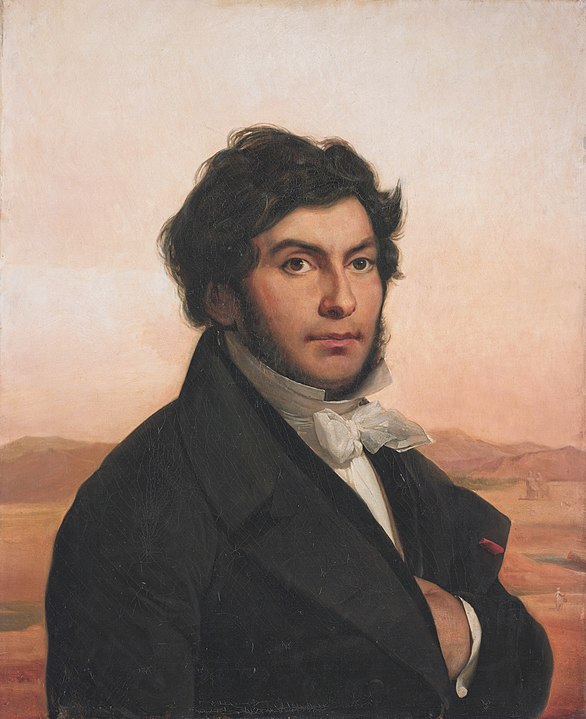

The Frenchman Jean-François Champollion, one of the most renowned Egyptologists of the 19th century, developed the first scientific system for deciphering hieroglyphs. He famously stated, “I am everything for Egypt and she is everything for me,” leaving an indelible mark on history beyond his scholarly contributions. A product of the Revolution and the Egyptian expedition, Champollion played a significant role in fostering a unique bond between Paris and Cairo, a relationship that persisted two centuries later. Revered as the Prince of Egyptophiles, his essential legacy is still evident in Paris, notably through the presence of an obelisk at the Place de la Concorde.

Jean-François Champollion: Genius of Ancient Languages

Jean-François Champollion was born on December 23, 1790, in Figeac. His father, a bookseller originally from Isère, held pro-revolutionary ideas, even favoring the Jacobins.

The seventh child of the family, Jean-François, was noted for his keen intelligence. Legend has it that he taught himself to read amidst the books in his father’s shop. With a fiery temperament, he didn’t always fit easily into the school system but he benefited from the support of his older brother, Jacques-Joseph.

The latter, passionate about history and archaeology, recognized the potential of his younger brother. Well-regarded among the elite of Grenoble (he would become friends with Fourier and Berriat), where he resided, he brought Jean-François to the capital of the Alps to oversee his education. The young prodigy proved too gifted for his brother to mentor, so he entrusted him to an abbot. It was during this time that the future Egyptologist learned Latin and Greek, as well as Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, and Chaldean.

In 1804, Jean-François entered the Imperial High School of Grenoble (now Stendhal High School) after passing the entrance exam with flying colors.

