The recognized modern form of European theater began to evolve in the 16th century as the range of play subjects broadened to appeal to a wider audience and the number of spectators increased. This development coincided with playwrights, designers, and actors venturing beyond the confines of church boundaries. Itinerant actors showcased their talents in palaces, noble homes, and universities as well as in the green spaces of villages and city squares.

- History of Modern Theater in Europe

- Upstart Crow: Shakespeare’s Rising

- Theaters of Mystery and Miracle Based on the Bible

- University Wits: The Era of University-Based Theater Writers

- Puritan Opposition to Shakespeare and Theater

- From Inn-Yard Theatre to Indoor Theaters

- Ben Jonson: Festivities, Music and Murder

- Richard Burbage and William Kemp: Stars of the Elizabethan Era

- Le Cid: The Beginning of French Drama

- Playwrights of Spain’s Golden Age

- Louis XIV’s Theater Revolution

- Commedia dell’arte

History of Modern Theater in Europe

In this new genre of theater, alongside the legendary stories of kings and queens, everyday subjects such as jealousy between spouses, competition among villagers, and the sometimes amusing, sometimes bitter relationships between masters and servants were also narrated.

Playwrights like Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Ben Jonson, who were associated with reputable theater companies, were responsible for the transformation during the Elizabethan era in England.

In the late 16th century, the first permanent theaters, which were open-air theaters, were constructed in London. Subsequently, during the reigns of King James and King Charles I, indoor theaters were built.

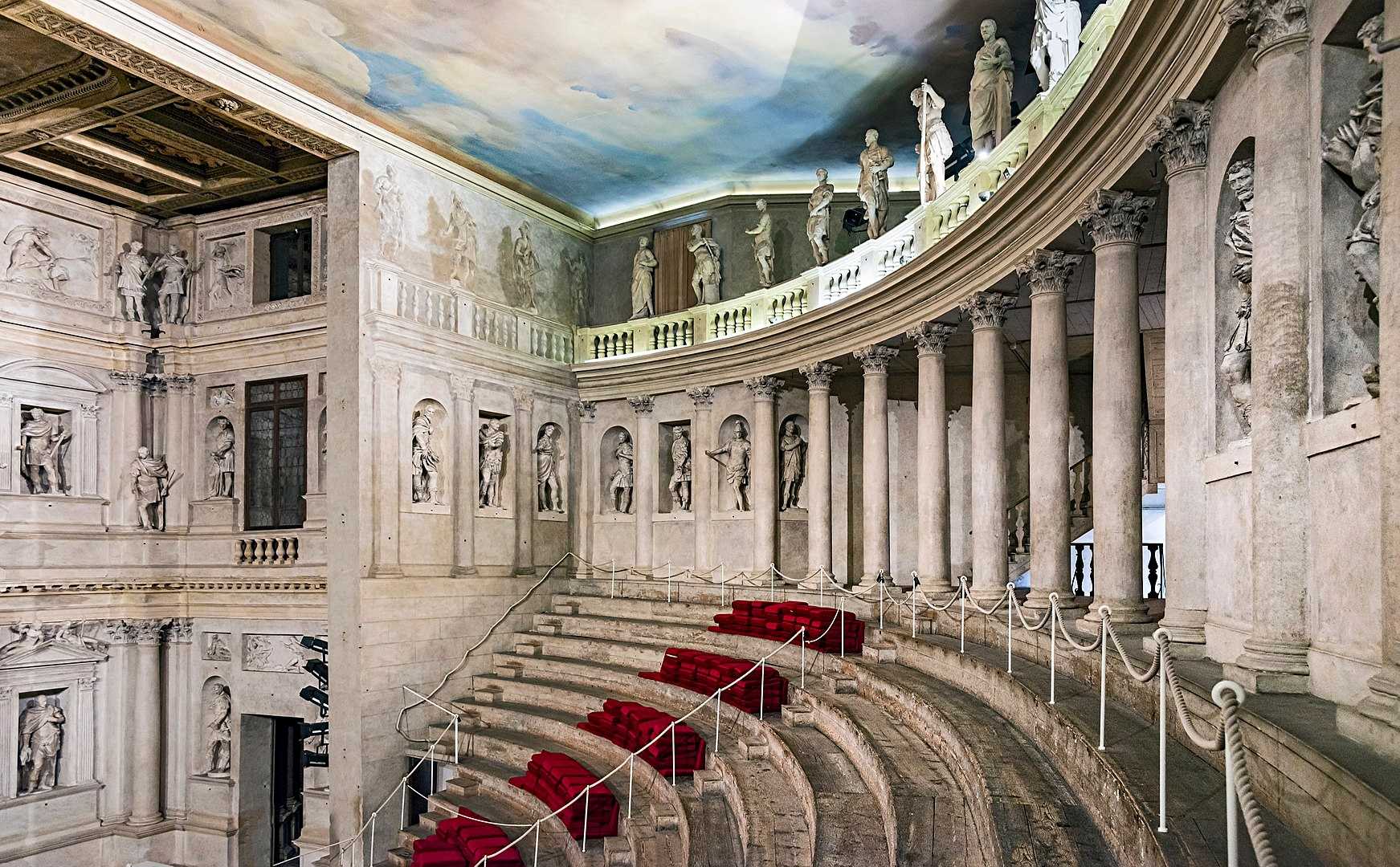

Italian models, particularly those by Andrea Palladio, who built the Teatro Olimpico (“Olympic Theatre”) in Vicenza in 1580 as a recreation of the ancient Roman era, had an influence on architects.

