Fifty-two regular Sundays, a week each for celebrating the main Christian holidays—Easter, Christmas, and Pentecost—along with other obligatory holidays like Epiphany, Baptism, Candlemas, Palm Sunday, Ascension, Trinity, the Feast of Corpus Christi, the Sacred Heart, Transfiguration, Exaltation of the Cross, Feast of the Holy Family, Immaculate Conception, Saint Joseph’s Day, Feast of Saints Peter and Paul, Assumption of the Virgin Mary, and All Saints’ Day, plus days dedicated to various saints—patrons of cities, guilds, and so on—along with days for their commemoration and associated events, as well as entries of rulers, bishops, and other important figures. Altogether, about a third of the year was spent by medieval city dwellers in leisure.

- Go to Church and Listen to a Preacher

- Watch a Performance

- Enjoy Wandering Performers

- Listen to Music or Poetry

- To Dance

- To Visit a Fair

- To Participate in a Carnival

- Greeting a Guest or Ruler

- Watching a Knightly Tournament

- Participating in Sporting Competitions

- To Play

- To Go to the Bathhouse and Have a Good Drink

- To Rest by the City Fountain

- To Watch an Execution

Go to Church and Listen to a Preacher

Festive church services were performed with great pomp, featuring the best choir singers. From the 9th–10th centuries, festive Mass began to resemble an allegorical play due to performances based on Old Testament, Gospel, or hagiographic stories. These performances lasted until about the 13th century when they were replaced by city theatrical events.

On holidays, women tried to dress up: they went not only to the service but also “to see people” — to look at others and show themselves. Everyone in the church had their place, determined by their social status. On Sundays and holidays, working was forbidden, and after Mass, parishioners often sought entertainment: dancing and singing often occurred right in the churchyard, although clergy at least formally condemned such behavior.

Sometimes, a preacher would visit the city, and if he did not perform in the church courtyard, the townspeople would build him a platform where he could pray with the congregation and then deliver a scathing sermon.

Watch a Performance

Medieval theatrical performances primarily provided spiritual entertainment for the townspeople and explained the Holy Scriptures in the vernacular in various forms. The basis of a miracle play was apocryphal Gospels, hagiographies, and chivalric romances. In England, miracle plays were usually staged by members of craft guilds in honor of their patrons. In France, they were popular among members of puy—urban associations for joint pious activities, music, and poetry competitions.

The plot of a mystery play was usually the Passion of Christ, the expectation of the Savior, or the lives of saints. Originally, mysteries were part of church services, but they later moved to the churchyard or cemetery, and then to city squares. They were performed not by professional actors, but by clergy and members of the puy.

Moralities were something between religious and comic theater. In allegorical form, they showed the struggle between good and evil in the world and in the individual. The outcome of this struggle was either the salvation or damnation of the soul.

Performances were announced in advance; posters were hung on city gates, and during the performance, the city was carefully guarded “so that no unknown people could enter the said city on that day,” as stated in a 1390 document preserved in the city hall archive in Tours.

Despite the conventionality of the productions, what happened on stage was entirely fused with reality for the audience, and tragic events were mixed with comic scenes. Spectators often became participants in the action.

Enjoy Wandering Performers

One could also enjoy entertainment without moral lessons, like watching wandering performers. Around the 14th century in France, troupes of professional actors began to form—such as the “Brotherhood of the Passion” and the “Carefree Lads.” Traveling performers—histriones, spielmänner, and jugglers—used all sorts of tricks to amaze and amuse the public. The “Teaching of Troubadour Giro de Calancon to a Juggler” (he lived in the early 13th century) lists a whole range of skills an actor needed:

[He] should play different instruments; juggle balls on two knives, tossing them from one blade to another; show puppets; jump through four hoops; don a fake red beard and costume to dress up and scare fools; train a dog to stand on its hind legs; master the art of a monkey handler; amuse the audience with comical depictions of human weaknesses; run and leap on a rope stretched from one tower to another, making sure it doesn’t give way…

Listen to Music or Poetry

Instrumental music was mainly the domain of jugglers and minstrels, who sang, danced, and performed to the sound of their instruments. Besides various wind instruments (trumpets, horns, flutes, Pan flutes, bagpipes), harps and types of bowed instruments—the ancestors of the future violin, like the crwth, rebab, and vielle or fiddle—were introduced into musical life over time.

