For a long time, astronomers have suspected: There must also be intermediate-mass black holes. But reliable observations have not been successful until now. Now, an international research team led by Maximilian Häberle from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg has presented the best evidence yet for exactly such a black hole.

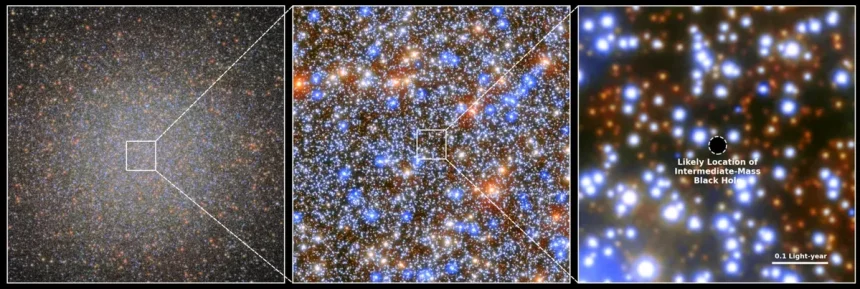

In the archive data of the Hubble Space Telescope, the team detected seven stars moving at extremely high speeds in the center of the globular cluster Omega Centauri. Only the gravitational pull of a black hole could explain the movement of the stars, the researchers write in the journal “Nature.” From their data, they conclude: The black hole at the center of Omega Centauri has 8,200 times the mass of our sun.

The newly described black hole is, considering the vastness of space, close to Earth. It is about 18,000 lightyears away, explains co-author Nadine Neumayer. This makes it the closest known example of a massive black hole. The supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, the Milky Way, is at a distance of about 27,000 lightyears.

Search for Racing Stars

To find new black holes, astronomers had repeatedly searched for such racing stars, unsuccessfully until now. Häberle set out to search again. To calibrate his instruments, he used previously unutilized data from the Hubble telescope, which had repeatedly photographed Omega Centauri. In total, Häberle had access to 500 archive images spanning a period of 20 years. In these images, the researcher meticulously measured the movement of approximately 150,000 stars.

In the end, Häberle not only created the most comprehensive catalog of stellar movements in Omega Centauri to date but also identified seven stars moving at high speeds. At this speed, Häberle believes, the stars should fly out of the star cluster. Only the gravitational pull of a black hole with 8,200 times the solar mass can hold the stars in place, his calculations show.

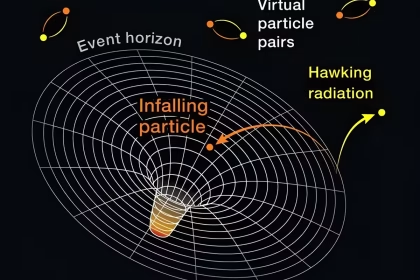

Detecting a black hole with such a mass is of great importance for astronomers. Until now, sky researchers only knew of two types of black holes. So-called stellar black holes with up to 150 solar masses are formed when large stars have exhausted their nuclear energy supply and collapse helplessly.

And then there are the supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies with millions or even billions of times the mass of the sun.

These supermassive black holes are presumed to have formed through the merger of smaller black holes with a few thousand solar masses. Some of those intermediate-mass black holes should still exist in the cosmos today. Indeed, sky researchers have come across a whole series of candidates for such objects in smaller galaxies and globular clusters. But direct evidence was lacking until now: the movement of stars in such distant objects is simply too difficult to observe.

Galaxy Swallowed by the Milky Way

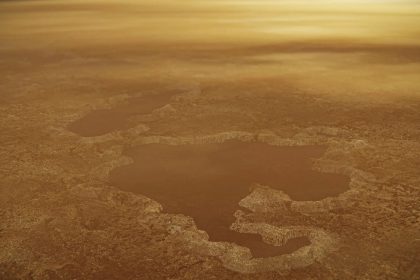

This is where Omega Centauri comes into play: With ten million stars, it is the largest globular cluster in the Milky Way. Even the naked eye can spot it in the southern sky. Omega Centauri is probably the former central region of a small galaxy that collided with the Milky Way billions of years ago, losing its outer regions in the process.

The idea was that if this collision happened, Omega Centauri should still contain an intermediate-mass black hole that was once present in the center of the small galaxy. The globular cluster’s proximity to Earth allows us to observe the movement of stars there.

The stars now detected by Häberle and his team confirm this consideration. However, the Hubble images only show the movement of the stars in the sky and not the movement towards or away from us. The researchers now want to measure the radial movement of the seven racing stars with the James Webb Space Telescope and thus eliminate any last doubts about the existence of the black hole in Omega Centauri.