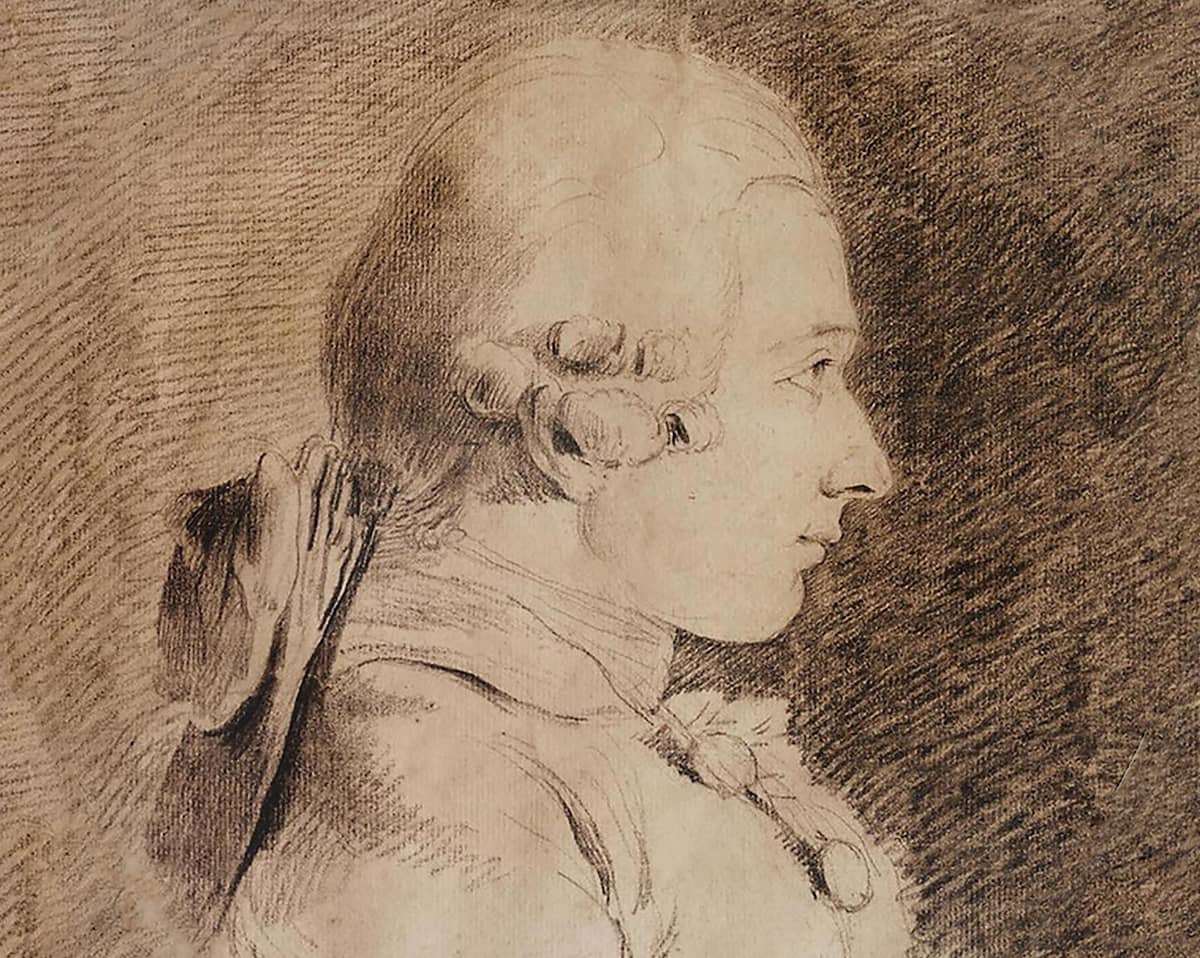

The Marquis de Sade (1740–1814) was a writer and humanist of the Enlightenment era, a great lover of freedom, without taboos and the involvement of God. His work, which is both the theory and the illustration of what will be designated as “sadism,” forms the pathological counterpart of the philosophers and naturalists of his time.

- Origin of the de Sade Family

- The Marquis de Sade: Heir to a Family of Libertines

- A Wedding to Pay Off Debts

- Sade Involved in Dirty Business

- The Marquis de Sade’s Stay in Prison

- Free at Last!

