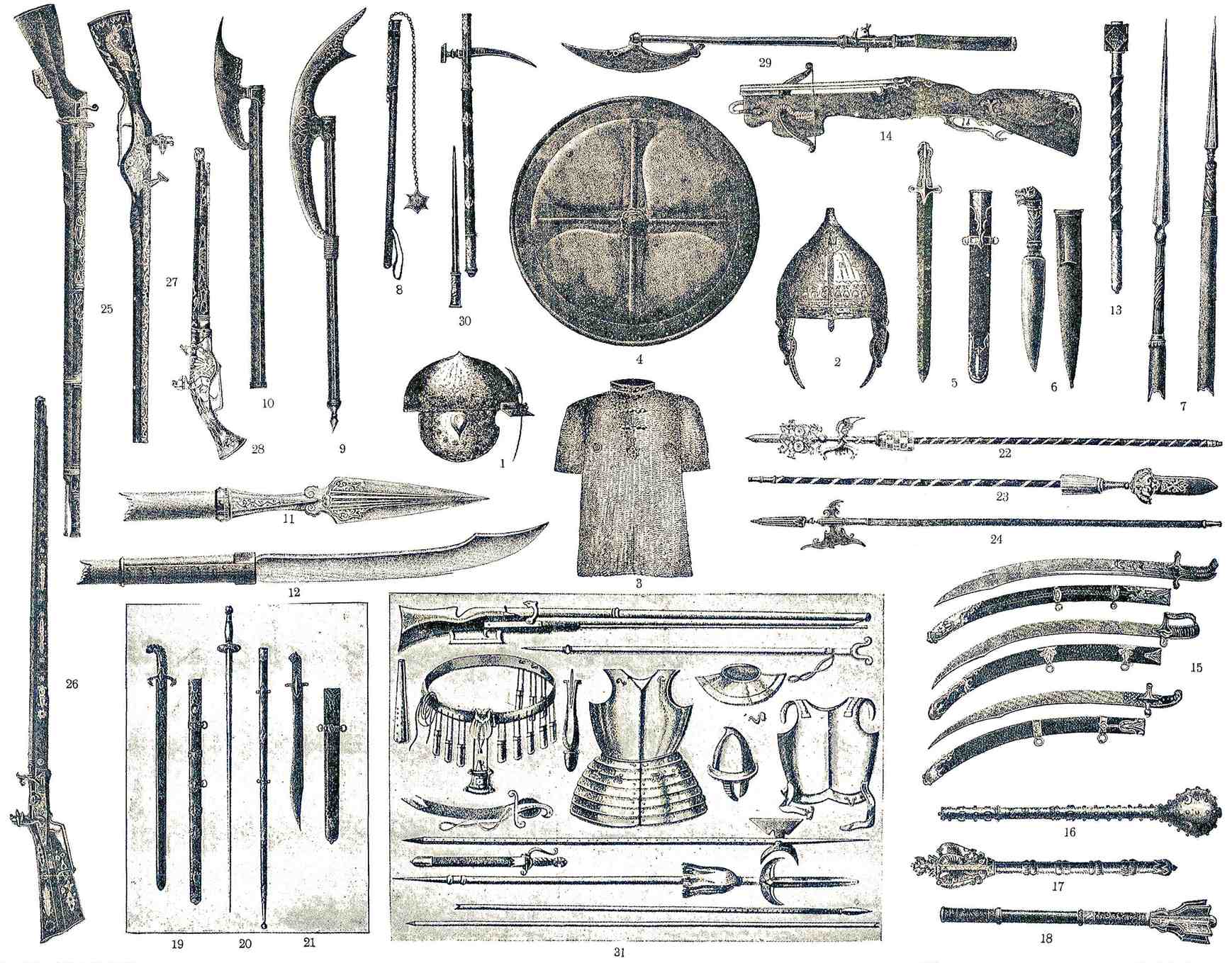

A glaive is a European polearm used in close combat by heavy infantry. It is made of a wooden pole between 4 to 5 feet long with a spearhead of 1.3 to 2 feet long and 2 to 2.8 inches in width. The tip of the glaive is a single-edged blade in the shape of a broad falchion. It also has a spike at the butt of the blade, which serves to grip the enemy’s weapon when reflecting an overhead blow and inflict more effective thrusts against opponents wearing armor.

