King of Navarre and leader of the Huguenots during the Wars of Religion, Henry IV became King of France in 1589. The first sovereign of the Bourbon dynasty, he worked to pacify the kingdom (Edict of Nantes) and restore the authority of the monarchy, which had been weakened by civil war. Surrounded by capable ministers like Sully, Henry IV reorganized the Kingdom of France: the economy, finances, agriculture, and commerce were revived.

Everything was undertaken to make France a prosperous kingdom, reconnecting with artistic, cultural, and urban development. It was also during his reign that exploration and colonization of Quebec were reignited, with Samuel Champlain’s expeditions along the Saint Lawrence River. His assassination by Ravaillac on May 14, 1610, forged the legend of the “king with the white plume” and established him in popular imagery as one of the just and good monarchs.

Summary of Key Achievements

Henry: Child King of Navarre

Born on December 13, 1553, Henry of Navarre was, in a way, an upstart, a “peasant from the Pyrenees,” a “Béarnais”—a king of operetta, caught between Spain and France. Yet, he was also the first prince of the blood, directly in line for the French throne as he was a descendant of Saint Louis through his father Antoine de Bourbon. From his childhood, after being raised in the fresh air of Béarn by his mother Jeanne d’Albret, he became a political pawn and was sent to the French Valois Court. He became a political hostage, a guarantee of alliance between the two kingdoms.

At the end of the 16th century, no one would have bet on the extinction of the ruling Valois line. Henry II, the son of Francis I, had numerous offspring with his wife, Catherine de’ Medici. However, this new generation would disappear, throwing the crown into a dark dynastic battle from which France would emerge exhausted.

The Rival of the Valois

At first, nothing foretold the future destiny of Henry IV. A scion of two illustrious families that had embraced the Reformation, this prince of the blood initially appeared, in the France of the Wars of Religion, as the natural leader of the Protestant party. A leader whose influence also rested on vast personal domains: those of the Albret family in the southwest, with the royal title of Navarre in Béarn, and those of Bourbon-Vendôme in the Loire Valley. His youth was marked by the political confusion that prevailed during the early wars.

Raised at the French court alongside his royal cousins, he nevertheless took part in Protestant military campaigns in 1567 and 1569. Three years later, as the newly married King of Navarre to the dazzling Marguerite de Valois, he escaped the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre by renouncing Protestantism. In 1576, at the age of 23, he fled from Paris, where he had been held semi-captive as a political hostage, to regain his Reformed faith and contest with Condé, his relative, for leadership of the Huguenot party.

Allied with the king’s intriguing brother and his discontented Catholic friends, he appeared at that time as a great feudal lord, taking advantage of the circumstances to expand his personal authority. It was only after the death of Monsieur (the king’s brother) in 1584, which designated him as the future King of France, that events gradually revealed his statesmanship. In the War of the Three Henrys, the Béarnais fought to assert his rights but always strove, even against King Henry III, to appear as a defender of the public good rather than a party leader, at the risk of displeasing some of his fellow Protestants.

