In the Middle Ages, the knight was a horseback warrior, most often in the service of a king or a great feudal lord. The term “chivalry” evokes in our minds a whole dreamlike and fantastic universe that speaks to us of self-transcendence, honor, loyalty, generosity, and courtesy, which literature and then cinema have widely echoed. Mounted on a powerful steed, wearing a helm, and clad in steel armor, the knight, wielding the sword “of thrust and cut,” proudly displays his colors. Beautiful, loyal, valiant, and courageous, chivalry still testifies today to what the Middle Ages truly were.

- Germanic Origins of Chivalry

- Dungeons and the Castral Revolution

- The Knights of the Middle Ages: A Warrior Aristocracy

- Knight’s Weapons in the Middle Ages

- Warriors in Armor

- Role of the Horse

- The Knighthood Ceremony

- The Spirit of Chivalry in the Middle Ages

- Knights’ Tournaments

- The Christianization of Chivalry

- Bayard: A Model Knight

- The Decline of the Knights

Germanic Origins of Chivalry

The cult of weapons asserted itself within Germanic societies, which provided numerous recruits to the declining Roman Empire. For the Germanic peoples, to be free is to be armed, and the transition from youth to manhood is marked by a ritual described in a famous text by the Latin writer Tacitus:

Custom dictates that no one should take up arms until the city has recognized him as capable. Then, one of the leaders, his father, or his close relatives adorn the young man with a shield and a ‘framea‘: this is their toga; these are the first honors of their youth.

Marc Bloch identifies the roots of medieval chivalry (initiatory warrior brotherhood) in the practices of Germanic societies of the early Middle Ages.

Dungeons and the Castral Revolution

The terms “castrum” and “castellum” initially denoted structures of modest size until the close of the 10th century. Basic wooden keeps were erected on rocky elevations, river bends, marshland nuclei, or plains atop mounds of earth. With the adoption of stone circa 1050, the keep gained resilience, adorned with square towers featuring arrow slits. Typically comprising three levels, these houses housed a cellar for provisions on the ground floor, a spacious chamber for the lord’s valuables above, and a roofed platform where sentinels kept vigil.

While the keep offered sanctuary during perilous times, the lord and his household resided in adjacent edifices, encircled by a defensive palisade and a moat. Adjoining the master’s abode were stables, workshops, kitchens, and quarters for servants. The term “donjon” stems from “dungio,” derived from “dominus,” signifying the lord.

The governance of the medieval castle rested with a lord castellan endowed with the right of ban (military, policing, and judicial authority), which he exercised through a retinue of warriors stationed in the garrison. These “milites” constituted a corps of permanent professional combatants, marking an innovation in 11th-century chivalry.

A labyrinthine array of castles punctuated the landscape. Maine, boasting eleven castles in 1050, burgeoned to sixty-two by 1100; Poitou escalated from three to thirty-nine within the 11th century; meanwhile, Catalonia harbored eight hundred identifiable fortifications by 1050, a phenomenon historians term the “castellary revolution.” The tally of motte castles in France approximates ten thousand.

Despite attempts by Charles the Bald to proscribe these constructions in 864, citing detriments to neighboring inhabitants, such communities, beleaguered by insecurity, opted to endure the impositions of lordly authority in exchange for the protection afforded by fortified strongholds and their armed defenders.

The Knights of the Middle Ages: A Warrior Aristocracy

In medieval society, the knight is the bearer of the sword, the one who has the right and duty to be armed. He is the protector of the men and women of his community so that they may go about their occupations in peace. In Europe, the bearing of arms has been perceived since ancient times as the mark of those who claim their dignity by shedding their blood and risking their lives. The prestige of the weapon makes the one who carries it a separate being with specific rights and duties.

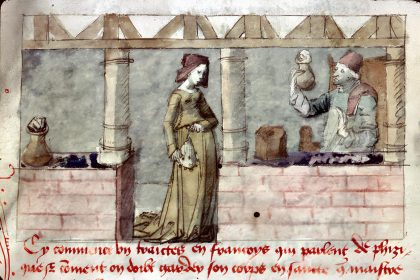

Among the knights, there are princes, dukes, and counts, but also men of modest origins: serfs and peasant commoners who have distinguished themselves because of their courage and loyalty to a noble in danger. Many epic poems recount these deeds. The lord looks after and feeds these “milites castri”; they are a part of his household.