What is the history of the glaive?

The glaive was first developed from the war scythe between 1200 and 1400. By the 14th century, it had evolved into a genuine weapon, crafted by expert weaponsmiths. At this time, the glaive had been carried as a personal weapon, most notably by crossbowmen. It was a weapon of the palace guard up until the 18th century when it fell out of use. Originally a weapon of battle mainly in the 15th century, the glaive was later adopted as a symbol of nobility in royal courts and by the bodyguard of the Doge of Venice from the 16th through the 18th centuries.

What are the different versions of glaive?

A glaive can have a wide, axe-like point at one end and a simple ball-shaped counterweight at the other. From the butt of the blade, sometimes a spike is laid parallel or directed at a small angle to the blade. The lowest portion of the glaive’s pole also features a spike called a u0022spuru0022 or u0022heel,u0022 although this piece is often not sharpened but pointed. Glaives with heraldic ornamentation, such as coats of arms or seals, can help historians place them in a certain time period.

The glaive is a bladed close combat weapon used by heavy infantry. This European polearm consists of a wooden pole of between 4 and 5 feet (1.2 and 1.5 meters) with a spearhead measuring between 1.3 and 2 feet (40 and 60 cm) in length and 2 to 2.8 inches (5 to 7 cm) in width. In order to make the spearhead sturdier, it is often coated with rivets or wound with a metal ribbon. The weapon weighed around 4.5 to 7.7 lbs (2 to 3.5 kg). The tip of the glaive is a blade, and it is a single-edged blade in the shape of a broad falchion. Occasionally, a hook was made at the other end of the blade to pull a horseman off a horse.

From the butt of the blade, sometimes a spike is laid parallel or directed at a small angle to the blade, serving to grip the enemy’s weapon when reflecting an overhead blow, and also to inflict more effective thrusts against opponents wearing armor (as opposed to slashing blows delivered by the blade’s tip). The glaive, however, is still best used for stabbing attacks.

For balance and to finish off the wounded, the lowest portion of the glaive’s pole also features a spike (called a “spur” or “heel”), although this piece is often not sharpened, but pointed. The glaive existed from about the 14th to the 20th centuries as a unique cold weapon.

Glaive’s Etymology

The term “glaive” comes from French. However, the name either originates in the Celtic word “cladivos”, which means “sword,” or the Latin word “gladius” for the same thing. All glaive allusions in early English and French, however, actually relate to spears.

From the 15th century on, the word “glaive” began to refer exclusively to this specific type of weapon in English. In this century, the term began to be used in its modern sense. Around the same time, glaive became a poetic shorthand for any kind of sword. This is still the most common way the term is used today in French.

History of the Glaive

Glaive bears a resemblance to the naginata of Japan, the guandao of China, the woldo of Korea, and the sovnya of Russia. Among them, the guandao is said to have been invented in the 3rd century AD.

Swords and falchions with long poles gave inspiration to the first glaive designs. And between 1200 and 1400, the first glaive is believed to have been developed from the war scythe. (The word “falx,” which means “scythe” in Latin, is where the name “falchion” originates.) The war scythe was already in use by the Balkan and Mesopotamian populations in ancient times.

In the European Middle Ages, the glaive stood out as one of the most unusual polearms to emerge. The small, single-edged sword was placed on a large wooden shaft that was taller than the wielder.

By the 14th century, it had evolved into a genuine weapon, crafted by expert weaponsmiths. At this time, the glaive had been carried as a personal weapon, most notably by crossbowmen. It proved effective as a weapon against mounted attackers due to its long reach.

