The Hundred Days constitute the final episode of the First Empire, from Napoleon I’s entry into Paris on March 20, 1815, to his second abdication on June 22, 1815. After escaping from the island of Elba and landing at Golfe-Juan on March 1, Napoleon Bonaparte crossed the Alps via a route now known as the “Route Napoléon.” The eagle’s last flight continued until he entered into the capital, garnering increasing enthusiasm from the population along the way.

He reclaimed power, left vacant by the fleeing Louis XVIII, for a hundred days. The defeat at Waterloo (Battle of Waterloo) forced him to abdicate for the second time on June 22. He was then exiled to Saint Helena.

—>Dissatisfaction with the Bourbon Restoration, a desire to regain power, and reports of political and military unrest in France motivated Napoleon to escape from Elba and return to France in 1815.

The 100 Days

Napoleon was certainly bored with the ‘little kingdom’ granted to him by the Treaty of Fontainebleau during his first abdication. Despite his efforts to enhance the Island of Elba and increase its resources, he felt confined in this tiny state. Accustomed to traversing Europe and dictating its laws, he found himself constrained. The political situation in France presented an opportunity for his return.

Napoleon’s boredom was compounded by the sorrow of losing all hope of seeing his son and wife, Marie Louise, whose infidelity he knew. This sorrow was only slightly mitigated by the presence of his mother and sister and the brief visit of Marie Walewska with her son. However, Napoleon likely would not have left his derisory kingdom, already resembling a prison under the constant surveillance of British Commissioner Campbell, if other, more compelling reasons had not urged him. These reasons were linked to both the internal French situation and the international scenario.

In France, the benefits of peace after over twenty years of war did not erase the original stain of the Restoration, which was brought back with foreign intervention. The former soldiers (grognards), many of whom had been discharged and reduced to half-pay, akin to near destitution, were naturally not in favor of a regime change while their former adversaries enjoyed positions of power. Young officers, facing seemingly blocked career paths, were impatient.

The empire’s nobility, overtly scorned by the Old Regime’s nobility, remained silent but missed the splendors of the defunct regime. Most significantly, the returning émigrés, having learned nothing from their long exile, fueled fears among buyers of national properties who anticipated being stripped of what they deemed legitimately acquired.

In brief, a profound discontent was rising within the population, endowing the former Emperor with a new nickname, “father of the violet,” symbolizing the hopes of his supporters. This flower heralded the return of spring. Napoleon closely monitored the French sentiment, receiving numerous emissaries from France and the Kingdom of Naples, where his brother-in-law Joachim Murat and sister Caroline still reigned.

Fleury de Chaboulon was one such emissary, but he was not alone. The information he conveyed to Napoleon was not as decisive as he claimed. Cipriani, Napoleon’s butler during the Hundred Days, made frequent trips to the continent, and other visitors came to the island, including a Grenoble merchant, the glover Dumoulin, who would later facilitate the Emperor’s return to France through the Alps.

The international situation prompted Napoleon to dream of escape. Russia, seeking a warm-water outlet, threatened British maritime supremacy; these two powers were already in conflict in Asia and the Middle East. The Russians’ claim to the protectorate of Slavic peoples clashed with Austrian interests in the Balkans.

Prussia was willing to cede its part of Poland to Russia in exchange for the disappearance of the Kingdom of Saxony, an ally of Napoleon until Leipzig. However, Austria, whose dominance over fragmented Germany would be compromised, opposed this arrangement.

France, slowly reintegrating into diplomatic affairs, aimed to restore the Bourbon rulers to Naples, displacing Joachim Murat. Yet, the English and Austrians were not inclined to betray their last-hour ally. Ultimately, two opposing groups emerged at the Congress of Vienna, with Russia and Prussia on one side and England and Austria, supported by France, on the other.

Europe stood on the brink of war once again. Napoleon was aware of this, receiving numerous messages from Vienna, notably from Claude-François de Méneval, attached to Marie-Louise; he could hope to play the role of mediator.