Moving from place to place, jugglers performed at festivals in courts, castles, and city squares. Despite church persecution, jugglers and minstrels managed to gain the opportunity to participate in religious performances in the 12th–13th centuries.

In the south of France, lyrical poets were called troubadours, in the north trouvères, and in Germany Minnesingers. The lyric of the Minnesingers belonged to the nobility, heavily influenced by knightly poetry and the love songs of the troubadours. Later, the art of versification in German cities was taken up by the Meistersingers, for whom poetry became a special science.

Like craftsmen, city poets formed societies similar to guilds. In Ypres, Antwerp, Brussels, Ghent, and Bruges, guilds of so-called “rhetoricians”—craftsmen and merchants who took charge of poetry—held festivals. Each guild had its own coat of arms and motto in the form of a charade, as well as a special hierarchical structure: dean, standard-bearer, jester, and other members of the “elder council.” The city authorities funded competitions in poetry and acting, awarding several prizes: for literary achievements, the best jester’s line, the richest costume, and the most magnificent entry into the city.

To Dance

Dance was a favorite pastime for all social classes in medieval society; no celebration was complete without dancing. Jugglers made the dance more complex by adding acrobatic elements, but townspeople loved to move themselves, not just watch the professionals. The church usually opposed such entertainments, and city governments did not always have a favorable attitude towards dancing. However, later on, authorities began to permit dances in city halls, and by the end of the 14th century, so-called dance houses began to appear. A dance house was usually located near or opposite the town hall and church. The loud music and laughter disturbed the pious atmosphere of the parishioners and church staff, causing their displeasure and endless complaints.

In Nördlingen, Bavaria, the dance house was located in a three-story building. During fairs, the ground floor was connected by passages to nearby butcher shops and a tavern, allowing visitors to move between establishments. In buildings with multiple floors, the upper-level halls were typically reserved for burghers of noble origin, while the lower levels were at the disposal of ordinary townspeople. In some cities, the dance house also served as an inn, and in Munich and Regensburg, prisoners were even held in the basement of the “Tanzhaus” (dance house).

Moreover, there were dance houses designed exclusively for commoners: a wooden platform slightly raised above the ground was covered with a roof supported by four columns. Musicians would be positioned on this platform, and men and women would dance in a circle around them. While the nobility preferred measured and ceremonial processional dances and guild festivals featured dances with hoops, swords, and other objects symbolizing artisanal products, the townspeople favored improvisational dances and round dances, which the church considered crude and shameless.

