The Munich Agreement was signed by Germany, France, and the United Kingdom on September 30, 1938. Adolf Hitler had designs on the mostly German Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. Western nations agreed to this in order to avert war with Germany and ensure that Czechoslovakia would not be invaded. The dislocation of Czechoslovakia was sanctioned, and Hitler was able to ascend to power, both of which contributed to the outbreak of World War II as a direct result of these accords.

Why were the Munich agreements signed?

In 1938, Czechoslovakia was a brand-new nation-state founded on the concept of “the right of peoples to self-determination” after the conclusion of World War I. Developed by American president Woodrow Wilson, this principle guarantees that everyone has the freedom to live in and support the kind of state and government that they like. The treaties of Trianon (1920) and Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) established the current boundaries of Czechoslovakia. Various ethnic groups, including Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Ruthenians, Poles, and Germans, made their homes in Czechoslovakia, a country that was founded on the ashes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Trust between these many cultural groupings was precarious. Sudetenland Germans did not appreciate being a part of Czechoslovakia, while Ruthenian and Slovaks sought greater independence. The Germans of the Sudeten region welcomed Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 and sought to join the Third Reich. Hitler said he was acting in the name of the “right of peoples to self-determination” when he annexed the Sudetenland to Germany. A declaration of war against Czechoslovakia’s allies France and the United Kingdom would result from such an annexation. At 1938, Hitler suggested a meeting between himself and the leaders of France and Britain in Munich as a means of resolving the issue. The Munich Agreement was ratified as a result of this meeting.

What was the Sudeten crisis?

There was a region of Czechoslovakia called the Sudetenland, and it was situated in the country’s westernmost region. Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia were all parts of the territory where German was the dominant language. Beginning in the 14th century, Germans settled in that area. The Sudeten Germans were displaced from their homeland after World War I and forced to relocate to the then-new country of Czechoslovakia. A rise in Nazism in the 1930s only served to fortify the already strong sense of nationalism among the Sudeten Germans. The Sudeten German Patriotic Front was founded by Konrad Henlein in 1933; by 1935, it had evolved into the Sudeten German Party. This Nazi-supporting party advocated for annexing Sudetenland. It was no secret that Adolf Hitler wanted to incorporate the neighboring German-speaking territories into the Third Reich, and he did so in pursuit of his pangermanist goals. After the annexation of Austria by the Third Reich in March 1938 (Anschluss), Hitler announced that he would annex the Sudetenland on October 1. In truth, his objective was to attack Czechoslovakia. For France and the United Kingdom, then allies of Czechoslovakia, this was deemed a war provocation. Hitler called the leaders of France and Britain to Munich to negotiate a peace treaty when France was preparing to mobilize its forces.

