Around 1478, the Florentine painter and inventor Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) created the prototype of a tricycle vehicle which is called Leonardo’s Self-Propelled Cart today. The autonomous cart was powered by a spring motor. A functional replica model of this spring-propelled vehicle has existed since 2004 and it can be seen in several technological museums today. The Self-Propelled Cart is thought to be related to Leonardo’s research into perpetual motion machines and is only known through a drawing in his Codex Atlanticus. In a way, da Vinci invented the car more than 500 years ago because he was centuries ahead of his time. Only in 1770 could the Frenchman Nicolas Cugnot come up with the first steam-powered car.

Description of da Vinci’s Self-Propelled Cart

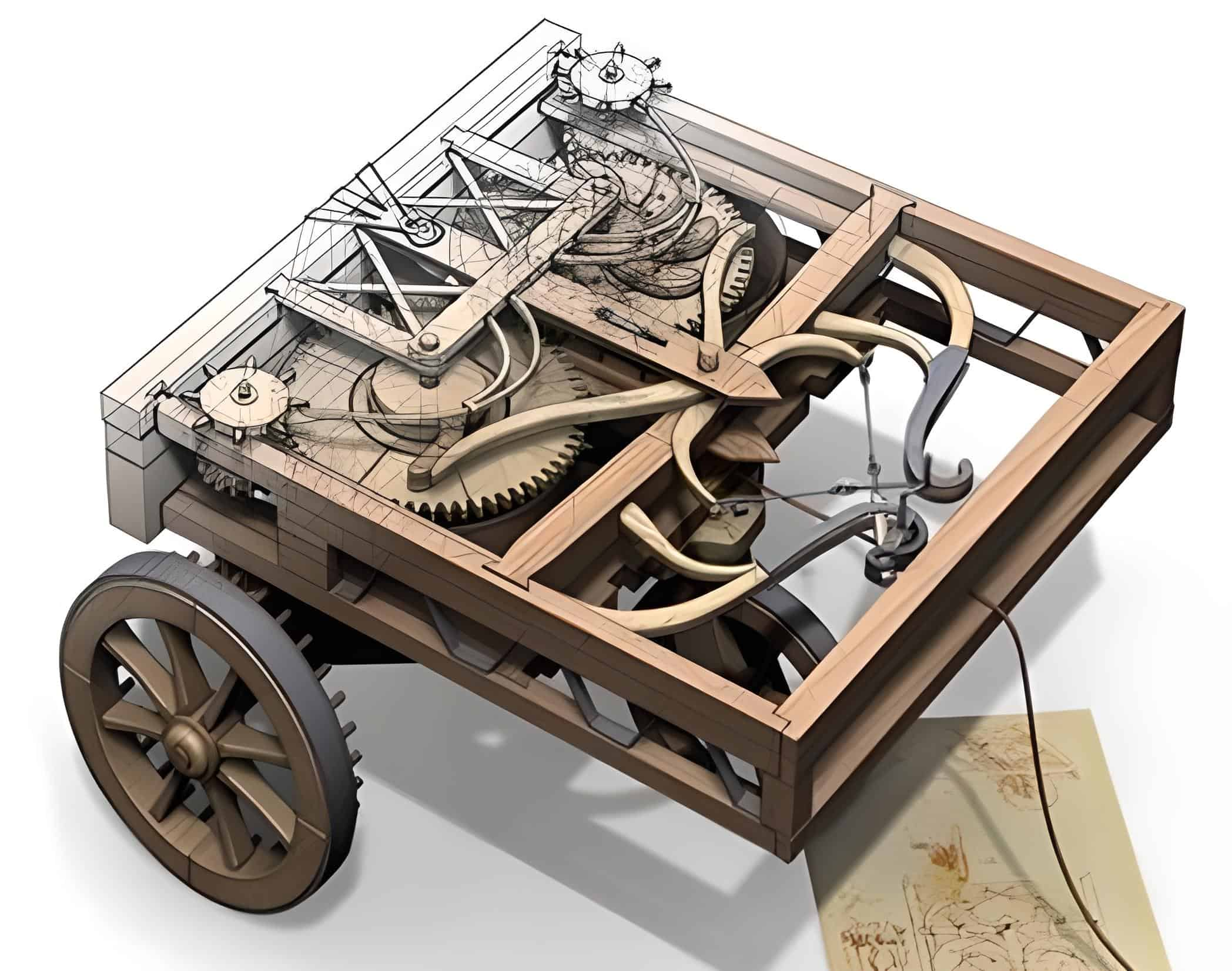