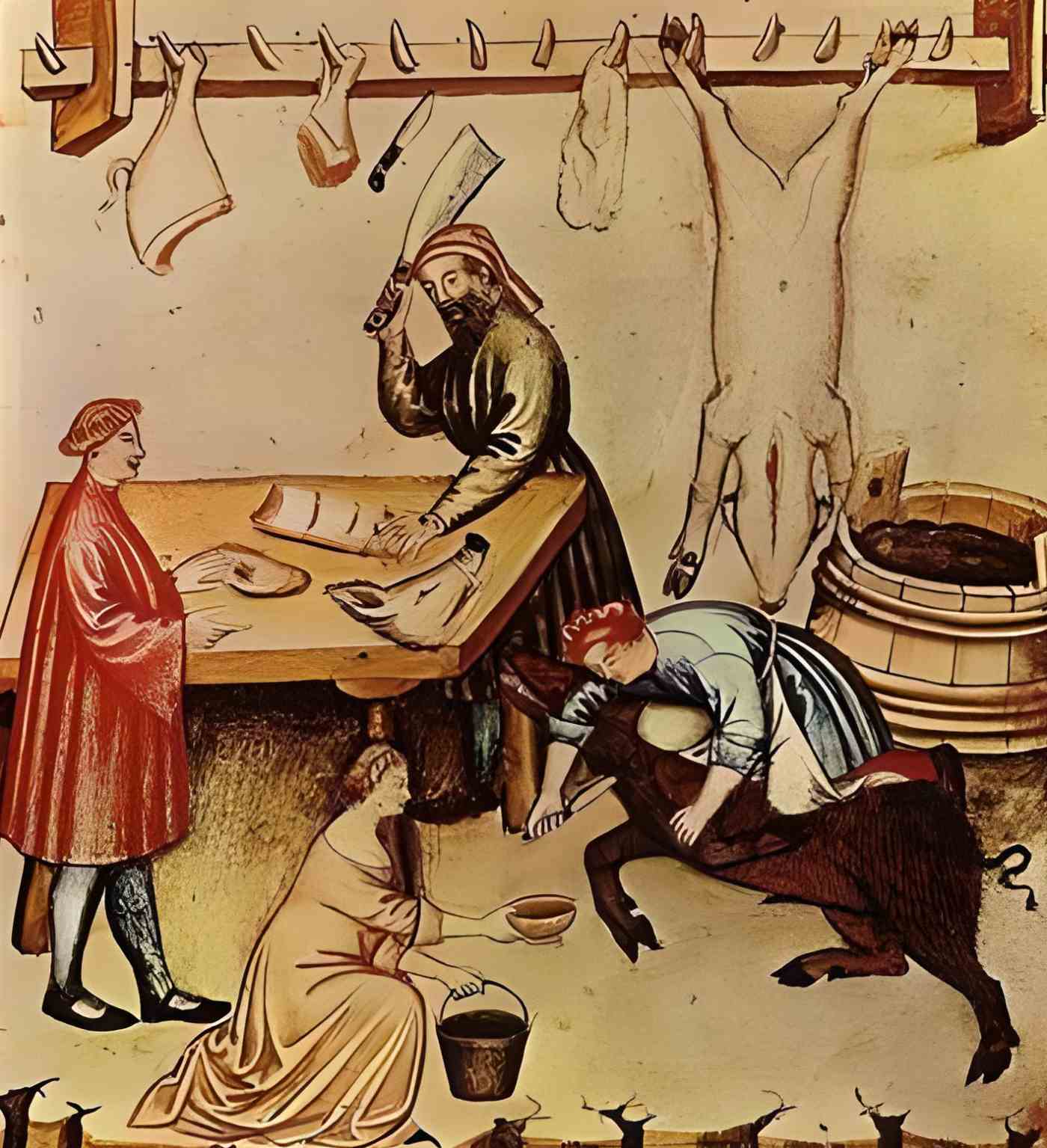

To Visit a Fair

Weekly markets served the townspeople regularly, but fairs were held much less frequently—only once or a few times a year: at Christmas, Easter, or on the feast day of a local saint, the city’s patron or the patrons of trade and craft guilds.

For example, the fair in Saint-Denis, outside the walls of Paris, was held once a year but lasted an entire month. During this time, all trading in Paris ceased and moved to Saint-Denis. Residents flocked there not only to shop but also to marvel at exotic items from distant lands, to watch performances by jugglers, acrobats, and trained bears, and to listen to stories told by merchants who had traveled overseas. The spectacle was so popular that Charlemagne issued a special order to his officials to “ensure that our people perform the work they are required to do by law, rather than waste time wandering through markets and fairs.”

Fairs attracted all sorts of riff-raff, often leading to fights and disturbances. This is why, for a long time, fairs were only allowed in cities where there was a bishop or ruler who could maintain order and resolve disputes between participants. In medieval England, there were even special courts with simplified procedures to ensure quick resolution of cases. These were called “courts of piepowder”—so named in 1471 by the English Parliament, which decreed that all persons associated with fairs were entitled to demand this type of court.

To Participate in a Carnival

Carnival was inseparable from Lent: it was the last multi-day celebration before a long period of abstinence, and it was accompanied by feasts, masquerades, processions, and mock fights with cheeses and sausages. Carnival was a realm of gluttony, chaos, and celebration of all things corporeal. Masks and disguises, half-animal half-human figures, kings of fools, ships of fools, and the election of an “ass pope”—all church and secular rituals were translated into the language of buffoonery, and symbols of authority were publicly mocked. Entire church services and sacred texts were turned upside down. The main events of the carnival took place in churches, although these obscenities had been officially banned with interdicts since the 13th century.

