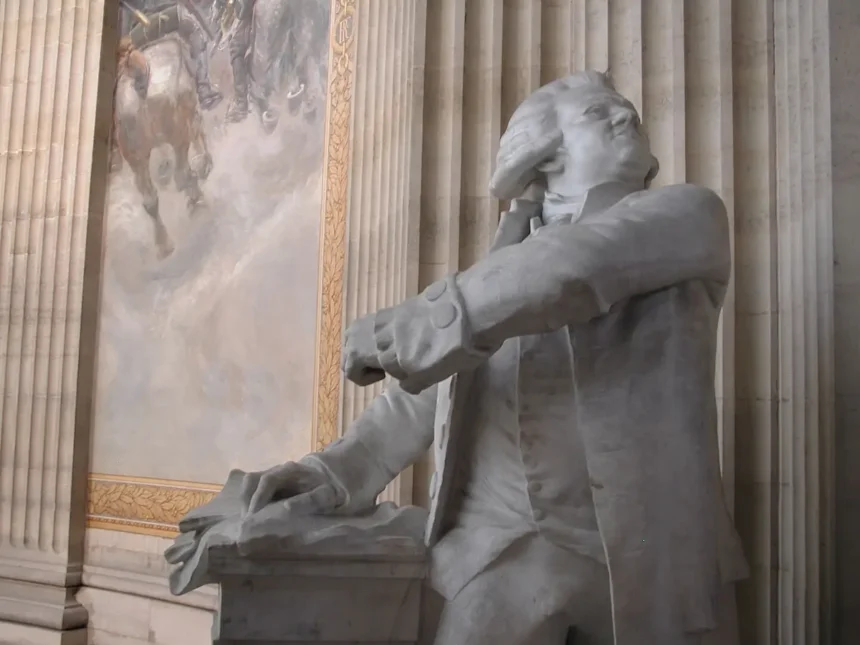

Honoré-Gabriel Riquetti, Count of Mirabeau, was a writer and a political figure at the start of the French Revolution. After a tumultuous youth marked by romantic escapades, he was elected, despite being a noble, as a deputy for the Third Estate in 1789. He quickly made his mark with his eloquence and sought to establish the principle of a constitutional monarchy based on the English model, with power shared between the king and the Assembly. Although distrusted by many deputies, he became president of the Constituent Assembly but was largely ignored by King Louis XVI, who paid handsomely for his advice.

Mirabeau’s Tumultuous Youth

Born in the Gâtinais at the Château de Bignon, the future Count of Mirabeau was the fifth child and second son of Victor Riqueti, Marquis de Mirabeau, and Marie Geneviève de Vassan. Heir to the family name after the death of his elder brother, he was born with a clubfoot and two molar teeth. At the age of three, he contracted confluent smallpox, which left deep scars on his face due to the careless application of an eye ointment, further adding to his natural unattractiveness.

He was a turbulent, undisciplined child but highly intelligent with a prodigious memory. His father recognized his abilities but claimed he had an inclination toward evil. In 1767, he enlisted him in the army but refused to purchase him a commission.

In July 1768, Mirabeau secretly left his garrison and took refuge in Paris.

This escape led to his first imprisonment at the citadel on the Île de Ré. He was released when he requested to join the Corsican expedition, where he distinguished himself. Upon his return, he reconciled with his father (October 1770), and in 1771, he was received at court.

A new dispute arose between him and his father, who wanted to force him to work. At that time, he married a wealthy heiress, Émilie de Marignane (1772), but did not receive any dowry. Harassed by creditors, he was imprisoned in the Château d’If. In May 1775, Honoré was transferred to the Fort de Joux, where the less strict surveillance allowed him to visit the town.

There, he met the Marquis de Monnier, who was married to Marie-Thérèse Richard de Ruffey, the daughter of a president of the Chamber of Accounts of Burgundy. This was the beginning of Mirabeau’s affair with the woman he immortalized as Sophie. Mirabeau fled to Switzerland, then to Holland with Madame de Monnier, who managed to join him. Their respite was brief. They were arrested in Amsterdam in May 1776. Transferred back to France, Mirabeau was imprisoned at the Château de Vincennes in June 1777, where he wrote two famous works: Letters to Sophie and Letters de Cachet.

Mirabeau was released in 1780 after three and a half years in detention. His wife Émilie obtained a legal separation, and in 1786, Mirabeau returned to Berlin on a secret mission.

Mirabeau: Revolutionary Leader

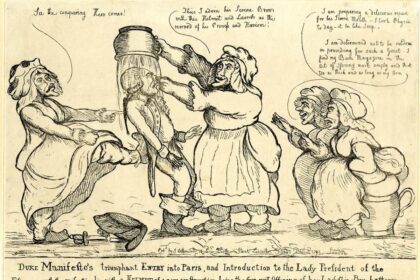

Upon the announcement of the convocation of the Estates-General, Mirabeau launched a fierce campaign in Provence against the aristocracy’s privileges and, despite being a noble, was triumphantly elected as the representative of the Third Estate for the Seneschal of Aix. Linked to the Duke of Orléans, he asserted himself at the Estates-General with his exceptional oratory skills, making people forget his “grand and striking ugliness.