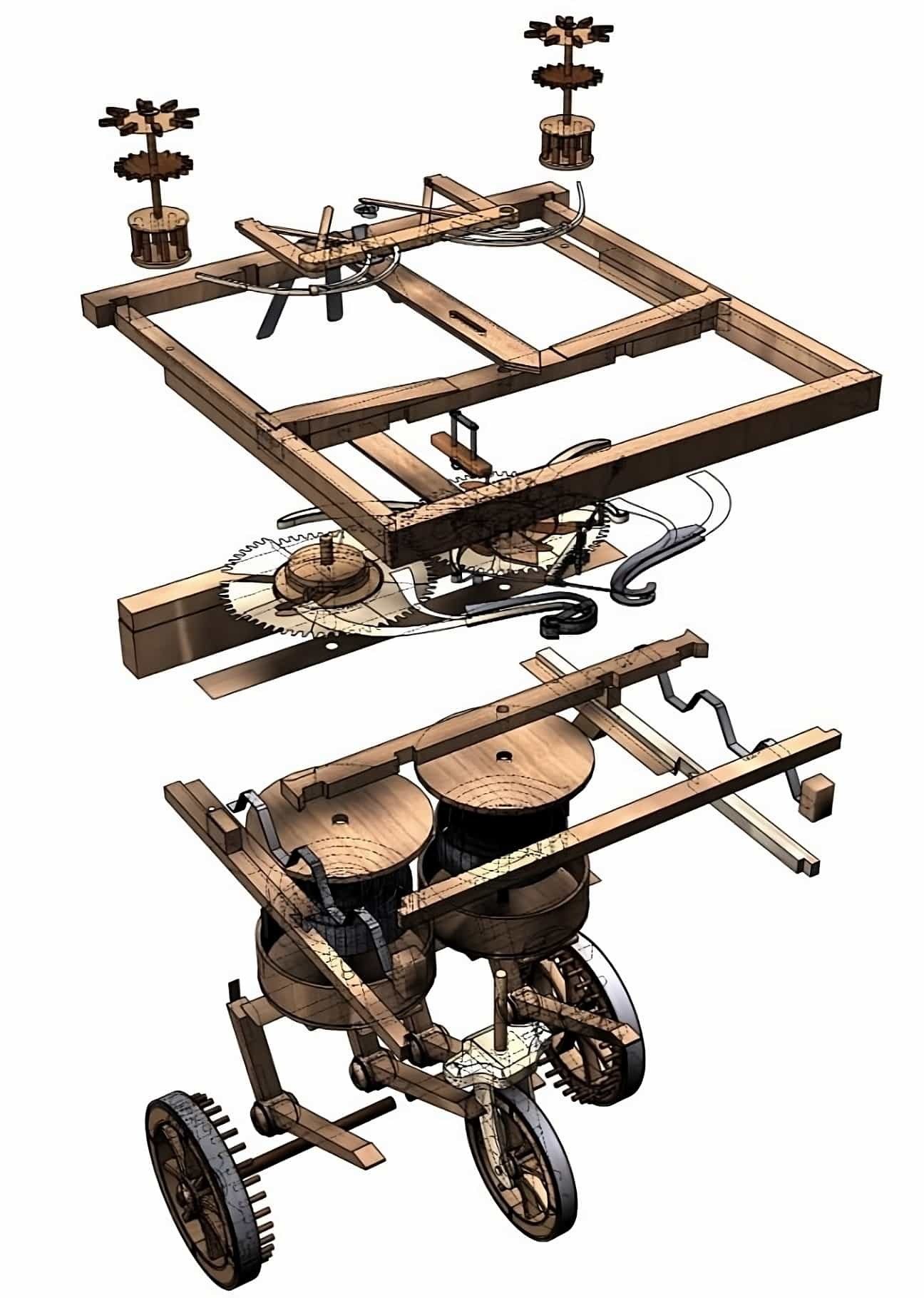

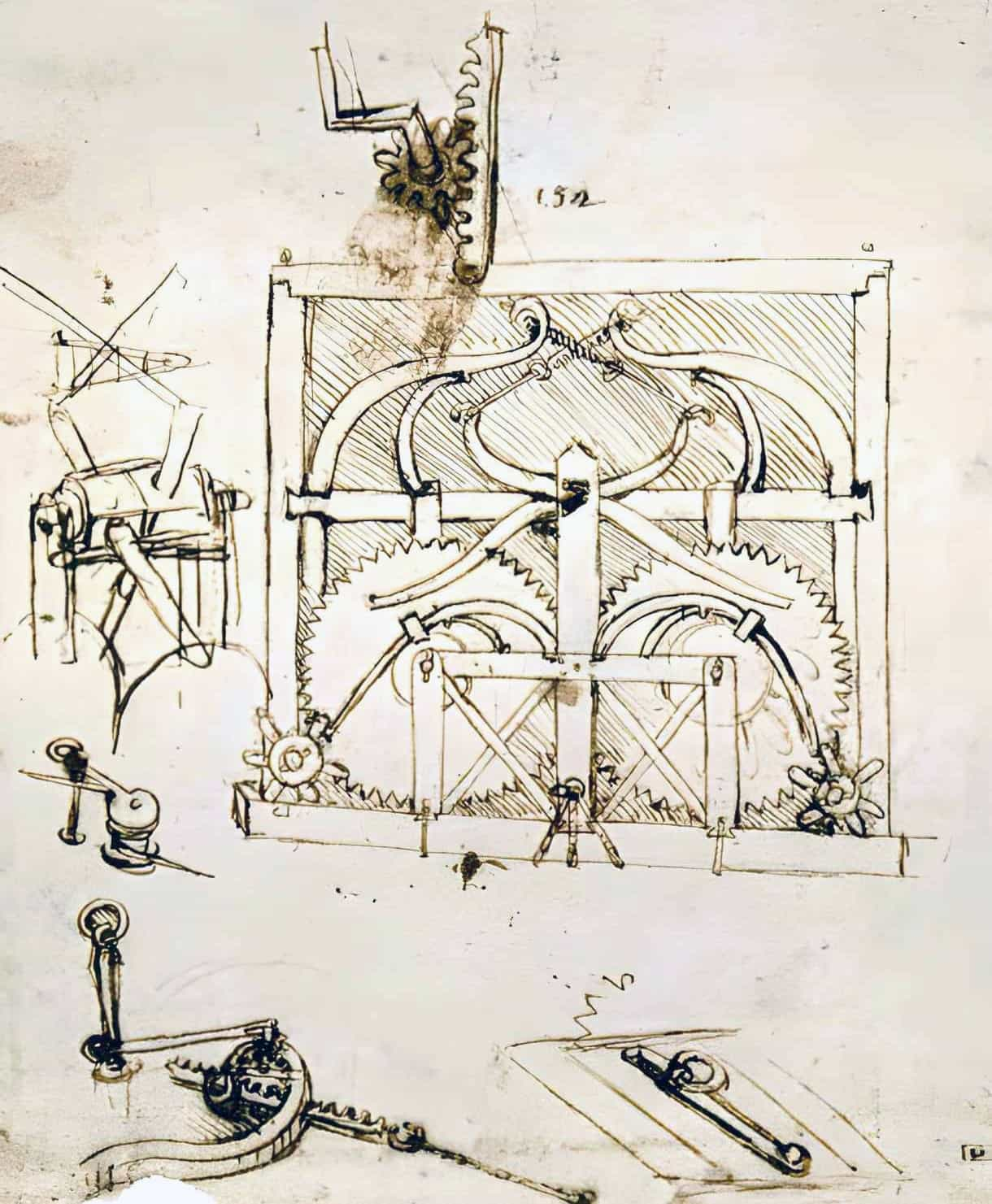

The main features of Leonardo’s automaton can be gathered from the many sketches of it that were preserved in the Codex Atlanticus. Leonardo’s goal was to create a machine capable of moving, so he gave it a complex system of toothed wheels that were set in motion by a pair of springs that could store and release energy at will.

