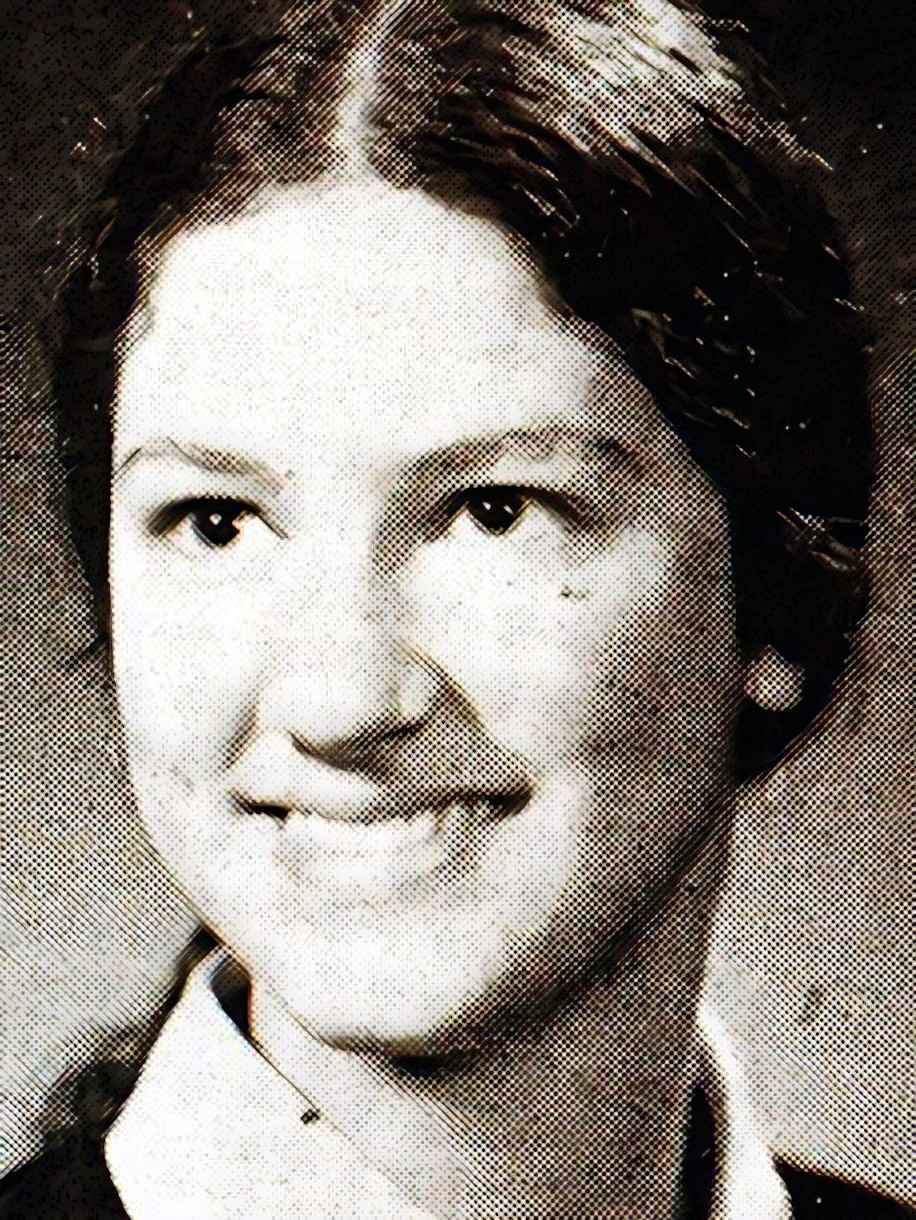

Laurel Blair Clark (March 10, 1961 – February 1, 2003), was an American astronaut who died in a shuttle accident while returning from the STS-107 mission on the Space Shuttle Columbia. Clark was a Flight Surgeon in the U.S. Navy before she became an astronaut. In 1987, Clark earned her doctorate in Medicine from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The United States Navy supported her through college and into her career as a Navy Medical Doctor in 1989, and she also went on to become a qualified Diving Medical Officer and Submarine Medical Officer.