Getting Out of a Precarious Position

In any case, he had no choice. His financial situation was even more precarious as Louis XVIII’s government refused to honor the two million annuities granted by the Treaty of Fontainebleau. Additionally, the royal government funded henchmen to spy on the Emperor, even to the extent of attempting assassination.

The plot, orchestrated by Chevalier de Bruslart, a former Norman Chouan with connections to the Barbary pirates, failed, but the danger persisted.

Concerning England, uneasy about Napoleon’s proximity to the French coast, they demanded his deportation. Suggestions included Malta, deemed too close, the West Indies, the Azores, Australia, and finally, Saint Helena. Napoleon believed he could resist an abduction attempt for a while, but he knew that, with his limited resources, such resistance would only be a last stand.

He had likely been contemplating his return to France for a while. However, his escape was not premeditated; it was hastily organized. Key figures were only informed at the last moment, including the Emperor’s close associates and even family members.

Taking advantage of the absence of the Englishman Campbell, occupied in Libourne, they hurriedly prepared and executed the embarkation on the brig Inconstant. On February 26, 1815, a Sunday, after advancing the time for the mass, Napoleon bid a final farewell to the island, entrusting his mother and sister to the Elbois. The Imperial Guard only learned of the destination once at sea.

Some observers suspected the British of deliberately facilitating the Emperor’s departure to provide a pretext for his deportation. While this hypothesis has never been confirmed, certain events lean towards supporting it, such as the swift journey across France by an Englishman who proclaimed to the public that Napoleon had escaped, even before anyone else knew.

Napoleon Landed in Golfe Juan

The destiny favored the Emperor once again, who managed, with his small fleet, to elude the surveillance of the French cruise operating in the Mediterranean as well as the English corvette sailing nearby.

On March 1, 1815, the landing, initially planned in Saint-Raphaël, where Napoleon had departed a year earlier, took place in the vicinity of Vallauris, in front of bewildered customs officers, between two and five o’clock in the afternoon. The first bivouac was set up on the shore of Golfe-Juan, in a region that Bonaparte, a young officer, had traversed in 1794.

An attempt on Antibes, led by Captain Lamouret, who first set foot on the shore with 30 elite men, failed; 22 of the eight hundred soldiers from the island of Elba were captured by Colonel Cunéo d’Ornano, who commanded the place. This minor incident dissuaded Napoleon from taking the Rhône Valley route; he knew that the population of Provence was hostile, as evidenced by his passage in 1814, during which he had only escaped by disguising himself.

Therefore, he decided to march towards the Alps, following the indications provided by Dumoulin. He believed he could receive a warm welcome from a peasantry worried about the gains of the revolution. This change in route forced the Emperor to abandon two small artillery pieces that would have been difficult to drag through the mountains.

As Napoleon touched French soil again, another event unfolded at the other end of the country. General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes, leading the royal hunters, attempted to seize La Fère and its arsenal, while General Exelmans tried to incite rebellion among the troops of Guise and Chauny.

The Lallemand brothers participated in the enterprise that General Augustin Gabriel d’Aboville thwarted. The royalists saw the coincidence of these two events as an indication of a vast conspiracy.

However, the military uprising probably had no direct connection to the landing at Golfe-Juan; it is believed to have been orchestrated by republican circles subtly influenced by Joseph Fouché, perhaps to preempt the Emperor.

The small imperial troop reached Cannes, where they bivouacked near the chapel of Notre-Dame de Bonsecours. Cambronne was sent ahead to Grasse.

Between Cannes and Grasse, Napoleon encountered the Prince of Monaco; the two men exchanged a few words. “Where are you going?” asked Napoleon. “I am going home,” replied the prince. “So am I,” retorted the Emperor. Napoleon did not follow the road that now bears his name; it did not exist yet. This road intersects the path of that time in some places; in others, it deviates, and the old road is lost in the thickets.