- “Sensible” Muse

- Writing Career

- Theater Stage Manager in Charenton

- The Notoriety and Descendants of the Marquis de Sade

The various regimes that rejected him made him “the most obscure of famous men or the most famous of obscure men.” His name still fascinates and captivates after more than two centuries because he dared to write what no one had ever dared.

—> Sadism, named after the Marquis de Sade, refers to the tendency to derive pleasure from inflicting pain, suffering, or humiliation on others. The term originated from the extreme sexual and violent acts depicted in Sade’s writings.

Origin of the de Sade Family

The de Sade family traces back well before 1177 in the region of Avignon; Laure de Noves, celebrated by Petrarch, married Hugues de Sade in 1325. This merchant family, ennobled by the pope in the 14th century, served the church and the army, thus increasing lands and lordships in the Luberon with Saumane and the magnificent castle of La Coste. While a branch known as “the Sade of Eyguières” produced a high-ranking naval officer during the American War of Independence, the Marquis comes from the branch known as “the Sade of Saumane.”

His grandfather, Gaspard, was Avignon’s ambassador to Pope Clement XI. His father, Jean Baptiste, was the first to leave the region to seek fortune in Paris. Attached to the Bourbons-Condé, he became captain of the dragoons, lieutenant of the provinces of Bresse, and married to a young Countess of Maillé related to Richelieu. Later, as chief counselor and confidant of the Duke of Bourbon, his diplomatic career ended quickly due to libertinism and unfortunate words against Louis XV’s mistress.

A permanent guest of the Hôtel de Condé, he alternated between girls and boys according to his desires but was arrested by the police. He did not understand this punishment since it was his will. He then turned to religion and watched over his son, whom he loved madly, while frequenting salons where he encountered Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Crébillon.

The Marquis de Sade: Heir to a Family of Libertines

Donatien Alphonse François de Sade was born on June 2, 1740, and grew up in the Hôtel de Condé with the future Duke of Bourbon, Prince de Condé, whose grandson would be shot in the moats of Vincennes in 1804, the duke’s brother, the Count of Charolais, a cruel man with peasants and servants, as well as the sister, Mademoiselle de Charolais, who at the age of fifteen already had many lovers.

At five years old, he was sent to live with his uncle, an abbot and vicar of the Archbishop of Toulouse, who maintained several women in his fiefdom of Saumane in Provence. Playing with the village children, he always asserted himself because he was the son and grandson of the local lords.

At the age of ten, at the Collège Louis Le Grand in Paris, he learned Latin and discovered a passion for the theater. In 1755, like all young nobles, he joined the elite regiment of the Chevau-légers of the king’s guard. He was a top-notch cadet who joined the corps under the command of Louis XVIII.

During the Seven Years’ War, he was a captain, conducting himself very well in the army but not in his private life, drawn to gambling tables, brothels, and the theater. Marked in his youth, Donatien was indeed the son and nephew of libertines!

A Wedding to Pay Off Debts

At twenty, he is a libertine; at twenty-three, he indulges in adventures and debts. Marriage with a young lady of the robe nobility, Renée Pélagie Cordier de Montreuil, daughter of the president of the Cour des Aides, is the only solution. The negotiations are tough, as no party wants a libertine and indebted son! Hosted for five years by the Montreuil family and endowed with a dowry of 300,000 livres, they will become the future heirs of castles in Normandy and Burgundy. But the marriage almost didn’t happen: Donatien struggles to leave his good friend in Provence and almost misses the presentation of his future wife at the court.

Married, he resumes his libertine habits, rents an apartment in Versailles, a small house on Rue Mouffetard, as well as another in Arcueil, and indulges in all his pleasures with young girls: sodomy, flagellation, and blasphemy. Louis XV forgives debauchery but not insults to religion: Donatien is arrested barely four months after his marriage, imprisoned in Vincennes while his wife is pregnant, and then exiled to Normandy until his authorization to return to Paris in 1764.

Because of his position as a lieutenant general, he mingles with society, goes out a lot, reunites with his mistresses, and resumes his practices. His father, who died in January 1767, leaves him the castles in Provence, but also the debts and the title of Count that Donatien refuses. He will forever remain Marquis de Sade; only his son Louis Marie, born in August 1767, will carry the title of Count.