Laurel Clark at a Glance

Submarine service was Laurel Clark’s prior choice, but due to quotas for female soldiers, she transferred as a medic in 1991. Clark joined NASA as a member of Astronaut Group 16 and underwent training as a Space Shuttle Mission Specialist beginning in 1996.

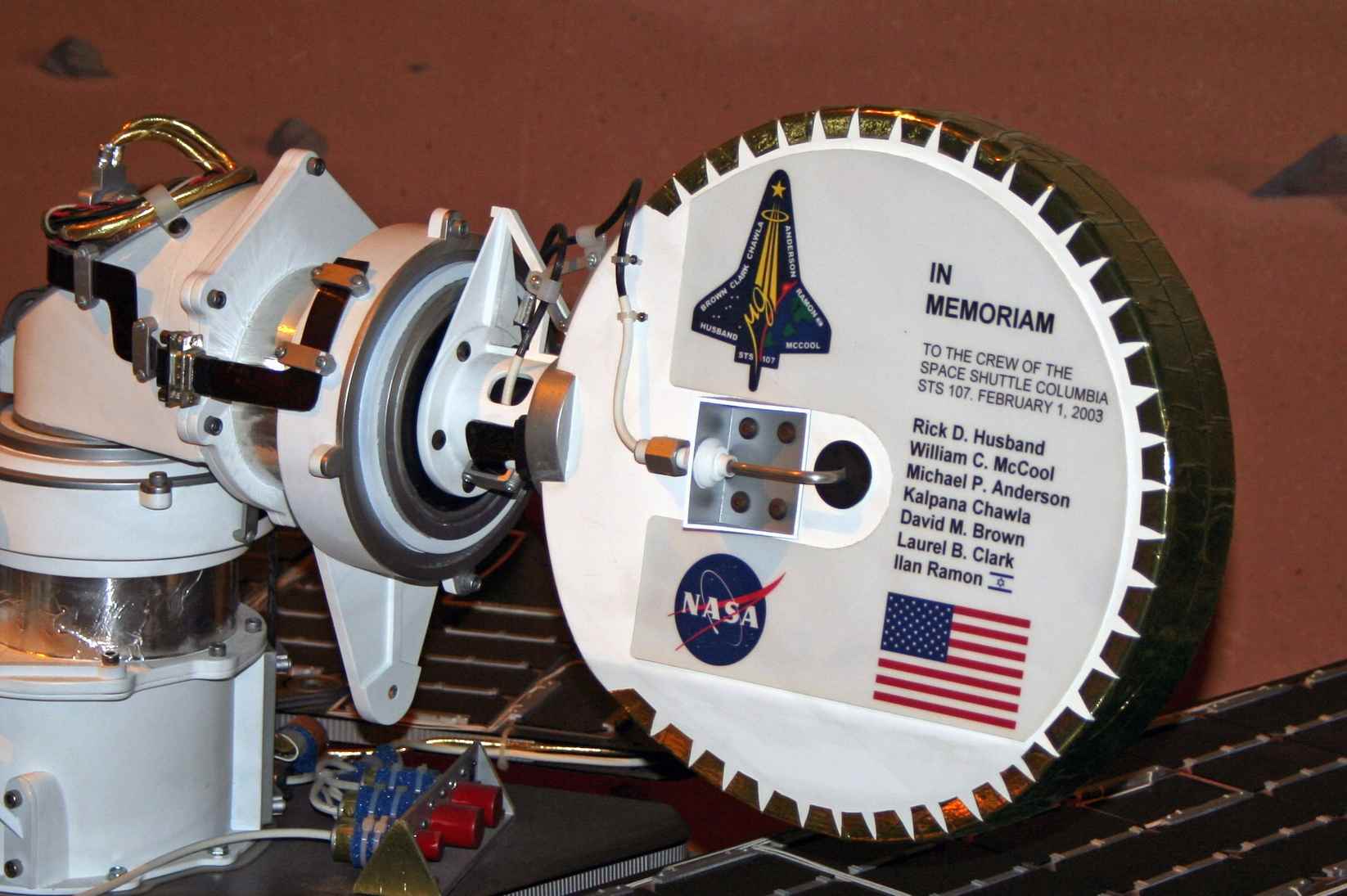

Clark and six other astronauts boarded the Space Shuttle Columbia on January 16, 2003, for mission STS-107. On February 1, 2003, while returning to Earth, the shuttle exploded, killing all seven crew members.

