There was a huge crowd waiting to see the mangos. They wanted to reach out and touch them, smell them out. The Beijing Textile Factory came to a halt on that August day in 1968. Hundreds of people filed in silence to the beautifully adorned altar where Mao Zedong had placed his gift. When the employees realized that Mao had really brought them a mango, they bent down before it as a show of their profound gratitude.

They gathered again a few days later. The employees once again formed a queue and waited. This time, a big pot of water was waiting for them upfront, and every one of them got a teaspoon. The liquid could have a hint of mango flavor if you let it linger on your tongue for a while. There was also a whiff of moldiness.

Many Chinese workers grew to associate the free mangos that Mao gave them with his dedication to the working class.

Mangos became a symbol of the “Great Chairman’s” righteousness, toured the nation like pop singers, were promoted as products, and were worshiped like relics during the brief but bizarre chapter of Mao Zedong’s deadly Cultural Revolution that started in the summer of 1968. Despite the reality that most of them were only dummies.

A bloody decade of torture and killing

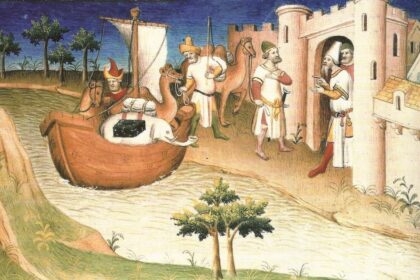

Ten years of mass killing and torture had been unleashed by Mao Zedong’s proclamation of the start of the Chinese Cultural Revolution in 1966. He urged students and schoolchildren to destroy the existing Chinese Communist Party (CCP) structure on purpose so as to build a new one. Using acts of violence against dissidents, traditional cultural places, and religious organizations, the “Red Guards,” as the student groups dubbed themselves, spread “the Red Terror” across China.

The country was on the verge of civil war as “Red Guards” fought violent power battles with one another. Mao was unable to bring them together, so in the summer of 1968, he dissolved the “Red Guards” and established workers’ propaganda squads to carry out the Cultural Revolution in their stead.

When the members of the workers’ and peasants’ propaganda squad took back control of the Tsinghua University from the Red Guards in 1968. Mao rewarded them with 40 mangos.

In an effort to remove the Red Guards from Beijing’s illustrious Tsinghua University, he sent 30,000 manufacturing employees there on July 27. With spears and sulfuric acid, they fought back, killing five and injuring 731. The Red Guards were eventually overwhelmed and surrendered because of the large number of employees.

On August 4, 1968, the foreign minister of Pakistan, Mian Arshad, presented a box of mangos to Mao Zedong during a meeting. Mao decided to reward the worker soldiers at Tsinghua University by presenting them with 40 mango fruits.

Funding for psychedelic fruit consumption

Only a small percentage of Chinese people were familiar with mangos. Wang Xiaoping, a contemporaneous witness, spoke about the fruit in 2013: “A few who were very well informed stated it was an extraordinarily rare and valuable fruit, like the mushroom of immortality, […] yet no one had the least notion what this fruit looked like.”

The reception of Mao’s gift was just as enthusiastic. The official party publication Renmin Ribao reported about the euphoria in Beijing on August 7, 1968.

Even though they were typically only wax dummies, mangos transported by special train to the provinces were sometimes anticipated by hundreds of thousands of people.

Almost immediately, a crowd formed around the attendees. They yelled and sang with unbridled fervor. Their eyes welled up with tears, and they prayed over and again that the Great Leader and Chairman Mao may have a long and healthy life. To disseminate the good news, they assembled work brigades and planned a variety of celebrations to last all night.

The propaganda coup was successful since the mangos were sent from the university to all the factories whose employees had participated in the July 27 coup. They saw the mangos as a sign of Mao’s approval and the end of the “Red Terror.” They were literally able to get their propaganda message out to the populace because of this.