Sade Involved in Dirty Business

The Marquis de Sade spent his time between Paris and Provence in the spring of 1768, impregnating his wife, abusing two prostitutes, and whipping a woman who filed a complaint despite receiving 2,500 pounds in compensation. The scandal erupted: 9 months in prison in Saumur, the Conciergerie, and Pierre Encize in Lyon. Released after a trip to Holland, he returned to Paris in the winter of 1769–1770 to discover his son, Claude Armand, born in June 1769. He tried to take care of him but could not resume a military function due to his bad reputation.

He only had time to see his daughter, born in April 1771, before being imprisoned again, this time for gambling debts. To get out of prison in November, he sold his captaincy and left Paris with his entire family for the Château de La Coste, ending his Parisian life. He didn’t mind; he never liked the court; he could live alone in another region. One might think he was calmed, but no, his obsessions would resurface.

In the spring of 1772, the Marquis invited local nobles to his castle for a theatrical performance. Remember, this passion would never leave him; he would write seventeen plays that he signed with DAF, acting as director, stage manager, costume designer, prompter, and actor. He loved to be applauded as an author and actor. In this play, before the nobles, he played alongside a charming young lady (his sister-in-law). Love at first sight happened three years ago. His wife said nothing; she deeply loved her husband.

In June, while he was in Marseille to settle money matters, he had a good time with prostitutes to whom he gave “Richelieu tablets.” These were simple aphrodisiacs, but the girls fell ill and filed complaints. Barely back at the castle, he was warned of his imminent arrest. He fled to nearby Italy with his valet and his young sister-in-law, who was also a canoeist. The scandal was immense!

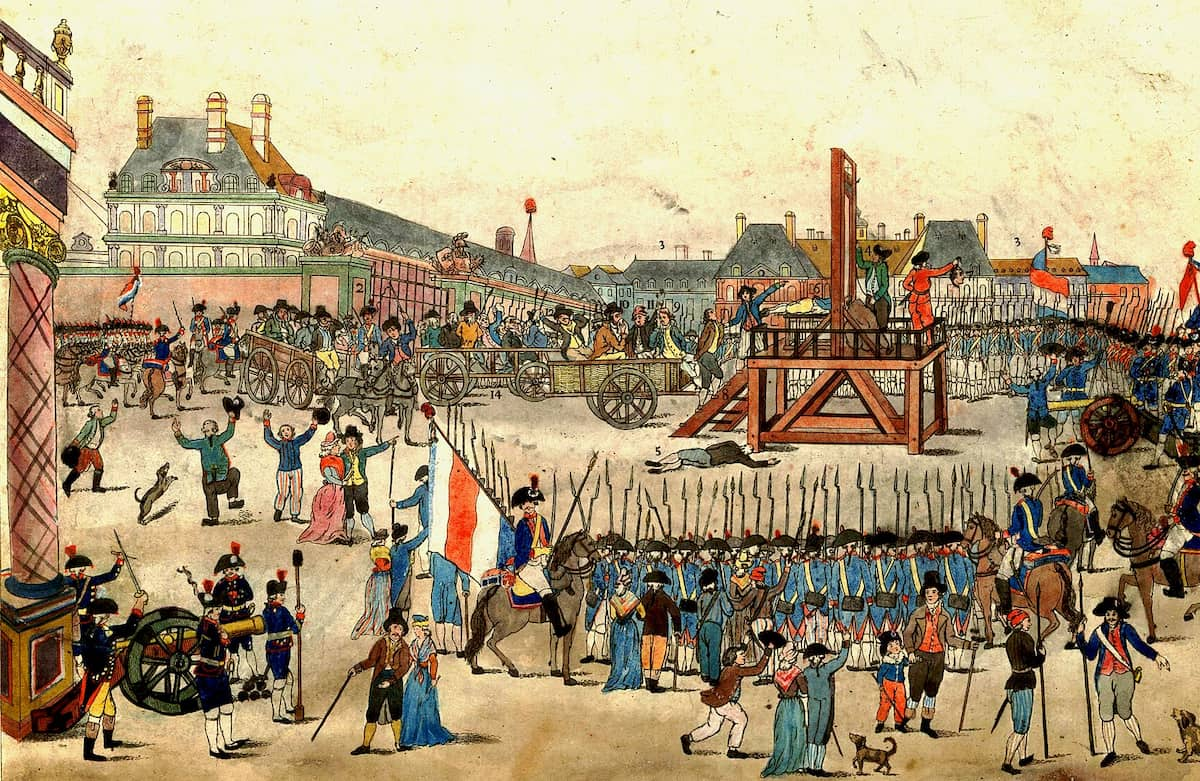

Although his in-laws were outraged, his wife would not stop defending him because in September, the Marquis and his valet were accused of “poisoning and sodomy,” tried, and sentenced to death in absentia, leading to the scaffold where the Marquis was beheaded and his valet hanged, their bodies burned, and their ashes scattered. The girls would recant their confessions, but the damage was done, and dishonor was real.

