About 60,000 years ago, a mega-scale underwater landslide occurred off the coast of Morocco—the longest worldwide. It dragged about 162 cubic kilometers of mud and debris, more than 2,000 kilometers, into the Atlantic. The surprising thing, however, is that this underwater avalanche started very small and only grew to about a hundred times its volume during its course, as researchers report in Science Advances. Such rapid growth is not known from any other terrestrial landslide.

Mud and debris avalanches don’t just occur on land; there are also massive landslides underwater. Earthquakes, gas hydrates, or turbulence in submarine canyons can cause large sediment masses to slide off, especially on continental slopes, with catastrophic consequences. For instance, the Storegga Slide about 8,100 years ago caused large parts of the ice age Doggerland in the North Sea to sink. The previously longest underwater landslide was an avalanche that originated from the mouth of the Congo in 2020 and raced 1,100 kilometers into the Atlantic.

But how do such submarine landslides become mega-avalanches? For snow avalanches or landslides, it’s known how they develop and how much their volume can grow from beginning to end. For underwater landslides, however, this information has been lacking until now.

Underwater Landslide on a Megascale

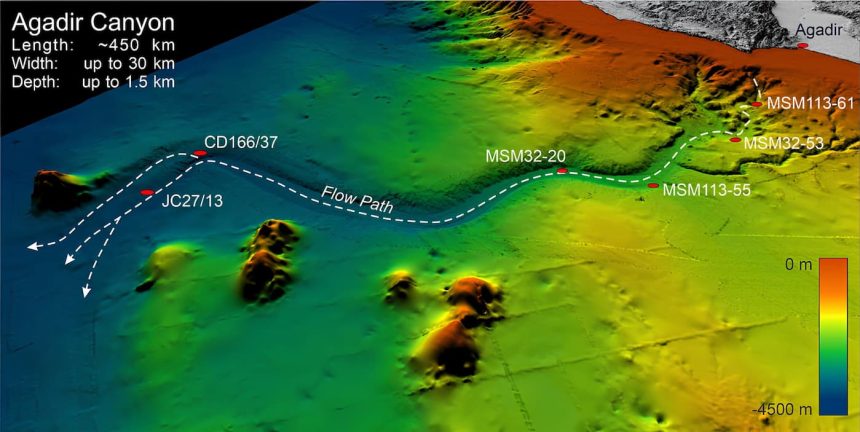

Now, for the first time, researchers have managed to reconstruct the growth of an underwater landslide in one of the world’s largest submarine canyons. The Agadir Canyon begins off the coast of Morocco and is 450 kilometers long and 30 kilometers wide. The gorge, deeply cut into the African continental slope, extends to a depth of 1,200 meters into the Atlantic. Geological studies have shown that large landslides have repeatedly occurred in this canyon.

One of the last and largest events of this kind was the so-called “Bed 5” landslide almost 60,000 years ago. “This suspension flow comprised about 162 cubic kilometers of sediment and covered the extraordinary distance of more than 2,000 kilometers,” report Christoph Böttner from the University of Kiel and his colleagues. To clarify where and how this underwater avalanche originated and how it developed, they analyzed more than 300 sediment cores from the Agadir Canyon and its surroundings and mapped the entire submarine canyon using sonar.

Favored by Bud, Speed, and Giant Canyon

The analysis revealed the gigantic extent of the Agadir landslide: It formed an avalanche about 200 meters high that raced into the depths at breakneck speed, dragging everything around it. “This landslide was the height of a skyscraper and raced down the slope at more than 65 kilometers per hour,” reports co-author Christopher Stevenson from the University of Liverpool.

“In the end, it covered an area larger than Great Britain under more than a meter of sand and mud.” The erosion traces are detectable over an area of about 4,473 square kilometers along the entire length of the canyon.

The enormous force and range of the underwater avalanche were made possible by a combination of several features. For one, the sediment slid off at a particularly high speed, giving the avalanche corresponding momentum.

For another, the seabed in this area consisted of fine, clayey mud. “The addition of mud increases the range and transport capacity even for coarser particles,” the researchers explain. This is because the fine particles remain suspended for a long time but simultaneously promote the cohesion of the suspension flow.

“Ultimately, the Bed 5 event was only limited by the cross-section of the canyon,” Böttner and his team explain. “Because this is exceptionally large, the landslide could become a catastrophic, massive event.”

Surprisingly Small Trigger

But where and how did this mega-landslide originate? Böttner and his colleagues were also able to clarify this. According to their findings, the trigger must lie in the southern part of the canyon tributaries—deeply incised, branched flow beds above the beginning of the gorge. There, the entire seabed could have detached in a closed layer up to 30 meters thick. According to the researchers, this large-scale but shallow slope failure could also explain why no clear traces are visible there.

The surprising thing, however, is that the trigger of the massive Bed 5 landslide was relatively small—it comprised only about 1.5 cubic kilometers. This means that the underwater avalanche must have drastically increased in volume from its beginning to its end. “This means that this landslide grew at least 100 times its original size,” report Böttner and his team.

Such an increase in volume is orders of magnitude greater than that of debris or snow avalanches on land.

Increased Risk for Coasts and Marine Infrastructure

According to the research team, the drastic increase in volume of this submarine landslide is not an isolated case: “We assume that this is a specific behavior of underwater avalanches,” says Böttner. “We have already seen similarly extreme growth in smaller landslides elsewhere.” However, the fact that even the largest events of this kind can have relatively small triggers is a new insight.

“Before this study, we thought that large submarine avalanches only originated from correspondingly large slope failures,” says senior author Sebastian Krastel from the University of Kiel. “Now we know that they can start small and then grow into extremely strong and extensive events.”