In Hawaiian mythology, Lono is the deity associated with fertility and music, descending to Earth on a rainbow to marry Laka. In agricultural traditions, Lono is linked to rain and agricultural produce. He was one of the four pre-existing gods (along with Kū, Kāne, and his twin brother Kanaloa) before the creation of the world. Lono was also revered as the god of peace, and an annual grand festival called Makahiki was dedicated to him. During this period, from October to February, all unnecessary combat or tasks were considered kapu.

The Legend of Lono

The god Lono and his wahine (wife), Kaikilania-liiopuna, lived beneath a cliff in Kealakekua. One day, Lono overheard a man talking to Kaikilania-liiopuna about running away together. Filled with rage, Lono killed Kaikilania-liiopuna and carried her to the temple. After leaving Kaikilania-liiopuna’s body in the temple, he traveled through the islands of Hawaii, Maui, Molokai, Oahu, and Kauai, engaging in fights with anyone who crossed his path, claiming to be mad with love. Later, he departed on a paimalu (triangular canoe) for foreign lands. Kaikilania-liiopuna returned to life and set out in search of Lono in foreign lands.

-> See also: Christmas in Hawaii: Traditions, Celebrations, and History

The Celebration of Lono

The Makahiki celebration is dedicated to the god Lono. It most often occurs annually at the end of October or early November and lasts for four months, starting on the first full moon after the appearance of the Pleiades stars (a star cluster in Taurus). In times past, when the period of celebrations for Lono arrived, the kahunas (priests) would roam the island dressed in white Kapa, announcing that it was a time of peace and wars were prohibited.

The temples of the god Ku were to be closed during this period. It was a time for the people to rest and celebrate. The kahunas offered prayers to Lono for rain and a good harvest, and ho’okupu (offerings) were collected from the maka’āinana (citizens), which could be products of the land or kino lau (symbols) of Lono. There was a procession through the districts where offerings were accepted, and the plantations were blessed.

Lono and the Death of Captain Cook

Some Hawaiians believed that Captain James Cook was the returning Lono, potentially contributing to Cook’s eventual demise (refer to James Cook’s Third Voyage (1776–1799)). However, it remains unclear whether Cook was mistaken for the god Lono or for one of several historical or legendary figures also referenced as Lono-i-ka-Makahiki.

According to Beckwith, there was a tradition suggesting a human manifestation of the god Lono, who instituted games and perhaps the annual tribute, before departing to “Kahiki,” promising to return “by the sea in the ʻAuwaʻalalua canoes,” as per the gloss. “A Spanish man-of-war” is the queen’s translation, alluding to the tradition of a Spanish galleon straying off course in the early Pacific exploration; Pukui provides a more literal translation for ʻAu[hau]-waʻa-l[o]a-lua, “a huge double canoe.” Keawe’s son, born during the Makahiki, was named Lono-i-ka-Makahiki by his mother, possibly considering the child a symbol of the god’s promised return (Beckwith 1951).

“There is another earlier Lono-i-ka-makahiki, from the ʻUmi line of ruling chiefs of Hawaiʻi, more renowned in Hawaiian legendary history. This Lono was born and raised not far from where Keawe’s remains and those of his descendants were interwoven in a kind of basket with their ancestors since the times of Liloa, near the site of Captain Cook’s tomb. The tomb is a monument to a brave but excessively despotic visitor from an aristocratic race like the Polynesians. This Lono cultivated the arts of war and word, was famed for dodging arrows and was skilled in riddles. He may have also contributed to the skill contests held during the Makahiki ceremony” (Beckwith 1951).

However, it is unlikely that any of these late rulers from the ʻUmi line were the Lono, whose departure was commemorated in the Makahiki festival, eagerly anticipated by the priests of the Lono cult in Hawai’i. Both were born in Hawai’i, and their legends make no mention of a promise to return. A more plausible candidate for the divine personification is the legendary Laʻa-mai-Kahiki, “The Sacred One from Tahiti,” who belongs to a period several hundred years earlier, before relations were severed with southern groups. Laʻa arrived as a younger member of the Moikeha family from northern Tahiti, some of whose elder members had already settled within the Hawaiian group. He brought with him the small drum and flute used in the hula dance.