Others are “chased”; they receive lands intended to provide for their maintenance. Ministerial, identifiable serf knights can achieve social ascent (for example, through advantageous marriages). The younger sons of minor nobility must seek their fortune at the point of the sword, as they cannot claim their father’s inheritance.

From the 11th century on, knights were expected to integrate into the ranks of the nobility, except for those already belonging to it. The merger between knights and nobility occurs later; it is necessary to wait until the 13th century in Lorraine and the 14th in Alsace to observe it. However, from the 13th century onward, chivalry closes in on itself, as the aristocracy wants to reserve the privilege for its sons. Chivalry then presents itself as the community of noble warriors opposing the “foot soldiers” without faith or law.

A professionalization of the warrior emerges, with changes in combat techniques requiring specialization. In heavy cavalry, tactics are based on breaking through the enemy’s front. The charge is made at a gallop, with the lance wedged under the arm and lowered horizontally, unlike the lance throw, which can only be used once.

Knight’s Weapons in the Middle Ages

If javelins and pikes continue to be used by infantry, the knight’s lance is frequently cited in the literature, including epic poems, lays, and novels, extolling chivalric life. This lance, equipped with a wooden shaft, gradually extends to reach four meters and weighs nearly twenty kilograms. A stopper prevents the hand from slipping during impact.

In the 15th century, a hook was affixed to the armor to secure the lance and cuirass together, easing the burden on the lance bearer (known as a knight-banneret), as the weight could increase due to the pennant, standard, or even the banner, which identifies the fighter and serves as a rallying point in the midst of battle. When the lance breaks, the sword must be drawn!

The most commonly used offensive weapons are the lance and the sword, followed by axes, war hammers, flails, and daggers. Among the latter, “the mercy stroke” bears an eloquent name: its short and thin blade can penetrate the gaps between the metal pieces of the hauberk and helmet. The crossbow is such a fearsome weapon (its bolt pierces armor through and through) that the Council of 1139 forbade its use among Christians, to no avail. The great Welsh longbow, with an even faster rate of fire, wreaked havoc on French armies during the Hundred Years’ War.

A close combat weapon (used for face-to-face combat), the sword of the 11th and 12th centuries is massive, measuring a meter long and weighing over a kilogram. It is called a thrusting and cutting sword because it strikes with both the tip and the double-edged blade. The handle, made of wood or horn covered with leather, and the round pommel designed to improve balance vary in elaborateness depending on the wealth of the owner.