—>The philosophy of sexuality advocated by the Marquis de Sade emphasized individual freedom and the pursuit of pleasure without moral constraints. He believed in the absolute sovereignty of the individual and rejected conventional notions of sexual morality.

The Marquis and his sister-in-law led a grand life in Italy, but soon their love story came to an end. Sade enjoyed the company of courtesans and could indulge his fantasies, especially after learning that Vivaldi, the great musician, was a priest and a womanizer! The young sister-in-law left him, and Sade and his valet went to Chambéry, then an Italian province, but were arrested in early December 1772 on denunciation by the family. Taken to the Fortress of Miolans, “the Bastille of the Alps,” he was comfortably housed (room, toilet cabinet, table, chamber pot, armchairs, meals delivered, etc.) and could walk around and talk to other prisoners (barons, lieutenants).

His wife tried to join him and devised an escape plan. On April 30, 1773, in the dead of night, three people fled on horseback. The Marquis passed through Bordeaux, then Spain, Cadiz, Zaragoza, Catalonia, and Languedoc, and found himself in Provence by the end of 1773. But confined, afraid to go out, he grew bored… until he left again disguised in Italy. He returned to Lyon in the fall of 1774 to reunite with his wife.

With all her love, she tried to keep him close, but he had a demon in him; he had sex in his blood, and now he was again involved in a dirty affair. The Marquis had just hired a secretary and five young girls whose parents would file complaints of “abduction done without their consent and by seduction.” Rumors spoke of mutilated teenagers hidden at La Coste, money being paid by the Montreuil. But no documents were found; all the pieces of evidence had been destroyed. The Marquis then fled in July 1775 towards Gap, then Florence, under the name of Count de Mazan. First received by Cardinal de Bernis in Rome, he was introduced to Marie Antoinette‘s brother-in-law in Naples in early 1776, who offered him various jobs at the Court.

Back in France, he wrote his “Journey to Italy,” in which he recounted his discovery of castrati, which deeply shocked him; he became studious but still prey to his fantasies, which still got him into trouble. Thinking that in Paris he could go unnoticed, he walked right into the lion’s den! He was arrested in February 1777 and incarcerated in Vincennes. His wife fought so well that she succeeded in having his trial reviewed; he was transferred to Aix-en-Provence in early 1778, and he was retried on the Marseille case.

The judgment was overturned; he was only accused of “admonishment for debauchery and libertinage with a 50-pound fine and a ban from staying in Marseille for three years.” He thought he was free! No! Louis XV’s lettre de cachet was still effective; Louis XVI, horrified by the Marquis’s behavior, would not release him. Under heavy escort, he returned to Paris but managed to escape. Caught again a month later, he was bound, taken to Vincennes, and locked up in September 1778. Thirteen years of detention awaited him, turning him into a completely different man!