Since the springs lost their power quite fast once released, da Vinci had to include a balance wheel, similar to the clocks, to prevent the jerky motion of the wheels.

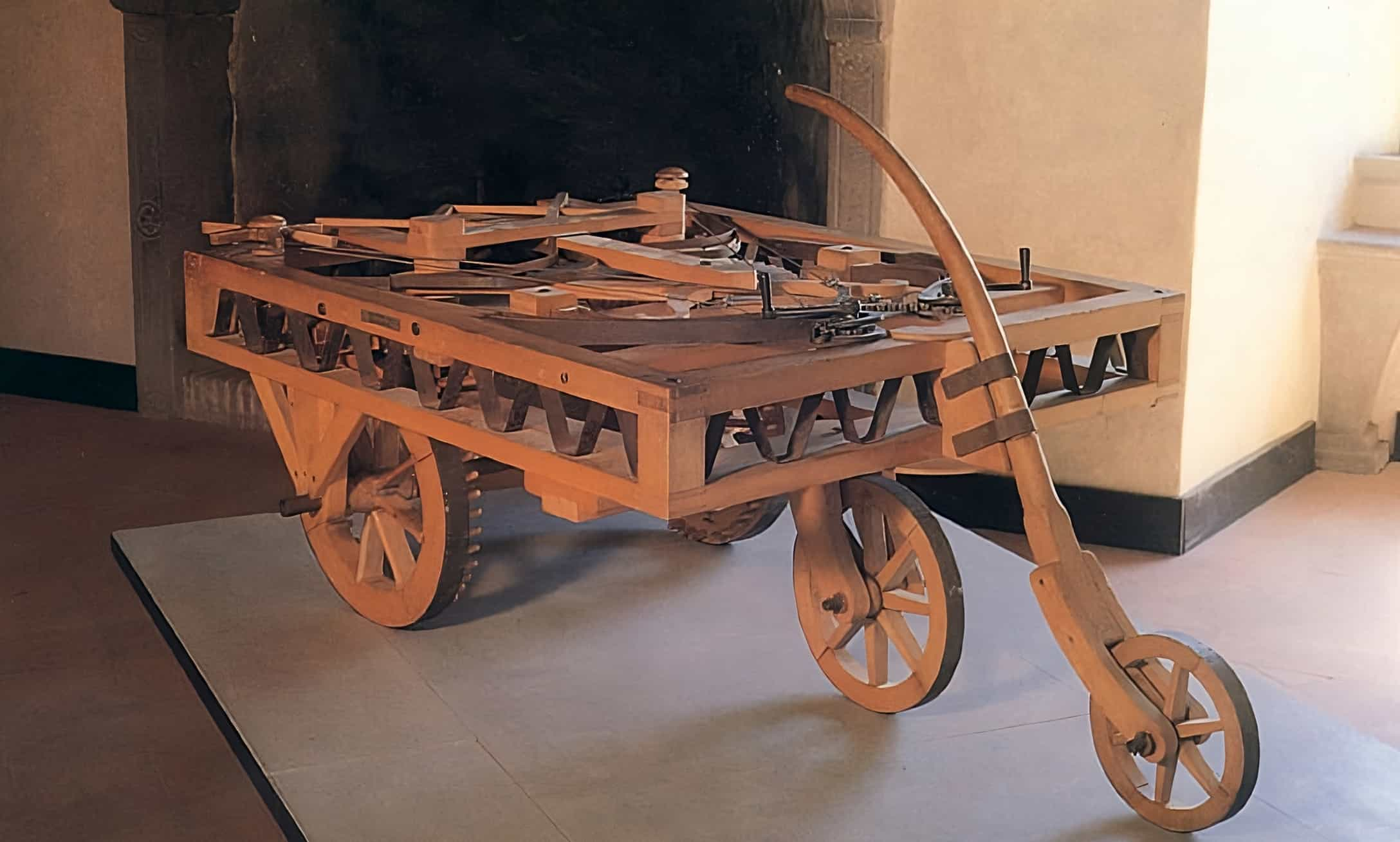

This primitive forerunner to the car was propelled forward and turned on its own by a spring mechanism reminiscent of a clock. But it could only turn right. This self-propelled cart was mainly composed of wood.