In England, Inigo Jones, in France, Giacomo Torelli, and in Italy, Nicola Sabbatini, developed finely crafted lighting effects and movable stage sets for these venues. These innovations paved the way for playwrights, actors, and directors across Europe to have ownership in the theaters where they worked or where their plays were performed, allowing them to have more control over their productions.

Upstart Crow: Shakespeare’s Rising

Shakespeare masterfully crafted the intricate plots and vivid characters of his plays by weaving together a tapestry of knowledge derived from extensive reading and research. His sources of inspiration spanned a diverse spectrum, showcasing his remarkable breadth of influence.

When delving into English history, he drew upon the wealth of information found within Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles, a contemporaneous historical compilation. This rich historical backdrop provided the foundation for many of his historical plays, lending them an air of authenticity and depth.

Intriguingly, the allure of ancient Rome captivated his imagination, leading him to the works of the Greek biographer Plutarch. Through Plutarch’s writings, Shakespeare unearthed a treasure trove of stories and characters that he skillfully adapted into his plays set in the heart of the Roman Empire.

Shakespeare was no distant observer; he was immersed in the bustling world of the theater. His successes and achievements within this realm did not go unnoticed, eliciting both admiration and envy from his contemporaries.

A testament to the competitive milieu of the theatrical landscape, in 1592, his rival playwright Robert Greene famously coined the phrase “an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers” to describe Shakespeare, shedding light on the fervent rivalry and ambition that fueled the dramatic arts during that era.

Theaters of Mystery and Miracle Based on the Bible

The roots of theater can indeed be traced back to the vibrant cultural shifts of the late 12th and 13th centuries, a period marked by a gradual departure from the confines of Latin-speaking churches. As communities sought to infuse their spiritual and ceremonial performances with a more relatable and accessible essence, the streets became an open canvas for their expressive narratives.

In France, the emergence of grand ceremonial plays, known as “mystery” and “miracle” plays, captured the collective imagination. These dramatic spectacles drew inspiration from the Bible, skillfully weaving together tales that brought to life the profound events of the lives of saints. It was an immersive journey into sacred stories, a communal experience that resonated with audiences at the time.

Beyond France, the enchantment of “miracle play cycles” (the earliest formal plays in Europe) extended to Northern England, where their allure spanned multiple days. With the assistance of various guilds, performers moved their mobile stages through the town in an itinerant performance that encouraged a lively exchange with the audience, who traveled alongside them.