The United States government and civil society observed a period of grief and commemoration after Clark’s death, and the Navy posthumously promoted her to the rank of captain.

Researchers have named asteroids, lunar craters, and Martian peaks after Laurel Clark, and U.S. President George W. Bush presented her with the Congressional Space Medal of Honor together with six others. Buildings in Clark’s native community and at the medical centers and universities where she worked bear her name now.

Laurel Clark’s Earlier Years

Laurel Clark was the oldest of three siblings (Lynne, Daniel, and Jonathan Salton). She was born on March 10, 1961, in Ames, Iowa. Her family tree included Scottish ancestors. Clark was a small child when she and her family relocated from California to New York State and then to Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Her parents, Robert Salton and Margory, split up when she was a teenager, and she and her two brothers, together with their stepfather Richard Brown, and five step-siblings, relocated to Racine, Wisconsin, that same year.

Clark later began to consider this area to be her true home.

Clark attended the University of Wisconsin – Madison after graduating from the public William Horlick High School in Racine in 1979. She considered herself a “boring student with straight A’s,” but she was always fascinated by “the environment, ecosystems, and animals,” so she got her Bachelor of Science in Zoology in 1983 and her Bachelor of Medicine in 1987.

A Medical Career in the Armed Forces

Laurel Clark joined the Naval Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (NROTC) to receive financial aid from the Navy while she was pursuing her bachelor’s degree in medicine. In the meantime, Clark enlisted in the Navy’s Experimental Diving Unit, Division of Diving Medicine, to train for active duty. After that, she graduated with a medical degree from the university in March 1987.

After that year, Clark did an internship in pediatrics at the Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, for a year. She completed diving training at the Naval Diving and Salvage Training Center (NDSTC) in Panama City, Florida, and the Naval Undersea Medical Institute (NUMI) in Groton, Connecticut, after her internship in 1988.

After completing her military medical officer training in 1989, Clark relocated to St. Jerome’s Bay, Scotland, where she supervised the medical section of a submarine squadron and was responsible for undersea medical care and radiation health.

During this period, she conducted multiple emergency medical evacuations from submarines and dove alongside Navy divers and SEAL teams. She joined the Navy as a Diving Medical Officer and Submarine Medical Officer two years later.

Laurel Clark was highly frustrated by the fact that women were not allowed to serve in submarines in the United States Navy at the time. There was “no place” for her to sleep aboard a submarine. When she asked two commanding officers to let her join a submarine for a 24-hour training trip, they still said no.

However, Clark was persistent, and by offering to sleep in the medical room of the submarine, she was finally able to take part in the mission. After two or three trips, Laurel was forced to leave. Determining to become an aviation medic, she spent six months in 1991 at the Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida, learning aviation medicine and how to fly a helicopter.

Laurel Clark was sent to the Western Pacific many times to carry out missions in hostile conditions after she completed her training as an Aviation Medic with the AV-8B Marine Attack Squadron 211 (VMFA-211). Her squad won the honor of “Marine Corps Attack Squadron of the Year” for a successful mobilization at one point.

After serving as an Aviation Medic with Marine Aircraft Group 13, Clark was sent to Pensacola to join the VT-86 advanced jet training squadron. She was a Basic Life Support Instructor and Advanced Trauma Life Support Provider while serving in the military and was certified by the National Board of Medical Examiners.

She was also an expert in the use of hyperbaric oxygen chambers and advanced life support techniques. The Aerospace Medical Association and the Society of U.S. Naval Flight Surgeons were two professional organizations in which Clark participated.

Laurel Clark’s Expertise in Space

Laurel Clark applied to join NASA in 1996, and in April of that year, she was chosen among the NASA Astronaut Group 16. Clark was already pregnant when she became a lieutenant commander. On August 12 of that year, she and the other 34 members of her class reported to the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, to begin their space training.