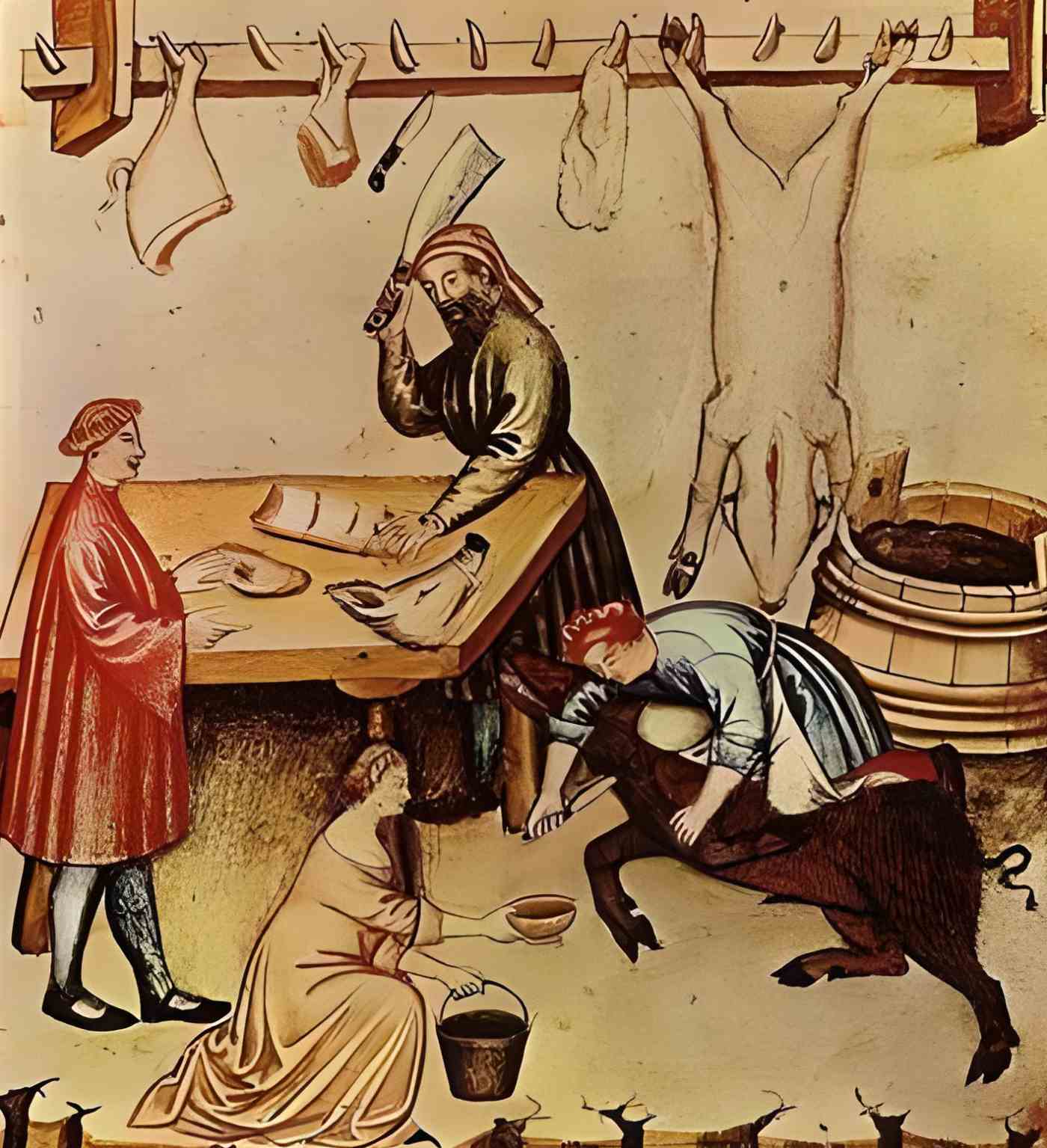

Crafting a good and beautiful sword that is elastic and resistant requires up to 200 hours of work. This sheds light on the blacksmith’s status.

The brogne, a sturdy leather tunic reinforced with metal scales, served as the most typical form of protection until the middle of the eleventh century. Then the mail coat or hauberk, became highly valued. Made of interlocking iron rings of varying thickness and tightness (depending on cost), it protects the body down to the knees, with limbs covered by mail leggings and sleeves. Under the hauberk, a padded gambeson is worn to cushion blows and friction. A fabric coat of arms is worn over it, displaying the fighter’s heraldry.

Warriors in Armor

From the 13th century onwards, the protection of the body was reinforced by applying metal plates to the chest, arms, and back, intended to make it more difficult for weapons to penetrate (a blow from an axe or a crossbow bolt could pierce a hauberk). This assembly became more rigid, leading in the 15th century to the grand white harness, a complete armor made of more effective, heavier, and more expensive articulated pieces!

The knight’s head is protected by a helmet, the “heaume” (from the Germanic “helm”), a simple hemispherical cap reinforced with a nasal guard from the 11th century onwards, then with a ventail or visor pierced with eye slits. In the 12th century, the helmet became closed and cylindrical, with two narrow horizontal openings for vision and ventilation holes underneath. With the articulated visor, it evolved towards the “bassinet.” On the helmet a crest bears the knight’s heraldic symbol, adding weight to the helmet, which is only put on during combat.

The shield completes the protective equipment. The Norman model, almond-shaped, is made of wood covered with leather but cumbersome; it is replaced by the variously shaped targe on which the knight’s arms are painted.