The Marquis de Sade’s Stay in Prison

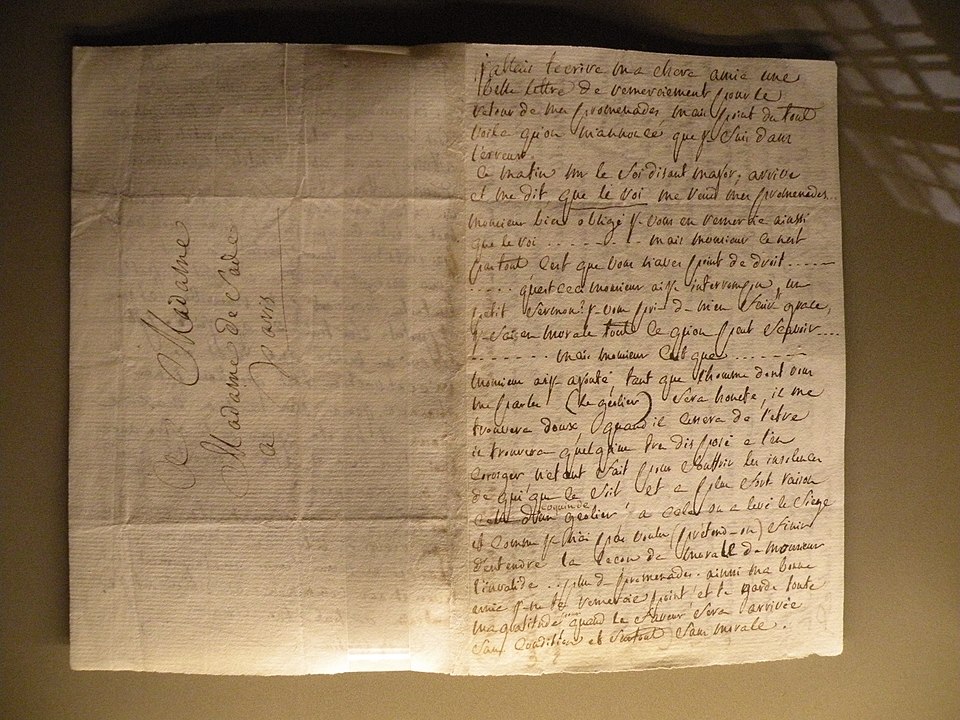

Incarcerated at Vincennes, he spends his time reading (he will have no fewer than 500 books) and indulging in pastries. Nicknamed “Monsieur le 6” because of the number of his cell, he writes many letters proclaiming his innocence or railing against his stepmother, the police lieutenant, or even the governor of the prison. He becomes lucid and realizes that confinement serves little purpose other than degrading the man, embittering him, and making him even more angry.

His wife can finally visit him in July 1781, but he becomes jealous and furious, increasingly aggressive to the point of hitting everyone; she must justify her movements, becoming his scapegoat. Tired of reproaches and exhausted by the blows received, she retires to the convent near the present-day Pantheon, entrusting the children to her mother.

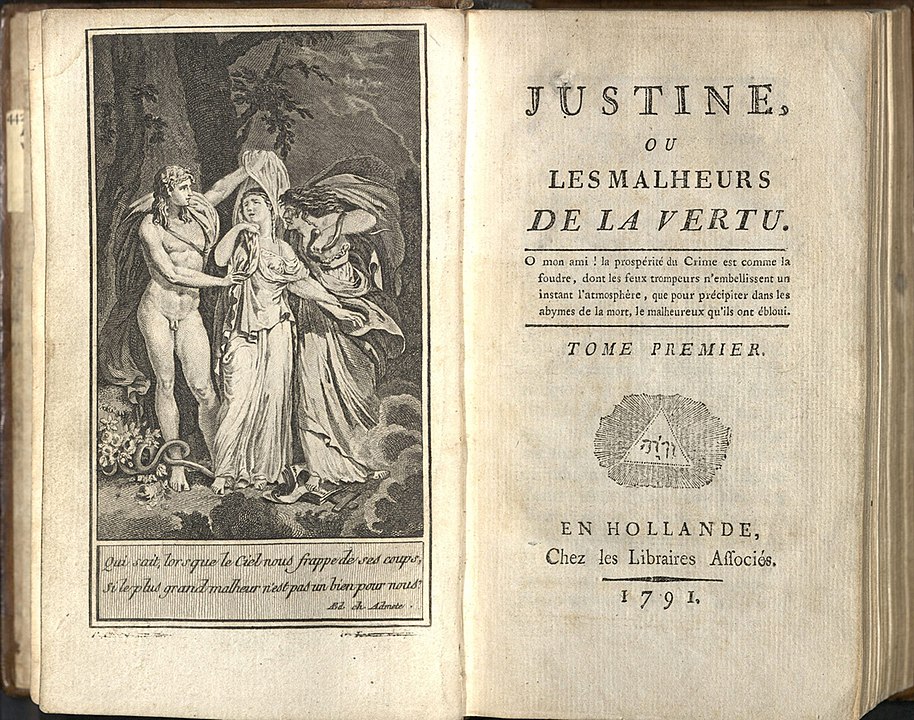

In February 1784, Vincennes closed its doors for lack of occupants. The three remaining nobles are transferred to the Bastille. Installed on the sixth floor of the Tower of Liberty, he can furnish his cell with furniture of his choice and his library of 600 volumes. Gripped by hallucinations and seeing erotic scenes, he begins to write and describe all his repressed desires. This is how “Aline and Valcour” and “Justine or the Misfortunes of Virtue” are written, where one reads, “Everything must be sacrificed for pleasure; it is much less amusing to be virtuous than vicious; vice amuses and virtue tires.”