Clark spent the years between July 1997 and August 2000 working in NASA’s Astronaut Office on spacecraft payloads and habitability after completing two years of training to become a Shuttle Mission Specialist and being certified to fly. Clark’s first space mission was STS-107, which she was chosen for in September 2000. This would be her first time in space.

After many postponements, the 2001 launch date for Space Shuttle Columbia’s STS-107 mission was moved to 2003. At 10:39 a.m. EST on January 16, 2003, Clark and six other astronauts (Rick Husband, William C. McCool, Michael P. Anderson, Kalpana Chawla, David M. Brown, and Ilan Ramon) launched from the Kennedy Space Center onboard Columbia. During an interview before her departure, Clark said:

“We’re incredibly lucky to be able to be working where we are up above the Earth and being able to see our planet from that vantage point.”

Laurel Clark, STS-107 Interview.

The Experiments Clark Conducted in Space

The crew conducted at least 80 different experiments for the mission. Since Clark had a background in medicine, she was excited to participate in the mission’s life science research. Her background as a military doctor was invaluable to the team.

During the mission, Clark took part in several biochemical and physiological experiments investigating how the human respiratory system reacts to weightlessness and how the growth of bone and cancer cells is altered in microgravity. The European Space Agency created and tested this advanced respiratory monitoring system.

Laurel Clark’s side interest in space gardening was also useful throughout her expedition. She bred bacteria and yeast in microgravity and grew roses and silkworm moths to study the impact of microgravity on plant growth.

Clark had planned to take a lot of pictures in space, and after the trip, she sent her family an email to say how amazed she was by the beauty of space and that she had captured some really good shots:

“Hello from above our magnificent planet Earth. The perspective is truly awe-inspiring….I have seen some incredible sights: lightning spreading over the Pacific, the Aurora Australis lighting up the entire visible horizon…the crescent moon setting over the limb of Earth… Every orbit we go over a slightly different part of the Earth… Whenever I do get to look out, it is glorious. Even the stars have a special brightness. I’ve seen my ‘friend’ Orion several times. …I feel blessed to be here representing our country and carrying out the research of scientists around the world. …Thanks to many of you who have supported me and my adventures throughout the years. This was definitely one to beat all. I hope you could feel the positive energy that beamed to the whole planet as we glided over our shared planet. Love to all, Laurel.”

Mission Specialist Laurel Clark’s email to family and friends during STS-107.

She also had a video camera and recorded the moments just before the shuttle Columbia exploded. The footage shows the astronauts completing their last preparations for the return landing while smiling and appearing calm.

The video was at least 13 minutes long; however, the accident destroyed part of the footage. This footage was also the last clip recorded by the astronauts before the accident.

Laurel Clark’s Death

At 8:15 a.m. EST on February 1, 2003, Space Shuttle Columbia began to return to Earth after successfully completing its mission. At 8:44 a.m., Columbia re-entered Earth’s atmosphere, with an anticipated landing time of 9:16 a.m. At 8:53 a.m., while the shuttle Columbia was flying at 23 times the speed of sound 231,000 feet (70 km) over the California shoreline, the first signs of the disaster appeared.

At an altitude of around 200,700 feet (61,2 km) over Texas, contact with ground control was lost at 8:59 a.m. as the shuttle Columbia entered the atmosphere and began experiencing a series of pressure and temperature anomalies. At this point, there were 16 minutes left until the planned landing at KSC.

Those on the ground witnessed the returning shuttle explode into a plethora of tiny light spots and then produce a strong shockwave at nine in the morning. At this point, the ground team initiated the emergency plan and began searching for survivors.

The onboard data recorder captured a series of frightening sensor readings and failures on the left side of the spacecraft for 12 minutes after the shuttle entered the atmosphere as the intense heat of re-entry engulfed the spacecraft.

The total duration of the STS-107 mission was 15 days, 22 hours, and 20 minutes. NASA announced later that day that all seven crew members had died in the crash. After the Columbia disaster, U.S. President George W. Bush issued a speech notifying the public that “no survivors” had been found.