By examining the drawings, we can see that Leonardo installed a crude differential in the cart so that the turning angle of the automata could be set beforehand. In other words, da Vinci’s Self-Propelled Cart had “programmed” steering.

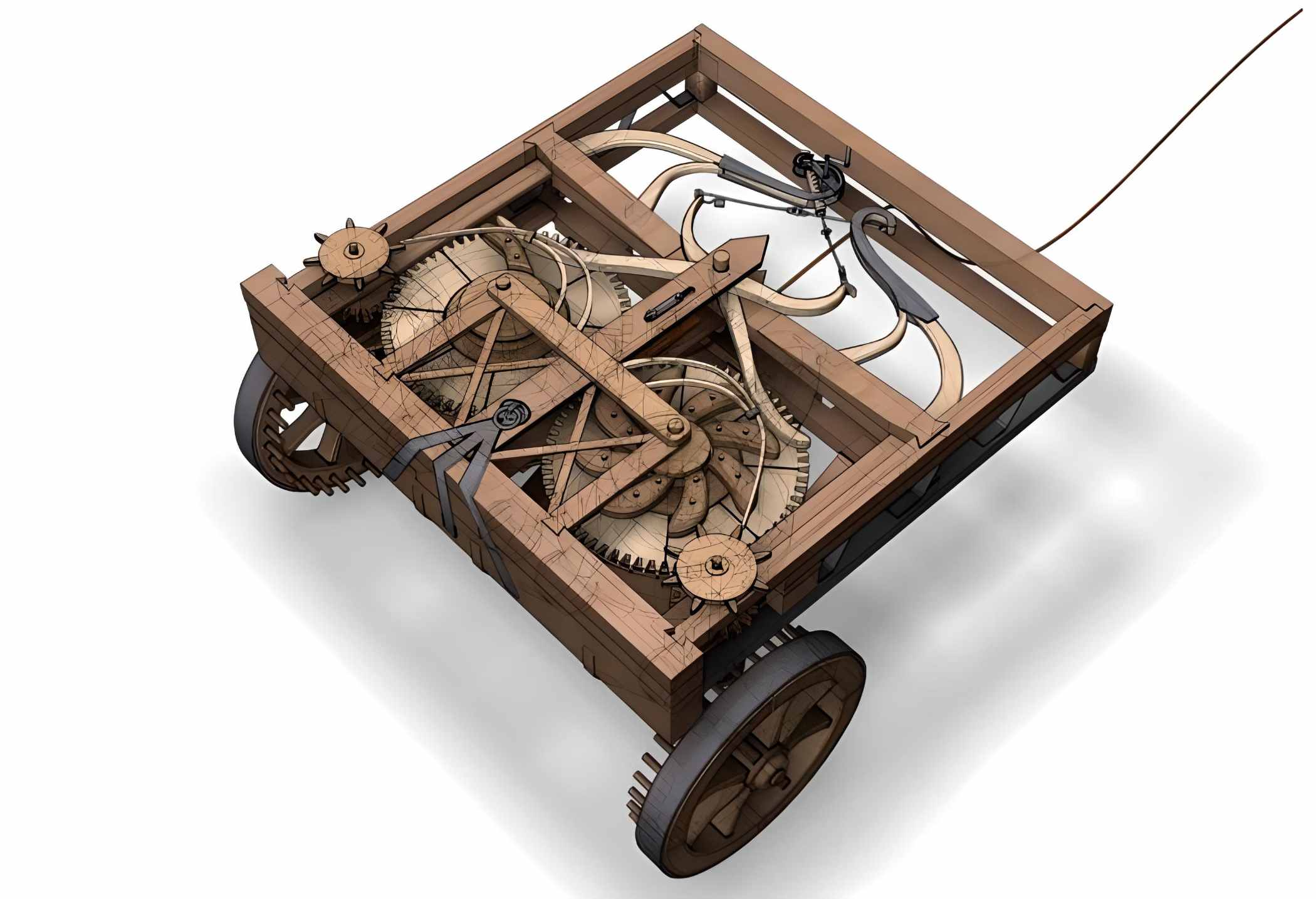

The cart was 5 feet 6.20 inches (1,680 mm) in length and 4 feet 10.75 inches (1,492 mm) in width. The frame and clockwork components, such as cogs, were made of five types of wood.