The Legacy of Lono

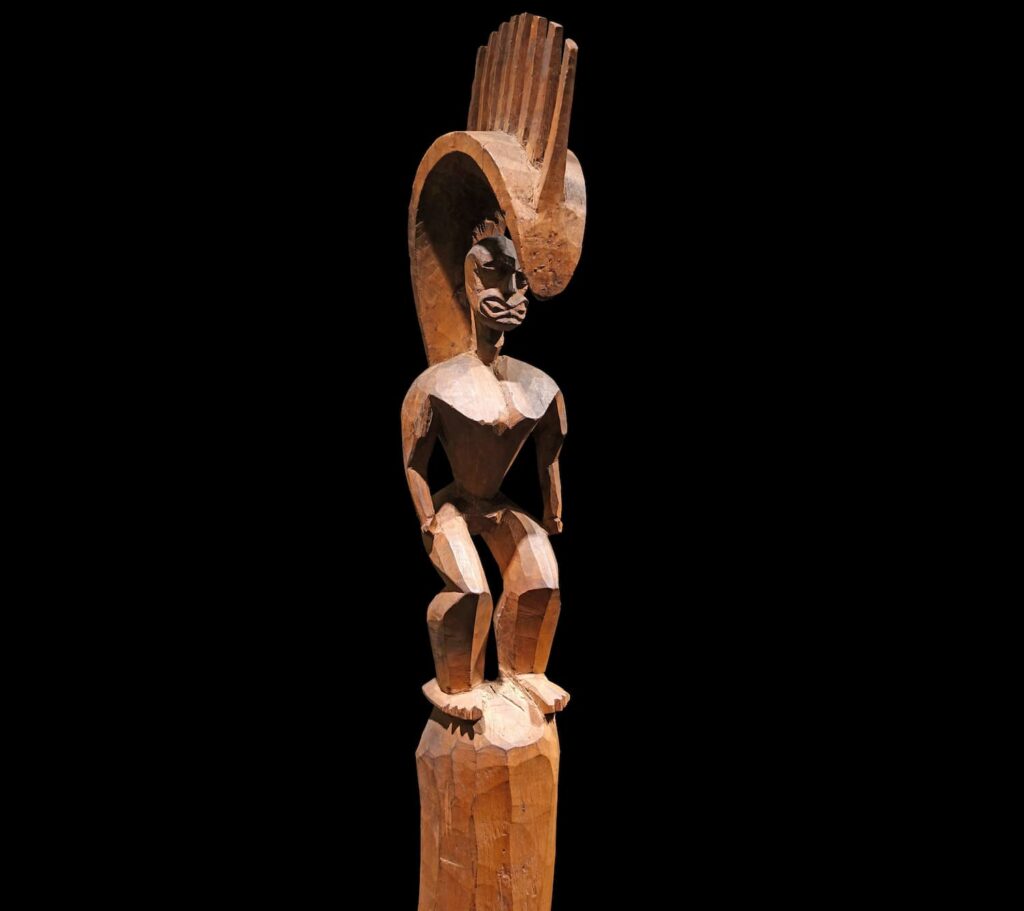

As his canoe passed along the coast, people heard the sound of the flute and the rhythm of the new drum, exclaiming, “It is the god Kupulupulu!” and presenting offerings. Kupulupulu is Laka, revered as the hula god in the form of the blooming lehua tree and also embraced as the god of fertility for wild plants, which sustained the early settlers and continued to some extent during the cold winter months before the harvest of staple foods. This Laʻa-mai-kahiki took wives in various districts, notably in Oahu, a stronghold of the Lono cult, claimed by some present-day families as their ancestry.

It appears he returned to Tahiti at least once before his final departure. The stay of this traveler, from a large family from the south who arrived as a god, enriched the New Year festival with games and performances, likely establishing the collection of tributes following the southern model. His departure left behind a legend of divine personification, suggesting a much earlier appearance of the Lono of the Makahiki, in whose name the Kumulipo chant was dedicated to the infant heir of Keawe (Beckwith 1951).

The Story of James Cook and Lono

Captain James Cook served as the commander of the HMS Resolution and Discovery, which explored the Hawaiian Islands between 1778 and 1779. Cook anchored in Kealakekua Bay on the western side of Hawaii during the natives’ Makahiki celebration in December 1778. Hawaiians believed Cook to be their god Lono, as there was a belief that Lono would return to Kahiki and celebrate Makahiki with them. The natives welcomed Cook with offerings such as pigs, coconuts, rare feathers, and red kapa cloth. Priest Koa received him, and the natives revered him, dancing and singing.

During Cook and his sailors’ stay in Kealakekua Bay, non-divine behaviors and events were observed by the natives, such as on February 1, 1779. On this day, due to the need for firewood, Cook proposed to Koa to purchase wood from a fallen fence near the temple. Koa offered it for free. When Cook’s sailors went to get the wood, they stole sacred idols from the temple, made of wood, and burned them in the fire as firewood. Another event was the death of William Watman from the HMS Resolution, caused by a stroke.

For Hawaiians, gods were considered immortal. Shortly after Watman’s death, Cook left Kealakekua Bay but had to return due to a broken mast. The natives did not accept them back, and the sailors reacted by shooting and stealing Pa’alea’s canoe, a minor leader in the village. The natives responded by throwing stones, but Pa’alea intervened, urging calm.

During the night, Pa’alea went to the ship and stole a boat in retaliation. Upon learning of the theft, Cook decided to bring one of the leaders aboard to convince him to reimburse the damage. A group of sailors went to capture one of the leaders and ended up killing a high-ranking leader. At that moment, Cook was with the village chief, and upon hearing of the leader’s death, the natives killed Captain Cook.