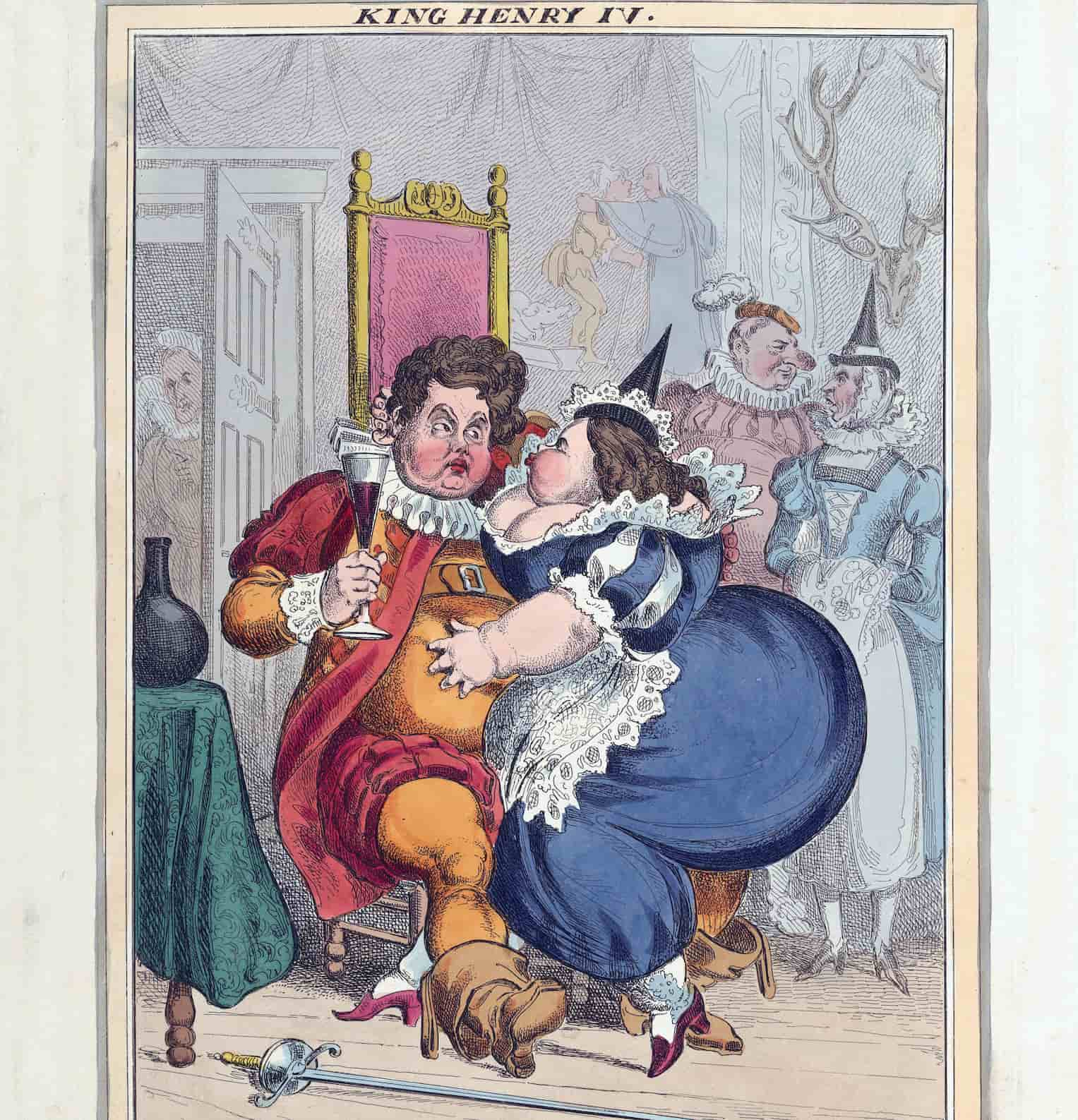

Henry IV: War, Love, and Versatility

Henry spent more time in the saddle than on the velvet of a throne. The rather Spartan military training of his youth served him well.

As leader of the Huguenots from 1569, during the La Rochelle assembly, he waged open war against the King of France. However, lacking heirs and threatened by the rising power of the House of Lorraine and the Guises, Henry III sought rapprochement with Henry of Navarre.

Henry III barely had time to have the Duke of Guise assassinated before he fell to the dagger of the monk Jacques Clément. As the designated heir, Henry IV would need to be patient to reconquer the throne of France starting in 1589. Cunning and strategic, these qualities made him a feared and respected war leader. Only Paris proved a real challenge, as the city, fanatical under the influence of monks and the Catholic League, only surrendered when he converted to Catholicism and was recognized as king in 1594.

His religious versatility could be seen as political opportunism. As a child, his mother Jeanne d’Albret initiated him into Calvinism. However, Henry IV was never to be Saint Louis and held a certain detachment towards religion that allowed him great tolerance. His numerous conversions and switches between Catholicism and Protestantism are well-documented. His Protestant supporters were quite displeased with his conversion in pursuit of the French crown. Nevertheless, he issued the Edict of Nantes on April 13, 1598, converted to Catholicism, and thus managed to temporarily resolve the issue of the Wars of Religion.

This versatility extended to his relationships with women. Politically married to Marguerite de Valois, Henry IV was a prisoner of his passions and could not help but make promises, including marriage, to various lovers—such as Gabrielle d’Estrées. However, Henry was already married and embarked on a long process of separation from Margot. Imprisoned and in exile, the Valois heiress refused to cede her place to scheming adventurers, doing everything possible to delay the process. She ultimately agreed to step aside for Marie de’ Medici, the “banker’s daughter.”

France in 1598

After forty years of crisis and civil war, France found itself in deep material and moral disorder. The demographic bloodletting was particularly serious because it was accompanied by economic ruin. The constant movement of soldiers ravaged the countryside. In certain provinces, farms and villages were half-deserted, fields left untended, livestock destroyed, and famine loomed. Cities were overcrowded with refugees, unemployed people, the sick, and the roads were filled with vagabonds, beggars, and soldiers turned bandits.

While the common people suffered greatly and the lesser nobility likely lost more than they gained from the turmoil, the high aristocracy benefited significantly, and the financiers made handsome profits. However, the biggest winner was the legal bourgeoisie: as the main support of the third party, which ultimately imposed a compromise solution in the name of public good, they gained a sense of class consciousness and an enhancement of their social prestige.

The monarchy as an institution emerged significantly weakened from the crisis. The kingdom was fractured. Cities, divided between factions, had grown accustomed to and enjoyed self-administration. Entire provinces, in the hands of governors who had become all-powerful during the troubles, escaped the king’s authority. Financially, the monarchy was in dire straits. Under Henry III, taxes had risen considerably, but they were not being collected, either because people refused to pay or because the money, intercepted in the general anarchy, never reached the treasury. Officials, feeling they had a greater sense of public duty than the monarchy, were tempted to increase their role in the state, and parliaments sought to control the functioning of institutions.