“

On June 17, 1789, the deputies of the Third Estate declared themselves the National Assembly, gathered in the Tennis Court, and vowed to draft a constitution for the country. On June 23, 1789, he allegedly delivered the famous statement: “We are here by the will of the people, and we shall only leave by force of bayonets,” refusing the king’s order to dissolve the new assembly. He then succeeded in having the principle of inviolability of deputies adopted.

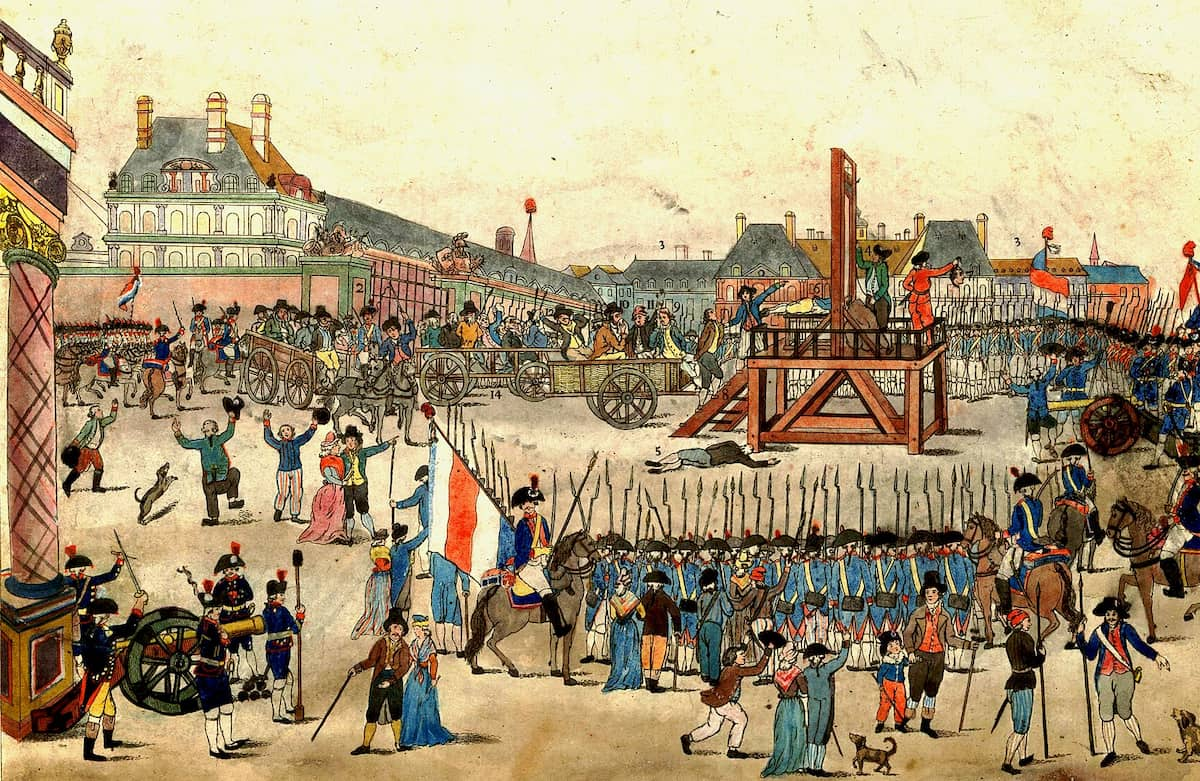

Becoming a popular idol, he fueled unrest with an army of publicists and played a major role in drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Mirabeau also passed a new tax, the patriotic contribution of a quarter of incomes, and arranged for the nationalization of church property. At this point, Mirabeau appeared to be the man capable of achieving a reconciliation between the king, the aristocracy, and the Revolution, as desired by La Fayette. But while his eloquence captivated the Assembly, his private life scandalized it, and his political ambitions alarmed it.