To ridicule a mango is to face the death sentence

Mao’s personal physician, Li Zhisui, said in his 1994 memoirs that when the arrival of the mango was celebrated at the Beijing Textile Factory, “the fruit was sealed in wax, hoping to preserve it for posterity.” Unfortunately, the decaying mango became immediately apparent. As a practical matter, the Revolutionary Committee decided to boil the spoiled fruit in a huge vat. Next, “each worker drank a teaspoon of the water in which the holy mango had been cooked,” as Li puts it.

Li claims that when Mao found out about the workers’ reverence, “he began laughing.” When seen in the context of Mao’s political career, this looks callous now, because just a few years earlier, he had precipitated a famine (the Great Chinese Famine) with the “Great Leap Forward” campaign that killed millions of Chinese and pushed others to cannibalism.

During the height of the Mao Zedong personality cult, buttons bearing images of the “Great Chairman” were widely distributed. From 1966 to 1971, China reportedly manufactured between 2.5 and 5 billion units.

Mangos were responsible for Mao’s rise to prominence in 1968, and he was eventually worshipped for them. Many manufacturers used formaldehyde to preserve their mangos, which were supplied by hospitals. During an interview in February 2016, Zhang Kui revealed that wax mangos, each with its own glass shrine, were created to give to each worker. Numerous fake mangos ended up in Chinese homes by the thousands.

Although many places of worship were demolished during the Cultural Revolution, a new path was being forged out of a yearning for spirituality. According to Li Zhisui, mangos were elevated to the status of holy relics. A warning was given to anyone who handled the waxed mango shrine improperly. According to the Daily Telegraph, in 2013, a dentist from a tiny community was hanged for deliberate disparagement after he compared a mango to a sweet potato.

Mango cigarettes are a hit

Mango mania quickly spread across the nation. Since September, all provinces have been receiving shipments of phony fruit. The mangos were treated like rock stars and sent on a tour on special trains. On September 19th, half a million people waited in Chengdu for one of the wax mangos to arrive, just as they had in other places.

The leading manufacturer of machine tools in Beijing even hired a plane to transport a mango to its Shanghai counterpart factory. The automobile that transported the fruit to the airport was followed by a crowd of observers and drummers. In Guizhou province, hundreds of armed peasants battled to the death over a black-and-white photocopy of a mango.

The Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda department capitalized on the increasing popularity of mangoes by creating a wide range of mango-themed goods.

The CCP’s propaganda machine benefited from the global mango frenzy. It mass-produced items including mango-patterned enamelware and washbowls, mango-inspired brooches and dressing tables, and mango-scented soap. There was a market for everything from mango cigarettes to mango-themed bedding. In addition, huge papier-mache mangos were wheeled through the streets on October 1 as part of the national holiday parade.

In little over a year and a half, the popularity of the mango cult began to decline. The disillusionment with the prospect of a world free of fear may have been a contributing factor. There was probably nothing more to it than mangos simply losing their exotic allure. Some employees even found a new use for the waxed mangos by turning them into candles.

A mango movie in 1976

The ailing Chairman Mao, now in his dotage, made fewer public appearances as his health deteriorated. An effort to resurrect the mango cult in 1974 failed when Imelda Marcos, the wife of the Philippine dictator, delivered a box of mangos on a state visit to Mao, who was already wildly ill. Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, had previously supplied fruit to the Chinese laborers and did so again. The expected excitement, however, never materialized; the mango’s formerly potent symbolic significance had long ago worn off.

Jiang made one last effort. She financed the 1975 film The Song of the Mango, about twins who join opposing “Red Guards” at the height of the mango craze. They came to terms with the fact that they must still acknowledge the proletariat’s authority, and, as a result, they welcomed the arrival of mangos with a joyous procession through Beijing’s streets.

As a member of the influential “Gang of Four,” Jiang was detained by the Communist Party’s left-wing within a week of the film’s 1976 debut, and all copies of the mango film were banned. Unfortunately, Mao did not survive to witness the mango show’s debut. His death occurred in Beijing on September 9, 1976, not much earlier.

Mao’s tomb was the subject of an architectural contest. The idea that the chairman should be buried under a massive concrete mango stood out.