Note

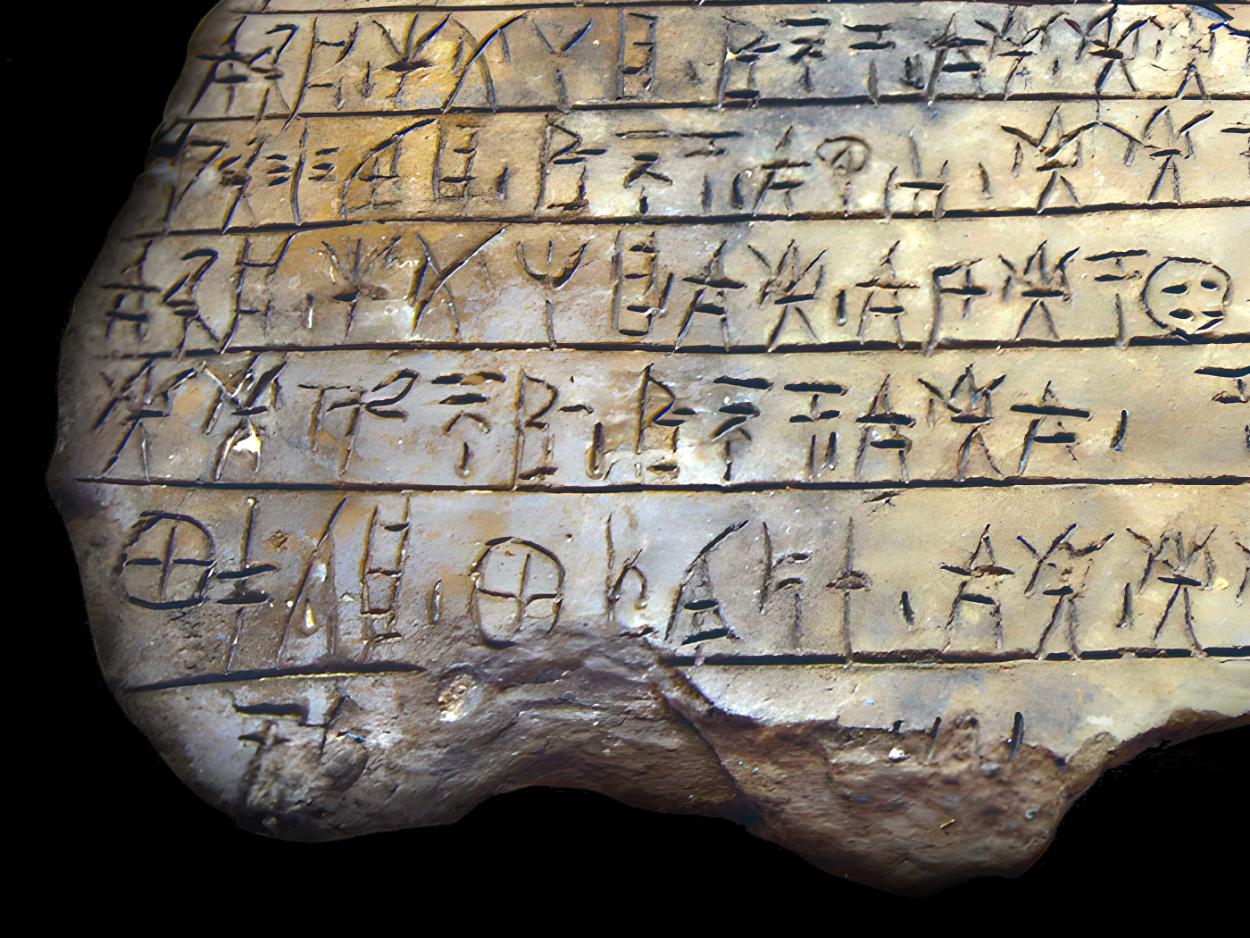

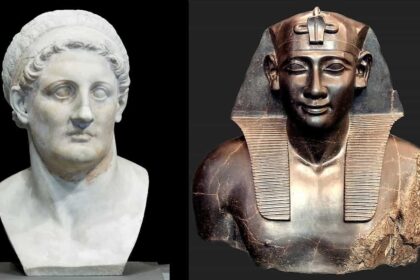

The Rosetta Stone is an ancient Egyptian artifact dating back to 196 BCE. It contains a decree issued by King Ptolemy V in three scripts: hieroglyphics, Demotic script, and Greek. Its discovery played a crucial role in deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

While he didn’t quite fit into the militarized organization of the institution, he thrived intellectually, deepening his knowledge of ancient languages and embarking on his first research projects. His brother, involved in the famous “Description de l’Egypte” (a collection of research and results conducted during the Egyptian Expedition of 1799), along with an encounter with a Greek monk passionate about the land of the Pharaohs, prompted him to delve into the mysterious hieroglyphs.

Jean-François, who was only 15 years old at the time, set out to conduct a thorough investigation into them. In 1807, he left Grenoble (after dazzling its Academy of Sciences) for Paris, where he hoped to find the resources necessary for his work. As a student at the Collège de France, he further refined his linguistic knowledge. Convinced that Coptic derived from the language of the ancient Egyptians, he quickly became one of the greatest European specialists before turning his attention to the famous Rosetta Stone and various papyri.