History of the Self-Propelled Cart

Leonardo da Vinci created this spring-loaded cart prototype around 1478, inspired by the workings of the first mechanical clocks of his day, which were roughly invented in the late 13th century.

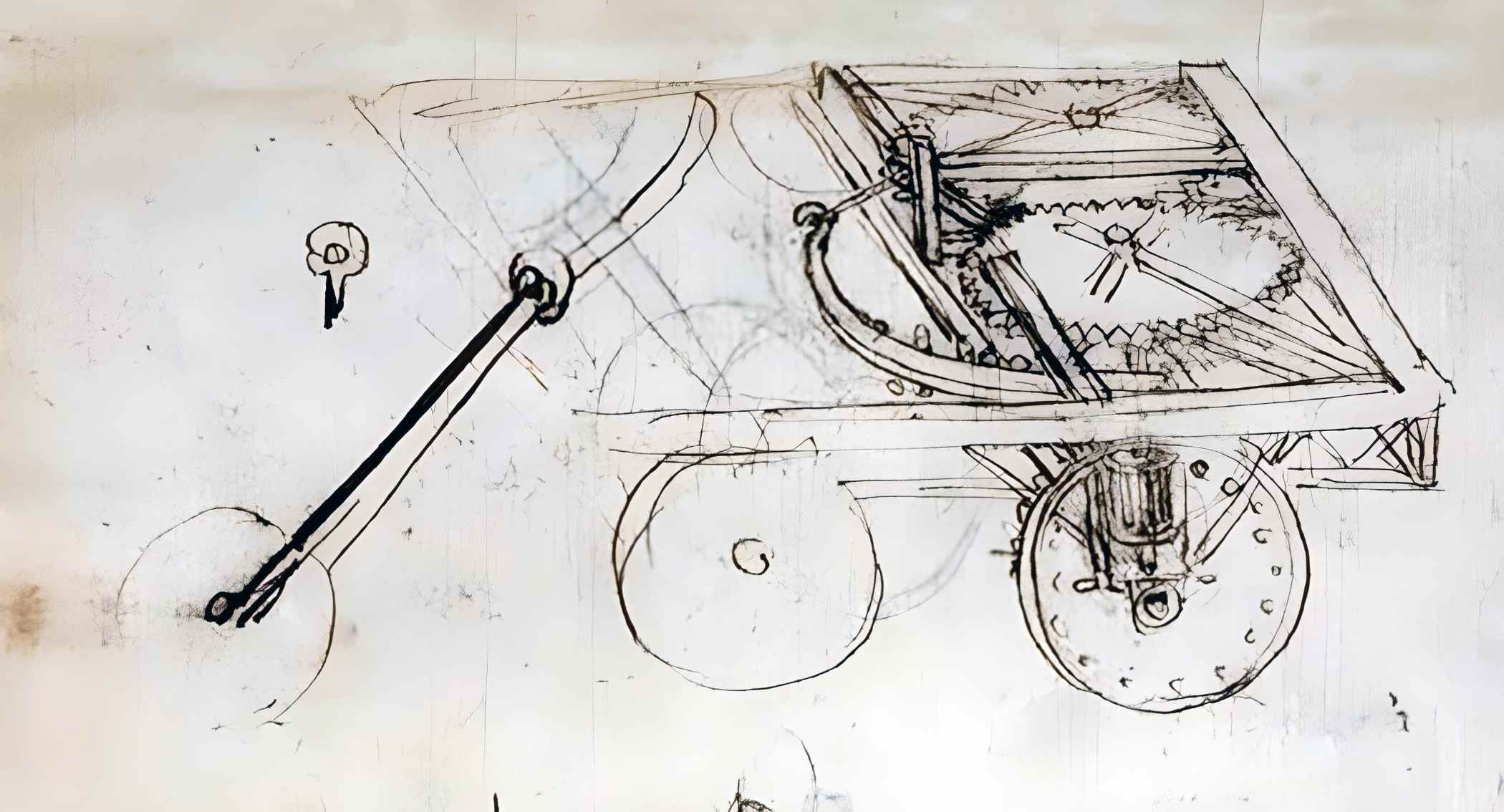

In his Codex Atlanticus, he included a short, uncommented schematic of a chassis-motor arrangement without a body, but this is all that is left of it today.