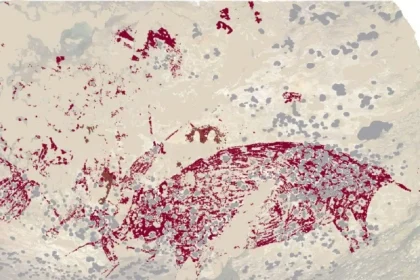

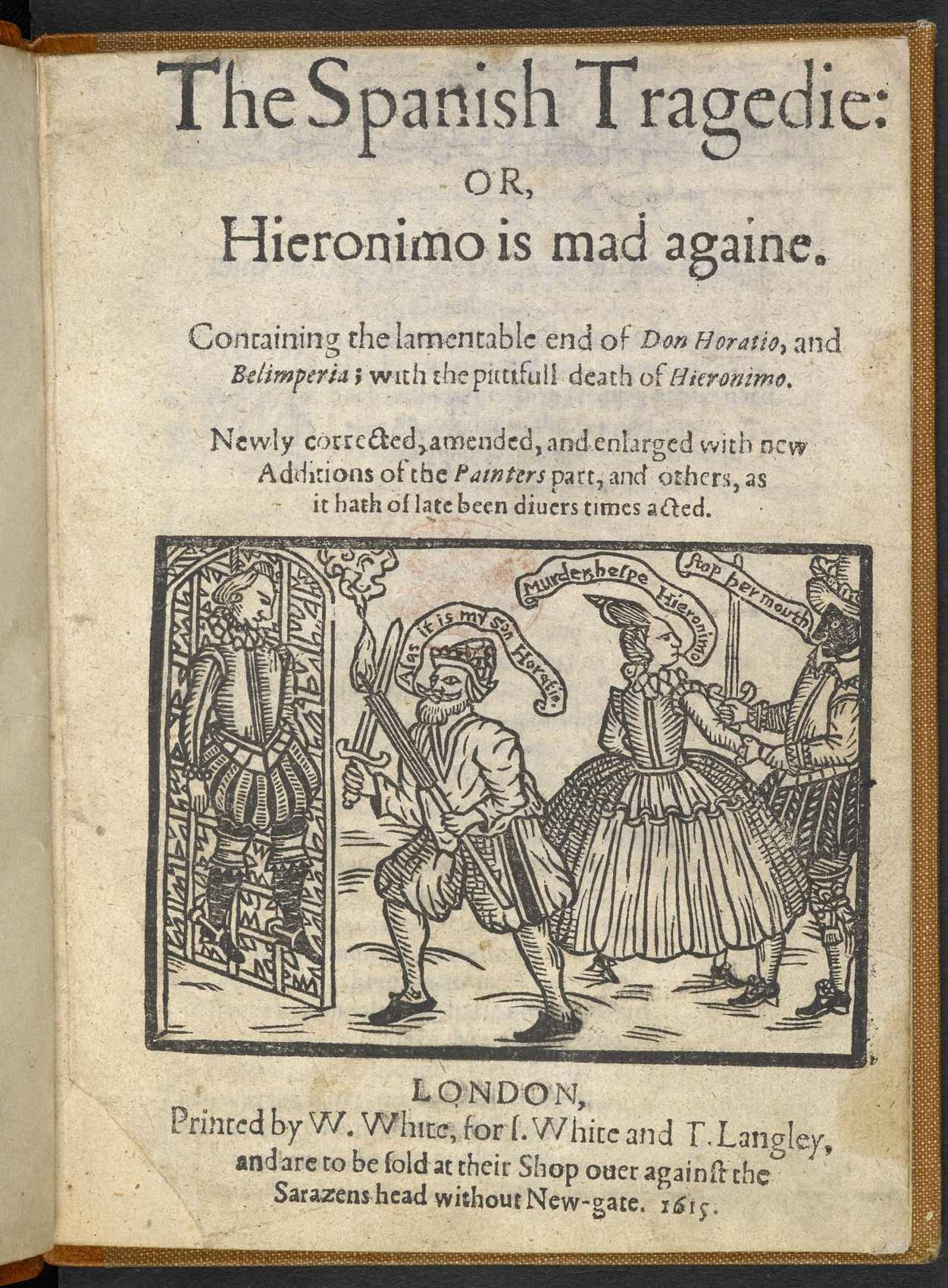

As the theatrical landscape continued to evolve, a new genre emerged in the form of “revenge tragedies.” This genre, harkening back to the works of the classical Roman playwright and philosopher Seneca, held echoes of the medieval miracle plays, albeit with a striking twist. These dramas delved into the realm of torture and bloody events, exploring the darker aspects of human nature.

Among the compelling offerings of this period was “The Spanish Tragedy,” penned by the adept hand of Thomas Kyd in the vibrant hub of London in 1587. This play, with its gripping narrative of a bloody murder, captured the essence of its time, captivating audiences with its intrigue, suspense, and exploration of vengeance.