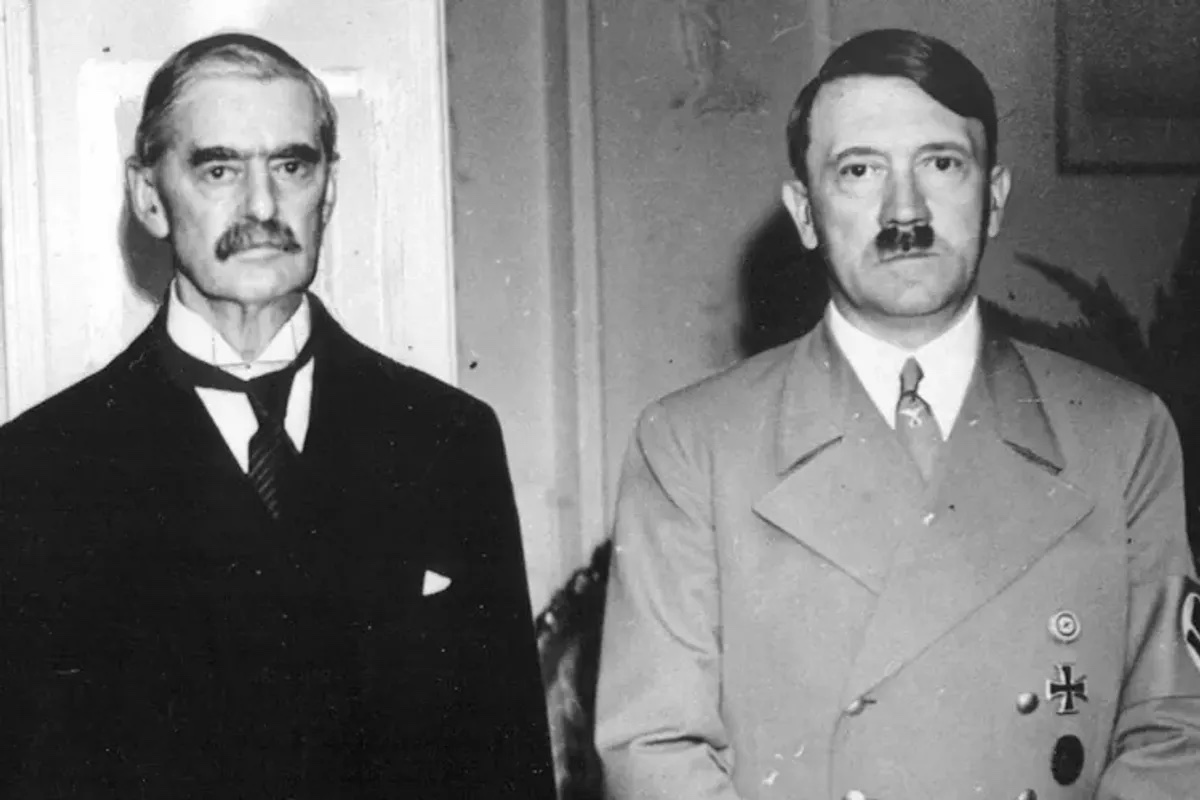

Who signed the Munich Agreement in 1938?

The Munich agreements were signed by :

- Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

- French President Edouard Daladier

- British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

- Fascist Italy’s Benito Mussolini was also there to act as a go-between. Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano was his son-in-law, therefore the two traveled together

President Edvard Benes of Czechoslovakia was not invited to the summit even though its outcomes would have a significant impact on his country’s future. The Soviet Union was ready to support Czechoslovakia militarily, but only if France did the same. In spite of this, both Poland and Romania denied Soviet soldiers access to their countries. Furthermore, France and the United Kingdom did not want Soviet representatives at the summit for fear of upsetting Hitler. A “capitulation” to the Führer was criticized by the Soviet foreign minister.

How did the signing of the Munich Agreement take place?

In 1938, on September 29th, the Munich Conference was held. It took place at Adolf Hitler’s Führerbau, also known as the “Führer’s Building,” in Munich. Benito Mussolini suggested that he and Adolf Hitler meet. Even if Hitler was prepared to go to war, his Italian ally was not. Mussolini sought to prevent war in Europe by means of this summit. France and Britain, for their part, were not eager to go to war with Germany. After the Sudetenland is annexed, Hitler promises, he will not make any more territorial claims and European peace would be secure. On September 30 at 1:30 a.m., the Munich Agreement was ratified. As long as it didn’t attack the rest of Czechoslovakia, Germany was allowed to acquire the Sudetenland area. France and the United Kingdom, anticipating an eventual battle with Germany, have been given a respite by the accords.

How was Czechoslovakia dismantled?

The breakup of Czechoslovakia began with the Munich Agreement. When German forces invaded the Sudetenland on September 30, 1938, an estimated 150,000 to 250,000 Czechs were forced to leave their homes. Almost 5 million people left Czechoslovakia, along with key defensive structures and the country’s entire weapons manufacturing infrastructure. As soon as the dust settled from the accords, Poland moved in to take the mostly Polish territory of Zaolzie. To the south of Slovakia, where Hungarians made up the majority, Hungary did the same thing in November 1938. Hungary conquered Ruthenia on March 15, 1939, when Germany attacked the rest of Czechoslovakia. Following its complete occupation by the Third Reich in March 1939, Czechoslovakia became the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the Slovak Republic.

What were the results of the Munich Agreement?

Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler held parallel peace talks for a future settlement of British and German disagreements alongside the Munich Agreement. When he came back, everyone treated him like a hero and started calling him “the peacemaker.” However, Edouard Daladier was worried that he would be blamed for caving to Hitler’s demands. Popular opinion, relieved to have avoided war, praised him for his efforts to “keep the peace” and applauded his return to France. Leader of the Soviet Union Stalin was dissatisfied with the Munich Accords. His argument was that France had violated a covenant of mutual aid with the Soviet Union by surrendering Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany. He was worried that the Allies would make more deals with Germany to partition the Soviet Union. As a result, in August of 1939, Stalin met with Hitler and inked the German-Soviet alliance. German soldiers invaded Czechoslovakia in March 1939 after being abandoned by Western countries, and then attacked Poland in September 1939, thus starting World War II. On March 21, 1939, Germany set up the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. On March 14, Slovakia proclaimed its independence under Hitler’s leadership. Under Jozef Tiso’s leadership, the so-called Slovak Republic was a client state of Nazi Germany. After World War II, Czechoslovakia joined the Soviet Union and the other communist nations to form the European Union. The nation disintegrated shortly after the collapse of the USSR, splitting into the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

KEY DATES OF THE MUNICH AGREEMENTS

28 October 1918: Proclamation of the First Czechoslovak Republic

On October 28, the Czech and Slovak people declared their independence from Austria and Germany, becoming the first Czechoslovak republic. In the wake of the signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, which effectively ended World War I, Austria-Hungary was split in two, giving rise to the independent states of Czechoslovakia and Slovakia. Initially, the Czech Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk served as president. As early as the first month of its existence, its ethnic variety would spark several nationalist disputes. Later, in 1938, the Germans occupied Czechoslovakia and subsequently annexed it.

The Sudeten Crisis Begins on September 15, 1938

Hitler plans to invade Czechoslovakia when he finishes annexing Austria. To save the Sudeten Germans from Czech “oppression,” he officially cites the “right of peoples to self-determination.” Czechoslovakia readied its armed forces in anticipation of a probable German invasion. Neville Chamberlain, prime minister of the United Kingdom, met with Hitler on September 15, 1938, in an effort to defuse the situation. The Führer reassured him that liberating the Sudeten Germans was his main goal, not the destruction of Czechoslovakia. A continuation of discussions necessitated Chamberlain’s return to Germany on September 24. After the recent crackdown by the Czechs against the Sudeten Germans, Hitler has once again called for the disintegration of Czechoslovakia.

September 30, 1938: Signing of the Munich Treaty

After much negotiation, Adolf Hitler, Neville Chamberlain, and Edouard Daladier sign the Munich Agreement at 1:30 in the morning. In order to avert a war, France and the United Kingdom caved to Hitler’s demands. They gave their consent to the German annexation of the Sudetenland. Upon their return to their respective countries, Chamberlain and Daladier were hailed as heroes for having “saved the peace.” In the eyes of the Czechs, the signature of the Munich Treaty by the French and British constituted a betrayal.

October 5, 1938-Resignation of Czechoslovak President Edvard Benes

The fate of Czechoslovakia, led by Edvard Benes since 1935, was decided at the Munich Conference, although Benes was not asked to attend. France and the United Kingdom vowed to stay neutral in the case of a conflict between Germany and Czechoslovakia to coerce him into accepting the accords. On October 5th, 1938, Edvard Benes resigned and went into exile in the United States and then the United Kingdom, where he established the Czechoslovak government in exile.

March 15, 1939-Germany occupies Bohemia-Moravia

Wehrmacht troops rolled into Bohemia and Moravia in western Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939. To avoid angering Hitler, Czechoslovak President Emil Hácha made the decision not to issue a military command to repel the invasion. The Germans established the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia the next day. Emil Hácha maintained his presidency, while Nazi dictator Konstantin von Neurath ran the Protectorate. Mass arrests of political opponents and persecution of Jews and Roma occurred in the early months of the occupation, marking the beginning of repression.

Bibliography:

- Jesenský, Marcel (2014). The Slovak–Polish Border, 1918–1947. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137449641.

- Kirkpatrick, Ivone (1959). The Inner Circle. Macmillan.

- Thomas, Martin. “France and the Czechoslovak crisis.” Diplomacy and Statecraft 10.23 (1999): 122–159.

- Farnham, Barbara Reardon. Roosevelt and the Munich crisis: A study of political decision-making (Princeton University Press, 2021).

- Kornat, Marek (2012). Polityka zagraniczna Polski 1938–1939. Cztery decyzje Józefa Becka (PDF) (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Oskar.