The Flight of the Eagle

Here is a summarized account of the itinerary followed by Napoleon and his men: On March 2nd, they camped in the snow at an altitude of 1000 meters. Along the way, the Emperor handed a purse of gold to the mother of the deceased General Jean-Baptiste Muiron.

On March 3rd, they reached Castellane, where Napoleon encountered the sub-prefect removed by Louis XVIII but not yet replaced, continuing to Barrême in single file through the snow. On March 4th, after the cash boxes fell into a ravine, upon arrival in Digne, where the bishop expressed displeasure and proclamations were printed.

On March 5th, at Sisteron, the fortress could have halted their progress if the hesitations of royalist troops hadn’t left the passage open. It must be acknowledged, in their defense, that the landing was initially mistaken for the return of some weary veterans from the island of Elba.

In the evening, they reached Gap, where Napoleon received an enthusiastic welcome, paying for it with the abandonment of his flag. On March 6th, at Corps, the small group was reinforced by local peasants who escorted them, and some even expressed a desire to join. At La Mure, Napoleon commended the mayor for refusing to destroy the bridge.

On March 7th, at Laffrey, the Emperor advanced alone to meet the troop sent from Grenoble to stop him. The officer ordered him to fire, but the soldiers of the 5th regiment, refusing to obey, cheered Napoleon. Between Vizille and Grenoble, Colonel de la Bédoyère brought his regiment as reinforcements, and an imposing force approached the capital of Dauphiné.

The governor of Grenoble, General Marchand, was determined to resist; nonetheless, the gates were breached under the pressure of the crowd and soldiers.

Napoleon stayed in Grenoble for two days, from where he sent a courier to Marie-Louise, inviting her to join him, but in vain. He left Grenoble on March 9th to reach Bourgoin-Jallieu, where the illuminated city gave him an ovation despite the late hour (3 a.m.).

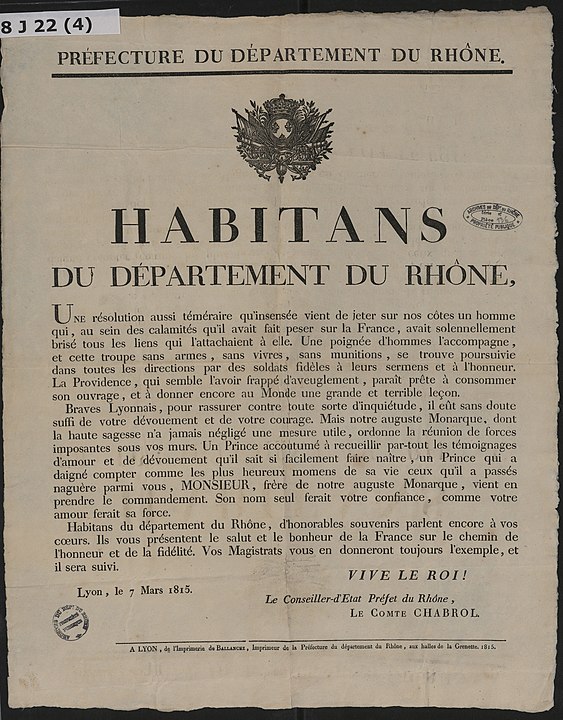

On March 10th, Napoleon reached Lyon; the Count of Artois, the Duke of Orléans, and Marshal Étienne Macdonald had been sent by Louis XVIII to defend the second city of the kingdom, but they could not oppose the tide.

Napoleon spent two days in Lyon, where he issued several decrees and a new letter to Marie-Louise. On March 13th, he arrived in Mâcon, expressing dissatisfaction with the city’s defense in 1814. On March 14th, he was in Châlons-sur-Saône, where a delegation from Dijon informed him of the expulsion of the royalist mayor and prefect.

The Hundred Days

The Emperor now behaves as if he were once again on the throne; he no longer merely issues proclamations and decrees but dismisses magistrates and officers, appoints others, and bestows decorations.