The next day, investigators found the remains of all seven astronauts and began the process of identifying them. According to a later study by NASA, all seven crew members lost consciousness within seconds of the space shuttle’s uncontrolled disintegration. They had all died in a matter of seconds. It is probable that the astronauts endured extreme trauma from rotational forces and their helmets not being head-conforming.

The astronauts died of a lack of oxygen due to the high-altitude environment and the uncontrollable fall of the space shuttle. Insulation material fragments that broke off during the re-entry and landed on the left wing of the shuttle caused damage to its thermal protection system.

On the journey back, the shuttle Columbia’s friction with the environment created a lot of heat, which eventually burned through its protective shell and caused it to disintegrate.

Laurel Clark’s mother and stepfather, Dr. Richard and Margory Brown, died in a car accident in 2019, 16 years after the bellowed astronaut’s death.

After the Disaster

After the incident, President George W. Bush issued a statement offering his sympathies to the families of the seven lost astronauts. National flags were lowered to half-staff at the Kennedy Space Center, the White House, and other official facilities.

Flowers and flags were placed at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida and the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Texas in memory of the astronauts who lost their lives serving their nation.

On February 4, George W. Bush and NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe attended a memorial ceremony in Houston honoring the seven astronauts who perished in the Columbia disaster.

Laurel Clark’s burial was conducted at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors on her 42nd birthday on March 10. Her last resting place was with the other victims of the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster. Following her death, Clark was given the honorary title of Captain.

Laurel Clark’s Personal Life

Laurel Clark was a member of the Unitarian Universalism theology, a branch of Unitarian belief, and he was active in the church of that group in Racine, Wisconsin. Her memorial marker at Arlington National Cemetery shows the Unitarian symbol.

Clark was an avid gardener, diver, skydiver, hiker, camper, and adventurer in her leisure time. She enjoyed tinkering with radios and earned her amateur radio license from the FCC in 1997, at which time she began using the radio call sign KC5ZSU (Her license was canceled in 2009).

In Florida in 1989, Laurel met Jonathan Clark, a scuba diver-in-training. Navy medic Jonathan Clark fell in love with Laurel at the conclusion of their training periods, but they were eventually sent in opposite directions in life.

While Laurel visited Scotland, Jonathan was fighting in the Gulf War (1990—1991).

After being married at Laurel’s church of choice, the God’s Church of Deliverance, in 1991, the couple moved to Florida, where they had their first child, Iain, in October 1996. When the shuttle disintegrated, the father and son were among the people waiting for it to land at Kennedy Space Center.

The ground staff took them away and broke the bad news to them after the disaster. Iain’s relationship with his mother was special, so much so that he told his father, after the tragedy, that he “wished we could build a time machine” so they could go back and save her.

After getting married, Jonathan became an aviation medic for NASA and eventually became the head of the medical team at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, where he also helped care for space shuttle astronauts. After the death of his wife, he attempted to withdraw from the public eye, but his efforts were fruitless.

Johnson relapsed into heavy drinking after that, but he pulled himself together for the sake of his kid. In 2004, Jonathan returned to aerospace and dedicated himself to improving spaceflight safety by investigating past shuttle mishaps like the Columbia catastrophe in order to prevent such incidents in the future.

In addition to working on the Advanced Crew Escape Suit, Jonathan Clark joined the International Association for the Advancement of Space Safety (IAASS), established in 2004 in the Netherlands, a year after the Columbia disaster.

Clark’s Commemorations and Awards

Laurel Clark was a Navy veteran and the holder of several medals and ribbons, including those for Astronaut, Air Medic, Submariner, and Diver. Three times in her life, she was awarded the Navy Commendation Medal, and she also got the Defense Service Medal and the Overseas Service Ribbon.

After her death in the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, Clark was posthumously honored with the Defense Department’s Distinguished Service Medal, NASA’s Space Flight Medal, and NASA’s highest honor, the Distinguished Service Medal.

Posthumously, Clark was one of seven astronauts to receive the Congressional Space Medal of Honor from then-President George W. Bush on February 3, 2004.

The names of the seven lost astronauts were written on the back of a monument to the Space Shuttle Columbia at Arlington National Cemetery. Similar memorials can be seen at the Kennedy Space Center and in Downey, California, today.