University Wits: The Era of University-Based Theater Writers

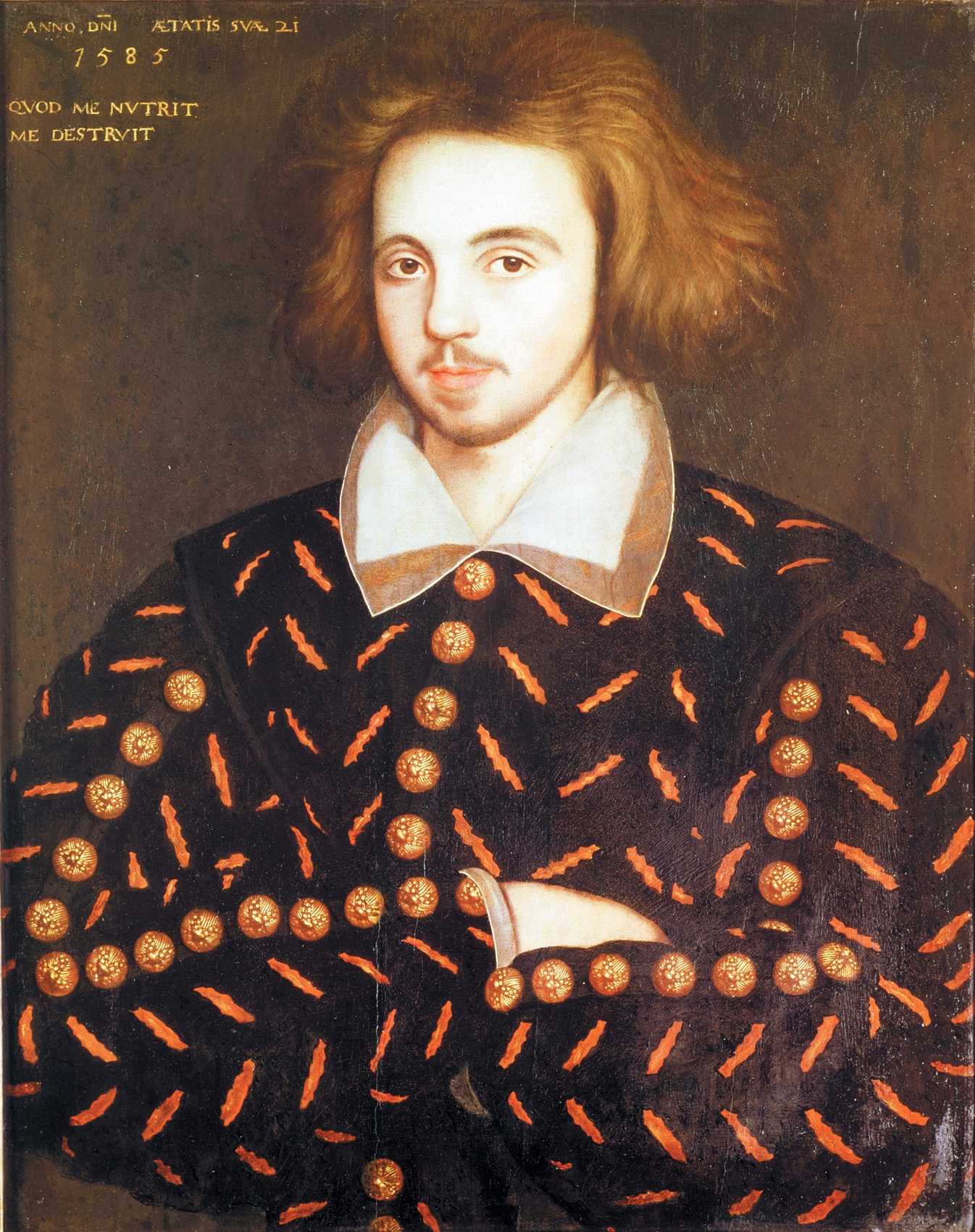

As the late 16th century unfolded, the burgeoning popularity of theater set the stage for a hunger for fresh narratives and new artistic expressions. This insatiable demand found its answer in a group of erudite writers known as the “university wits,” individuals whose intellectual journey had been nurtured within the hallowed halls of Oxford and Cambridge. Among these luminaries, Christopher Marlowe stood tall as a playwright and poet, a maestro whose creations left an indelible mark on the theatrical landscape.

At the forefront of this group, Marlowe wielded his creative quill to craft a series of epic dramas that transcended the boundaries of convention.

Works such as “Doctor Faustus,” “The Famous Tragedy of The Rich Jew of Malta,” “Tamburlaine the Great,” and “Edward II” unfolded on the stage with a newfound sense of dynamism and potency.

Marlowe’s ingenious manipulation of free verse, specifically the unrhymed iambic pentameter known as blank verse, breathed life into his characters and narratives, ushering in a new era of English drama.

Yet, Marlowe’s genius extended beyond mere linguistic mastery; his works delved into the very essence of human existence. Themes of ambition, power, and the intricate interplay of human nature unfurled within the realms of his narratives, engaging the minds and hearts of audiences. Through his craft, Marlowe painted vivid portraits of the human psyche, a testament to his profound understanding of the complexities of the human condition.

Marlowe’s innovative use of blank verse resonated not only within the confines of the theater but also reverberated through the corridors of literary history. His trailblazing contributions reverently carved a path toward the evolution of English drama, igniting the fires of inspiration among his contemporaries and generations to come.

Indeed, Marlowe’s influence on the dramatic tapestry of his era cannot be overstated. His contributions acted as a transformative catalyst, propelling the transition from the age-old tapestry of medieval mystery and morality plays to the intellectually stimulating and artistically sophisticated works that defined the Elizabethan era.

As his ink danced upon parchment and his characters took their strides upon the stage, Christopher Marlowe became a beacon of artistic innovation, casting a radiant light upon the ever-evolving landscape of theater.

Puritan Opposition to Shakespeare and Theater

During the vibrant and culturally rich Shakespearean era, a group emerged whose stance on theater was a stark departure from the prevailing sentiments of the time. This group, known as the Puritans, bore a critical visage towards the performing arts and the hallowed stage.

Shakespeare bravely confronted the objections of the Puritans to theater and tackled a wide range of topics, critiquing oppressive rulers and exploring gender relations (which he highlighted by employing male actors for female roles in those days).

Their disapproval was deeply rooted in a tapestry of concerns that extended beyond mere artistic expression. To the Puritans, theater cast a long shadow, one that they feared could eclipse the moral fabric of society and erode the foundations of religious teachings. In their eyes, the allure of the stage had the potential to tempt individuals down a treacherous path, leading them away from the righteous and virtuous course championed by their beliefs.

The Puritans harbored a profound conviction that theater was a gateway to frivolity, ushering in a realm of entertainment and worldly pleasures that stood in stark contrast to their austere principles. This dichotomy between the allure of the stage and the solemnity of their spiritual convictions fueled their condemnation of theater as a sinful indulgence.

Furthermore, the Puritans perceived a more ominous undercurrent within the realm of theater. They saw it not merely as a spectacle but as a force that could disturb the sanctity of religious practices and disrupt the harmony of social order. The Puritan leaders, in particular, viewed theater as a potential harbinger of moral decay, a corrosive influence that could erode the bedrock of their religious values.

In response to these perceived threats, the Puritans embarked on a quest to curb the influence of theater. Their efforts manifested in various forms, from outright bans to stringent restrictions on the very essence of the art. They sought to extinguish the flickering flames of the stage, believing that by doing so, they could shield their community from the potentially pernicious allure of the theater.

The Puritans’ stance on theater resonated with their broader worldview, one that espoused a fervent commitment to piety, moral purity, and the unwavering adherence to their religious principles. In their eyes, the pursuit of artistic expression on the stage ran counter to these ideals, and as such, they were unyielding in their efforts to curtail its influence.