On March 15, in Autun, he learns of Marshal Michel Ney’s allegiance, who had promised the king to bring him back in an iron cage; he instructs the marshal to retain his command. He also confronts the royalist authorities of the city, accusing them of being led by the nose by priests and emigrants, and threatens to deal with them by hanging.

On March 16, in Avallon, General Jean-Baptiste Girard awaits him with two new regiments in a city adorned with the tricolor. On March 17, Napoleon arrives in Auxerre, where he reviews the 14th line of Colonel Bugeaud. On March 18, he writes a new letter to Marie-Louise and organizes the march on Paris, which the battalion from the Island of Elba will join by water coach; the Guard abandons the king and rallies to the Emperor. On March 19, Napoleon passes through Sens.

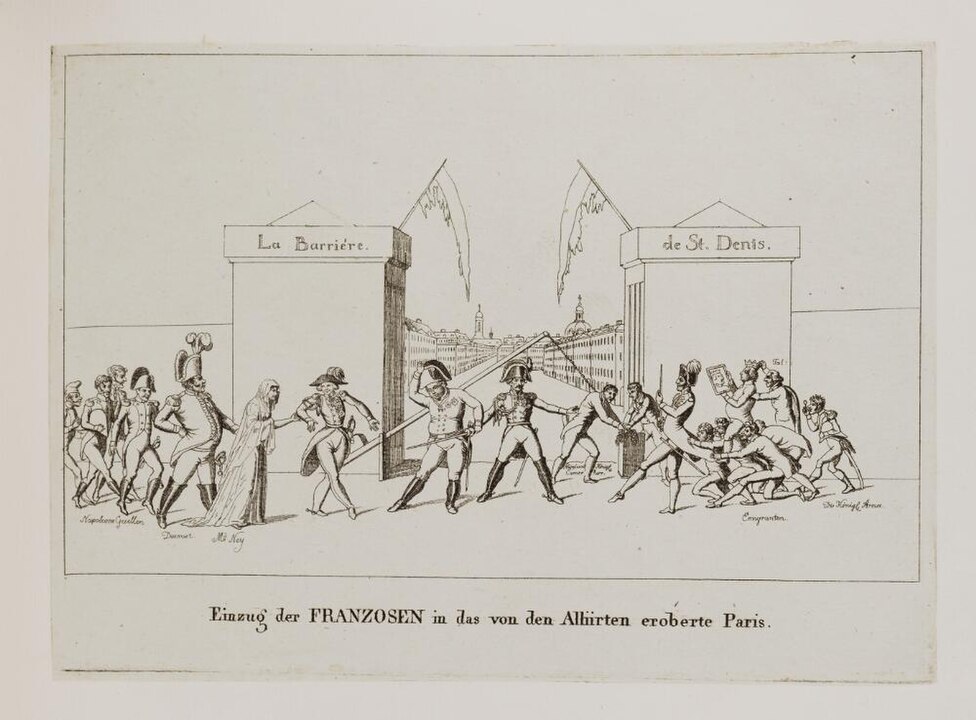

During the night, Louis XVIII leaves the Tuileries to move closer to the Belgian border. The Duke of Berry’s army, which was in charge of fighting Napoleon, disintegrates as a result of the officers’ desertions and the soldiers’ defection to the Emperor, who resides in Fontainebleau.

On March 20, Paris gradually fell into the hands of the Bonapartists. The tricolor flag is raised on public buildings. All that is awaited is the arrival of the great man. He arrives soon, and one of the witnesses to the scene of his entry into the Tuileries, carried in triumph by his supporters, General Paul Thiébault, believes he is witnessing the resurrection of Christ.

What lessons can be drawn from this fantastic reconquest of power without firing a shot? First, the common people and soldiers overwhelmingly approved the return of the Emperor. Second, with a few exceptions, the elites remained reserved, including senior officers, until the outcome was certain, and many of them remained loyal to the Bourbons. André Masséna, for example, who was in Marseille, remained on a prudent watch.