Role of the Horse

The warhorse, the destrier (held by the right hand of the squire), must be sturdy and resilient, capable of charging at a gallop and withstanding the press of the melee. It stands above the palfrey, used for traveling, and the roncin, a pack horse carrying the warriors’ gear. A knight must possess several destriers because it is not uncommon for his mount to be killed in battle, despite mail coverings intended to protect it. The complete equipment of the knight costs considerable sums, and many knights cannot afford to meet these expenses, so they seek the aid of a powerful lord by entering his service.

Hunting in the Middle Ages was seen as training for war, both psychologically and physically, as the wild fauna of medieval forests could severely test even the most determined hunters, providing an opportunity to assess their mastery and endurance. The warrior’s training begins with hunting, as well as with horsemanship and horse care.

The Knighthood Ceremony

After a long and rigorous apprenticeship experienced alongside the aspirants of his age, the young squire is welcomed into the community of knights. It is the greatest day of his life: that of “knighthood” (which means in medieval French to equip).

During this ceremony, the young boy, thanks to the weapons he receives, crosses the threshold that separates the status of a child from that of a man. This ritual is described in epic poems:

Then they dressed him in very beautiful attire. And they laced a green helmet on his head. Guillaume girds the sword on his left side. He takes a great shield by the handle. He had a good horse, one of the best on earth.

Before receiving the weapons, he will perform a sanctification gesture known as the accolade, which involves striking the recipient with the right palm of the person doing the dubbing. This is a symbolic test to see if the young man can withstand a blow without flinching. Thus inaugurated, the new knight must demonstrate horseback riding skills, then, at a gallop, strike down with a lance in the center the dummy mounted on a pivot meant to represent the enemy.

Next comes the banquet, where the father, uncle, or lord shows generosity, which is a sign of chivalrous spirit, by entertaining their guests, not forgetting the poor, the jugglers, and the jesters who will extol the virtues of their benefactor.

The Spirit of Chivalry in the Middle Ages

The chivalry has its own code of honor, based on loyalty, courage, and often devotion to a lady (referred to as courtly love). Courageous in combat and faithful to his lord (or his king, or his lady), such is the image of the valiant knight.

However, the knight remains primarily a warrior, and the church (like the people) often bears the brunt of private wars. That is why it tries to make the lives and actions of the knights moral, who soon receive the mission to protect those who pray and those who work. The knights thus transform into soldiers of God.