From Inn-Yard Theatre to Indoor Theaters

In the bustling tapestry of the late 16th century, a new chapter unfolded in the realm of theatrical enchantment with the construction of public theaters that would forever shape the landscape of dramatic expression. These open-air amphitheaters, like the Swan and the renowned Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, stood as emblematic symbols of a burgeoning era of artistic and cultural exploration.

Drawing inspiration from the very heart of communal gathering, these theaters found their genesis in the courtyards of inns that had long been hallowed ground for communal performances. The open-air circular design, reminiscent of the captivating embrace of a courtyard, breathed life into these new bastions of the dramatic arts. In the enchanting circle of the Wooden “O,” the echoes of Shakespeare’s immortal verses reverberated, weaving tales that would endure through the annals of time.

This Wooden O’ is a quotation from Shakespeare’s Henry V, a reference to the shape of the Globe playhouse itself: a round theatre constructed out of oak. Source: Shakespeare’s Globe.

The stage itself, an expansive platform adorned with the mysteries of artistic creation, was a canvas for the convergence of imagination and reality. At its back, a sheltered enclave beckoned—a sanctuary where the unfolding drama could find its secret pulse, hidden from the gaze of eager eyes.

It was a symphony of angles, with seating encircling the platform on three sides, forging an unbreakable bond between performers and audience and bridging the realms of illusion and engagement.

As the theatrical landscape continued to evolve, the next chapter unfolded with the emergence of indoor theaters in the early 17th century. These majestic edifices stood as testaments to the profound changes in both architecture and society.

Within their hallowed halls, the invisible curtain of class was drawn, distinguishing the refined sensibilities of the upper echelons from the open-air performances that had once united the masses.

Ben Jonson: Festivities, Music and Murder

A character with unmatched wit and satirical skill emerged from the vibrant tapestry of literary history and took the stage where the brilliant Shakespeare once performed. Ben Jonson, a towering playwright of his era, carved his name into the annals of dramatic ingenuity through a unique blend of sharp intellect, biting humor, and audacious creativity.

In one of the most hallowed corners of London’s intellectual discourse, the Mermaid Tavern, Jonson engaged in legendary “wit-combats” with none other than the bard (Shakespeare’s nickname) himself.

In these verbal jousts, a symphony of words and ideas collided, leaving an indelible mark on the very fabric of artistic camaraderie. It was a testament to the rich tapestry of literary camaraderie that weaves the legacy of creative minds.

Jonson’s pen dripped with the ink of satire, crafting masterpieces that held a mirror to the follies and foibles of his society. In “Every Man in His Humour,” he unfurled a tableau of human idiosyncrasies, while “Bartholomew Fair” became a caustic exploration of the chaos and carnival of life. “Volpone,” a jewel in his theatrical crown, wove a tapestry of deception and greed, painting a vivid portrait of human nature’s darker shades.

The royal court of King James I beckoned, its opulent corridors a stage where Jonson’s genius could shine. Amidst the grandeur, extravagant musical entertainments unfurled, a symphony of artistry that mirrored the majestic tapestry of the court itself. It was a realm where Jonson’s talents found a harmonious resonance, echoing through the corridors of power.

Yet, even amidst the brilliance of his creative mind, shadows cast their pall. In 1598, Jonson’s reputation for violent outbursts took a tragic turn when a heated argument escalated into a fatal encounter. The life of an actor and his friend was cut short in a heart-wrenching tragedy born from a moment of fiery confrontation. In the crucible of that tragic altercation, Jonson’s life would forever be marked by the irrevocable stain of regret.

The scales of justice tilted, and Jonson narrowly escaped the executioner’s embrace. But the scars of his actions remained, etched into his flesh as a branded reminder of the price of anger and impulsiveness. Behind the bars of a prison cell, he confronted the weight of his deeds and the darkness of his own humanity.

In the mosaic of history, Ben Jonson emerges as a paradoxical figure: a playwright of unparalleled genius and a man touched by the tempestuous currents of his own emotions. His words ignited laughter and contemplation, and his wit carved pathways through the human psyche.

And yet, his journey was marked by both the soaring heights of artistic brilliance and the depths of personal tragedy. In his legacy, the echoes of “wit-combats” at the Mermaid Tavern and the resounding notes of his satirical symphonies endure, a testament to the complexities of the human spirit and the indomitable power of creativity.

