The recent Disney Shogun series reminded us of the West’s fascination with the major myth from Japan: the samurai. A proud knight, entirely devoted to his daimyo (lord). This myth was revealed to the West in the last third of the 19th century, with the country’s opening to foreigners, the wave of Japonisme, and the spread of works by Hokusai, the master of prints, the first to use the term “manga” in the sense of “derisory image” or “quick sketch”, where he would sometimes depict these warriors walking alone in magnificent landscapes.

It is no coincidence that George Lucas came to Akira Kurosawa’s aid, abandoned in Japan, to produce Kagemusha in 1979. His dark and stellar Darth Vader, who had conquered the world two years earlier, owed much to the samurai of the Japanese master and the warrior code – bushido – illustrated in Kurosawa’s films that young Lucas had admired during his studies.

Obscure Political System

This masterpiece, Kagemusha, opened with the famous Battle of Nagashino in 1575, which marked the twilight of an era lasting two and a half centuries, the same one traced by the Disney series. The wild time of civil wars, of clans sharing a fragmented medieval Japan.

Wild? Not quite. In a paradox typical of Japan’s complex history, it was marked by the simultaneous emergence of what, to Western eyes, embodies Japanese culture. First, ikebana, or the art of making flowers live, a composition invented before Buddhist altars as an offering.

It spread among these warlords to highlight their ceramics imported from China and their interiors already equipped with tatami mats and shojis, sliding paper-covered partitions. Then nô, also originating from religion, evolved into a theater of warrior gestures, while kabuki would become an urban and bourgeois theater in the 17th century, with civil peace restored. Finally, chanoyu, the tea ceremony, imported from China, was also a scene of political negotiations, one of whose masters was none other than Oda Nobunaga, the victor of the Battle of Nagashino.

When the Jesuits, following the Portuguese and the future Saint Francis Xavier, landed after 1550 on the island of Kyushu in the south of the Archipelago, they tried to decipher the rather obscure political system of this country: “The emperor, who has his own court, installed since the 5th century, son of the Sun goddess and the Moon lord, is a kind of pope who embodies spiritual power,” summarizes Julien Peltier. “In parallel, the shogun, established in the 12th century, is a weak king who establishes a military regime over a central third of the country. He is sometimes a great patron. Like little kings at the head of a fief or clan, the daimyo, the sword nobility, who share a community of values, often richer than the lords of the shogun’s court, divide the territory, feigning to recognize his sovereignty.”

Hierarchical Carnival

It is these daimyo and their clans who will battle each other, even threatening the shogun if one of them gains a lasting advantage. But in this incessant instability, which lasts until Nagashino and the end of the 16th century, the sacred existence of the emperor was never questioned by these warlords, suzerains with power over vassals, controlling territories sometimes as large as two or three French departments, who had often gotten rid of the shugo, the shogun’s local representative.

And the samurai? Their emergence, around the 9th-10th centuries, on the margins of the empire, especially in the east of the main island, results from the emperor’s failure to form a peasant infantry in the Chinese style, analyzes Julien Peltier. Employed by the shoguns, who imposed a military regime in the 12th century, and then by the daimyo, they would long embody the barbarian, the brute, in a still Sinocentric country with Confucian values.

It is very gradually that they would become civilized until, after 1603 and the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate, which remains peaceful until 1868, they became a kind of armed civil servants.

To this time of civil wars, marked by the construction of spectacular fortresses, sometimes magnificently decorated, also accompanied by an increase in production and international exchanges, historians have given the name “world upside down”.

For these upper warrior layers, the daimyo, “are incapable of maintaining themselves as a cohesive social group. Phenomena of social ascension or collapse are rapid and frequent. This hierarchical carnival also leads to the birth of autonomous villages, independent, free cities, grouped into leagues, compared to Italian cities of the Middle Ages.

Mastery of Firearms

Oda Nobunaga, the first to be able to reestablish a central state, was himself a small warlord, son of a daimyo, leader of the Oda clan, in the east of the country, near Nagoya. He burst onto the Japanese scene dramatically in 1560: with 3,000 men, he surprisingly defeated the powerful Imagawa house, which had assembled ten times more troops. It took him ten years to gain control of the central province of the country, Mino.

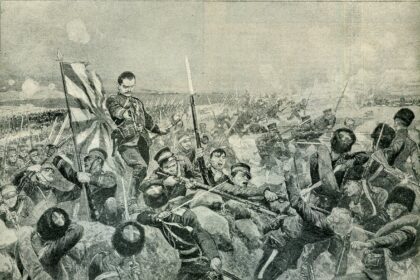

Called to help by the Ashikaga shogun, who had just been overthrown, he reinstated him in Kyoto, then deposed him, before fighting the famous Battle of Nagashino in 1575 against the last resisting clan, the Takeda clan: “A despised character, eccentric, almost mad, iconoclastic, Nobunaga is the first of the three unifiers, with Hideyoshi and Ieyasu, who would need three decades, until 1603, to reestablish a central authority,” summarizes Julien Peltier.

He relied on the mastery of firearms, arquebuses, which his infantrymen used in rolling fire, with several aligned ranks, devastating the samurai, equipped only with their swords. Imported by the Portuguese in 1543, but already smuggled in by Chinese pirates, the arquebuses were improved and manufactured by the Japanese, which deterred Europeans from invading their archipelago. Nobunaga also symbolizes openness to the outside world.

Moreover, with the Jesuits and their missions, a nanban culture emerged, influenced by Europe: Japan discovered bread, wine, geography, clocks, the organ and the viola, offered to Nobunaga, who positioned himself as a protector of craftsmen and merchants. He did not hesitate to burn down the country’s main temple, Enryakuji, to weaken religious forces.

His objective was to end the traditional shogunate, but he would not have time. Betrayed in 1582 by one of his treacherous generals, who surrounded him in a temple, he committed suicide there. Even during his lifetime, writes Souyri, he was already being worshipped. Even today, this extravagant lord, first founder of modern Japan, remains the source of inspiration for many novels and mangas.

Sakoku “Chained Country”