Mirabeau’s Duplicity and Death

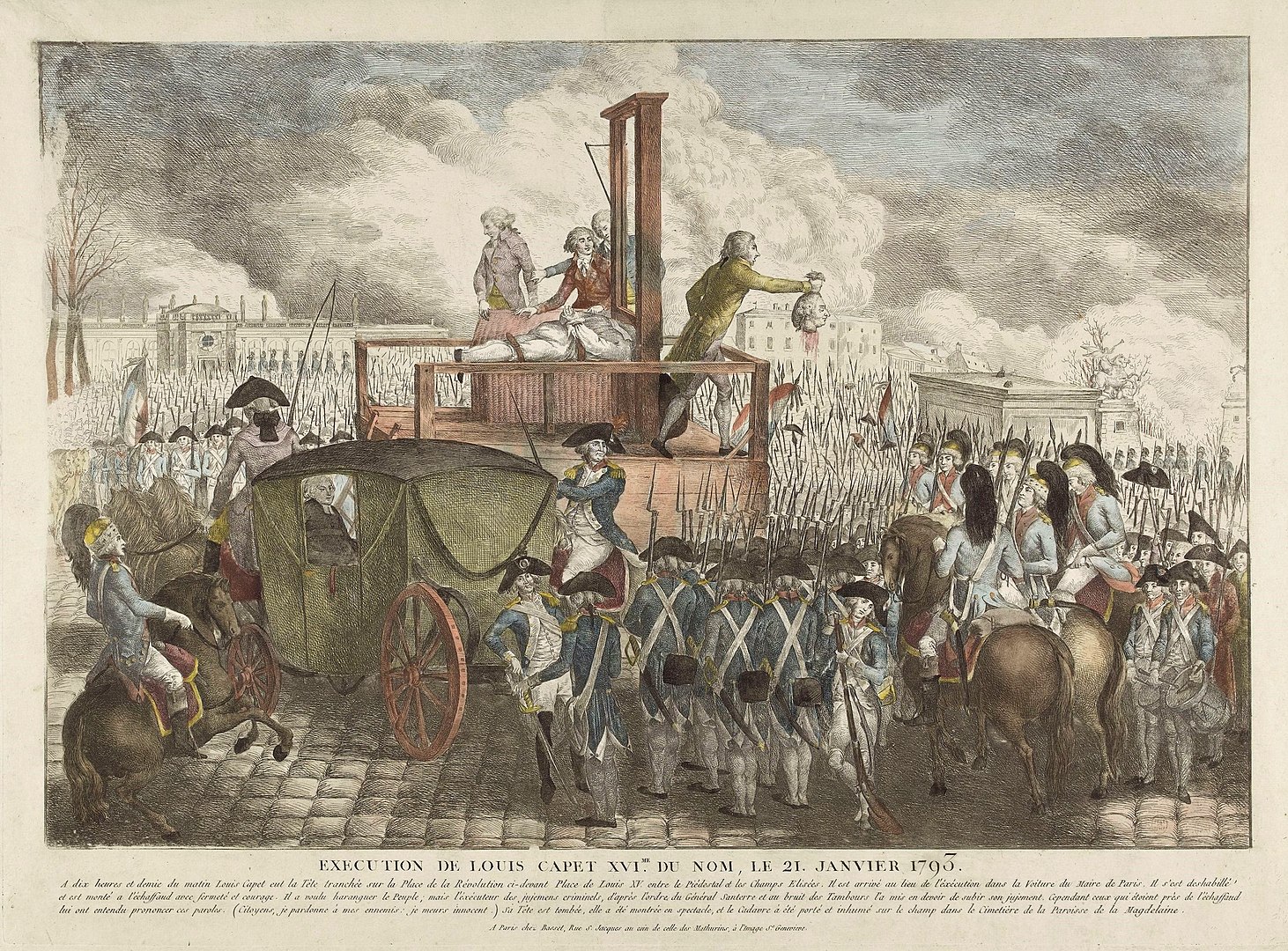

Troubled by the excesses of the Revolution, Mirabeau drew closer to the court and Louis XVI. His first memorandum to the king, dated May 10, 1790, concluded with the words: “I promise the king loyalty, zeal, energy, and courage of which people may have no conception.” Now an advocate of constitutional monarchy, Mirabeau sought to reconcile this idea with revolutionary principles. He defended the king’s right to an absolute veto against the majority of the National Constituent Assembly, which voted for a suspensive veto. Mirabeau hoped to become a minister mediating between the National Assembly and the king. However, in November 1789, the Assembly dashed his ambitions by declaring that no member of the Constituent Assembly could become a minister.

Through the Count of La Marck, Mirabeau sent notes to Louis XVI on organizing the counter-revolution and, with La Fayette—whom he disliked—tried to secure the king’s right to control war and peace in the new constitution. His proposals to maintain the throne and end the Revolution were never fully heeded by the king, who trusted him no more than La Fayette, commander of the National Guard.

His duplicity did not go unnoticed by some revolutionaries, who denounced his corruption.

Despite these complications and some animosities within the Assembly, Mirabeau regained his popularity, became a member of the Paris departmental directorate, and was elected president of the Constituent Assembly on January 30, 1791. Exhausted by a life of excess and work, he died suddenly on April 2, 1791. His body was laid to rest in the Panthéon but was later removed after the discovery of the iron chest, which contained his correspondence with the king. With his death, the Revolution lost one of its key figures and its most powerful orator. His Oratory Works and the Correspondence between the Count of Mirabeau and the Count of La Marck were published posthumously.