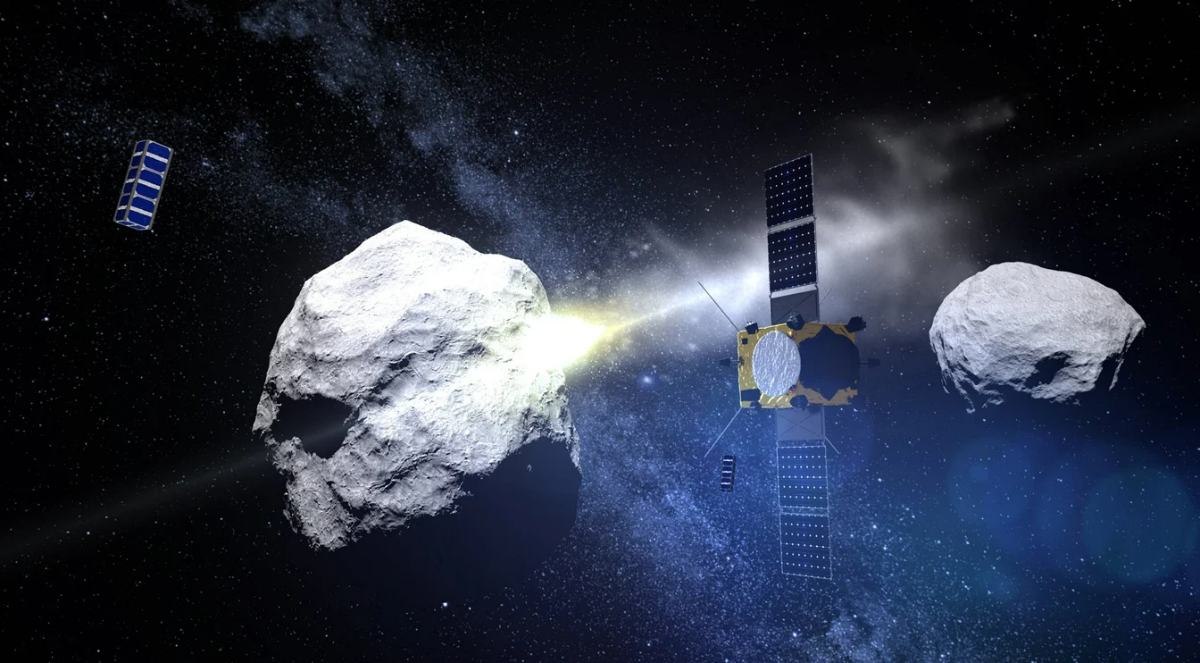

The names of the seven were inscribed on the Space Mirror Memorial at the Kennedy Space Center, and they were also etched on the rear of the antenna of the Spirit Mars Rover, which was launched in June 2003.

Columbia Hills and Mount Clark are the names NASA gave to a group of Martian hills that are close to the Spirit Rover’s landing site. Asteroid 51827 and the Clark lunar crater inside the Apollo Crater on the Moon are both named for her.

After Laurel Clark died in 2003, the Aerospace Medical Association also made her an Honorary Member. The association also established a survival foundation in her name. In the presence of Clark’s husband, Jonathan, Bethesda Naval Hospital’s (now the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center) auditorium received the name “Laurel Clark Memorial Hall” in July 2003, and the Naval Aerospace Medical Institute also established a survival foundation in her name in August 2004.

In honor of Clark and fellow Naval Flight Surgeon David Brown, who both perished in the Columbia disaster, the Naval Aerospace Medical Institute opened the Laurel B. Clark and David M. Brown Aerospace Medicine Academic Center in August 2004.

Racine, Clark’s birthplace, has a memorial fountain dedicated to her honor, with a plaque depicting Clark’s favorite constellation, Orion, and providing a short narrative of her life.

Clark had packed recordings from the Scottish band Runrig to play aboard the space shuttle, since she was a fan. After the shuttle disaster, Clark’s husband and son discovered the band’s CDs among the debris. The band’s 2016 album The Story has a closing tune titled “Somewhere” that features a recording of Laurel Clark speaking to Earth from outer space.