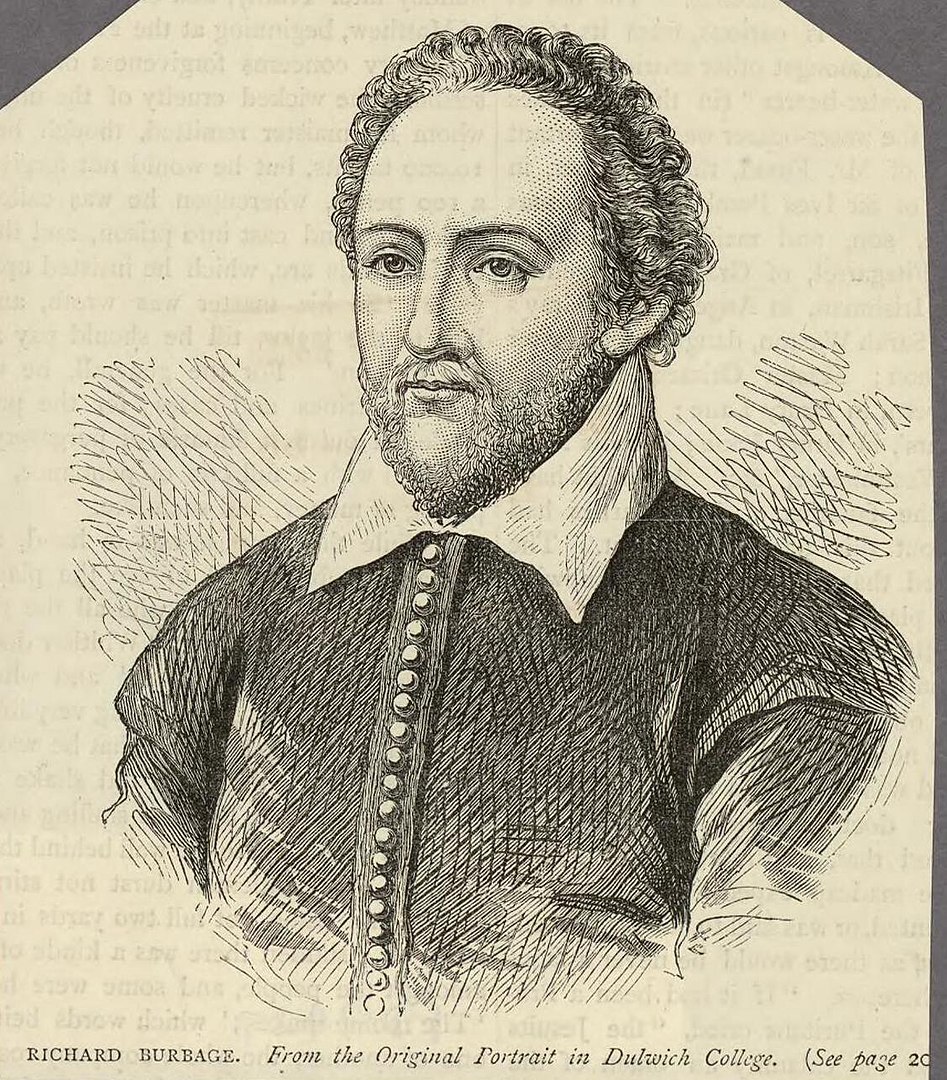

Richard Burbage and William Kemp: Stars of the Elizabethan Era

In the annals of theatrical history, a profound transformation unfolded during the Elizabethan era as actors cast off the cloak of vagabondage to rise as respected artisans upon the stage. This metamorphosis was a symphony conducted by the harmonious chords of patronage and regal encouragement, elevating the status of actors from wandering minstrels to esteemed artists.

Nobles of distinction, such as the illustrious Earls of Leicester and Southampton, unfurled their patronage like a rich tapestry, adorning the realm of thespian artistry with threads of honor and prestige.

A regal presence graced the stage itself as Queen Elizabeth I extended her personal encouragement, casting a radiant light upon the path of thespian endeavor. It was a time when the shadows of uncertainty were replaced with the splendor of recognition, and the actors emerged from the wings to take their rightful place in the spotlight.

Among these luminaries, two stars blazed with unparalleled brilliance: Richard Burbage and Will Kemp (William Kempe). Their artistry became the touchstone of a new era, leaving an indelible mark on the canvas of dramatic history.

Richard Burbage, a tragedian of unparalleled depth, stood as a colossus upon the stage. The very foundations of the Globe Theatre, an iconic emblem of Elizabethan artistry, were laid by his brother Cuthbert. As the curtain rose, Burbage breathed life into a pantheon of Shakespearean characters, each a masterpiece of emotion and complexity.

From the hunchbacked malevolence of Richard III to the star-crossed passion of Romeo, from the martial valor of Henry V to the tormented introspection of Hamlet, Burbage wove a tapestry of humanity onto the stage. Othello’s searing jealousy and King Lear’s heart-rending descent all found their embodiment in Burbage’s performances, each a symphony of emotion that resonated within the hearts of the audience.

Beside him, the irrepressible spirit of William Kemp danced like a playful gust of wind. As a comedian, Kemp wielded laughter like a magician’s wand, captivating audiences with his antics and jests. His feet seemed to have a mind of their own, tracing lively patterns on the stage as he portrayed characters with boundless exuberance.

In a world where tragedy and comedy coexisted, Kemp painted smiles upon the faces of those who watched, his performances a reminder that even in the depths of human drama, the light of mirth could never truly be extinguished.

And so, within the hallowed halls of the Elizabethan theater, a transformation took root. Actors emerged from the shadows of societal disdain, ascending the stage to claim their rightful place as artisans of expression.

The patronage of nobles and the benevolent gaze of a queen turned the tide, raising the status of actors to new heights. Among them, Richard Burbage and William Kemp stood as luminous beacons, their performances breathing life into the immortal verses of Shakespeare and kindling a fire of respectability that would burn for generations to come.