In a message sent by the theological faculty in Paris to the bishops of France in 1445, the carnival was described vividly:

One can see priests and clerics wearing masks and monstrous faces during services. They dance in the choir, dressed as women, pimps, and minstrels.

buy super kamagra online https://infobuyblo.com/buy-super-kamagra.html no prescription pharmacy

They sing indecent songs. They eat sausages in the corners of the altar while the priest celebrates Mass. There, too, they play dice. They burn foul-smelling smoke from the soles of old shoes. They jump, run around the church without shame. Then they ride through the city in dirty carts and carriages, making obscene gestures and uttering shameful and filthy words to the laughter of their companions.

During the carnival, anything forbidden on ordinary days was allowed, hierarchies were broken, and established norms were turned upside down—but as soon as the festival ended, life returned to its usual course.

Greeting a Guest or Ruler

Ceremonial entries of emperors, kings, princes, legates, and other lords into their subordinate cities were always laden with a multi-layered symbolic meaning: they reminded people of the nature of power, celebrated victories, and affirmed political dominion over distant territories. These events occurred quite often: in the Middle Ages and even in the Early Modern period, royal courts were itinerant — to maintain power, kings had to constantly move from place to place.

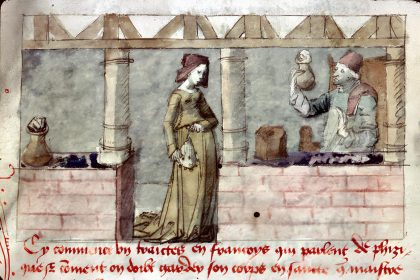

The ceremony consisted of several acts, each strictly regulated. It all began with the greeting of the ruler, often far outside the city; this was followed by the reception of the crowned figure at the city walls, the handing over of the keys, the opening of the city gates, and delegations from the nobility and clergy. From the gates, the procession moved along the main streets of the city, which were strewn with fresh flowers and green branches.

Finally, in the central city square, oxen and game were roasted, and barrels of wine were rolled out for all the townspeople. In 1490, during the entry of Charles VIII into Vienne, a “Fountain of Good and Evil” was installed, which spouted red wine from one side and white wine from the other. Such feasts were intended to embody the image of a fairytale land of abundance, a vision the ruler was expected to present to his subjects at least once.

For the guest, elaborate performances were staged. In 1453, a whole play was performed in Reggio: the city’s patron saint, Saint Prospero, hovered in the air with a host of angels who asked him for the keys to the city to hand them over to the duke, while hymns were sung in his honor. When the procession reached the main square, Saint Peter descended from the church and placed a wreath on the duke’s head.

In the German lands, the sovereign often entered the city surrounded by criminals sentenced to exile, and they didn’t just accompany him in the procession but held onto the edge of his garment, the harness, saddle, or stirrup of his horse — thus allowing them to return to the city. For example, in 1442, King Frederick III ordered eleven people to accompany him to Zurich, and in 1473, thirty-seven to Basel. However, city authorities could expel the criminals again as soon as the ruler left the city.