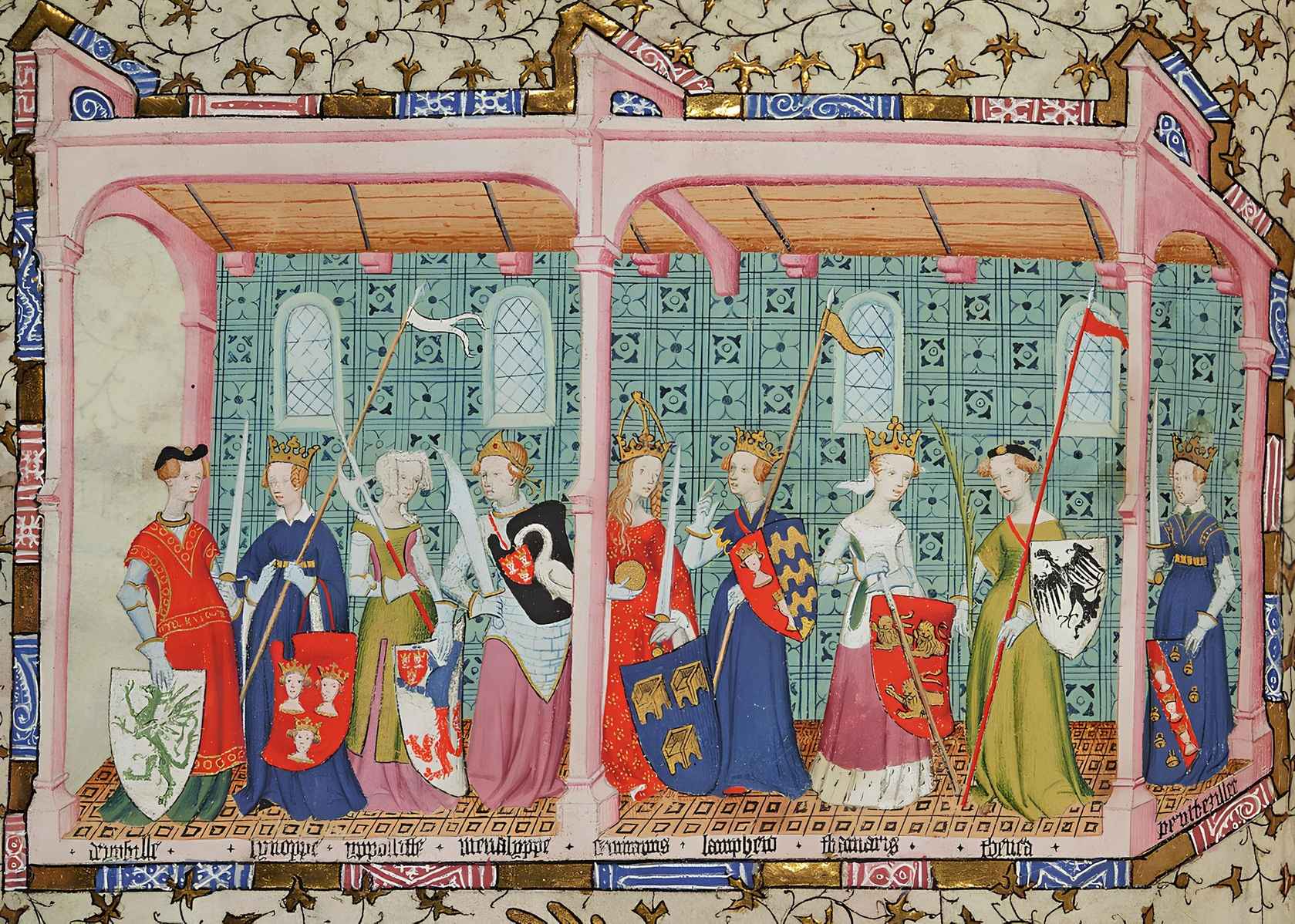

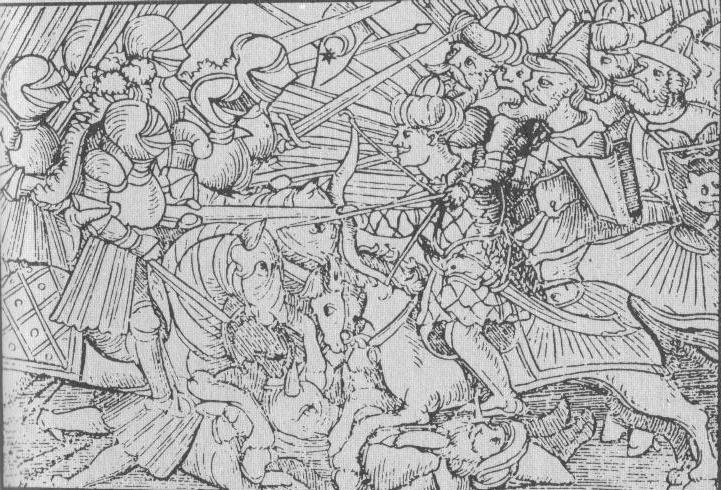

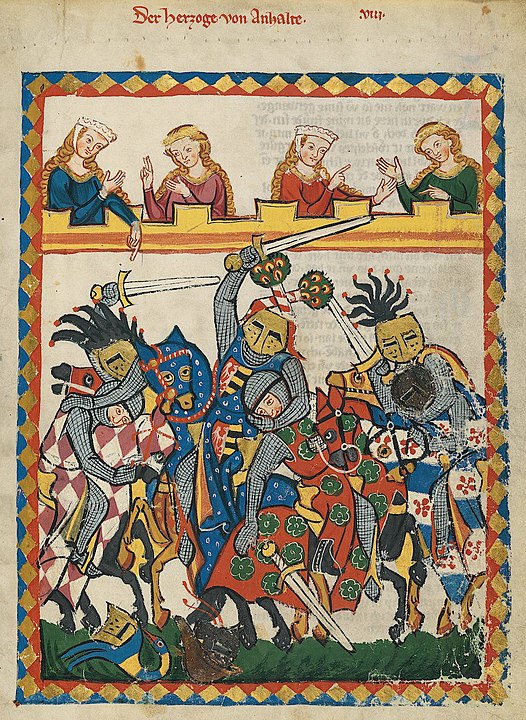

Knights’ Tournaments

The freshly dubbed knight must travel the world to gain experience and demonstrate his valor. He will find in the practice of tournaments the opportunity to distinguish himself and make a name for himself (vital for knights of modest origins) to find a protector to rise within feudal society. These tournaments are highlights of chivalrous life; they serve as grand maneuvers during which one trains for war.