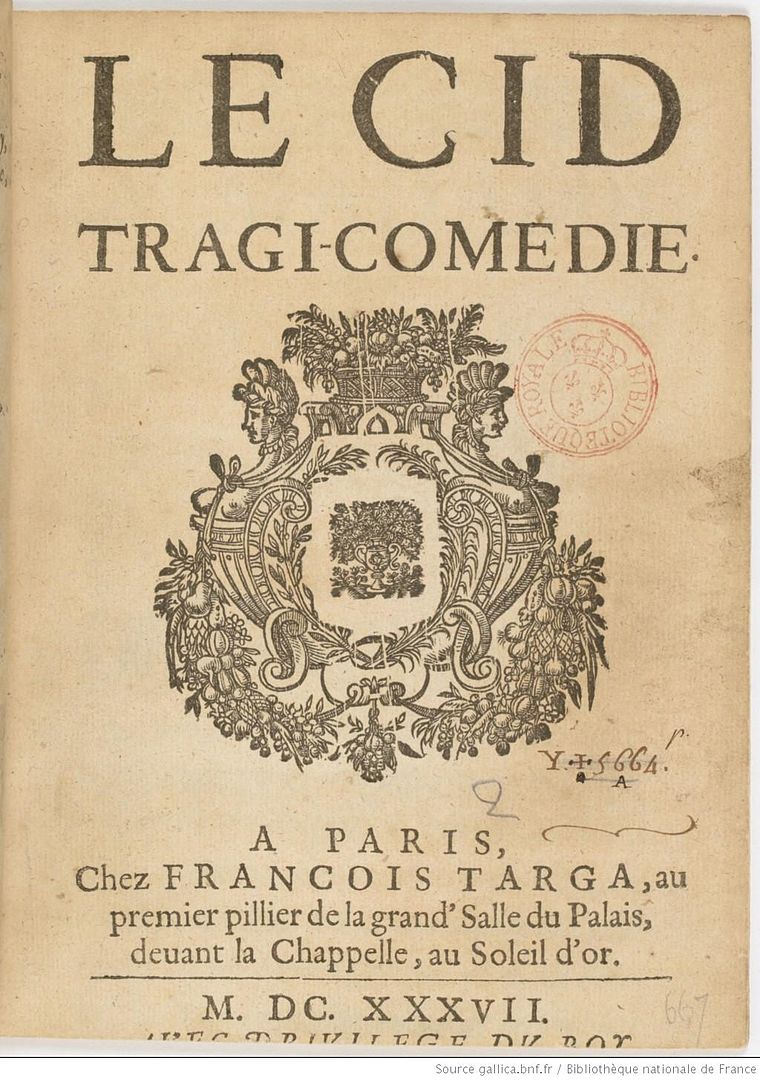

Le Cid: The Beginning of French Drama

In the realm of French theater, the pages of history bear witness to a dramatic evolution that unfolded with the majestic sweep of time. Until the 17th century, the stage resonated with the echoes of Italian playwrights’ classical works, their verses painting vibrant tapestries of human emotion.

Yet it was the visionary cardinal, Richelieu, a maestro of intrigue and governance, who would cast a transformative spell upon the theatrical landscape of France.

Under his watchful gaze, the curtains of a new era were drawn aside, and a resplendent theater emerged in the heart of Paris. It was a testament to Richelieu’s determination to foster the blossoming of native creative expression.

The year 1637 heralded a momentous turning point as Pierre Corneille, a luminary of poetic artistry, unveiled his magnum opus, “Le Cid.” Through the tale of the Spanish hero El Cid, the very essence of French drama began to unfold, weaving a tapestry of passion and destiny that would captivate hearts for generations to come.

But Corneille was merely the herald of a theatrical renaissance, a harbinger of the grandeur yet to come. In the 1660s, a name echoed through the corridors of time, a name synonymous with classical tragedies that would ignite the imagination of countless souls: Jean Racine.

With poetic brushstrokes, Racine crafted masterpieces like “Andromaque, Iphigenie, Britannicus” and the hauntingly poignant “Phèdre.” His quill became an instrument of divine reckoning, and his verses became a mirror to reflect the passions that both bind and emancipate humanity.

In 1677, as his fame soared to its zenith, Racine chose to withdraw from the proscenium’s embrace, forsaking the realm of playwriting to inscribe the annals of history with the chronicle of King Louis XIV’s reign. It was a testament to the multifaceted genius that flowed through his veins, a testament to the profound interplay between theater and the grand tapestry of the world.

Playwrights of Spain’s Golden Age

In the shadows of Seville’s prison walls, a tale was born that would blaze across the pages of literary history like a star streaking through the night sky. Miguel de Cervantes, a man of both misfortune and brilliance, found solace amidst his debts by weaving the fabric of an extraordinary narrative.

It was in the year 1597 that the first brushstrokes of “Don Quixote” were painted, a masterpiece that would forever etch his name into the annals of literary greatness.

Through the hallowed pages of “Don Quixote,” Cervantes conjured a world where madness and valor intermingled, where a gallant knight pursued windmills with the fervor of a crusader, and where the very essence of human nature was distilled into an epic odyssey.