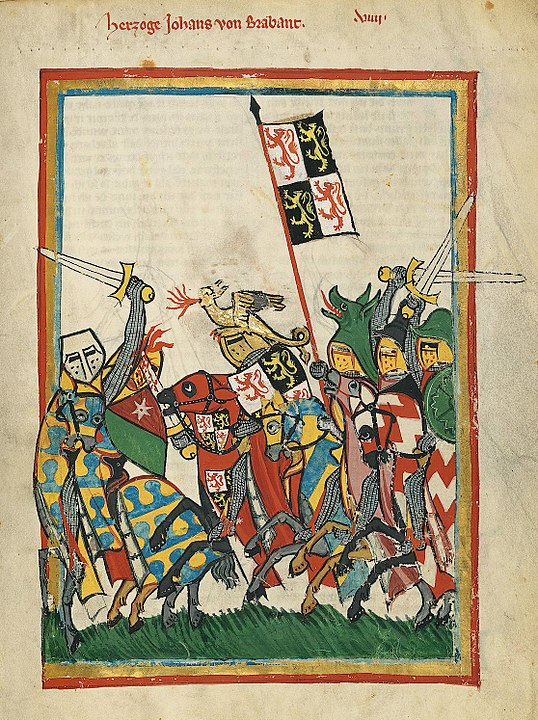

Watching a Knightly Tournament

The tournament was a true celebration of martial valor and chivalric honor. Everyone wanted, if not to participate, then at least to watch how the noble youth earned glory and spoils. Initially, the event resembled a mix of a fair and a real battle: participants would clash wall to wall, some receiving serious injuries or even dying, and a diverse crowd gathered around, consisting of not only knights, their squires, foot soldiers, and servants, but also blacksmiths, merchants, money-changers, and onlookers.

Under the influence of chivalric romances, tournaments gradually became more organized, with participants using specialized weapons. Knights would face off in one-on-one duels, and the lists would be fenced off. Stands were built for spectators, each with its own “queen,” and the prize for the best tournament fighter was traditionally awarded by women. In 1364, Francesco Petrarch described the atmosphere of a Venetian joust (from the Italian word giostre — “duel”) as follows:

“Below, there is not a free spot… the vast square, the very temple [of Saint Mark], the towers, the roofs, the porticoes, the windows are not only full but overfilled and crammed: an incredible multitude of people hides the face of the earth, and the joyful, numerous population of the city, spreading around the streets, only increases the merriment.”

Eventually, tournaments turned into a costly and sophisticated courtly entertainment, accompanying various celebrations such as the wedding of a ruler, coronation, or the conclusion of peace or an alliance — along with festive masses, processions, banquets, and balls, most of which were not intended for ordinary townspeople.

The townsfolk responded with a parody “knightly tournament” (often organized during the big carnival at Maslenitsa), where the entire chivalric ritual was turned upside down. A person imitating a knight would ride out for a duel with a basket for a helmet on their head, sitting on an old nag or a barrel, and threaten the opponent with a rake or something from the kitchen instead of a lance. After the event ended, everyone would immediately set off to celebrate with a merry feast.

Participating in Sporting Competitions

The burghers had every opportunity to train and compete in the use of real weapons. For practice, archery societies and fencing schools were organized in Flemish, northern Italian, English, French, and German cities, as well as in Krakow, Kyiv, and Novgorod. Associations of archers and fencers had their own charters and resembled guilds.

Training was conducted in various disciplines, but each city chose a specific type of combat for its competitions. For example, in Spanish cities, preference was given to duels with cold steel and mounted bullfights, in southern England and Novgorod — fistfights, and in German and Flemish cities — fencing and wrestling.

In Italy, the games and competitions of city-republic residents resembled drills. In Pavia, for instance, the townspeople were divided into two groups, given wooden weapons, and wore protective helmets. Prizes were awarded to the winners. In river cities, battles could be staged for the symbolic capture of a bridge. Images of a bustling crowd fighting on such a bridge were a favorite subject of engravings from that era: in the foreground, gondoliers are rescuing those who have fallen into the water, while numerous spectators crowd the windows and roofs of nearby houses.

In England, playing ball was a popular pastime for young men.

Everyone who wished could participate, and there were almost no rules. The ball, stuffed with bran or straw, could be kicked, dribbled with feet, rolled, or carried in hands. The goal of the game was to get the ball across a certain line. In cities, such large-scale skirmishes were fraught with great dangers, and it was no coincidence that in London, Nuremberg, Paris, and other places, restrictions were introduced early on to temper the players’ fervor.

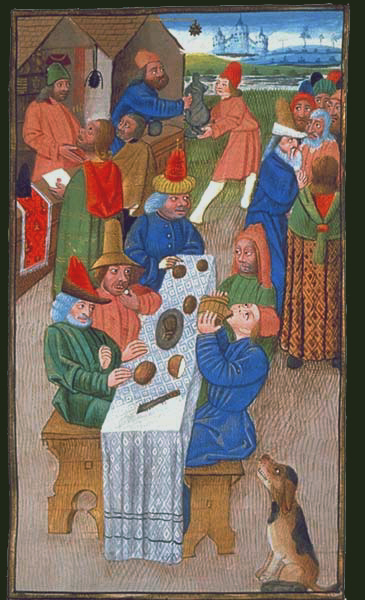

To Play

For those who didn’t enjoy street fun, there were home entertainments. For example, blind man’s buff and “Frog in the Middle.” The rules of the latter game were as follows: a person sat in the center while others taunted and hit them. The goal was to catch one of the players without leaving the circle, and then that person became the “frog.”