A clear sign of the weakening royal power was the need to convene the Estates General on four occasions (1560, 1576, 1588, and 1593) after not having been called since 1484. A theoretical challenge to absolutism emerged. Protestants, as early as 1573, had proclaimed the right of subjects to rise against a tyrannical sovereign. Among the ranks of the Catholic League, there were theorists of tyrannicide who legitimized the murder of a king when he failed to uphold his coronation oath to defend the Catholic faith.

The Work of Henry IV

Upon taking power, Henry IV first decided to reunite Navarre with France, a union that would be formalized during the Revolution. However, his most urgent task was to reassure his former Huguenot coreligionists and establish peaceful coexistence between the two faiths. The Edict of Nantes (1598) granted Protestants civil equality, full freedom of conscience, regulated their worship, and provided significant political privileges, including mixed chambers of justice and about a hundred fortified towns as “places of safety.”

This solution made Protestantism just another particularism among many in the vast mosaic of particularisms and privileges that constituted Ancien Régime society. The Huguenots gained a legal status, but Protestantism risked losing its soul: confined in a legal framework, it became demobilized and dormant just as the fruits of the Counter-Reformation were giving rise to a renewed, dynamic, and militant Catholicism.

With peace restored among the French, Henry IV turned to rebuilding the kingdom. Through a skillful mix of firmness and leniency, he restored royal authority over the feudal lords, provincial estates, and urban communities. Marshal Biron, a former companion-in-arms who conspired with Spain, was executed in 1602, and the ever-conspiring Duke of Bouillon was forced to submit in 1606. But until the end of his reign, the king continued to battle the legalism of the magistrates, seeking to curtail the powers of parliaments and other sovereign courts. Prudent financial management and indirect taxation, under the supervision of Sully, allowed for a moderation of the taille (direct tax) and the accumulation of a significant royal treasure at the Bastille. However, Sully’s economic achievements were likely overestimated.

As a country gentleman, Sully primarily promoted agriculture and, as a grand surveyor, sponsored large public works projects (roads, bridges, canals, etc.). Meanwhile, Barthélémy de Laffemas laid the groundwork for industrial and commercial mercantilism, which, systematized by Antoine de Montchrestien in 1615, would inspire the economic thought and actions of Richelieu and later Colbert. In Paris, significant urban planning projects were undertaken, such as the development of the Marais district, the Place Royale (now Place des Vosges), the Pont-Neuf, and the Place Dauphine. Architectural achievements continued the Valois tradition at the Louvre, the Tuileries, Fontainebleau, and Saint-Germain.

Externally, the Béarnais king continued the anti-Habsburg policy of his predecessors. In 1601, he forced Savoy, Spain’s traditional ally, to cede Bresse and the Pays de Gex. Although he was unable to prevent the United Provinces from signing the Twelve Years’ Truce with Spain in 1609, he took advantage of every incident in the Empire to strengthen his alliance with Protestant princes. He was likely on the verge of resuming the war against the Habsburgs when he was assassinated by Ravaillac.

The Legend of “Good King Henry”

On May 14, 1610, in Rue de la Ferronnerie in Paris, Henry IV met his fate with legend. François Ravaillac committed the ultimate crime by assassinating a king consecrated and anointed by God. Although his punishment was widely discussed, Henry IV’s death was met with relative calm in France. By 1610, many French citizens had complaints about the king. The proverbial “chicken in the pot” was not in their dishes every Sunday, and despite his common sense and simplicity, Henry IV was far from being a unifying and beloved figure. Peasant unrest, opposition from both extreme Catholics and Protestants, and other discontent explain the tragic end of the “Green Gallant.”

To be sure, he was appreciated for restoring peace, and his personal qualities made him likable. A fine horseman, bold soldier, and cheerful companion, Henry, like a true gentleman of his time, enjoyed the countryside, hunting, and rural life.

His sturdy rusticity contrasted pleasantly with the refined, somewhat morbid elegance of the last Valois kings. Jealous of his authority, but charming and persuasive, he preferred seduction to coercion. But he had flaws: sometimes careless, often forgetful (of friends and foes alike), and above all, an incorrigible lover. Before and after his remarriage to Marie de’ Medici in 1600, he had countless mistresses, occasionally sacrificing state matters for their sake.

The public criticized the king’s behavior, but they had other grievances as well. The nobility, although beneficiaries of his reign, felt too tightly controlled. Magistrates complained of his authoritarianism, and parliaments, traditional defenders of Gallican Church liberties, hesitated to register both the Edict of Nantes and the concessions made to the Pope and the Jesuits. The common people, who rejoiced at the end of the civil wars in 1598, found by 1610 that taxes were too high, the “chicken in the pot” too rare, and the rumors of war very alarming.

While Protestants accused the king of betraying his faith, many Catholics doubted the sincerity of his conversion. As for the League’s nostalgics, they saw his plans against Spain as a betrayal of Catholicism and glorified tyrannicide. The surest proof of the persistent hostility toward the Béarnais king was the number of plots and assassination attempts he survived before succumbing to Ravaillac’s dagger. But his death, by conferring upon him the aura of a martyr, restored the love of his people and secured his place in legend.