The three-wheeled cart was only one of Da Vinci’s many transportation designs that made use of gears for propulsion and movement.

The Italian scientist used the complex arrangement of gear teeth in several of his inventions, such as lens sharpening and metal-rounding devices, indicating a profound theoretical grasp of the operation of gears.

Leonardo did not plan widespread usage for his invention. It couldn’t be called a real automobile either since there was no passenger seat. The vehicle was created with the purpose of being breathtaking and attractive for Renaissance fairs.

But the car remained only on paper. There might be a number of explanations for this; Leonardo either lacked the resources to build the vehicle, or the officials thought that it was too dangerous to operate.

How Did Leonardo’s Self-Propelled Cart Work?

When Leonardo da Vinci invented his self-propelled cart, he was also working on early clocks, studying perpetual motion, and many other aspects of mechanical engineering.

The cart has a simple differential and is driven by two independent wheels. Its mechanical assembly consists of a gear, rack, cogwheel, and pinion.

The body was equipped with gears, a steering mechanism, and a brake. The steering was actually “programmed” by inserting wooden blocks between the gears at certain levels.

The whole design was made of gears and springs. The turning angle was changeable using a differential-like system; however, it was impossible for the car to make a left turn.

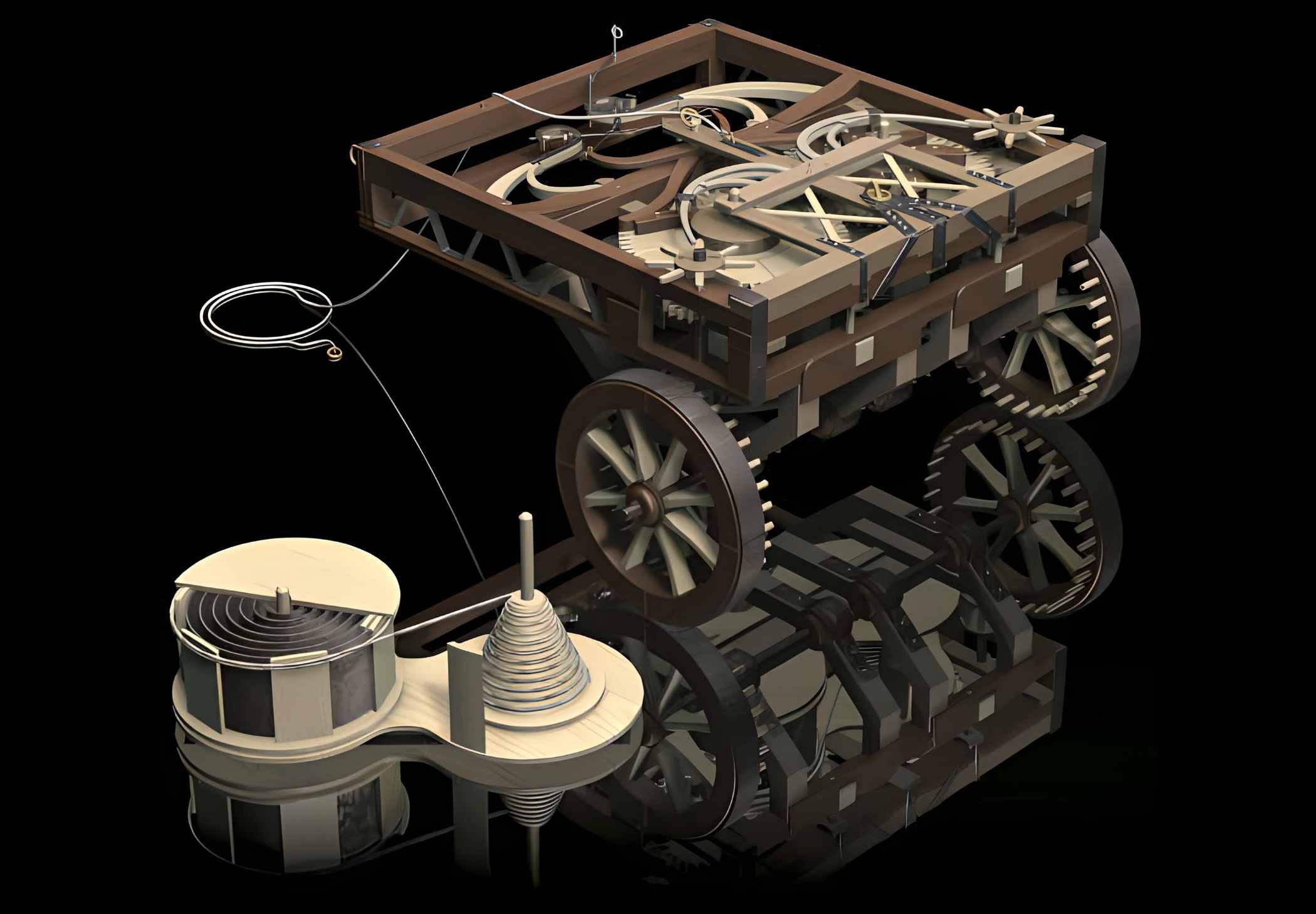

The whole machine seems to be propelled and controlled by a complicated system of gears and escapement inspired by watchmaking. Although the mechanism is based on two symmetrical leaf springs (the type of spring used in car suspensions), one spring was actually sufficient.

Leonardo Da Vinci designed his automobile in such a way that it was also possible to maneuver the tricycle by using the third wheel as a rudder.

Since Leonardo da Vinci’s research in 1490 led him to the conclusion that the notion of perpetual motion was dynamically impossible, he did not intend to build a machine that could run on its own power without any external input of energy.

When it came to traveling from one place to another, Leonardo was a prolific inventor. But historians have concluded that da Vinci intended his cart only for show purposes.

Replica of the Self-Propelled Cart