There were also calm games: some required players to answer questions from the leaders truthfully, while others involved telling a story. In addition, there was a game called “Saint Cosmas”: one participant took on the role of the saint, and the others knelt before them one by one. The leader had to make the kneeling player laugh by any means, and then that person had to perform some task.

By the Middle Ages, checkers, chess, dice, and even cards had become popular. Chess was a pastime for the nobility, and chessboards made of wood or metal were considered luxury items, often true works of art.

The rules for playing cards varied. For example, one participant would draw a card from the deck, and everyone present would bet money on it. If three or four cards of the same suit were drawn in a row, the player who drew the first card would win all the money bet on it.

But the most popular game was dice. This game was enjoyed by all social classes — in huts, castles, taverns, and even monasteries — with people losing money, clothes, horses, and homes. Many complained that they had lost everything they owned in this game. Moreover, there were frequent cases of cheating, especially with fake dice: some had magnetic surfaces, others had the same side reproduced twice, and others had a side weighted with lead. As a result, numerous disputes arose, sometimes even escalating into private wars.

To Go to the Bathhouse and Have a Good Drink

In most medieval cities, there were public bathhouses. In Paris at the end of the 13th century, there were 26 bathhouses, half a century later in Nuremberg — 12, in Erfurt — 10, in Vienna — 29, and in Wrocław — 12. Visiting a bathhouse was not limited solely to hygiene; rather, it was a place for entertainment, pleasure, and socializing. After bathing, visitors participated in receptions and dinners, played ball games, chess, dice, drank, and danced.

In German cities, wine merchants rolled wine barrels to the streets near the bathhouses, set up stools around them, brought out mugs, and offered wine to anyone who wanted to try it. An immediate drinking party would form on the street, so city councils were forced to ban this custom. Exceptions were made only for a few days a year, such as St. Martin’s Day when it was customary to open new wine. But on those days, people stood, sat, and lay in the streets — drinking wine.

Despite prohibitions from the authorities and the church, some bathhouses and adjacent taverns took on the character of brothels: in addition to food and drink, citizens could also enjoy massages and services from prostitutes, who were often referred to as “bath attendants.”

In general, although prostitution was condemned by the church, it was considered an inevitable phenomenon. “Women’s houses,” or “reputable houses,” belonged to noble families, merchants, royal officials, and even bishops and abbots, and the most prestigious of them were often located near the magistrate’s or courthouse. In the High Middle Ages, visiting a brothel by unmarried men was not considered shameful — it was seen rather as a sign of health and well-being.

To Rest by the City Fountain

Not all townspeople could afford to have a separate garden or water feature built behind their home; many lived in rented rooms, cubicles, and annexes. Water for household use was drawn from a public well or fountain located in the square, usually not far from the church. In the Late Middle Ages, these fountains served not only as decorations and sources of drinking water but also as meeting places and promenades for the townspeople.

To Watch an Execution

An execution site could be located outside the city, across the moat, on the square, or even in front of the victim’s house, but the execution was always a public event. The place and time of the execution, as well as the route of the criminal, were known in advance to all townspeople. Heralds summoned the spectators. The optimal time was considered to be noon, and often the authorities held executions on market days to ensure the maximum crowd, although not on religious holidays.

The crowd gathered around the criminal gradually as the procession moved through the city.

The entire punishment ritual was designed for spectators, a slow theatrical performance meant to involve the surrounding public in the ceremony. In some cases, the criminal was given the right to duel with the executioner, and people could assist in their release. This happened in Saint-Quentin in 1403 when, during the struggle, the executioner fell to the ground, and the townspeople demanded that the royal provost release the victor. Spectators monitored the precise execution of the ritual and could demand a retrial if something went wrong.

The bodies of criminals were forbidden to be buried in cemeteries, and their corpses remained on the gallows for many years until they completely decomposed, serving as a warning to those wandering around.