Two camps form according to affinities, family ties, and provincial origins. At the signal, the two troops launch against each other in combat whose rules resemble those of a real battle; wounded and dead are collected at the end of the confrontation, while prisoners are ransomed.

In these tournaments, beautiful ladies and noble maidens crowd the stands, adorned in their finest attire, to witness the battles. If one of them entrusts her colors to a fighter, he must win or die. Life is hard for the knight!

The Christianization of Chivalry

Originally, the Church unequivocally relied on scripture (Matthew 26:52, “All who take the sword will perish by the sword” and “if a catechumen or a faithful wants to become a soldier, let him be sent away because he has despised God”). This condemnation persisted over the centuries, imposing severe sanctions on any man who killed one of his own.

However, the church had to take into account the necessities implied by an increasingly intimate coexistence with the state. When the Germanic invasions raised concerns about the future of the Empire, the clergy had to denounce the militant incivility that declared antimilitarism represented. Thus, through the words of Saint Augustine, the theory of “just war” emerged.

“The soldier who kills the enemy is like the executioner who executes a criminal; it is not a sin to obey the law. He must, to defend his fellow citizens, oppose force with force.”

Just war (and the mission to conduct it) became justified because the duty of the Christian prince was to impose by terror and discipline what priests were unable to assert through words. In practice, the demands of Christian doctrine became, against the pagan or the infidel, a holy war.

At the end of the 11th century, a formula was established, leading to the adherence of men of war: the Crusade. Its ideology was already present in Spain and Italy in the 9th and 10th centuries in the struggle between Islam and Christianity, but it reached its full extent when the Holy See announced a new objective: Jerusalem and the liberation of Christ’s tomb. The Christianization of chivalry is a phenomenon that has affected all of Christianity from the East to Northern Europe.

Bayard: A Model Knight

Entered into the service of King Charles VIII, the knight Bayard distinguished himself as early as 1495 at the Battle of Fornovo, during the Italian Wars. In 1503, his heroic defense of the Garigliano Bridge alone against 200 Spaniards to secure the French retreat earned him universal renown. His name also remains associated with the victory at Agnadello in 1509. He besieged Brescia with Gaston de Foix after deciding to take Bologna, but a pike blow during the assault seriously injured him.

He managed to stop the enemy army in Pavia for two hours with 36 men despite being under threat from the Venetians’ and Swiss’ superior forces. He also sustained a serious shoulder wound. He was in Artois in 1513 when the English invaded, and at Guinegate (the Battle of the Spurs), the English captured him. Released shortly after, he was appointed lieutenant-general of Dauphiné. After the battle at Marignano in 1515, King Francis I wanted to receive a knighthood from his hands.

In 1522, despite prodigies of valor, he could not prevent the defeat of La Bicocca in Lombardy. He was successful in getting the French army across the Sesia after defeating Romagnano, but on April 30, 1524, an arquebus shot fatally wounded him. Incarnated with courage and chivalrous spirit, he passed into posterity as “the knight without fear and beyond reproach.”.

The Decline of the Knights

The fortress linked to the history of chivalry is going to disappear, powerless to resist for long against repeated battery fire, and all military architecture is evolving. Proud walls must be abandoned in favor of low defenses “à la Vauban.”

The setbacks of French chivalry during the major defeats of the Hundred Years’ War (Crécy, Poitiers, and Agincourt) demonstrate the increasing power of artillery and infantry.

Time and history have done their work; chivalry has disappeared as an institution, but its ideals and models are still present. If chivalry is absent from society, is it also absent from the hearts of men?