He can no longer bear the Bastille after five years, but he is unaware of the upheavals in Paris. He screams and calls out to the people; the governor has him evacuated in the middle of the night to the hospital in Charenton, without clothes, without furniture, and especially without his books. It was almost like he regained his freedom because, twelve days later, the people took the Bastille and liberated the prisoners!

In his new prison, he feels lost; all his writings remain at the Bastille. When he learns that the people have taken this prison, he thinks of his masterpiece, “The 120 Days of Sodom,” which was certainly destroyed. Yet this document, passed from hand to hand, sold, and resold, will be published between 1931 and 1935. The original will go from France to Switzerland, to be soon recovered by the BNF and exhibited at the Museum of Letters and Manuscripts! If the Marquis knew…

Free at Last!

According to the will of the Nation, he is free and leaves Charenton with his two sons in April 1790. He is 50 years old, his vision is failing, he has gained weight, and he walks poorly. He wants to see his wife again, who refuses—she who loved him so much during their twenty-seven years of fidelity and who did everything for him. Worse, in June, she requests and obtains a separation of property and goods! His sons prefer Normandy, and his daughter is a nun!

He will not see them again; he does not understand! He finds himself alone, has no friends, and has frequented no circles—only servants and prostitutes. Sade settles near Saint Sulpice and only concerns himself with literature and stage plays, but success is not there; he loses his money. His first book, “Justine or The Misfortunes of Virtue,” published in 1791, is a hit because, as indecent and disgusting as it may be, everyone is clamoring for it: six editions in ten years!

“Sensible” Muse

Having remained alone for so long, he set up a household with a young woman of thirty-three, Marie Constance Quesnet, whom he called “sensible.” They would never separate again. He settled at the current location of the Galeries Lafayette under the name Louis Sade, abandoning the particle and the title of marquis. They would live happily and calmly without intimate relationships, only platonic ones. He himself noted that he had changed: “All of that disgusts me now, as much as it once inflamed me. Thank God, thinking of something else makes me four times happier.” He is transformed; she has become his muse.