The Emperor, restored to his throne, did not regain his almost absolute power of yesteryear; he was far from it. He first had to overcome the last royalist resistance. The Duke of Angoulême, who was in Bordeaux during the landing, had raised an army in the south; this expedition failed, the prince was again exiled, and Emmanuel de Grouchy gained his marshal’s baton.

Napoleon then had to negotiate with the liberals; Benjamin Constant drafted additional acts to the empire’s constitution that gave the new regime a democratic appearance. Napoleon even abolished slavery, which he had reinstated in 1802.

Popular enthusiasm contrasted with the reservations and ulterior motives of the elites; the plebiscite that ratified the regime change met only relative success, given the numerous abstentions.

However, the Emperor’s pleas for peace did not sway his enemies’ opposition; Murat’s untimely commencement of hostilities in Italy, against his brother-in-law’s wishes, obviously contributed to maintaining the allies’ mood, but this senseless gesture was not decisive.

The decision to permanently remove Napoleon was already irrevocably made; Marie-Louise did not return. The war was inevitable. Thanks to the Emperor’s efforts, the reconstituted army was ready in June, but the nation as a whole was not. And the Hundred Days’ adventure ended tragically in the fields of Waterloo on June 18.

The second wave of emigrants returned, more ultra-royalist than ever. The thesis of a Bonapartist plot was endorsed. It legitimized the White Terror. Ney, Labédoyère, and Mouton-Duvernet were shot; Brune and Ramel, the latter deported to Fructidor as royalists, were murdered by fanatics; and General Gazan, who happened to be in Grasse during Napoleon’s passage, was deprived of command until 1830, a light punishment when so many others were in exile.

The Hundred Days contributed significantly to forging the legend of the Emperor; he became more popular than he had ever been. But for defeated France, condemned to see a large part of its territory occupied for 5 years and to pay indemnities of 700 million francs, deprived of the last conquests of the Revolution spared in 1814, this final fall, with the appearance of an individual apotheosis, was a true collective catastrophe.

Key Takeaways of Napoleon’s Hundred Days

- Exile to Elba: After his abdication in 1814, Napoleon was sent into exile on the island of Elba in the Mediterranean. The great powers of Europe granted him sovereignty over the island, but they kept a close eye on him.

- Escape from Elba: Taking advantage of the political instability in France and the discontent with the restored Bourbon monarchy, Napoleon escaped from Elba on February 26, 1815, landing in France on March 1.

- Supporters and March to Paris: Napoleon’s return to France was met with a mixed response. Many soldiers rallied to his side, and he began a march to Paris. The Bourbon king, Louis XVIII, fled the capital, and Napoleon entered Paris on March 20, 1815.

- Congress of Vienna Reaction: The return of Napoleon shocked the European powers, especially those who had signed the Treaty of Paris in 1814. The Congress of Vienna declared him an outlaw, and the Seventh Coalition against him was formed.

- Reforms: During the Hundred Days, Napoleon implemented several domestic reforms, including the Charter of 1815, which established a constitutional monarchy, and social and economic measures. However, these were not enough to secure his position.

- Waterloo Campaign: In an attempt to secure his rule, Napoleon launched a military campaign against the Seventh Coalition, which was led by the Duke of Wellington and the Prussian General Blücher. The campaign culminated in the Battle of Waterloo.

- Defeat at Waterloo: The Battle of Waterloo took place on June 18, 1815, in present-day Belgium. Despite initial successes, the combined forces of the British and Prussian armies defeated Napoleon. The outcome sealed his fate.

- Abdication and Second Exile: Following the defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon abdicated on June 22, 1815, in favor of his son. However, this abdication was not recognized, and he was forced to abdicate unconditionally on June 25. He was then exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic.

- Death in Exile: Napoleon spent the rest of his life in exile in Saint Helena, where he died on May 5, 1821. The cause of death was stomach cancer, although there have been theories and controversies surrounding his death.