Apothecary or Pharmacist? Around 1260, an “apothecary” was someone who prepared and sold drugs. By 1314, the term “pharmacy” referred to purging with medication. Around 1530, an “apothecary” was often a nun who prepared remedies for the sick in hospices. Then, in 1575, “pharmacy” became the science of remedies and medications. Finally, around 1730, the apothecary’s shop, or pharmacy (both terms were used), was where drugs, remedies, and medications were prepared and stored.

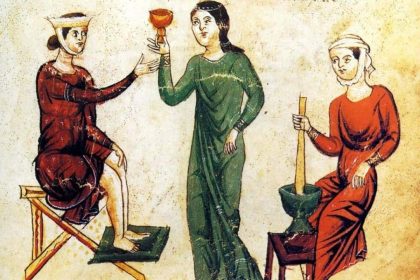

In the 12th century, medicine and pharmacy were still intertwined and often practiced by religious figures. Care was provided in Hôtel-Dieu hospitals, which had a hospitalization room, a botanical garden, and an apothecary. In 1241, at the request of the Germanic Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, the Edict of Salerno imposed an oath on all those who wished to manufacture medicines.

The profession of apothecary was monitored, and the price of remedies was regulated. This edict established a legal separation between doctors and apothecaries. The Edict of Salerno, through its diffusion throughout Christendom, can be considered the birth certificate of the apothecary profession, even though specialists in medication preparation had existed since antiquity.

When the Apothecary Was Still Just A Learned Grocer…

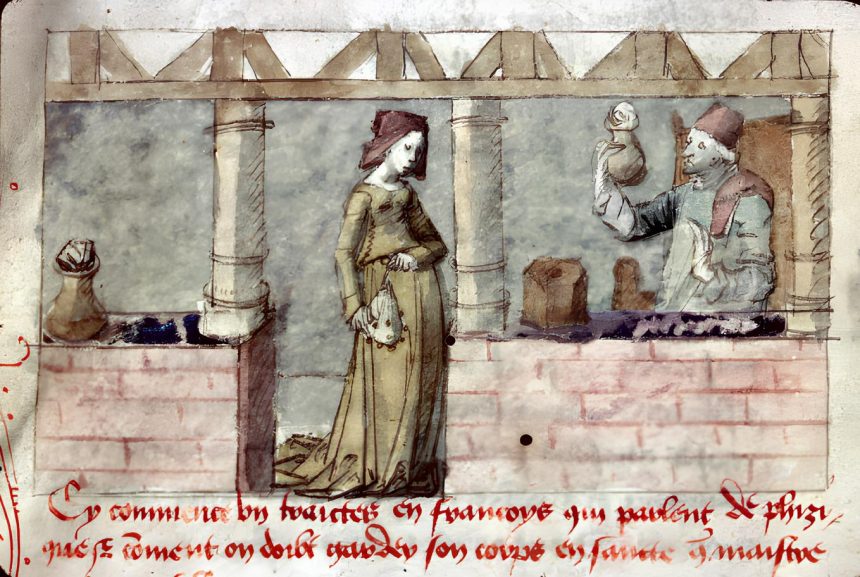

Medieval medical doctrine considered diseases as morbid essences and remedies as antidotes. In the Middle Ages, apothecaries and grocers sold the same types of products: plants, spices, and especially sugar, which was rare and considered more of a remedy than a food.

Apothecaries therefore belonged to the grocers’ guild. Their training was exclusively practical and focused on learning how to prepare remedies. Master apothecaries were responsible for instructing apprentices, who needed to have a basic knowledge of Latin and grammar to read doctors’ prescriptions. The duration of apprenticeship varied according to local legislation; in Strasbourg, the training of an apothecary’s assistant lasted five years.

Birth of the Apothecary Profession

Apothecary guilds were formed in cities, giving rise to the regulated nature of modern pharmacy. In the Kingdom of France, the first apothecary statutes appeared in Montpellier at the end of the 12th century, then in Avignon in 1242, Paris in 1271, and Toulouse in 1309. In 1484, Charles VIII issued an ordinance stating that “henceforth no grocer in our said city of Paris may engage in the business and vocation of apothecary unless the said grocer is himself an apothecary.”