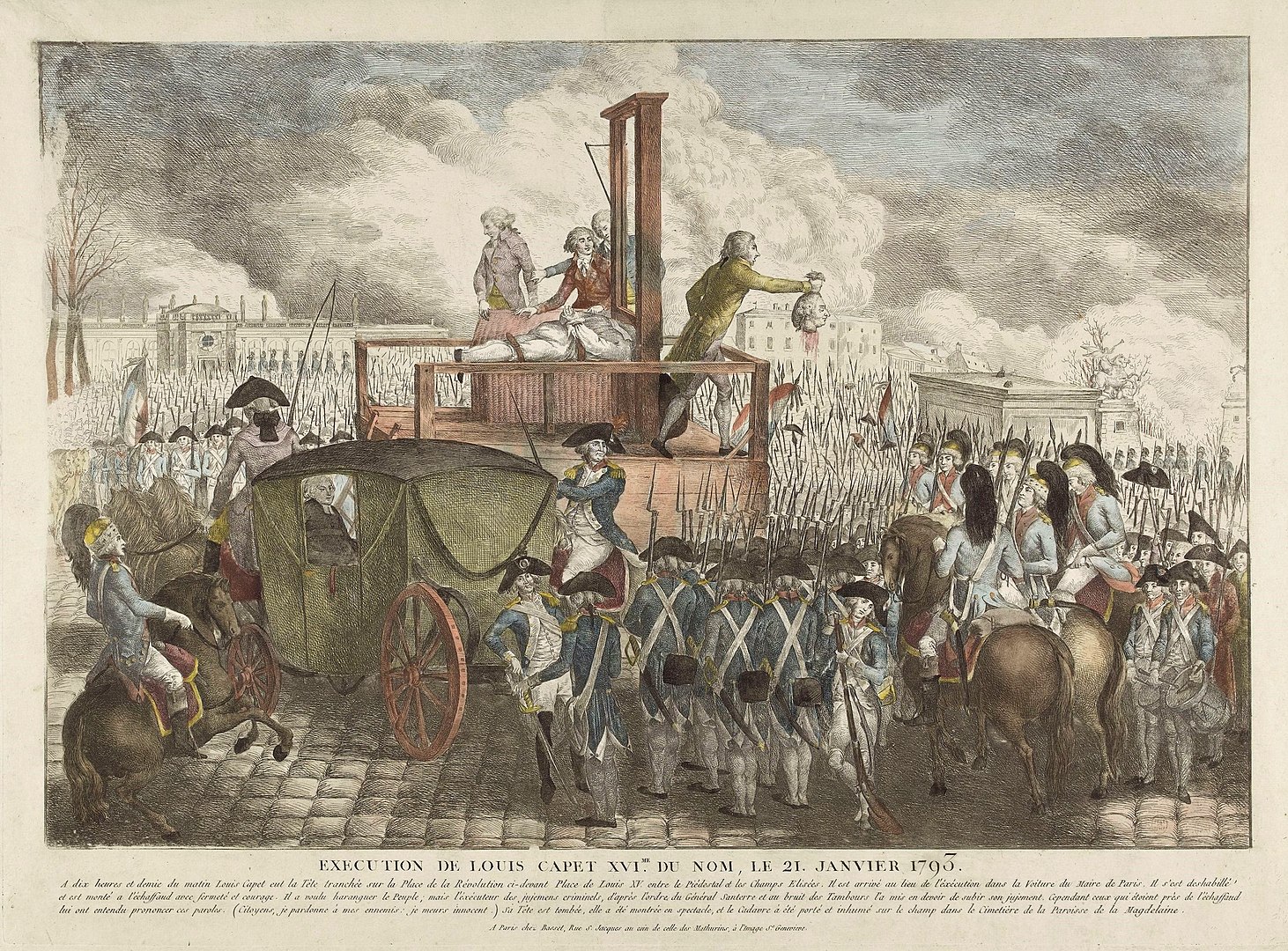

Drawn to the French Revolution while his sons emigrate, he joins the Piques section, attends the Festival of the Federation, and writes a very relevant text for the return of the king from Varennes. Quickly becoming secretary of the section in 1792, he was appointed Commissioner of the Paris sections in the hospitals and thanks to him, the sick were able to benefit from a bed each, whereas previously they slept three to a bed.

Supportive of the democratic evolution of institutions, he is nevertheless against violence like that of August 10 and does not hesitate to write, “The violence of my writings is nothing compared to the current massacres.” Elected Vice President of the Piques section in the spring of 1793, he is happy and satisfied with this official recognition; he does not harm his in-laws who depend on this section, contenting himself with criticizing them, saying, “They are recognized beggars and villains whom I could ruin with a word… but I pity them and I return them contempt and indifference.” He does better; he puts them on a purge list. Sade is moderate, except in religion!

Robespierre, who advocated the institutionalization of the Cult of the Supreme Being, was imprisoned in early December at the Madelonnettes in the Marais. No one helps him; it is the beginning of the Reign of Terror. In January 1794, he was transferred to the Carmes and then to Saint Lazare. He fears being guillotined because the report on his conduct works against him. Sensible is still there, and his friends hide him in Doctor Coignard’s sanatorium, rue de Picpus, “a terrestrial paradise, a beautiful house with a superb garden,” but he is still not reassured.

On July 26, the Revolutionary Tribunal condemns him to death for the second time in absentia for “conspiracy against the Republic.” Curiously, they do not come for him that same day, but only the next day; he has already fled and escaped the guillotine. On July 27, Robespierre is overthrown by the Convention; the Terror ends, Sade is saved, and he is acquitted of all charges in October 1794.

Free, he takes Sensible to Provence, to the Château de La Coste; the property is in ruins, the roof is gone, and the windows and doors are broken and torn down. Disgusted, he sells the castle and some property, then returns to Clichy.

Writing Career

Disgusted, he no longer wants to hear about politics and devotes himself to his career as a man of letters. He published eight volumes of “Aline and Valcour” in 1795 and ten volumes of “La Nouvelle Justine ou les Malheurs de la Vertu” in 1797, which were great successes, but money was still lacking. To survive, he settles in Versailles and accepts a job as a prompter at the city theater. He struggles with the administration to release the sequestration of his property and leases in Provence. To top it all off, he learns of his death on August 29, 1799, through the Gazette! In 1800, he signed “les crimes de l’amour” with his name, written at the Bastille. He thinks he will peacefully finish his life by writing. Well no!

Napoleon Bonaparte calls him a monster; he hates this atheist libertine. In August, the police burned a complete edition of the Nouvelle Justine while preparing his arrest. They took advantage of Sade’s visit to his printer to seize the manuscripts awaiting publication and put him in solitary confinement at the police prefecture in early March 1801.

