Insurrection of 10 August 1792: The Day Paris Rose in Revolution

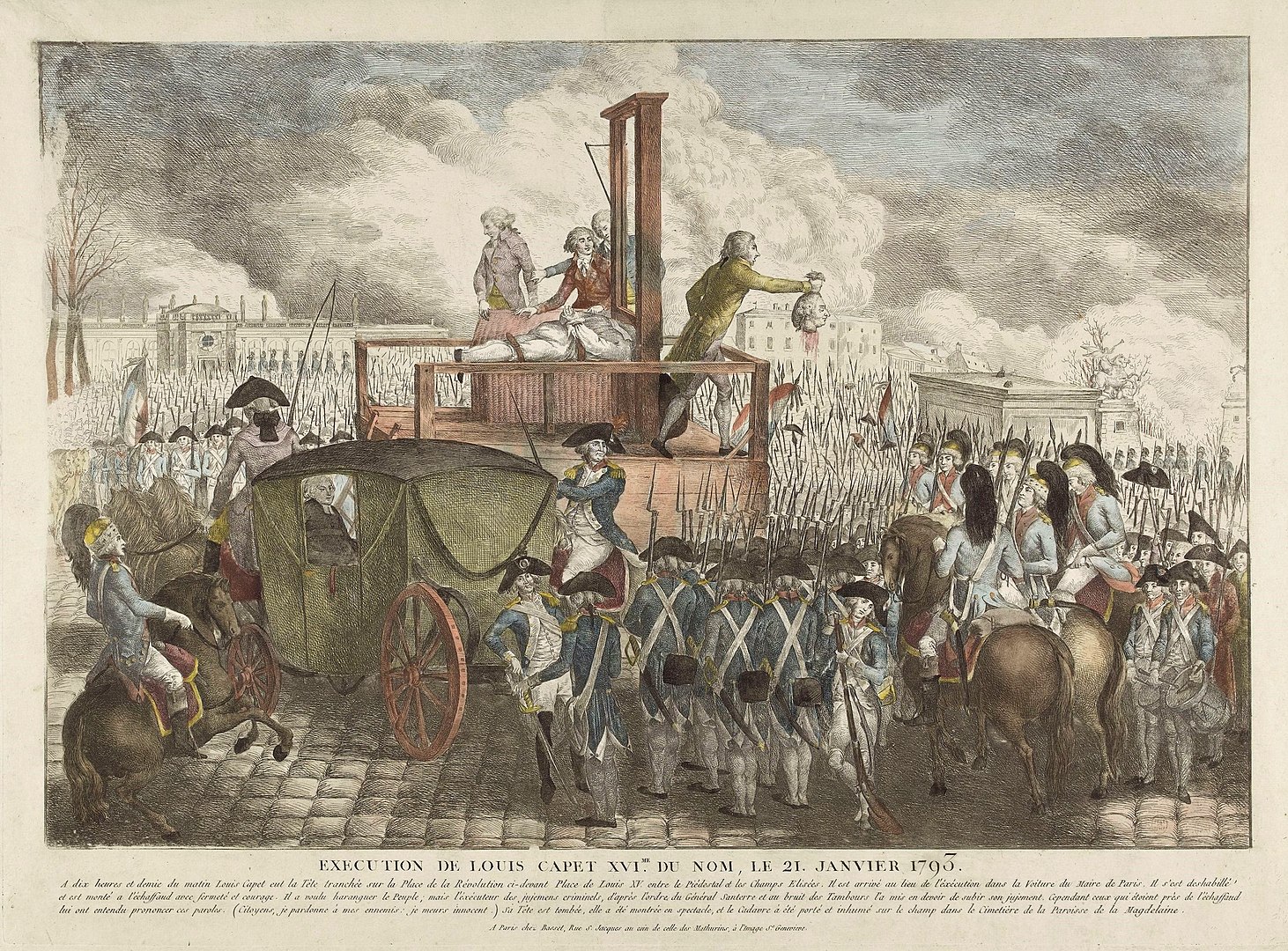

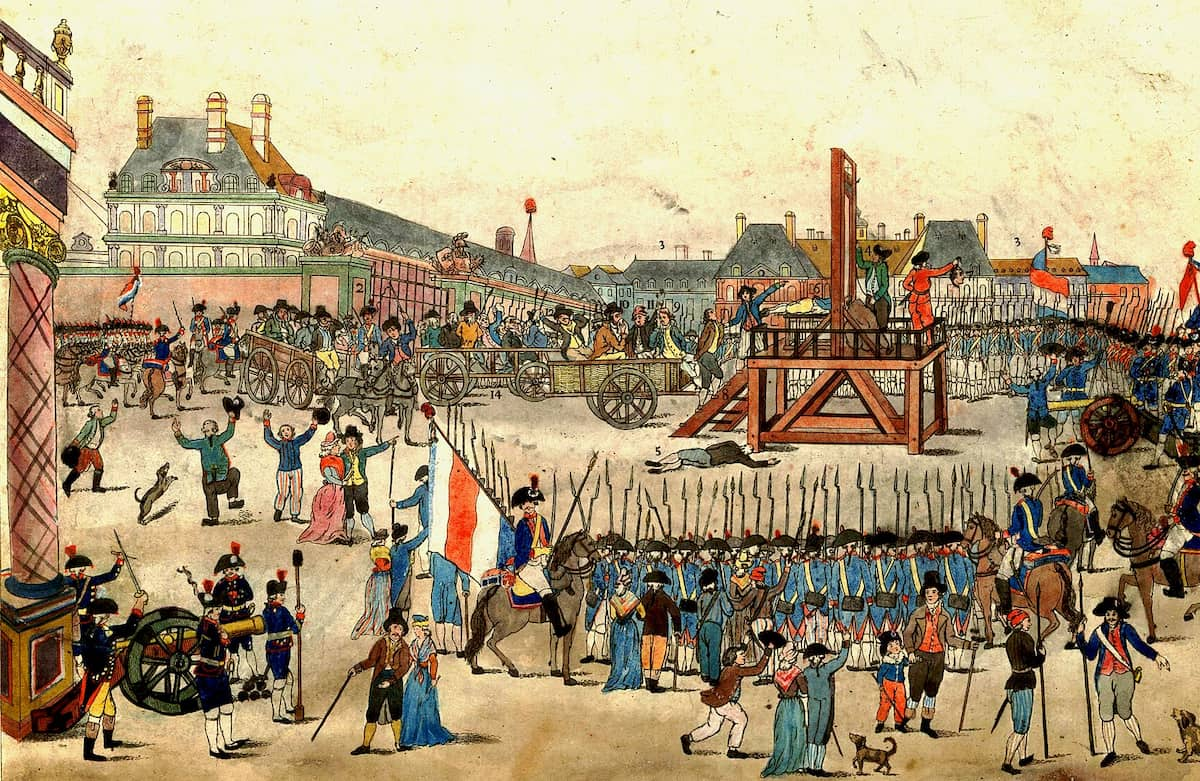

The Insurrection of 10 August 1792 was a pivotal event during the French Revolution when a mob of revolutionaries stormed the Tuileries Palace in Paris, leading to the fall of the monarchy and the imprisonment of King Louis XVI.