Each physician in ancient Egypt had a specialty. The Greek historian Herodotus reported from a trip to Egypt:

“Each physician treats one disease, not several; some are physicians for the eyes, others for the head, for teeth, for the abdominal region, for gynecology, or for diseases of uncertain localization.”

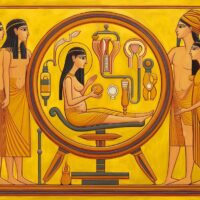

Origin of Obstetrics

Min is the god of fertility. Tauret, a goddess with a hybrid body—part hippopotamus, part crocodile—with lion’s paws, protects the mother and child during childbirth. She is supposed to scare away spirits that could harm the child. She is often accompanied by the dwarf god Bes, who has the same function.

The goddess Hathor, the goddess of maternity and fertility, was called upon to assist the child and the mother, through incantations:

“Place barley and wheat in two linen bags with sand and dates; urinate on them every day; if the barley and wheat germinate, she will give birth; if the barley germinates first, it will be a boy; if the wheat germinates first, it will be a girl; if they do not germinate, she will not give birth.

buy toradol online https://gaetzpharmacy.com/buy-toradol.html no prescription pharmacy

“

In a way, an ancient pregnancy test.

But for medical reasoning to be developed, physicians had to get rid of the idea that pregnancy is due to the intervention of supernatural powers, gods, or demons.

In Egyptian papyri, amid conjuring formulas, mythical conceptions, and superstitions, there is an attempt at rationalization:

- one of the Kahun papyri, dating back to the XII dynasty, is a gynecology manual and mentions a disease that devours tissues (cancer);

- Egyptian physicians had noticed the beneficial action of honey in gynecology;

- in the 14th century, condoms were made with animal bladders as a means of birth control.

To give birth, women squat on four ritual bricks, the Meskhenet, and let midwives proceed with childbirth. The placenta is preserved to make medicinal remedies. Women are then secluded for fourteen days to purify themselves, as they are contaminated with their blood and therefore impure. They will then return to see their child.