A month later, he is taken to Sainte-Pélagie, where he will remain for two years. To occupy his time, he creates a literary society with some inmates, but his behavior prompts complaints. Transferred in April 1803 to Bicêtre, “the Bastille of the Scum,” where the worst of the incarcerated are found (rapists, thieves, madmen, murderers), his family finally reacts: okay for the incarceration, but more dignified. He is transferred to the hospice in Charenton; he will never leave there again.

—>Some of the Marquis de Sade’s notable works include “The 120 Days of Sodom,” “Justine,” “Philosophy in the Bedroom,” and “Juliette.” These works explore themes of sexuality, power, and morality in graphic and often disturbing detail.

Theater Stage Manager in Charenton

Charenton, founded in 1641 and placed under the Ministry of the Interior in 1797, served as a type of prison for treating “the insane, dangerous individuals” whose crimes required concealment in the name of official morality. The pension there was substantial, enabling Sade to spend his final years there due to the income from his farms in Provence. As a marquis, he was exempt from the same treatments as the destitute, deemed criminals.

The staff was uncertain about the identity of the “old gentleman dressed in an old-fashioned manner” who spoke eloquently and appeared of noble birth. He freely roamed the park, facilitated by Director Coulmiers, who had almost become his friend; both shared the idea of treating madness through theater. They organized performances monthly, drawing audiences of over 200 people. Additionally, with Coulmiers’ approval, Sensible joined him as early as the summer of 1804.

The performances went smoothly; the actors executed their roles flawlessly, devoid of shouting or bursts of violence. Sade oversaw the staging, conducted rehearsals, and supervised all aspects. The post-performance dinners with the actors and select guests were highly successful. When certain guests learned that the lead actor, a witty and eloquent man, was the Marquis de Sade, they reacted with surprise, fascination, or terror, but never indifference.

Psychoanalysis emerged, yet few comprehended this new form of medicine; many disparaged it, including the newly appointed doctor in 1806, who adamantly rejected these innovations. He petitioned Minister Fouché to relocate Sade elsewhere, citing misconduct and excessive freedom (he particularly disapproved of the post-theater meals and applause). Sade remained unsettled, and searches occurred in June 1807, resulting in the seizure of manuscripts. The Emperor persisted in his interference; Director Coulmiers was dismissed and replaced by someone who prohibited theater performances. It marked the conclusion; Sade sensed it.

On December 2, 1814, the Marquis de Sade passed away shortly before noon. Sensible departed with tears in her eyes but remained at the hospice until her own demise in July 1832. The modest funerals occurred the next day. The Marquis’s remains were interred in the hospice cemetery without a name or date on the slab, contrary to his desire to be buried in Beauce, beneath a copse adorned with acorns, to vanish from this world.

The Notoriety and Descendants of the Marquis de Sade

But the name of the Marquis will never disappear. For about 80 years, it was forgotten and then revived thanks to the Surrealists and painters inspired by him, such as Man Ray, Dali, and Magritte. Paul Eluard wrote, “Three men helped my thoughts to free themselves: the Marquis de Sade, the Count of Lautréamont, and André Breton.” The authors paid homage to him in various ways. Influential figures like Victor Hugo, with his Notre Dame de Paris, Georges Sand, Eugène Sue, Lamartine, and Baudelaire, whose bedside book was “Justine,” were influenced by his writings. Even Simone de Beauvoir acknowledged his impact. Plays were dedicated to him, a Sade Prize was created, films were released, residences regained their splendor, and some became part of the heritage.

The descendants remained discreet, with notable names noted through alliances: Pierre de Chevigné, a resistance fighter, deputy, and Minister of War under the IVth Republic; Henri de Raincourt, president of the General Council of Yonne; Henri de Castries, a classmate of François Hollande at the ENA and CEO of Axa; and Philippes Lannes de Montebello, former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

However, those born between 1947 and 1956 revived his work by saying, “We must dare to speak of Sade; the Marquis is, above all, the symbol of freedom. A free man transcends prisons; a free spirit transcends centuries.”

Ultimately, why has this man made such a mark on minds? Simply put, even though his private life was questionable, he was not discreet; his sexual life was more fantasized about than lived because, during his thirty years of confinement, he had to content himself with writing fantasies instead of fulfilling them. Sade is not rehabilitated; he remains “this eternal Spanish inn, in which everyone finds what they bring, sees what they want to see, and understands what they want to understand.”