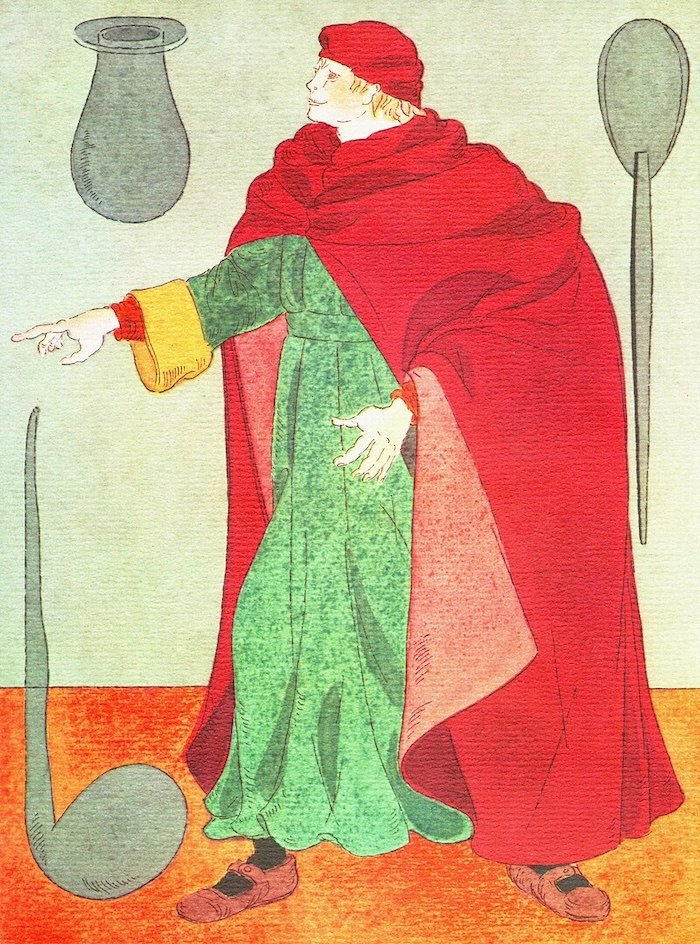

Many conflicts arose over questions of competence between trades; apothecaries also found themselves in competition with barber-surgeons. By the 16th century, apothecaries, as members of an influential guild and holders of rare and expensive drugs, had become true merchants. The sale of tobacco in powder form was even reserved for apothecaries.

Apothecary Profession Gains Prestige

In the 17th century, science progressed, but remedies extracted from the plant, mineral, and animal kingdoms did not necessarily align with advances in pharmacology. The first public school of “pharmacy” dates from 1576, and in 1777, Louis XVI transformed it into the Royal College of Pharmacy. The king definitively separated the professions of apothecary and grocer and recognized pharmacists’ monopoly on the sale of medicines.

He officialized pharmacy as a medical science, requiring in-depth studies and knowledge. In April 1803, First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte created three pharmacy schools in Paris, Montpellier, and Strasbourg. Each school was required to organize, at its own expense, the teaching of at least four subjects: botany, the history of medicines, pharmacy, and chemistry.

Military Apothecary

In the field of medicine and natural sciences, it is important to emphasize the essential role of military pharmacy: the concern for improving survival conditions and providing care to soldiers and sailors contributed to advances in pharmacology. Military pharmacists were involved in all campaigns and expeditions on land and sea. Witnesses to the mass casualties on battlefields and the ravages caused by diseases and malnutrition, they became responsible for the manufacture and distribution of health and hygiene products to the armies.

The presence of apothecaries associated with the king’s armies is first described in a report by the surgeon and anatomist Ambroise Paré in 1552. Richelieu created the first sedentary hospital for soldiers in Pignerol (in Italy) in 1620, staffed with two apothecaries. They were associated with doctors and surgeons in the military hospitals established by King Louis XIII during the Thirty Years’ War, particularly in Italy in 1629.

The royal edict of 1674 provided for an apothecary position at the Hôtel des Invalides, which received “all officers and soldiers both crippled and old and decrepit” from Louis XIV’s wars. In the 1740s, the increasing abuses in military hospitals led to the formation of a corps of military apothecaries subordinate to doctors, with one apothecary for every fifty hospitalized soldiers.

An Illustrious Apothecary: Antoine Parmentier (1737-1813)

At 20, Antoine Parmentier was already an army pharmacist during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). Taken prisoner in Germany, he discovered the nutritional quality of the potato, which was used as food for animals and prisoners. In 1766, Parmentier obtained the position of apothecary at the Royal Hôtel des Invalides and continued his agronomic research on potatoes.

In 1772, members of the Paris Faculty of Medicine finally declared that potato consumption posed no danger to health. With the support of Louis XVI, Parmentier created a plantation in Neuilly in 1786, and then in Gentilly, where the guards were ordered to let the population “steal” the precious plants, helping to popularize the tuber.

Parmentier also focused on the preservation of flour, wine, and dairy products. He improved the quality of bread distributed to armies and hospitals by devising a new bread-making method that gave rise to the reputation of French bread.

He advocated for the preservation of meats by refrigeration and worked on the technique of food canning by boiling, developed by Nicolas Appert in 1810. Parmentier became the first president of the Paris Pharmacy Society and was very attached to his title of pharmacist. He defined his life and work thus: “My research has no other goal than the progress of the art and the general good… I have written to be useful to all.”