It was a weapon of the palace guard up until the 18th century, when it fell out of use. The fact that it was originally a peasant instrument, however, was never forgotten, and it made its way into textbooks as early as 1612:

“GLAIVE. A hooked polearm, resembling a scythe, with a spike on the straight part of the shaft. It may not be very different from the harpe of the Latins or the ἄρπη of the Greeks.

Vocabolario Degli Accademici Della Crusca, Florence 1612, p. 320.

Originally a weapon of battle mainly in the 15th century, the glaive was adopted as a symbol of nobility in royal courts and by the bodyguard of the Doge of Venice from the 16th through the 18th centuries. Glaives with heraldic ornamentation, such as coats of arms or seals, help historians place them in a certain time period.

The glaive used by the palace guard during the reign of Emperor Ferdinand I, for instance, had the imperial monogram on both sides. The Habsburg and Bohemian/Hungarian coats of arms are shown underneath the imperial crown, intertwined with the Golden Fleece Order. This weapon survived into the 20th century through the efforts of the Bavarian court and the Hungarian royal guard.

The Different Versions of Glaive

A glaive might have a wide, axe-like point at one end and a simple ball-shaped counterweight at the other, or it could have two similar double-edged, thin, long blades at both ends. On the other hand, the ones with two blades (one at each end of the pole) are an incredibly unusual variant.

The Chinese developed glaives with three blades, each of which could be used independently of the others. This long blade had two handles so that the glaive could be struck from either end. The third blade was placed between the handles.

In total, about a hundred different alterations of the glaive have been discovered to this day. The weapon is most similar to the halberd (German), bardiche (Austrian), and voulge (French), with the naginata (Japanese), guandao (Chinese), bhuj (Indian), sovnya (Russian), and palma (Siberian) being plausible alternatives.

Glaive in Popular Culture

Guan Yu’s Weapon

Guan Yu (160–220 AD), a Chinese warlord from the Three Kingdoms period, was almost always seen brandishing a glaive, which was known as guandao, yanyuedao, or dadao. He was a Chinese military general famous for his glaive which supposedly weighed 82 catties (about 50 kg or 110 lbs). His weapon went by the moniker Green Dragon Crescent Blade.

In the “Avengers”

Avengers: Infinity War featured a powerful version of this weapon for a villain. This picture shows Corvus Glaive’s weapon during the filming. It can pierce Vision’s Vibranium armor, deflect his Mind Stone-fueled energy shot, and disperse the sonic waves from Shuri’s Vibranium Gauntles.

When the Glaive Became a Throwing Weapon

For some reason, the term “glaive” has also been used to describe a fantastical multi-edged throwing weapon since the 1980s, conceptually similar to but bigger than the Japanese ninja shuriken.

Such weapons are often given the capacity to “bounce back” to the thrower, either magically or through the boomerang concept. Fantasy novels and movies (like Krull from 1983, which has a five-pointed glaive) as well as video games (Dark Sector, Torchlight 2, Warframe, and Dungeon Siege II) depict characters who throw glaives.

In the “Keeper of Swords”

Nick Perumov’s “The Keeper of Swords” (not released in English) has a protagonist named Ker Laeda, also known as the warrior of the Grey League of Fess, also known as the necromancer “Neyasynth”. And he favors the glaive as his primary weapon.

Ker Laeda’s glaive is still not emblematic of the weapon as a whole. It has two blades (or cutting points), which makes it a double-edged pole. It is also much shorter and lighter than the real weapon, which is not designed for delicate swordwork.

Unlike other long-bladed weapons, Ker Laeda has no trouble wielding it in underground environments like tunnels. Plus, a hefty, long glaive has little chance of stopping an arrow shot at point-blank range. Ker Laeda’s weapon is also detachable, in that it turns into two swords.

Many people, inspired by Nick Perumov’s work, incorrectly assume that glaives always have two blades, despite the fact that weapons with blades on both ends of the pole are very rare.

References

- Decorative glaives – Arkela – Alamy

- Vocabolario Degli Accademici Della Crusca, Florence 1612, p. 320.

- Medieval Weapons: An Illustrated History of Their Impact – Kelly DeVries, Robert Douglas Smith – Google Books