Leonardo da Vinci conceptualized the mostly wooden vehicle in 1478. The Codex Atlanticus details the workings of this spring car, but the drawings are uncommented, which leaves historians and technologists scratching their heads. Italian historian Carlo Pedretti found out that a misunderstanding prevented the replica from becoming a reality.

Specifically, the vehicle was propelled by two helical springs housed in two cylinders located underneath it. These larger springs in cylindrical tambours powered the cart.

But for a long time, it was assumed that the other leaf springs, the ones that were more visible in the designs, played this function. By rotating the wheels in reverse, the springs were wound up, propelling the cart forward.

Pedretti built da Vinci’s automobile using techniques and technology accessible during da Vinci’s lifetime, beginning with a computerized model constructed with the assistance of American robotics expert Mark Rosheim. The most challenging part was finding a suitable wood for the gears, which needed to be both robust and durable.

A group of scientists from Florence, Italy’s Galileo Museum created a functional replica of da Vinci’s unfinished self-propelled cart in 2004. The two enormous gears in the prototype are driven separately by a double mainspring. This double mainspring was developed about the same time as the first spring clocks in the early 15th century.

This piece of design is not shown in the original drawing but was essential to its operation and it allowed the vehicle to move across a distance of approximately 131 feet (40 meters) once the break was released.

A system of upper leaf springs, again borrowed from the clock industry, allowed for precise manipulation of the speeds of the two independent wheels, and provided precise control over both speed and direction.

Near the Château d’Amboise, where Leonardo, a guest of Francis I of France, spent the final years of his life, lies the Château de Clos-Lucé, which has a museum that maintains several of Leonardo’s replica inventions, including a reproduction of da Vinci’s Self-Propelled Cart.

The self-propelled cart was recreated again on May 11, 2009, on the Discovery Channel show Doing Da Vinci.

The Museums That Display da Vinci’s Self-Propelled Cart

- Museo Nazionale dell’Automobile (Florence, Italy)

- Museo Galileo (Florence, Italy)

- Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci (Milan, Italy)

- Museo leonardiano di Vinci (Florence, Italy)

- Clos Lucé (Amboise, France)