The resonance of this novel reached far beyond the confines of ink and parchment, finding its way into the very heartbeats of a nation. So profound was its impact that even King Philip III himself found his curiosity piqued by a man ensnared in laughter while reading the tale, remarking that he must be either “mad or reading Don Quixote.”

Yet, Cervantes’ artistry extended beyond the realm of prose, for he was a maestro of the stage as well. Over thirty plays flowed from his pen, each a testament to his creative prowess. However, in the early 1600s, it was Lope de Vega who stood as the colossus of Spanish theater, his words igniting the stage with a fervor that could not be contained.

Amidst the rustic drama of “Fuenteovejuna,” penned in 1614, Lope masterfully depicted a social uprising, a rebellion that echoed through the ages as Europe’s first portrayal of its kind.

Cervantes, Lope, and the devout playwright Pedro Calderón danced upon the tapestry of Spanish theater, their collective brilliance igniting the Golden Age.

Together, they kindled the flames of human emotion, their words breathing life into characters and tales that would resonate across borders and generations. The stage became their canvas, a realm where human nature was explored in all its facets, and the heart of Spain found its voice in the eloquence of their verses.

And so, within the quill strokes and spoken words of these literary titans, the Golden Age of Spanish theater was ushered into existence.

It was a time when ink and imagination melded seamlessly, when the echoes of laughter and applause reverberated through the air, and when the power of storytelling shaped the destiny of a nation and illuminated the pathways of the human soul.

Louis XIV’s Theater Revolution

In the year 1680, a momentous chapter unfolded in the realm of theater as King Louis XIV of France orchestrated the establishment of the world’s inaugural national theater.

This audacious endeavor was undertaken with a grand ambition: to extend the embrace of theater across the expanse of his entire kingdom. To materialize this vision, King Louis XIV orchestrated the amalgamation of three theatrical companies situated in Paris.

Among these, one was under the stewardship of the acclaimed actor and playwright Molière. This amalgamation culminated in the birth of the new theater, christened the Comédie-Française, a distinction that set it apart from its counterpart, the Comédie-Italienne.

The allure of the Comédie-Française beckoned theater enthusiasts far and wide, enticing them with a rich tapestry of comedies that elicited laughter and commanding dramas that stirred emotions.

Following a year-long trial phase, a pivotal shift occurred: actors were accorded stable and guaranteed remuneration. Subsequently, the trajectory led to the offering of permanent positions and the assurance of a dignified retirement for these thespians.

This evolutionary stride marked one of the most momentous advancements in the annals of modern theater in Europe.

King Louis XIV’s vision materialized into an institution that bridged both artistic and societal spheres, shaping the trajectory of theater not solely within France but echoing across the world and imprinting its indelible mark on the theatrical tapestry of history.

Commedia dell’arte

In the bustling squares and narrow streets of Renaissance Europe, a vibrant and dynamic form of theater emerged, captivating audiences with its spontaneity, humor, and vivid characters. This was the realm of Commedia dell’arte, a theatrical tradition that danced to the rhythms of Italian folklore and ancient carnival revelry.

During the span of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, Commedia dell’arte flourished as a lively and improvisational art form. At its heart were skilled and talented actors, virtuosos of their craft, who brought to life an array of characters in a realm where creativity knew no bounds.

Unlike the structured scripts of traditional theater, Commedia dell’arte was a celebration of actors’ ingenuity—a symphony of wits and talents that unfolded within a fundamental framework.

These actors, known as “arte” or “artisans,” embraced their roles with fervor, weaving intricate tales of love, intrigue, and misadventure. The canvas on which they painted was a basic outline, a blueprint that allowed the spontaneous creation of actions, dialogues, and interactions.

It was a theatrical dance of unscripted brilliance, where actors breathed life into characters and narratives flowing from their imaginations.

To enrapture audiences with an ever-evolving tapestry of entertainment, Commedia dell’arte performers adorned their acts with a dazzling array of artistic elements. Mime and movement, dance and song, acrobatics and jests—all found a home within this vibrant realm.

The actors donned masks to portray characters, each mask serving as a window into distinct personalities, a world of quirks and idiosyncrasies adding a unique flavor to the unfolding drama.

With every gesture, every step, and every word, the players conjured iconic figures that transcended time and language. The nimble and mischievous Harlequin, characterized by his colorful costume, embodied a playful spirit.

On the other hand, Pantaloon gave the impression of being a lovelorn and despondent figure due to his pursuit of affection and endless romantic misadventures.

Additionally, the brash and boastful Scaramuccia (English: Scaramouch), a swaggering captain whose arrogance was matched only by his comedic mishaps, completed the ensemble of characters.

Dialects danced in the air, giving rise to delightful misunderstandings and uproarious exchanges that left audiences in fits of laughter. The world of Commedia dell’arte was a spectacle for the senses, a mosaic of talents and emotions that painted a portrait of life’s complexities, joys, and foibles.

In the tapestry of European theater, Commedia dell’arte stands as a vibrant and enduring masterpiece, a testament to the power of human creativity and collaboration.

Its legacy continues to echo through the ages, a testament to the enduring allure of theater, which celebrates the boundless ingenuity of the human spirit.