Champollion Deciphers The Hieroglyphics of The Rosetta Stone

At the age of 18, Champollion became a history professor at the University of Grenoble. Thanks to the political support of his brother, he was destined for a brilliant career. Alongside his teaching activities, Jean-François continued his research on hieroglyphics. A Greek text at the bottom of a stele brought back from Egypt by Napoleon Bonaparte‘s armies and previously studied unsuccessfully by Isaac Silvestre de Sacy and Thomas Young would change everything. With the help of the Rosetta Stone, on which texts in two languages (Greek and Egyptian) and three scripts (Greek, hieratic, and demotic) are inscribed, he formulated the fundamental hypothesis that the hieroglyphic system is both figurative symbolic and phonetic writing.

Despite his discoveries, Champollion would suffer from his own and especially his brother’s proximity to imperial circles. Jacques-Joseph, who during the Hundred Days had caught the attention of the Emperor himself (he had been his secretary during his stay in Grenoble), was gradually ostracized from political and academic circles after the Second Restoration. Jean-François, whose avant-garde theories and ego had earned him numerous jealousies, suffered the same fate, and both left Grenoble for Figeac. This exile to his childhood lands provided Champollion with the opportunity to perfect his work and improve his previously complicated financial situation.

By the end of 1817, he managed to return to Grenoble, taking advantage of the easing of political repression. Although just a librarian, he continued to attract attention both for his scientific activities and for his political opinions opposing the ultra-royalists. This led him to leave Grenoble once again for Paris in 1821. This year would be his greatest success.

Indeed, he then succeeded in deciphering the name of Pharaoh Ptolemy V from an inscription on the Rosetta Stone. The interpretation of Cleopatra’s name on the Philae obelisk followed this. Through a series of deductions and with a blend of intuition and logic, he established a value table for the various hieroglyphic signs.

On September 14, 1822, after exhausting work, Champollion was so convinced that he had unraveled the mystery of hieroglyphics that, overwhelmed by emotion, he suffered a mild attack (but nonetheless revealing the fragile state of health of this workaholic). Eight days later, he submitted to the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres a first summary of his discoveries. A summary of the hieroglyphic system would follow in 1824.

Champollion and Egypt: A Fatal Passion

The 1820s will see Champollion’s work receive the recognition he has long awaited. Benefiting from the support of scholars like Alexander von Humboldt (the famous German linguist and philosopher) and political figures, he manages, with the help of his brother, to finance a study trip to Italy. For his first departure from France, Jean-François goes beyond the Alps to scour libraries and museums, but above all the Egyptian collection of the king of Piedmont-Sardinia in Turin. There, he finds several pieces, notably from the 1799 Egyptian expedition, and accomplishes remarkable work, which earns him the interest of not only the Pope but also the King of France.

In 1826, Champollion was appointed curator in charge of the Egyptian collections at the Louvre Museum.

A consecration of a lifetime’s work, this position allows him to directly influence the development of nascent Egyptology. Enjoying a certain academic prestige, he convinces King Charles X to acquire several wonders, whether from the collection of the British consul in Egypt or from an obelisk from Luxor (offered by the viceroy Mehmet Ali), which now stands on the Place de la Concorde.

The Founder of Modern Scientific Egyptology

In 1828, at the peak of his career, Jean-François Champollion set sail for Egypt. After over 20 years of theoretical work, he would finally be able to see with his own eyes the monuments he had long dreamed of. Champollion, however, was a man who had grown weary from making sacrifices to advance his science at the age of almost 40. Egypt at that time was a remote country whose climate did not bode well for Europeans due to several endemic diseases.

Once again neglecting his health, the Egyptologist set out to verify on-site the validity of his theories on hieroglyphs. From his eighteen months of travel, he returned with an immeasurable mass of notes, documents, and notebooks, but also with a chronic illness (schistosomiasis?) that would eventually take his life.

Upon his return, Champollion, elected to the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres, took the lead as the very first chair of Egyptian antiquity at the Collège de France. He published four volumes of drawings and sketches on the monuments studied during his journey and completed his grammar and Egyptian dictionary, a masterful synthesis of his work. However, he would not have the opportunity to publish them himself (his brother would take care of that). He succumbed to an attack on March 4, 1832, at the age of 41, leaving behind an orphaned discipline but one with a promising future.